Classic evidence-based recommendations for the treatment of psoriatic arthritis often prove difficult. The reason: Due to the strong heterogeneity of the disease and the study designs often borrowed from RA, their endpoints are hardly suitable as a basis for an individual therapy decision. A team of researchers has evaluated studies on the effect and use of the various substances and provides tips on how to find the best therapeutic strategy.

Therapy selection for psoriatic arthritis (PsA) must be individualized according to the manifestation pattern and other factors such as comorbidities, social factors, mode of application, and concomitant diseases. Therapeutic strategies approved for PsA include the use of NSAIDs, csDMARDs, biologics (TNF inhibitors, IL-12/23 and IL-17 inhibitors, T-cell modulators), and tsDMARDs (PDE4 inhibition, JAK inhibition). Recent studies of the pathophysiological processes in the disease process of PsA have been able to identify additional targets besides TNF inhibitors, whose inhibition effectively modifies the disease process of PsA and psoriasis.

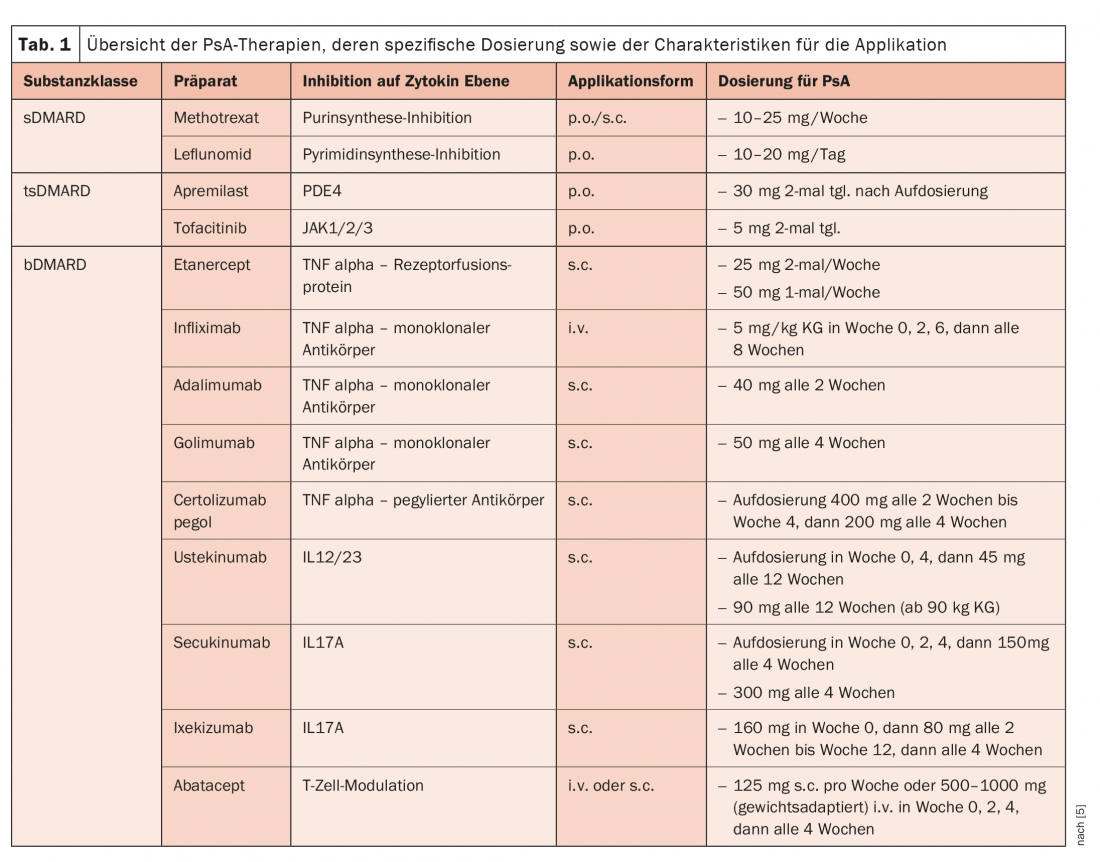

Three international therapy recommendations of the American College of Rheumatology (ACR), the European League Against Rheumatism (EULAR), and the Group for Research and Assessment of Psoriasis and Psoriatic Arthritis (GRAPPA) essentially provide orientation, write Dr. Michaela Köhm from the Department of Rheumatology at Goethe University Frankfurt/Main (D) and her colleagues [1]. The use of non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) continues to be recommended here as first-line therapy for PsA treatment, which can be used at symptom onset but also before diagnosis is confirmed. In everyday care, attention must be paid to substance-specific gastrointestinal, cardiovascular, and renal risks. Systemic glucocorticoids (GC), on the other hand, play only a minor role in PsA. However, intra-articular injection may be considered for the treatment of mono- or oligoarticular patterns of involvement or as an adjunct to existing therapy with disease-modifying antirheumatic therapies (DMARDs). DMARDs are used after a confirmed diagnosis has been made and when symptoms persist (Table 1) .

Leflunomide good csDMARD alternative

The most commonly administered conventional synthetic DMARD (csDMARD) in PsA therapy is methotrexate (MTX). However, no clear study data are available regarding its effectiveness, the researchers note: In the MIPA trial, there was no significant improvement compared with placebo in most of the efficacy parameters measured, whereas in the subanalysis of the open-label TICOPA trial, the efficacy of MTX at relatively high doses (25 mg per week) has been demonstrated in PsA patients. Alternative to MTX is leflunomide, whose level of evidence for efficacy in the treatment of PsA compared with MTX has been demonstrated in studies. In practical use, it is mainly used in the treatment of musculoskeletal involvement outside the axial skeleton, as leflunomide shows limited efficacy on skin involvement.

Sulfasalazine has been shown to have only moderate efficacy on affected joints with no effect on skin involvement, so it is classified only as a backup medication, while ciclosporin’s safety profile limits its use in patients with reduced liver or kidney function. It is true for all csDMARD therapies that they show clinical effectiveness in the treatment of peripheral arthritis but are insufficiently applicable for the treatment in the presence of enthesitis in particular, but also partly in dactylitis, the authors explain. For the treatment of an axial manifestation of PsA, all csDMARDs are unsuitable as treatment options.

Recent analyses show that apremilast (APR) may be an alternative therapy after csDMARD failure in moderate PsA. The phosphodiesterase-4 inhibitor is approved for psoriasis and PsA and, in the latter case, can be used both as monotherapy and in combination with MTX or other csDMARDs. Studies have demonstrated efficacy on both skin and musculoskeletal infestations.

The oral JAK inhibitor tofacitinib is approved for the treatment of PsA exclusively in combination with csDMARD and also shows a good response in a controlled trial after TNF failure. Therapy is also effective in the axial manifestation of PsA. In addition, the compound was similarly effective after failure of prior TNF inhibition.

Secukinumab strongest against psoriasis

Biologic DMARDs such as the TNF-alpha inhibitors etanercept, infliximab, adalimumab, and golimumab have been shown to be effective on both cutaneous and musculoskeletal clinical manifestations, including axial manifestations (with etanercept having lower effectiveness on cutaneous psoriasis). Except for golimumab, all substances in this group are approved for the treatment of both psoriasis and PsA. Attention should be paid to the different (higher) dosage of individual substances for psoriasis therapy, remind the authors.

Ustekinumab is an IL-12/23 inhibitor initially developed for the treatment of psoriasis. In terms of potency, it was shown to be superior to anti-TNF therapy in psoriasis vulgaris. Studies on PsA therapy showed superiority compared to the placebo group. Significant improvement in quality of life and function was also observed after csDMARD or biologics pre-therapy in addition to improvement in disease activity. Secukinumab is an inhibitor IL-17A. Of all the approved substances, it shows the strongest effect on psoriasis. Secukinumab is also approved for the treatment of ankylosing spondylitis. Ixekizumab significantly improved skin florescence with near normalization of skin texture in the treatment group after only 6 weeks of therapy. For the anti-IL17A monoclonal antibody, a rapid reduction in itching and an improvement in quality of life were also described. Abatacept as a T-cell modulating therapy shows the highest efficacy on polyarticular manifestations in PsA treatment. In contrast, effectiveness on other manifestations of PsA is limited.

Involve the patient

Although patients are easily identified as at risk for musculoskeletal inflammation by their initial psoriatic disease, it often takes months before referral to a rheumatologist is made and targeted therapy is initiated to control inflammation. A multistep approach should be taken in selecting the individually appropriate treatment regimen, recommend Köhm et al. In addition to the clinical phenotypic characterization of the patient, potential concomitant diseases, long-term safety aspects, contraindications, and the patient’s wishes, among others, also influence the choice of drug. All these factors should be worked through and taken into account step by step.

The most effective therapies for the treatment of arthritis are considered to be the TNF inhibitors, the IL-17 inhibitors, and also tofacitinib; ustekinumab at the low dose of 45 mg every 3 months and apremilast appear to be somewhat less effective. Leflunomide vs. placebo showed a significant demonstrable effect on peripheral arthritis in PsA in one RCT, with less evidence for MTX. All biologics therapies have shown efficacy against enthesitis, and the same is true for apremilast and tofacitinib in this manifestation. The authors do not consider conventional basic therapeutics as first-line agents in this case. The same applies to dactylitis as to enthesitis, but here the conventional basic therapeutics are partially effective. Conventional basic therapeutics have been shown to be ineffective in spondyloarthritis. A good body of data in ankylosing spondylitis exists for TNF inhibitors and IL-17 inhibitors, whereas selective IL-23 inhibitors have no effects in this indication.

When deciding on the form of application, the patient and his or her wishes should always be included in the treatment decision (shared decision). Biologics are to be administered parenterally (i.v. or s.c.), whereas conventional basic therapeutics are administered orally, as are tsDMARDs such as apremilast and tofacitinib. In addition, there are differences in the application frequency/interval.

Literature:

- Köhm M, Burkhardt H, Behrens F: Therapeutic strategies of psoriatic arthritis. DMW – Deutsche Medizinische Wochenschrift 2020; 145(11): 773-780; doi:10.1055/a-0964-0231.

InFo PAIN & GERIATry 2020; 2(2): 21-22.