Peripheral arterial disease (pAVD) is the manifestation of a disease that is often misjudged in its importance by patients, but also by physicians. Even if the overall prevalence is between 3 and 10%, it is already about 20% in patients >70 years [1]. Initially, it is only mildly symptomatic, yet the pain that occurs with exertion gradually causes a restriction of physical activity – resulting in a reduced quality of life [2]. The prognosis of affected patients is significantly limited by the manifestation of the disease in other organs. Multimodal rehabilitation is the only therapeutic concept that goes beyond the treatment of local symptoms and improves the prognosis of patients in the long term.

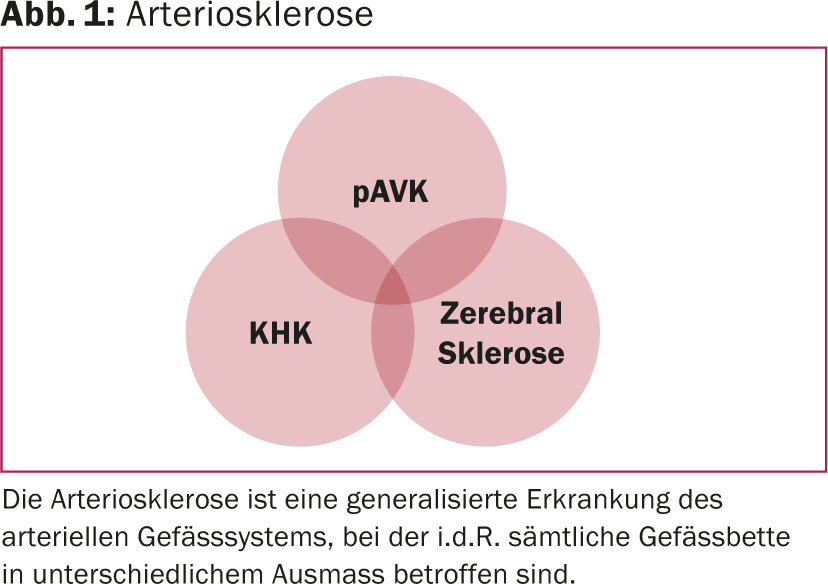

Peripheral arterial disease (pAVD) is the manifestation of systemic vascular disease that can affect all arterial vascular territories equally. In addition to the leg arteries, renal arteries, coronary arteries and brain-supplying arteries are frequently affected. Even if the symptoms of PAOD can be reduced locally with the help of various treatment strategies, the systemic disease still persists – and progresses. The prognosis of affected patients is ultimately largely determined by the manifestation of the disease in other organs: namely, coronary or brain-supplying arteries. The risk of cardiovascular complications is higher in patients with pAVD than after myocardial infarction (Fig. 1).

In the treatment of patients with PAOD, it is therefore particularly important to limit the progression of the underlying disease in addition to the manifest symptoms. Accordingly, the treatment concept comprises two approaches (Fig. 2):

- A local treatment of the pAVK with the aim of freedom from symptoms or extension of the walking distance.

- Treating the underlying disease with the goal of improving mortality by reducing cardiovascular complications. The treatment of vascular risk factors is the most important factor.

Guidelines

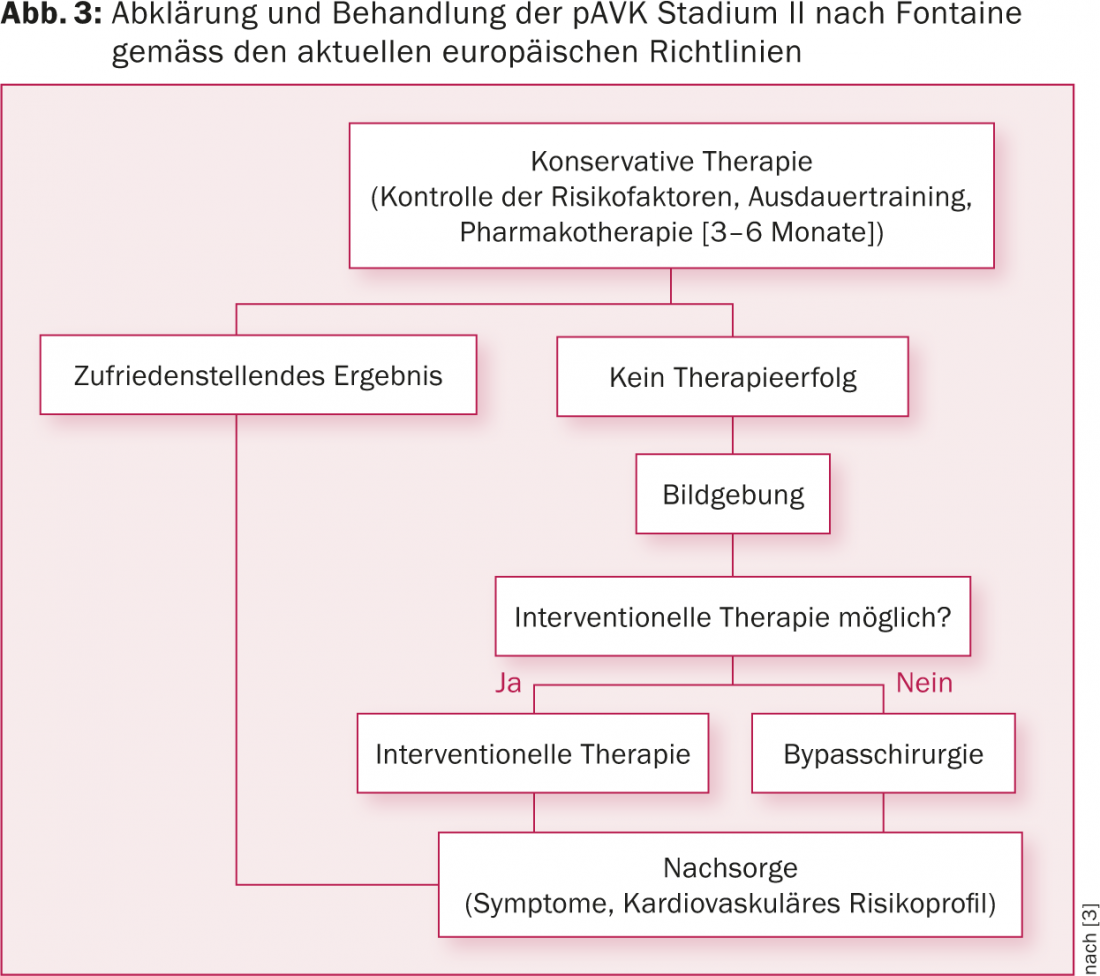

According to current guidelines, a multimodal approach is recommended in patients with PAOD [3]. This includes optimization of vascular risk factors in addition to drug therapy. In asymptomatic pAVK (stage I according to Fontaine) or intermittent claudication (stage II according to Fontaine), a conservative approach can be taken for three to six months. Here, supervised training, as opposed to independent training, is given an IA recommendation [3]. Only if no improvement of the symptoms can be achieved by this, an interventional or surgical procedure is recommended (Fig. 3).

Therapy options

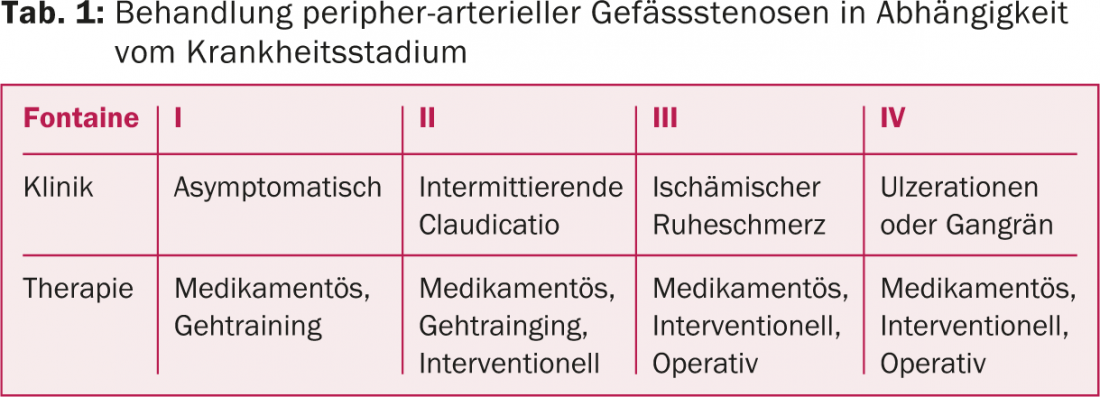

To treat peripheral stenoses, gait training, interventional or surgical therapies are indicated depending on the stage of the disease (Table 1).

Fontaine’s stage I and II pAVD can be treated conservatively in many cases. From stage II, additional interventional procedures are used. From stage III and IV, an interventional or surgical approach is usually the treatment of choice.

In the following, the conservative therapy options for patients with pAVK will be discussed.

Drug therapy

Platelet aggregation inhibition to improve rheology and therapy with statins are standard in patients with pAVK. Statins have pleomorphic properties beyond cholesterol-lowering effects, which have a beneficial effect on the progression of pAVD. Thus, in addition to a significant reduction in strokes, a prolongation of walking distance was recorded with statins compared with placebo [4].

Walk training

The therapeutic possibilities of (walking) training, which can be performed up to stage II, are known to only a few. Several studies have shown that a structured exercise program is equivalent to interventional therapy in terms of increasing pain-free and absolute walking distance in patients with stage I and II PAOD [5]. Furthermore, patients with an exercise-based therapy approach to the treatment of PAOD require fewer invasive procedures overall [5], and it is a cost-effective therapy [6] (Fig. 4).

Exercise causes improvement in endothelial function and capillarization, as well as better O2 depletion in the periphery [7]. An increase in collateralization has not been demonstrated in studies. The improved perfusion further leads to an economization of movement sequences and a remodeling of the musculature, which results in a further improvement in performance. Interestingly, improvement in pain-free walking distance has been shown for different types of exercise [8]. In addition to running training, positive effects have also been demonstrated for ergometer or strength training, and upper arm training was also effective [9]. Patients who can only participate in walking training to a limited extent can thus use alternative forms of training to improve their condition and extend their walking distance. Such alternative training may also be considered in Fontaine’s stage III, but exercise-based training is contraindicated in stage IV. Positive effects of training can be expected especially in patients with proximal lesions in whom good ankle closure pressures are still measurable (optimal >80 mmHg). A long history or a limiting concomitant disease, both of which limit physical training, have an unfavorable effect on training success.

Improvement of the cardiovascular risk profile

Improvement in the prognosis of patients with PAOD is only achieved by improving the cardiovascular risk profile [7]. The most important risk factor, but also the most difficult to control, is cigarette smoking. Cigarette use leads to more rapid progression of pAVD, increased amputations, and significantly increased cardiovascular mortality [10]. Hypertension, hypercholesterolemia, obesity, and diabetes are other risk factors with an impact on prognosis [11]. Optimal adjustment of blood pressure can reduce cardiovascular events. In general, blood pressure values <140/90 mmHg are targeted – the contraindication to beta-blockers that used to exist from stage III onwards has been lifted. In diabetics, an HbA1c below 6.5 should always be achieved and blood pressure values below 130/85 mmHg should be aimed for [12]. Under statin therapy, the target value for LDL cholesterol is <1.8 mmol/l.

Comprehensive therapy through PAVK rehabilitation – Best Medical Treatment?

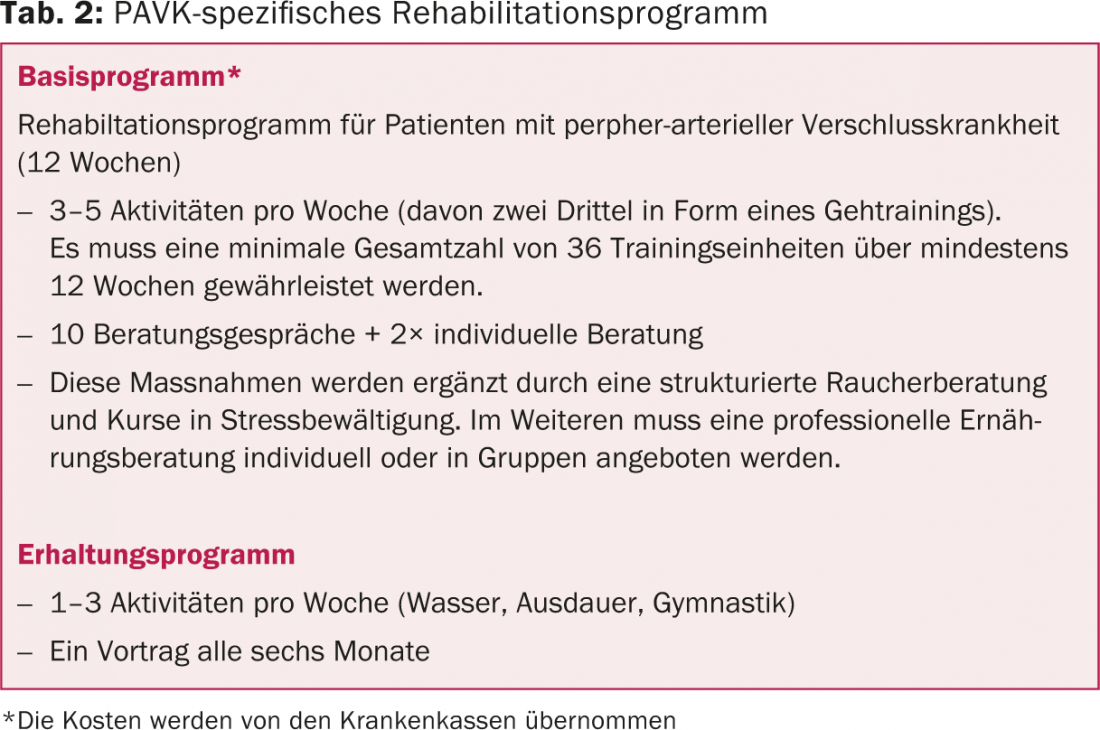

An outpatient rehabilitation program specific to PAOD (Table 2) is currently the only option for comprehensive treatment of patients. The costs of such a twelve-week outpatient rehabilitation program are covered by health insurance. The combination of supervised and professionally guided training in conjunction with modification of risk factors and optimization of drug therapy through close monitoring by physicians and associated services allows improvement of symptoms and prognosis [13]. Continuity of care provides support for patients to make necessary behavioral changes.

Overall, a walking distance increase of 50-200% can be achieved through training. To achieve optimal success (i.e., improvement in walking distance), appropriate training must be performed at least three times per week for 30 minutes over a period of at least three months [14]. Supervised training is superior to independent training [15,16].

As part of a rehabilitation program, patients are motivated to engage in regular physical activity and, in particular, learn adequate and efficient gait training. The training program usually includes various forms of exercise in order to appeal to as many patients as possible and to motivate them to integrate physical activity into their daily lives. Thus, running training is carried out in alternation with other forms of training. Patients are asked to run at a predetermined intensity until pain onset, after which a break is taken until pain recovery has set in. The concept of training into the pain range was abandoned due to reduced patient compliance. Moreover, the additional benefit of such training “in the ischemic area” could not be demonstrated with certainty.

To best address secondary risk factors, smoking history and readiness to quit are evaluated by specialized smoking cessation counseling as standard. If there is a desire to stop smoking, behavioral therapy supported by medication takes place if necessary. The availability of such services in rehabilitation programs allows patients easy access – close supervision during the rehabilitation program increases the chances of success. Accompanying lectures and comprehensive nutritional counseling support self-responsible behavioral change, which in the long term improves the risk profile and prognosis. With the assistance of a psychologist, it is often more feasible to modify psychosocial factors that interfere with compliance and long-term treatment success.

Summary

Structured rehabilitation programs for patients with PAOD implement the multimodal therapy concept recommended in the guidelines. Patients learn structured and efficient exercise and improve their cardiovascular risk profile, which explains the long-term positive outcomes with lower overall intervention rates. Multimodal rehabilitation is the only therapy concept that goes beyond the treatment of local symptoms in the long term and thus also improves the prognosis of patients. The costs of the program are covered by health insurance companies in accordance with the Swiss Health Care Benefits Ordinance.

Literature:

- Selvin E, Erlinger TP: Prevalence of and risk factors for peripheral arterial disease in the United States: results from the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey, 1999-2000. Circulation 2004; 110(6): 738-743. Epub 2004/07/21.

- Spronk S, et al: Impact of claudication and its treatment on quality of life. Seminars in vascular surgery 2007; 20(1): 3-9. Epub 2007/03/28.

- Tendera M, et al: ESC Guidelines on the diagnosis and treatment of peripheral artery diseases: Document covering atherosclerotic disease of extracranial carotid and vertebral, mesenteric, renal, upper and lower extremity arteries: the Task Force on the Diagnosis and Treatment of Peripheral Artery Diseases of the European Society of Cardiology (ESC). European heart journal 2011; 32(22): 2851-2906. epub 2011/08/30.

- Mohler ER, Hiatt WR, Creager MA: Cholesterol reduction with atorvastatin improves walking distance in patients with peripheral arterial disease. Circulation 2003; 108(12): 1481-1486. Epub 2003/09/04.

- Fakhry F, et al: Long-term clinical effectiveness of supervised exercise therapy versus endovascular revascularization for intermittent claudication from a randomized clinical trial. The British journal of surgery 2013; 100(9): 1164-1171. epub 2013/07/12.

- Spronk S, et al: Cost-effectiveness of new cardiac and vascular rehabilitation strategies for patients with coronary artery disease. PloS one 2008; 3(12): e3883. Epub 2008/12/10.

- Hamburg NM, Balady GJ: Exercise rehabilitation in peripheral artery disease: functional impact and mechanisms of benefits. Circulation 2011; 123(1): 87-97. Epub 2011/01/05.

- Lauret GJ, et al: Modes of exercise training for intermittent claudication. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2014; 7: CD009638. Epub 2014/07/06.

- Parmenter BJ, et al: A systematic review of randomized controlled trials: walking versus alternative exercise prescription as treatment for intermittent claudication. Atherosclerosis 2011; 218(1): 1-12. epub 2011/05/24.

- Lu L, Mackay DF, Pell JP: Meta-analysis of the association between cigarette smoking and peripheral arterial disease. Heart 2013. Epub 2013/08/08.

- Kjeldsen SE, Aksnes TA, Ruilope LM: Clinical Implications of the 2013 ESH/ESC Hypertension Guidelines: Targets, Choice of Therapy, and Blood Pressure Monitoring. Drugs in R&D 2014; 14(2): 31-43. Epub 2014/05/21.

- Adam DJ, Bradbury AW: TASC II document on the management of peripheral arterial disease. European journal of vascular and endovascular surgery : the official journal of the European Society for Vascular Surgery 2007; 33(1): 1-2. Epub 2006/12/13.

- Norgren L, et al: Inter-Society Consensus for the Management of Peripheral Arterial Disease (TASC II). European journal of vascular and endovascular surgery: the official journal of the European Society for Vascular Surgery 2007; 33 Suppl 1: S1-75. Epub 2006/12/05.

- Gardner AW, Poehlman ET: Exercise rehabilitation programs for the treatment of claudication pain. A meta-analysis. JAMA : the journal of the American Medical Association 1995; 274(12): 975-980. Epub 1995/09/27.

- Bendermacher BL, et al: Supervised exercise therapy versus non-supervised exercise therapy for intermittent claudication. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2006(2): CD005263. Epub 2006/04/21.

- Fakhry F, et al: Supervised walking therapy in patients with intermittent claudication. Journal of vascular surgery 2012; 56(4): 1132-1142. Epub 2012/10/03.

CARDIOVASC 2014; 13(6): 30-33