Patients with pulmonary embolism require anticoagulation for a period of at least three months. Before starting therapy, several considerations must be addressed: Which anticoagulant is the most appropriate for this patient, what should be the duration of anticoagulation? And what is the risk-benefit ratio?

Acute pulmonary embolism is considered the most serious manifestation of venous thromboembolism (VTE). For the acute and maintenance phases, the goal of antithrombotic therapy is to prevent progression of thrombosis and dissolve thrombotic material. In the initial phase, routine clinical practice is usually performed parenterally using unfractionated heparin (UFH), low-molecular-weight heparins (NMH), and fondaparinux.

Initial phase

Low-molecular-weight heparins and fondaparinux are therapy of choice for initial parenteral anticoagulation in patients who are not considered high-risk classified. Compared with UFH, NMH and fondaparinux offer advantages in terms of efficacy, safety, and practicality, for example, a more stable drug level and thus anticoagulation effect, higher efficacy, lower risk of major bleeding or heparin-induced thrombocytopenia (HIT), and an easier route of administration by subcutaneous injection 1-2 times daily. These advantages outweigh the disadvantage of the slightly slower onset of action. As an alternative to parenteral anticoagulation, therapy with the oral factor Xa inhibitors apixaban and rivaroxaban may be considered in non-high-risk patients.

In contrast, the situation is different in patients who are hemodynamically unstable and at very high risk of embolism. In them, therapeutic anticoagulation with UFH should be initiated immediately, i.e., as soon as the suspected diagnosis is made, write Dr. Matthias Ebner and Dr. Mareike Lankeit of Charité – Universitätsmedizin Berlin (D) [1]. According to the study, hemodynamically unstable pulmonary embolism patients are at risk for a high lethality rate, especially in the first few hours. Intravenous bolus administration of UFH (usually 5000 IU) was superior to the subcutaneously administered alternatives NMH and fondaparinux, the researchers said. Especially if there is centralization with decreased tissue perfusion in obstructive shock. As a subsequent continuous infusion, they initially recommend 1000 IU per hour with the goal 1.5-2.5-fold prolongation of the partial thromboplastin time (aPTT).

Acute and maintenance phase

Vitamin K antagonists (VKA) have long been the most commonly used preparations for therapeutic anticoagulation. However, they are limited by factors such as their narrow therapeutic window, drug and food interactions, and the need for dose adjustment including monitoring (INR measurement). An alternative to VKAs are non-vitamin K-dependent oral anticoagulants (NOAKs), which include dabigatran, apixaban, edoxaban, and rivaroxaban. In 2019, the European Society of Cardiology (ESC), in collaboration with the European Respiratory Society (ERS), published its new guideline that NOAKs should be preferred over VKAs for oral anticoagulation of patients with pulmonary embolism (in the absence of contraindications). Contraindications to NOAKs include severe renal insufficiency, impaired liver function, pregnancy or lactation, and antiphospholipid syndrome.

Currently, different strategies are available for the therapy of oral anticoagulation in patients with pulmonary embolism, Dr. Ebner and Dr. Lankeit write: the “traditional” regimen consists of overlapping dual anticoagulation with NMH and overlapping switch to a VKA (target INR 2.0-3.0). In addition, there is a sequential dual therapy with initial NMH for at least 5 days and subsequent switch to therapy with dabigatran or edoxaban (in maintenance dose) as well as monotherapy with rivaroxaban or apixaban (in each case in initial higher dosage). According to the experts, a dose reduction of NOAK should only be carried out after critical review and restrictively in the first 6 months after a pulmonary embolism. In pulmonary embolism patients who also have cancer, anticoagulation should be continued until the cancer is considered cured.

Secondary prophylaxis

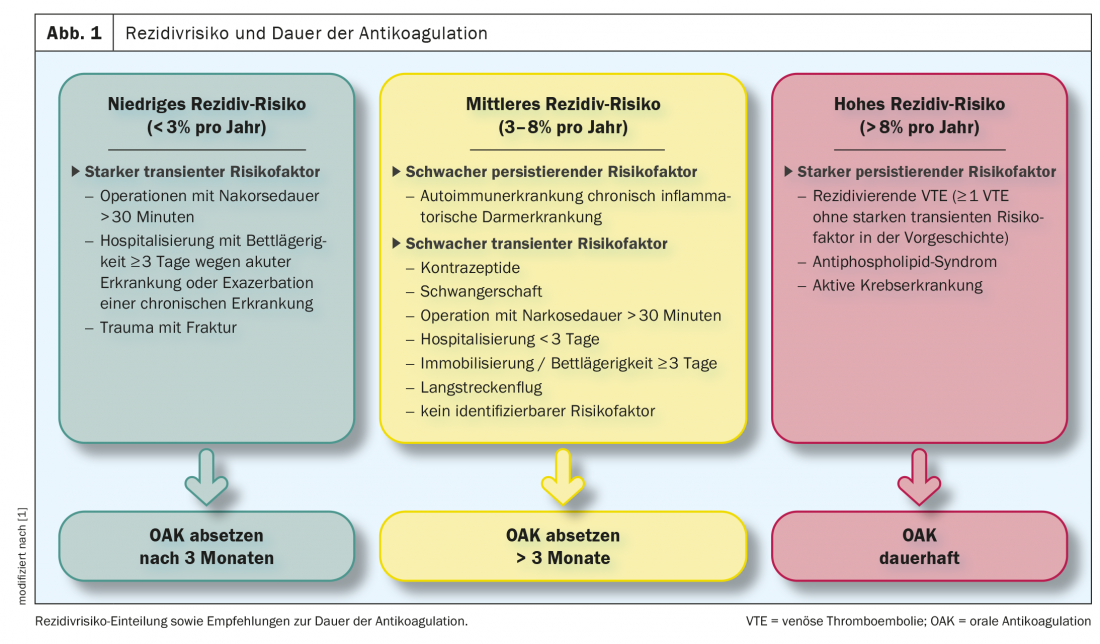

Secondary prophylaxis is used to prevent recurrence of thromboembolism. In the 2019 ESC guideline [2], patients with pulmonary embolism are divided into 3 groups with regard to the risk of recurrence. Groups divided (Fig.1). Consequently, in patients in whom a strong transient/reversible risk factor was present at the onset of PE (e.g., hip or knee replacement surgery or trauma with fracture), the risk of recurrence may be considered low and anticoagulation may be discontinued after 3 months. An intermediate risk of recurrence with consideration for continuation of anticoagulation indefinitely (with regular risk-benefit assessment) is associated with patients who have either a weak transient/reversible risk factor (e.g., minor surgical procedures, long-distance air travel), a weak persistent risk factor (e.g., active autoimmune disease, inflammatory bowel disease), or no identifiable triggering factor. Patients at high risk of recurrence and recommended for permanent anticoagulation have a strong persistent risk factor (eg, active cancer, antiphospholipid syndrome, or recurrent episodes of VTE not explained by strong transient risk factors).

Literature:

- Ebner M, Lankeit M: Antithrombotic therapy in pulmonary embolism. DMW – Deutsche Medizinische Wochenschrift 2020; 145(14): 970-977; doi: 10.1055/a-0955-3379.

- Konstantinides SV, Meyer G, Becattini C, et al: 2019 ESC Guidelines for the diagnosis and management of acute pulmonary embolism developed in collaboration with the European Respiratory Society (ERS). Eur Heart J 2019; doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehz405.

InFo PNEUMOLOGY & ALLERGOLOGY 2021; 3(1): 39-40.