Neurorehabilitation after stroke should start as early as possible. Symptom remission is significantly greater under neurologic rehabilitation treatment than under spontaneous recovery. In addition to the interdisciplinary setting, modern therapy methods are to be integrated into the individual treatment. Complication treatment and treatment of secondary consequences should take place permanently, even many years after primary rehabilitation, if necessary also in the context of a renewed inpatient measure. Since the human nervous system is exceedingly complex, differentiated neurological rehabilitation after stroke is still one of the great challenges in contemporary neurology.

Despite modern treatment options, stroke remains the most common cause of long-term disability in adulthood. In Switzerland, 16,000 strokes occur per year [1]. Etiologically, about 15% of strokes are due to cerebral hemorrhage and about 85% are due to reduced perfusion (ischemia, infarction) of the brain. Causes of reduced perfusion include cardiac emboli, occlusion of smaller arteries (subcortical lacunar infarcts), atherosclerosis of large arteries, vasculitis, dissection, coagulopathy, and other causes [2]. As a rule, the localization of the brain damage with the resulting functional impairments is much more relevant for the outcome than the pathophysiology and etiology.

Prognosis and outcome

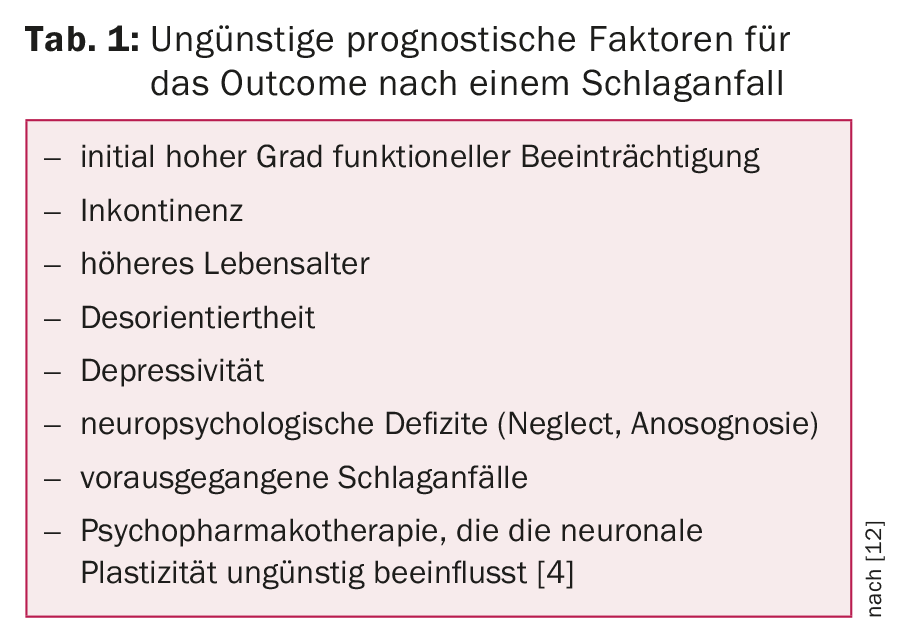

Approximately 10% of affected individuals recover fully and show no residual deficits, minimal deficits persist in approximately 25%, and moderate to severe deficits persist in approximately 40%. About 10% require intensive long-term care due to permanent severe impairments. Approximately 15% of those affected die during the (initial) event. Furthermore, approximately 13-14% suffer a second event within one year [3]. Table 1 provides an overview of unfavorable prognostic factors for outcome after stroke.

Influencing neuroplasticity through neurorehabilitation.

When neuronal tissue is injured, e.g. by a stroke, the so-called neuroplasticity plays an important role – i.e. the property of individual synapses, nerve cells and entire brain areas to change or adapt depending on their use. On the one hand, this occurs as a reaction to injuries of the neuronal tissue. On the other hand, it is also a natural process that allows the organism to respond and adapt to changes in the environment. Neuroplasticity is thus the basis of all learning processes and very important in neurorehabilitation. Different phenomena play a role here:

- Unmasking: recruitment of prelesionally unused neuronal connections in the event of failure of the usual circuitry.

- Vicariation: Functional takeover of a disturbed brain area by other areas.

- Sprouting: Under the influence of neurotropic factors, sprouting of axons occurs with new formation of functional synapses.

- Diaschisis: Lesions of one brain area may initially negatively functionally affect brain areas far from the lesion site.

After acute CNS lesions, a period of increased neuroplasticity lasting at least three to four months may be observed. Even beyond the spontaneous remission phase, which can last more than a year, functionally effective exercise-induced neuroplasticity can be demonstrated with the application of intensive neurorehabilitative therapy measures.

Modern concept of neurorehabilitation

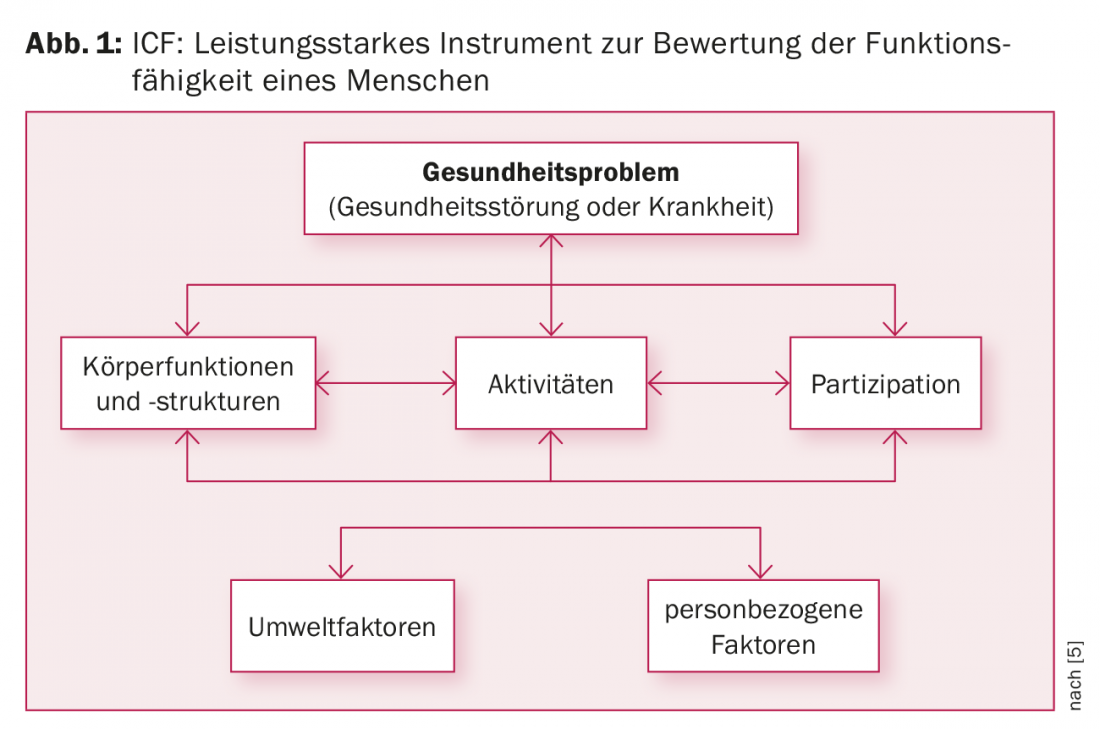

The WHO International Classification of Functioning, Disability and Health (ICF), which was introduced in 2001, is a powerful tool for assessing a person’s functioning. It is also used in modern contemporary neurorehabilitation [5]. This provides a description of functional health status, disability, social impairments, and relevant environmental factors. Here, body functions and structures, activities and social participation as well as environmental and person-related “context factors” are operationalized (Fig. 1). ICF is also the common language of the multiprofessional treatment team in neurorehabilitation, which consists of physicians, physiotherapists, occupational therapists, neuropsychologists, speech therapists, occupational, activation and leisure therapists, and occupational clarifiers, and serves to promote interdisciplinary networking.

Rehabilitation after a stroke usually begins in the stroke units of acute hospitals and is then usually continued in specialized inpatient facilities/specialized clinics.Physicians: They are responsible for the differentiated assessment of specific neurological clinical pictures and the treatment of medical problems and complications/emergencies that arise in the course of the treatment. Medical care is provided after a detailed medical history and internal neurological examination at the beginning of the measure. This applies in particular to the coordination and monitoring of the rehabilitation with optimal individual adaptation of the rehabilitation program to the patient’s deficits and needs. The most important prerequisite for the success of rehabilitation is a stable physical condition. Furthermore, a reduction of (cardiovascular) risk factors especially with regard to a prevention of possible recurrences is also crucial for the treatment.

Rehabilitation care: It supports patients in the implementation of the skills achieved in the therapies and the activities of daily living (ADL): e.g. mobilization from bed, food intake, personal hygiene, taking medication, etc.. Depending on the respective functional level, activities are promoted individually, i.e. guided or taken over vicariously. Nursing tasks are a key component of the multidisciplinary treatment process. As close caregivers, nurses mediate between patients, physicians/specialist therapists and family members.

Physical therapists: they specialize in training the movements of extremities affected by motor and sensory deficits, as well as body stability and balance responses. Mobilization from bed, gait stability and (independent) locomotion are the main focus.

Occupational therapists: They deal with the activities of daily living that serve self-care, such as personal hygiene, food intake and the targeted functional use of the extremities. In our clinic, they work closely with the physiotherapists in the sensorimotor team and interact with them, e.g. in initiating movement by reducing spasticity or promoting movement through targeted body awareness training. Modern machine-assisted therapies (robotics) are playing an increasingly important role in this field [6,7].

Multiple impairments

Strokes often also result in speech impairments, some of which are temporary, but some are long-term or even permanent. These include articulation disorders (dysarthrias or dysarthrophonias), apraxic speech disorders (buccofacial apraxia), and voice disorders (dysphonia), as well as receptive, expressive, or global speech disorders (aphasias) with sometimes accompanying impairments in reading and writing (dys-/alexia or dys-/agraphia). In addition, for various reasons, acute dysphagia occurs in 50% of all stroke patients and chronic dysphagia in 25% [8].

Speech therapy: The disorders are diagnosed and evaluated with the help of appropriate examination procedures. Therapeutically, in addition to specific exercise programs for voice/syllable/word and sentence formation, teaching of compensation strategies, facio-oral forms of therapy (e.g. F.O.T.T. according to Kay-Coombes) and targeted swallowing training play an important role. In cases of severe dysphagia where patients are fitted with a tracheostomy tube, a supplementary radiological or endoscopic examination of the swallowing process may be required prior to decannulation.

Neuropsychology: In most cases, strokes also cause temporary or permanent cognitive impairments and mental abnormalities, which include attention (e.g., neglect often in right hemisphere lesions), memory and concentration disorders, visual-spatial perception disorders (e.g. hemi-/quadrant anopsia in infarcts in the supply area of the anterior choroid and posterior cerebral arteries) as well as reading and arithmetic disorders (often in cases of damage to the language-dominant hemisphere) and disorders of executive functions (e.g., self-motivation, volition, impulse control, goal setting, action planning, etc.).

The disorders are first precisely evaluated with appropriate (also computer-assisted) test procedures and targeted explorations and then specifically addressed. Disorders of behavior and affect in the context of concomitant organic psychosyndrome (OPS) are also treated by neuropsychologists. In addition to psychopharmacological treatment, the “post-stroke depression” [9] observed in about 20-25% of stroke patients sometimes requires (supportive) psychotherapeutic intervention. This is also required for more severe (usually anxious-depressive) adjustment disorders as part of illness management. Many of the dysfunctions described above have a negative impact on occupational performance and fitness to drive. The latter is often at least temporarily impaired after a stroke. The duration of the incapacity to drive depends on the type and severity of the motor and cognitive impairments and is determined by the treating physicians.

Occupational, activation and recreational therapy: This rounds off the therapeutic offering. The skills regained and compensatory strategies learned in sensorimotor and neuropsychology are implemented and trained there (relevant to everyday life). In the case of occupationally active patients, an occupational clarifier is called in during the course after the start of occupational therapy, who initiates an occupation- or activity-specific evaluation and, if necessary, contacts the employer and/or the disability insurance.

Social service: It continuously accompanies the entire rehabilitation process in order to set the course for the smoothest possible transition to the post-inpatient phase at an early stage. Important questions need to be clarified: Further care in the home environment with the organization of appropriate assistance/support measures (e.g. Spitex, home help, meal service) or, in the case of a continuing or permanent need for assistance/care, accommodation in a suitable transitional or residential/nursing facility. In the case of employed persons, it must also be clarified whether and to what extent they can continue their professional activities after the illness. In addition to a preliminary occupational assessment, which can be carried out at least in part during occupational therapy, the following measures play a major role: pre-planning and accompanying discussions with the employer and/or contacting the disability insurance (IV) in order to initiate targeted support measures (e.g. job coaching, adaptation of the workplace, etc.) or a pension procedure. Social services also play an important role in counseling patients and their relatives during the rehabilitation process. He is also an important link in the therapeutic team: He is responsible for organizing and structuring information and exit interviews with the patient, his relatives and the attending physicians, therapists and nurses.

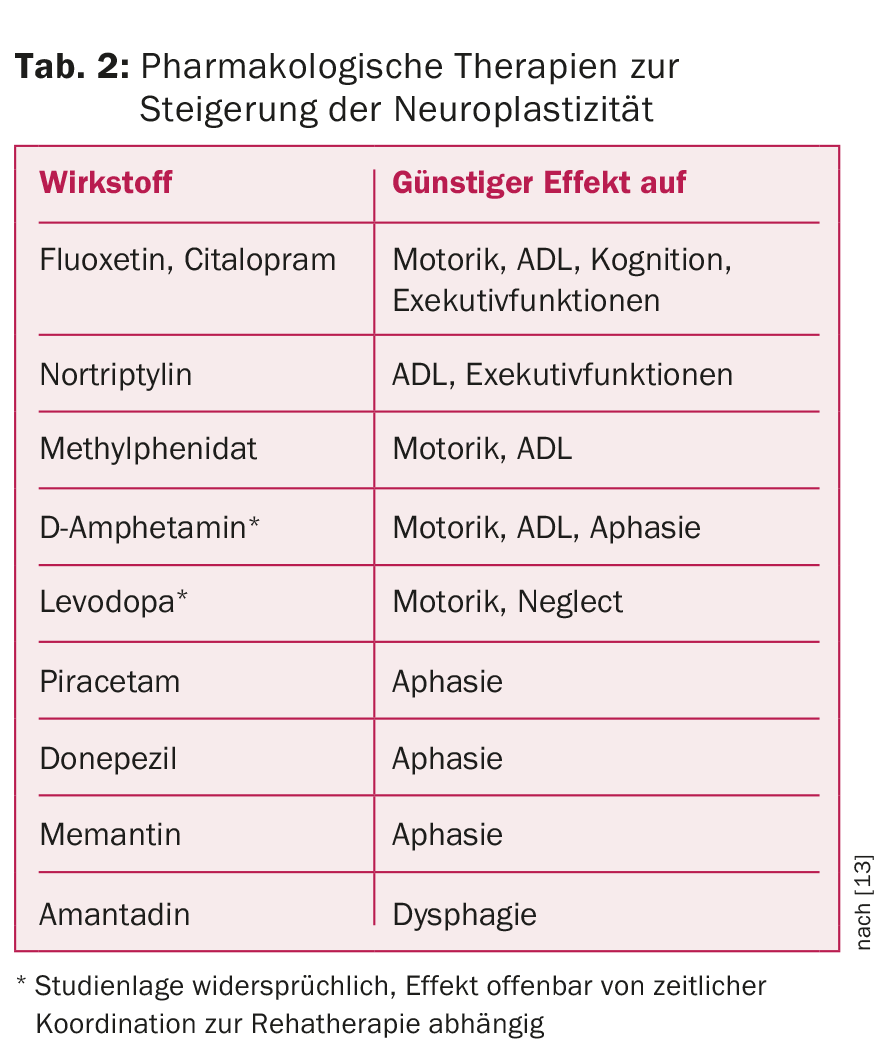

Experimental procedures such as pharmacological therapies to increase neuroplasticity (Table 2), repetitive transcranial magnetic stimulation (rTMS) [10] and transcranial direct current stimulation (tDCS) [11] are used to improve outcomes in neurorehabilitation. For spasticity treatment, in addition to topical botulinum toxin injections, drug pumps for continuous intrathecal baclofen administration are already established.

Primary rehabilitation occurs in the first three to six months after the cerebrovascular event. The duration of (inpatient) rehabilitation depends on the type and severity of the deficits and is usually around four to twelve weeks.

In the post-inpatient phase, the rehabilitation process is continued on an outpatient basis at the patient’s old/new place of residence, provided that impairments relevant to everyday life still exist. Rehabilitation after a stroke often lasts a lifetime. For treatment of secondary sequelae or complications or persistent severe impairment, inpatient interval therapy may be helpful.

Literature:

- Meyer K, et al: Stroke events and case fatalities in Switzerland based on hospital statistics and cause of death statistics. Swiss Med Wkly 2009; 139(5-6): 65-69.

- Adams HP, et al: Classification of subtype of acute ischemic stroke. Definitions for use in a multicenter clinical trial. TOAST. Trial of Org 10172 in Acute Stroke Treatment. Stroke 1993; 24(1): 35-41.

- Hankey GJ: Long-term outcome after ischaemic stroke/transient ischaemic attack. Cerebrovasc Dis 2003; 16 Suppl 1: 14-19.

- Kwakkel G, et al: Predicting disability in stroke – a critical review of the literature. Ageing 1996 Nov; 25(6): 479-489.

- German Institute of Medical Documentation and Information (DIMDI) (ed.): International Classification of Functioning, Disability and Health (ICF). WHO, Geneva 2005.

- Pignolo L: Robotics in neuro-rehabilitation. J Rehabil Med 2009 Nov; 41(12): 955-960.

- Mehrholz J, Pohl M: Electromechanical-assisted gait training after stroke: a systematic review comparing end-effector and exoskeleton devices. J Rehabil Med 2012 Mar; 44(3): 193-199.

- Broadley S, et al: Predictors of prolonged dysphagia following acute stroke. J Clin Neurosci 2003 May; 10(3): 300-305.

- Huff W, Steckel R, Sitzer M: “Poststroke depression.” Neurologist 2003; 74(2): 104-114.

- Sook-Lei L, et al: Non-invasive brain stimulation in neurorehabilitation: local and distant effects for motor recovery. Front Hum Neurosci 2014; 8: 378.

- Rosset-Llobet J, et al: Effect of Transcranial Direct Current Stimulation on Neurorehabilitation of Task-Specific Dystonia: A Double-Blind, Randomized Clinical Trial. Med Probl Perform Art 2015 Sep; 30(3): 178-184.

- Müller F, Walther E, Herzog J (eds.): Practical neurorehabilitation. Treatment concept after damage to the nervous system. 1st edition 2014: Verlag W. Kohlhammer.

- Hacke W (ed.): Neurology. 14th edition 2016: Springer-Verlag Berlin Heidelberg.

CARDIOVASC 2016; 15(4): 8-12