Death is increasingly on our minds, especially in the current times, and among other things it makes us think about ethical, moral and legal issues regarding dying. Is it still “allowed” to die just like that today? Who “may” die and who may not? And does every death need to be investigated further in the aftermath? For many general practitioners, certifying death outside the hospital is part of basic care, and knowledge of the obligation to report so-called extraordinary deaths (agTs) and of how to conduct a careful medical postmortem is essential in this regard.

Death is increasingly on our minds, especially in the current times, and among other things it makes us think about ethical, moral and legal issues regarding dying. Is it still “allowed” to die just like that today? Who “may” die and who may not? And does every death need to be investigated further in the aftermath? For many general practitioners, certifying out-of-hospital deaths is part of basic care, and knowledge of the obligation to report so-called extraordinary deaths (agTs) and of how to conduct a careful medical necropsy is essential in this regard.

The extraordinary death

The term extraordinary death (agT) was introduced in the 1960s by the then Zurich medical examiner Fritz Schwarz. It is only used in the German-speaking part of Switzerland, in the French-speaking parts of Switzerland one speaks of the so-called “mort suspect”.

The extraordinary death can be defined as follows:

a) Non-natural death: violent death or death suspected of violence (e.g. accident, suicide, tort, but also: death after/in medical treatment error). The term “violent” is not synonymous with violence by third parties. For example, fatal suicidal poisoning is also referred to as a violent death.

b) Unclear death: A non-natural death is possible. These are sudden and unexpected deaths in which nothing externally indicates violence, but such violence cannot be ruled out. Often, unexplained deaths turn out to be natural deaths after the completed investigations (legal inspection, autopsy, etc.).

In all cantons, there is a corresponding obligation to report extraordinary deaths. It is mostly specified in the cantonal health law. Art. 28 of the Bernese Health Act states, for example: “The professional shall immediately report extraordinary deaths to the competent law enforcement authorities in the course of his or her professional practice.”

With regard to the recognition of an unusual death, the first examining physician thus plays a central role. The belief that only deaths suspected of being felonies need to be reported is as widespread as it is wrong. Every agT is subject to reporting! The obligation to report late deaths in hospital is particularly frequently neglected (e.g. death three weeks after a traffic accident or a fall down stairs). However, it is precisely here that clarification of the causality between event and death would be necessary.

Important: if the first examining physician declares and reports a death as agT (i.e., as a non-natural or unclear death) after any resuscitation measures and certain determination of death, he/she should avoid any further manipulations and examinations of the corpse (incl. the medical post-mortem examination) and at the place where the corpse was found in terms of the protection of traces, since this is then the task of the alarmed police and the forensic medical examiner/medical examiner. Is a medical officer, district or county physician. Death marks are already often clearly visible on exposed parts of the body, and rigor mortis can be palpated even without undressing the corpse.

The natural death

Only natural death is not reportable. A natural death occurs when death is the expected consequence of a known underlying disease at the time of its occurrence and death has occurred without external influence. Furthermore, there must be no evidence of any possible external influence; this applies both to the surroundings and to the corpse itself. The attestation of a natural death necessarily requires a thorough medical postmortem examination of the completely undressed corpse. If a physician certifies a natural death, no downstream investigations by expert personnel take place. With his signature, the physician thus assumes sole responsibility for this death. Therefore, natural death should only be certified if the evidence for it has been comprehensibly consolidated. The requirement for certification of a natural death is significantly higher for the coroner than for the other types of death.

Especially the uninjured corpse without known previous diseases poses a great challenge to the coroner, since here basically everything is possible as a mode of death, including homicide (e.g. suffocation by soft covering, poisoning, etc.). In addition, it must be ruled out that the death could not be the result of an event that occurred longer ago (e.g., traffic accident, suicide attempt, etc.). The death does not necessarily have to be the direct result of injuries sustained. Pneumonia or pulmonary embolism following an accident and hospitalization, for example, are also ultimately a consequence of the initial event. One must therefore ask: would the person at this point in time have very probably also died without the initial event (accident/suicide attempt/body injury) or would he/she probably still be alive without this event? Correctly declaring a death as agT – i.e., non-natural or unexplained death – may result in not only criminal, but also civil and insurance consequences. For example, declaring an accidental death as natural may deny the dependents insurance money to which they are entitled.

However, a natural death must also be reported in the following case, for example: The symptoms and the course of the disease presumably indicate death from a heart attack. During the clarification, it turns out that the patient had been to a doctor shortly before his death and that the doctor may not have recognized an ECG or laboratory finding indicating an infarction or that the patient had not been seen by a doctor. has not carried out the necessary investigations and has not taken the necessary measures. In this case, there may be legally significant external factors, namely evidence of a medical error of treatment by omission.

In the following circumstances, reporting of the death is indicated even if there are no specific findings against natural death after the death has been determined:

- Limited assessability of the corpse (rotting corpses etc.)

- Identity not secured

- Striking circumstances

- Disputes, threats in advance

- Non-intact locking conditions (e.g. open apartment door)

- Acute disorder in the apartment

- Deaths in the milieu (prostitution, drugs, etc.)

- Medical treatment or consultation shortly before death (prevention of accusations or rumors).

- Death in custody or police custody

- Death related to possible diagnostic or treatment error (could be a tort, but should be reported as an unclear death in the spirit of not prejudging)

- Evidence of a change in the position of the corpse (e.g., death marks that are not in the correct position).

- Persons who are in the public interest (prevention of rumors).

Note: The mere absence of injuries is not an indication of natural death, and natural death is not a catch-all for deaths with no clues as to the manner of death!

The medical postmortem

If, after a death has been determined with certainty, the first examining physician concludes that a death can in all probability be classified as natural after examining the circumstances, he or she must conduct a thorough medical postmortem. The coroner must personally perform the examination of the deceased, which he confirms with his signature on the death certificate (Fig. 1) . A prerequisite for the careful performance of a medical postmortem is the complete undressing of the corpse. In the case of a corpse with, for example, complete rigor mortis, undressing the upper body may be more difficult. In any case, all skin regions must be inspected. The aim is to collect possible indications of self-inflicted or external influence (injuries, foreign bodies, suspicious traces, etc.).

The entire surface of the body must be inspected. Bandages, plasters or other structures covering the surface of the body should be removed or the skin underneath should also be examined. All body orifices (nasal, oral, auditory, genital, anal) must be inspected and assessed for abnormal contents.

As soon as during the medical post-mortem examination injuries or other findings (e.g. the post-mortem findings do not match the assumed time of death), or circumstances are found that raise doubts about a natural death, resp. the overall situation changes in such a way that a report must be made, the postmortem must be stopped, the site secured and the police notified immediately.

The following list gives some examples of findings (in addition to findings conspicuous for e.g. gunshot, cut or stab wounds) that should be examined in any case in addition to rigor mortis and death marks.

Head:

- Palpation of the scalp for swelling or blood adhesions

- Bleeding from auditory canal (skull fracture)

- Knocking on the skull – skull rattling (skull fracture)

- Monocle or spectacle hematomas

- Stasis bleeding in the eyelids and/or conjunctiva, oral mucosa, facial skin and skin behind the ears (strangulation)

- Coatings inside the nose, defects of the nasal septum (cocaine abuse).

- Abutment injuries in the vestibule of the mouth (blunt force trauma to the face)

- Contents of the oral cavity and pharynx (bolus death, aspirations)

- Tongue bite (epilepsy)

- Foam fungus (drowning, intoxications)

Neck:

- Thorough inspection of the neck skin for possible desiccation, strand or choke marks or strangulation marks (these may be very subtle to not visible at all).

- Checking the stability of the head and neck joints (cervical spine fracture)

- Neck vein congestion

Hull:

- Skin emphysema

- Injuries of the skin mantle

- Percussion over thorax (pneumothorax)

- Stability of the thorax (rib fractures)

- Fluctuation in the abdomen (ascites, free blood)

- Stability of the shoulder girdle, spine and pelvic ring

Genitals/Anus:

- Injuries

- any adhesions (sperm)

- Foreign content (body packing, conspicuous objects)

Extremities:

- Stability

- Leg circumference differences (thrombosis)

- Edema

- puncture sites (fresh, if blood can be squeezed off)

Hands:

- conspicuous applications (blood, powder, drugs, soot, etc.)

- Defensive Injuries

- Current brands

- fresh imposing fingernail clippings

Signs of death and time of death estimation

Definite signs of death are death stains, rigor mortis, decay, and injuries incompatible with life. They are used to establish death with certainty, to estimate the time of death, occasionally to diagnose the cause of death (e.g., bright red death stains in CO poisoning, sparse or absent death stains in exsanguination, etc.), and to detect postmortem positional changes (e.g., death stains not consistent with position or rigor mortis) forensically. For example, decapitation or dehibernation are considered injuries incompatible with life. A fall from a height or a severing of limbs does not necessarily lead directly to death. Unpalpable pulse, undetectable breathing, low body temperature, etc. are not sure signs of death. Particular danger exists in the case of hypothermia, which is also possible at lower room temperatures. Attention: so-called apparent deaths (i.e. persons who are falsely declared dead due to an inadequate determination of death) also occur in our country time and again.

Estimating time of death remains one of the most difficult tasks in forensic medicine because numerous factors influence postmortem findings. Estimation also means that it is virtually impossible to give an exact time for deaths that occurred unobserved. Therefore, possible time periods are always mentioned within which death is likely to have occurred with a probability, but not with certainty. A realistic estimate always includes a time window of at least 3 hours. As a general rule, the fresher a corpse, the more accurate an estimate can be made.

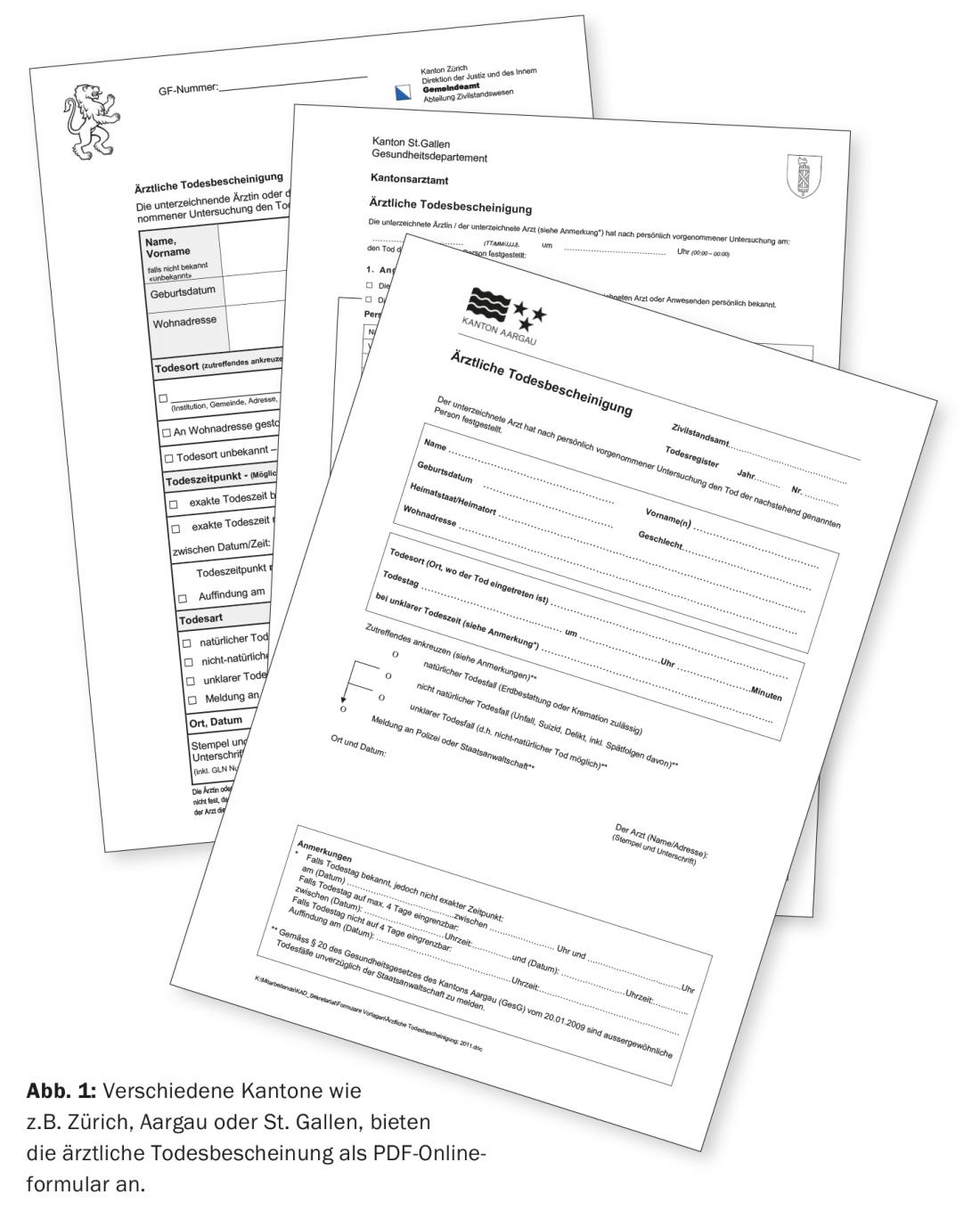

Death marks (also: livor mortis or livores): Death stains are the earliest certain sign of death. They appear already approx. 20-30 minutes after the onset of death (fig. 2 and 3) and are livid (bluish-violet), initially patchy, later extensive discolorations of the skin on the dependent (facing the earth) parts of the body with recesses on the support surfaces, clothing folds or the like. Death spots are caused by blood filling the blood vessels as a result of sinking of the no longer circulating blood according to the force of gravity. In the course of time, the blood gradually thickens, which is why the death spots can initially be wiped away, then only pressed away, and finally, after about 20-30 hours, they can no longer be pressed away. In the first 6 hours after death, they are still completely rearrangeable, and about 6-12 hours after death, they are still partially rearrangeable.

Sparse or absent deathmarks may indicate anemia or relevant blood loss externally or internally, or may occur, for example, in bodies recovered from bodies of water (water pressure compresses blood vessels in the skin externally). Bright red death spots occur in carbon monoxide poisoning and in cold weather. “Vibices” are postmortem, small, punctate, usually dark purple or blackish blood leaks into the skin within the mortal remains.

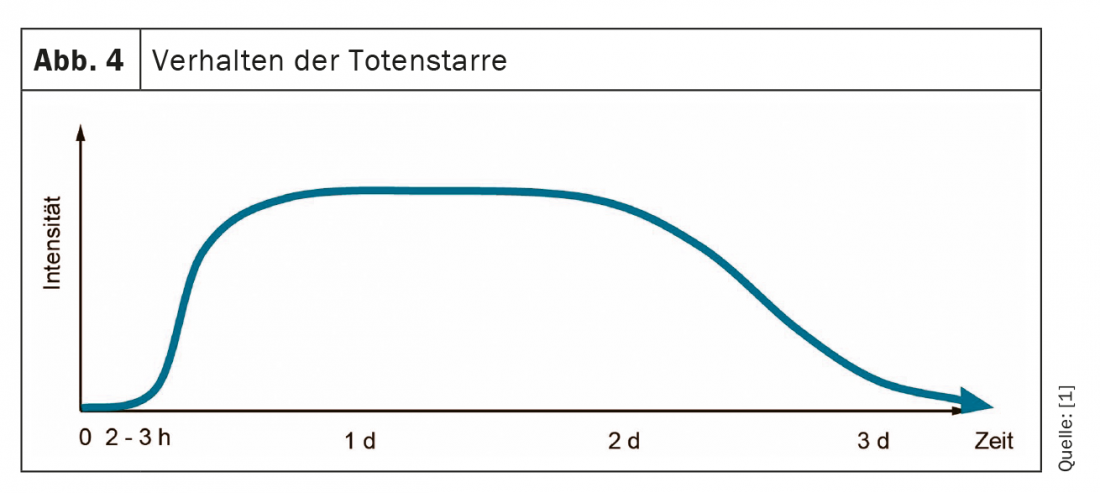

Rigor mortis: Rig or mortis usually occurs about 2-3 hours after death ( Fig. 4) . It is an expression of gradually becoming rigid muscles due to postmortem decay of adenosine triphosphate (ATP) in the muscle. Rigidity occurs only after the muscles have completely relaxed. Therefore, after death, the body first aligns itself with its base and then freezes in this position. At first, usually only a slight stiffness is noticeable in the joints during passive movement, then a progressively increasing rigidity that becomes completely pronounced in all body joints after about 8 hours. After that, overcoming the rigidity is only possible with a great deal of force. After about 2-3 days, the rigidity dissolves by proteolysis.

It remains to be noted here that the occurrence, progression, and resolution of rigor mortis are strongly temperature dependent. At low ambient temperature the process slows down and at high temperature the process accelerates. Likewise, rigor mortis occurs more rapidly after muscle work with ATP loss, e.g. in the legs when dying while cycling or jogging. In the case of corpses from flowing water, rigor mortis may not develop because the corpse is constantly moving and the incipient rigor mortis is permanently broken.

Putrefaction: Putrefaction refers to the anaerobic decomposition of tissue by bacterial enzymes with the development of typical, foul-smelling gases. The red blood pigment hemoglobin is converted into sulfhemoglobin (green). The bacteria usually originate from the colon or the mouth-nose area. Accordingly, putrefaction begins either in the colon (common) or in the face (less common). The earliest sign of decay is a green discoloration of the skin, usually on the right lower abdomen, because this is where the colon is closest to the abdominal skin. Caution: Distinguishing this green discoloration from a hematoma is often not easy. The putrefaction progresses along the vascular network, the skin vessels stand out blackish (so-called “puncturing vein network”), the whole skin turns green-black, the gas pressure inflates the body, blistering of the skin occurs and reddish-brownish, foul-smelling liquid is discharged from the mouth and nose. The development of rot is strongly temperature-dependent; in summer, it may be clearly visible after just one day.

To be distinguished from putrefaction are the following cadaveric changes:

Mummification: tissue preservation by water loss; desiccation. Begins in dry environments after only a few days on the fingers, tip of the nose, lips and scrotum in the form of a dark discoloration and leathery change in the skin. After months, the whole body may be mummified.

Skeletonization: exposure of bones by tissue decay and/or animal scavenging. In the forest, complete skeletonization by insects etc. may be possible within two weeks.

Fat wax formation (adipocire): Tissue preservation by hydrogenation of unsaturated fatty acids with transformation of body fat in a moist, oxygen-poor environment (water, moist clay grave, etc.) into a white-gray, greasy, partly crumbly to lime-hard mass. Duration: months to years.

Further specialized medical examinations

In the following, some further examinations are listed, which are carried out or examined after a death has been reported as agT on the occasion of the so-called legal inspection (special medical examination by a forensic physician or district or county physician) for a closer estimation of the time of death. However, these examinations are no longer part of the medical postmortem.

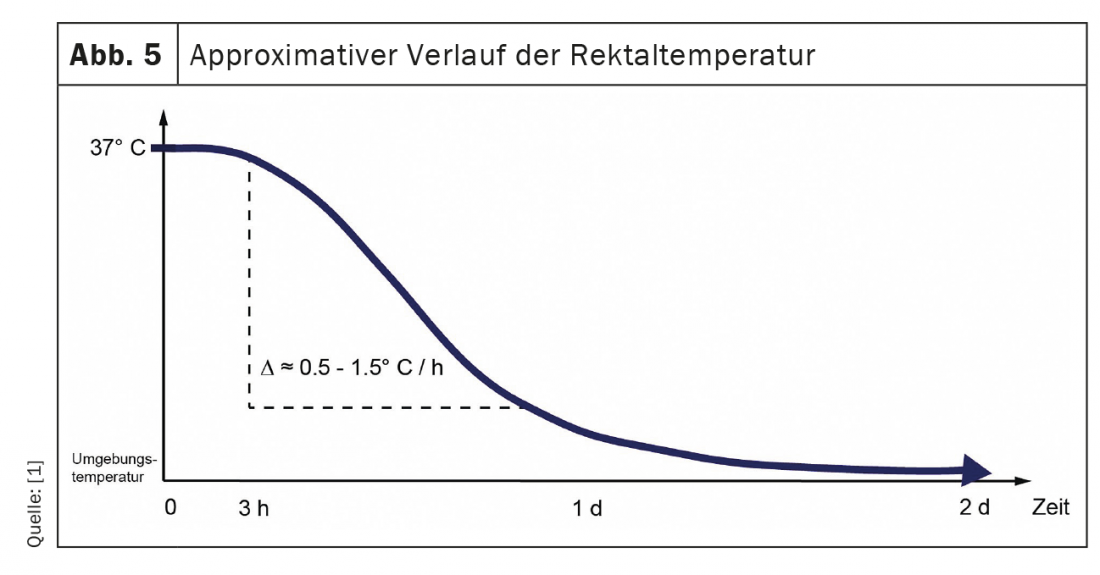

Cooling down (or adaptation of the body temperature): By suspending the metabolism, the body temperature gradually adapts to the ambient temperature. In Central European regions (ambient temperature usually <37 °C), this usually means that the body cools down. This cooling curve is not linear, but sigmoidal (Fig. 5) and depends, among other things, on the outside temperature, the fullness of the body, the clothing and the temperature. coverage, air movement and humidity. In the first two hours after death, there is virtually no cooling (plateau phase), followed by a somewhat steeper drop of about 0.5-1.5 °C per hour to about 27 °C, after which there is a flatter drop until the temperature equals the ambient temperature.

To get the most accurate approximation of core body temperature, forensic medicine usually measures rectal temperature on the corpse. For this purpose, a suitable thermometer (not a thermometer!) should be inserted rectally to at least approx. 8 cm from ano. In addition, the ambient temperature resp. Water temperature (for floaters) to be measured.

Muscle responses to mechanical, chemical, or electrical stimulus:

- Impact on e.g. M. Biceps brachii with heavy reflex hammer, metal rod or similar: Triggering of a contraction of the whole muscle up to approx. 1.5-2.5 h post mortem, then a local muscle contraction (so-called idiomuscular bulge) up to approx. 8-12 h post mortem.

- Defined electrical stimulation of facial mimic muscles: response up to about 20 hr post mortem.

- Instillation of miotica or mydriatica into the eye: subsequent pupillary reaction until about 24 hours post mortem.

Take-Home Messages

- The mere absence of injury is not an indication of natural death.

- The opinion that only deaths where a crime is suspected must be reported is wrong.

- The entire surface of the body must be inspected during the postmortem examination.

- As soon as a death is determined to be agT after any resuscitation measures have been taken and death has been determined with certainty, any manipulation of the corpse and the place where the corpse was found that goes beyond the determination of death must be refrained from in order to protect traces.

- In order to establish death with certainty, especially in the case of death outside the hospital, there must also be certain signs of death (death marks, rigor mortis, decomposition or injuries incompatible with life).

Literature:

- Skriptum Rechtsmedizin, Institute of Forensic Medicine, University of Bern, 13th revised and supplemented edition 2020; digital: www.irm.unibe.ch: Study Downloads Skriptum Rechtsmedizin.

- Merkblatt ärztliche Leichenschau, Institute of Forensic Medicine, University of Bern; digital: www.irm.unibe.ch/unibe/portal/fak_medizin/ber_dlb/inst_remed/content/e99473/e99476/e141288/section141293/files141719/MerkblattLeichenschau_de2015_ger.pdf

HAUSARZT PRAXIS 2021; 16(3): 12-16

CARDIOVASC 2021; 20(3): 24-27