Pressure ulcers, diabetic foot syndrome and venous leg ulcers are the most common causes of chronic wounds and are becoming an increasingly important topic in dermatology. W.A.R and PEDIS scores are used to assess infection status. In wound care, among other things, careful selection and proper application of the appropriate dressing is critical.

Whereas in the case of small, uncomplicated wounds the body is able to close the body tissue again after a short time through its own biological processes, chronic wounds are by definition characterized by the fact that after a period of 8 to 12 weeks there is no sign of a healing process that corresponds to the treatment. In the lower extremities, approximately 70% of ulcerations are due to venous disease, and 20% are due to peripheral arterial occlusive disease or mixed arteriovenous disease [6]. Peripheral polyneuropathy underlies approximately 85% of foot ulcerations, sometimes in combination with peripheral arterial occlusive disease [6]. Despite optimal therapy, 25-50% of leg ulcers and more than 30% of foot ulcerations do not heal completely within 6 months.

Determine localization and wound environment

Careful vascular diagnosis of chronic wounds with regard to peripheral arterial occlusive disease (PAVD) and venous disease or, in the foot area, peripheral polyneuropathy is part of the diagnostic expertise [1–3]. Local therapy as suggested in the corresponding S3 guideline for chronic wounds with the risk of peripheral arterial occlusive disease, diabetes mellitus, and chronic venous insufficiency is only useful after diagnosis and initiation of causal therapy of the underlying disease [4]. The selection of local therapy is based on the following guiding questions:

- Is there a clean wound bed or is debridement appropriate?

- Are there signs of critical colonization and should antiseptic or antibacterial measures be initiated (e.g., using polyhexanide, octenidine, or silver-containing dressings)?

- Does the wound dressing ensure a physiological moist environment? Should the dressing be modified to absorb more exudate, if necessary, or to add moisture to the wound, if necessary?

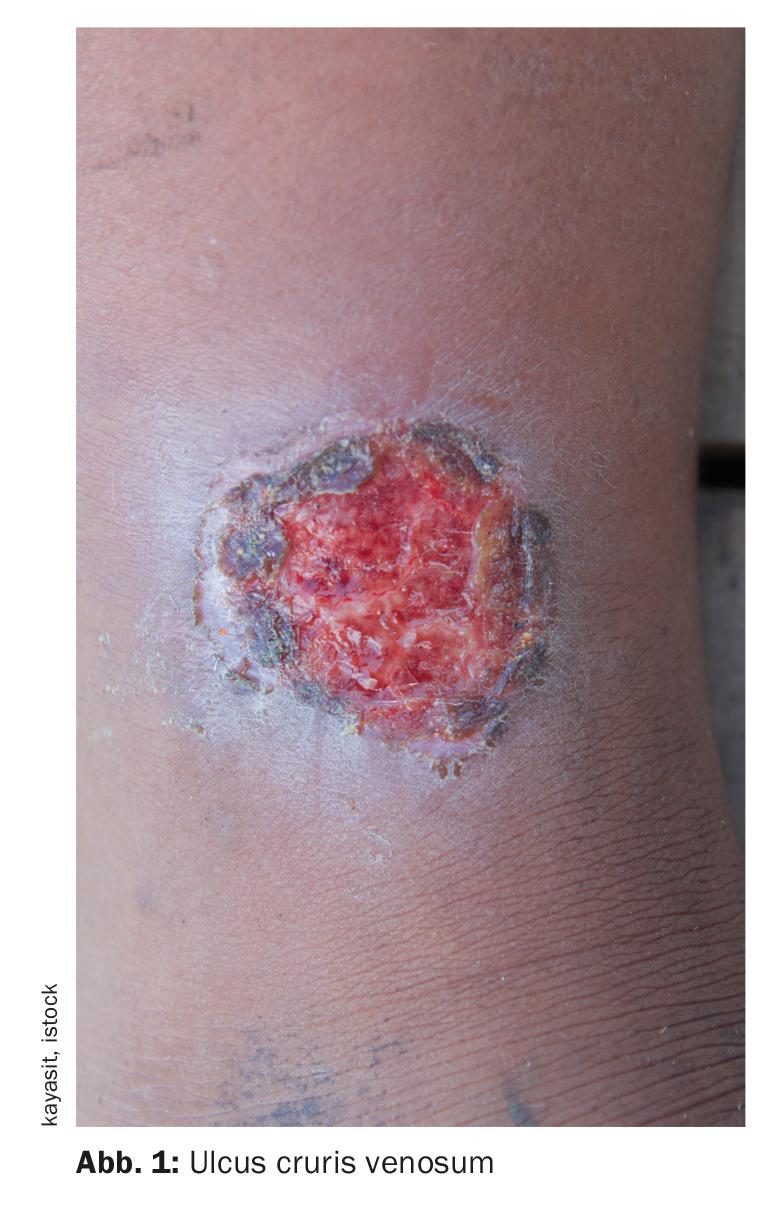

In order to be able to assess the pathogenesis of chronic wounds already on the basis of the clinical picture, the precise localization of the ulceration is helpful [6]. If this is located between the inferior calf and the medial malleolus, a venous genesis may be considered. In contrast, if localization is in the toe, lateral malleolus, and tibial edge, arterial occlusive disease is usually the cause. Polyneuropathy is indicated by the location of the wound at pressure points, particularly on the plantar aspect of the foot, the tip of the toe, and the lateral aspect of the 5th metatarsal. Ulceration of the heel and bony prominences may be due to a decubital mechanism. In addition to location, the wound environment is also informative in determining the genesis of ulceration [6]. While venous ulcers are embedded in eczematous and itchy skin – possibly with hemosiderin deposits, thickening, fibrosis, and edema – arterial ulcers are present in thinner areas of skin with decreased hair growth, temperature, and pallor. In polyneuropathic ulcerations, the surrounding skin is desiccated and hyperkeratotic. It is also important to distinguish between venous leg ulcers and mixed leg ulcers.

Assess infection risk using W.A.R. and PEDIS scores.

Many chronic wounds in clinical practice are associated with a risk of infection. Therefore, topical antimicrobial agents are often used. To facilitate decision making regarding antisepsis of wounds and as a basis for an appropriate treatment regimen to prevent wound infections, the “Wounds-at-risk(W.A.R.) score” was developed [8,9]. It is a clinical assessment tool based on expert consensus that facilitates clinically focused risk assessment based on the specific circumstances of each patient. The indication for the use of antiseptics is derived from the sum of the differently weighted risk causes, for each of which points are awarded. Antimicrobial treatment is warranted for scores of 3 and above.

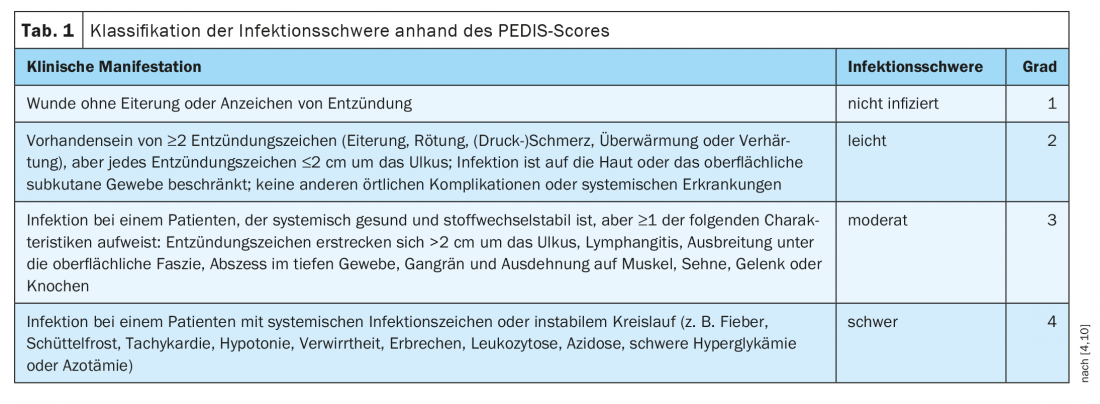

Another classification system for graduating inflammation and infection is the PEDIS score. This classification was originally developed for diabetic foot syndrome, but according to the guideline, it is also suitable for infected wounds caused by pAVK or venous outflow obstruction [4]. The scheme of PEDIS classification is shown in Table 1 .

What should be considered when treating infected wounds?

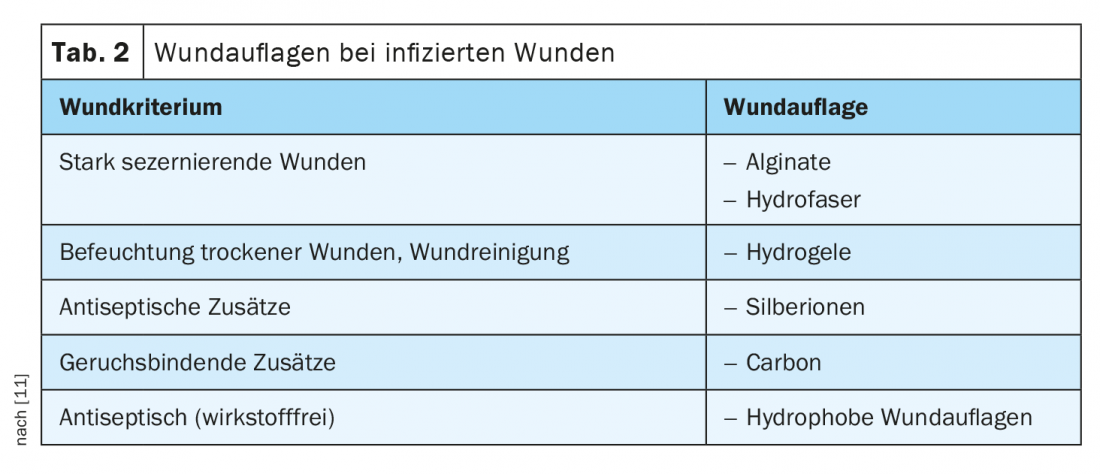

An expert suggestion for criteria to select dressings for infected wounds is shown in Table 2 [11]. In critically colonized and locally infected wounds, antiseptic wound treatment in combination with mechanical wound cleansing is recommended for the elimination of local inflammation caused by human pathogenic microorganisms and as prevention of systemic infectious disease [4]. Antiseptics with octenidine or polihexanide in liquid or gel form can be used, which should not be covered with film-covered wound dressings, as this would create a moist, warm wound environment and further promote infection [13]. Decontamination may be considered if pathogen-induced inflammation is suspected. It is common for chronic wounds to be colonized by microorganisms; according to the guideline, routine determination of pathogens is not necessary with regard to the use of the local antiseptic agents PVPIod, polihexanide or octenidine [4]. Pathogen testing is only indicated when antibiotic therapy is being considered due to evidence of pathogen-related infectious disease. Surgical debridement should be considered in cases of local signs of inflammation, systemic infectious disease originating from the wound area, extensive necrosis [4].

Since infected wounds usually exude heavily and viscously, it makes sense to use products adapted to the wound. These include superabsorbents, alginates and hydrofiber [13]. Alginates are strong gelling agents, which is why they are used for heavily weeping wounds with or without infection [12]. Characteristically, a viscous gel is formed and an enormous swelling and binding capacity. This automatically supports natural wound cleansing. These compresses are available in different versions, for example also with silver ions. Products containing silver have an antibacterial effect by killing germs. Alginates should not be used in very dry and necrotic wounds. Hydrogels have a high water content of 60-95% and are suitable for the treatment of dry wounds [12]. Various dosage forms are available, for example as a transparent compress with or without a fixation edge or as a gel that can be introduced into deeper wounds, where it causes dead tissue to soften (autolytic debridement). Wound gauzes or absorbent compresses can be used above the gel as a secondary covering. Hydrogel dress ings are composed of synthetic, hydrophilic polymers. Hydrogels are not suitable for the care of heavily weeping or bleeding wounds and in cases of a high degree of infection. Hydrophobic dressings bind germs, but should not be combined with fatty gauzes or skin care products, as direct wound contact is required for germ binding and adhesion of the pores should be prevented so that their binding function is maintained. With consistent antiseptic treatment, an infection should have cleared up after two weeks.

Literature:

- Arbeitsgemeinschaft der Wissenschaftlichen Medizinischen Fachgesellschaften: S3-Leitlinie “Peripheral arterial occlusive disease (PAVK), diagnostics, therapy and follow-up”. Registration number 065-003; as at: 30.11.2015.

- Arbeitsgemeinschaft der Wissenschaftlichen Medizinischen Fachgesellschaften: S3-Leitlinie “NVL Typ-2-Diabetes. Prevention and treatment strategies for foot complications”. Registration number nvl-001c; as of Nov. 30, 2006 (under revision).

- Arbeitsgemeinschaft der Wissenschaftlichen Medizinischen Fachgesellschaften: S3-Leitlinie “Diagnostik und Therapie des Ulcus cruris venosum”. Registration number 037-009, as of 01.08.2008 (under revision).

- Arbeitsgemeinschaft der Wissenschaftlichen Medizinischen Fachgesellschaften: S3-Leitlinie “Lokaltherapie chronischer Wunden bei Patienten mit den Risiken periphere arterielle Verschlusskrankheit, Diabetes mellitus, chronisch venöse Insuffizienz”. Registration number 091-001; as of 12.06.2012 (under revision).

- University Hospital Basel: Guideline Wound Management. Status: November 2011.

- Stücker M: Wounds – a significant topic in dermatological practice. Karger Compass Dermatol 2018; 6: 6-7.

- Foss P: Seven questions for Dr. Pierre Foss Winner of the Dermatology Innovation Award 2017. Karger Compass Dermatol 2018; 6: 41-42.

- Stücker M: Classification of high-risk wounds and their antimicrobial treatment with polyhexanide: a practice-oriented expert recommendation. Karger Compass Dermatol 2014; 2: 38-39.

- Dissemond J, et al: Classification of wounds at risk and their antimicrobial treatment with polihexanide: a practice-oriented expert recommendation. Skin Pharmacol Physiol 2011; 24(5): 245-255.

- Morbach S, et al: DDG practice recommendations. The Diabetologist 2020; 16: 54-64.

- Wagner H-O, Diener H: Chronic wounds – the secrets of the wound manager. Family Medicine Continuing Education Hamburg, HFH, 8/13/2019.

- Pharmaceutical Newspaper: Wound Dressings: Aids in Wound Healing, 16.08.2017, www.pharmazeutische-zeitung.de/ausgabe-332017/hilfen-bei-der-wundheilung/

- Protz K, Sellmer W: Correct application of wound dressings. The nurse The nurse 57th year. 6/18, www.werner-sellmer.de

Further reading:

- Stücker M: Wounds – treatment, healing and complications. Karger Compass Dermatol 2018; 6: 8.

DERMATOLOGIE PRAXIS 2021; 31(1): 18-20