Pulmonary involvement in the setting of inflammatory rheumatic systemic disease is a relatively common manifestation that requires appropriate awareness by both pulmonologists and rheumatologists and, ideally, interdisciplinary management of such cases. Various parenchymatous lung pathologies can be found, with granulomatous changes as a subgroup among them.

Pulmonary involvement in the setting of inflammatory rheumatic systemic disease is a relatively common manifestation that requires appropriate awareness by both pulmonologists and rheumatologists and, ideally, interdisciplinary management of such cases. Various parenchymatous lung pathologies can be found, with granulomatous changes as a subgroup among them. Granuloma refers to a nodular circumscribed collection of inflammatory cells in tissue, classically macrophages but also granulocytes or lymphocytes. Histologic evidence of granulomatous lung disease requires workup of several rheumatologic differential diagnoses. The aim of this article is to provide an overview of granulomatous lung diseases from the rheumatologic specialty with the exception of sarcoidosis. The focus is on diagnostics and, above all, therapy.

ANCA-associated vasculitides

ANCA-associated vasculitides are the first to be considered. This group of small vessel vasculitis includes three entities: Granulomatosis with polyangiitis (GPA), microscopic polyangiitis (MPA), and eosinophilic granulomatosis with polyangiitis (EGPA), with no granuloma formation histologically in MPA.

Granulomatosis with polyangiitis (GPA), clinical picture

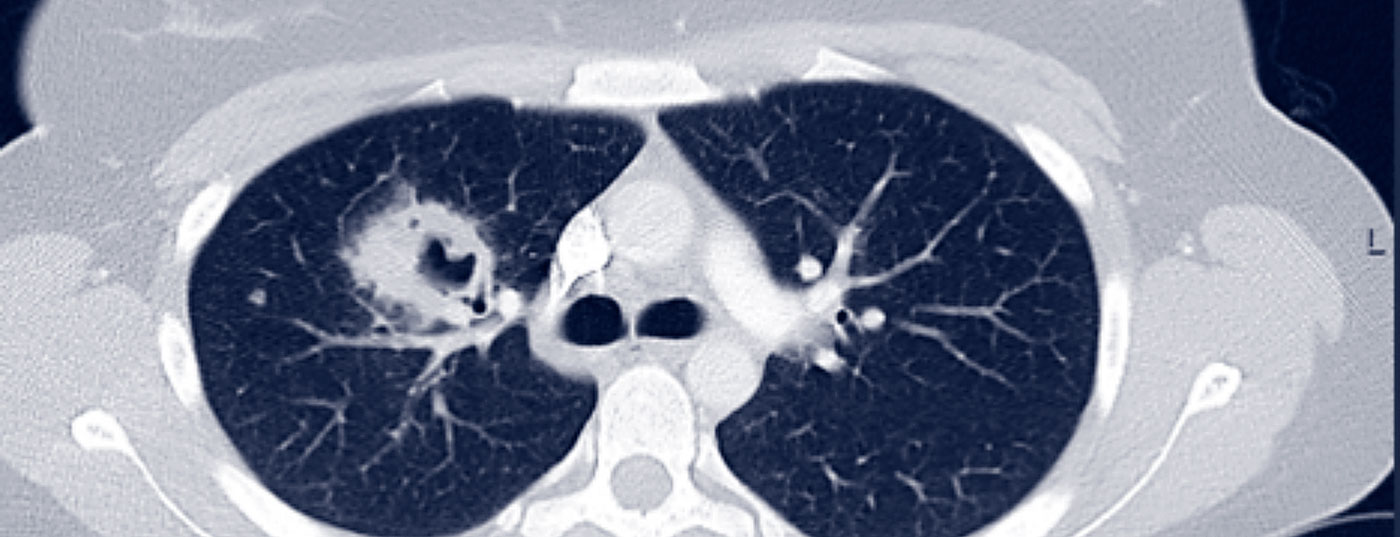

GPA may initially be oligosymptomatic (localized stage of the disease). Involvement of the nasopharynx in the sense of chronic sinusitis or rhinitis is typical at first. With pulmonary involvement, GPA is already classified as a generalized disease, so accompanying clinical symptoms (B symptoms, myalgias, arthralgias, rash, arthritis) and paraclinical symptoms (CRP and ESR elevation, anemia, leukocytosis, thrombocytosis) are typically to be expected. Pulmonary involvement is possible in the form of pulmonary nodules, infiltrates, pulmonary fibrosis, cavities, or even alveolar hemorrhage (Fig. 1).

ANCA diagnostics

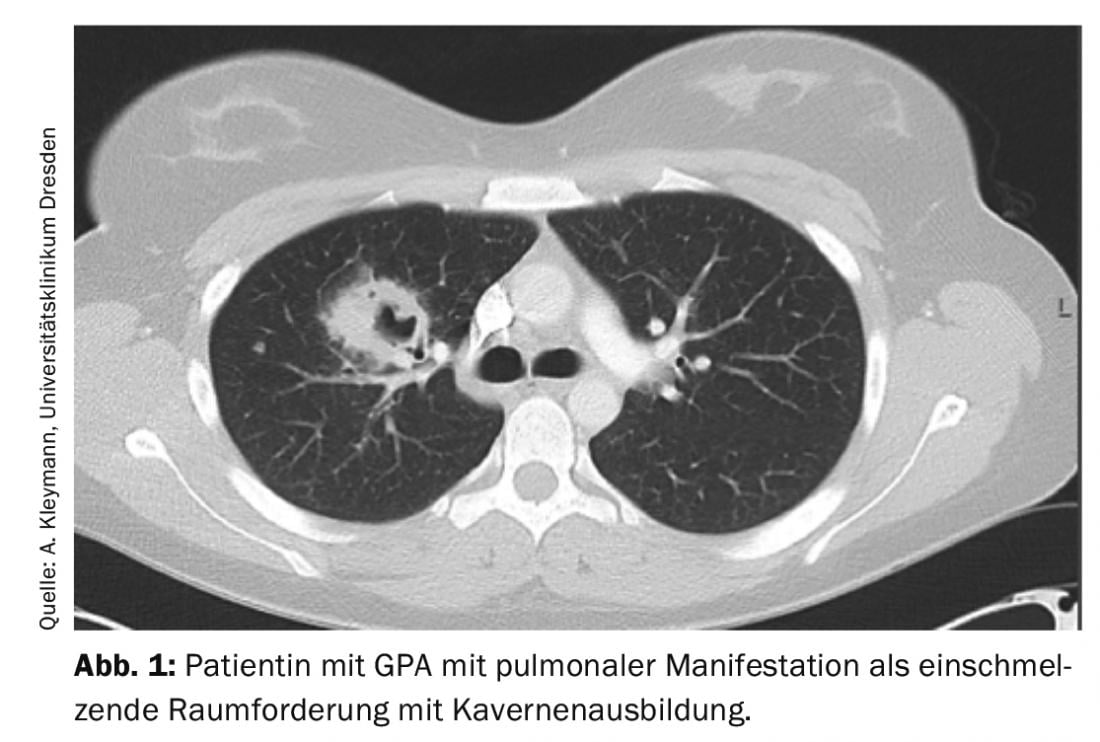

An important part of the diagnosis is the determination of ANCA (antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibodies) with autoantibodies directed against proteinase-3 and myeloperoxidase. ANCA were first described in glomerulonephritis in 1982 and were initially judged to be virus-associated. It was not until 1985 that the description occurred in GPA patients. Initially, determination by indirect immunofluorescence is recommended as the gold standard. The results are to be classified according to fluorescence pattern and titer. pANCA is a perinuclear fluorescence pattern, cANCA is a cytoplasmic pattern (Fig. 2). Sometimes the fluorescence pattern is reported as xANCA, assuming nonspecific ANCA, e.g. in the context of ulcerative colitis.

The specificity of positive ANCA results is only increased by the detection of autoantibodies against corresponding target antigens, in the case of pANCA against myeloperoxidase and in the case of cANCA against proteinase-3. Their determination is usually performed by ELISA (enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay). If ANCA-associated vasculitis is suspected, structured screening for possible other organ manifestations should be initiated. In particular, renal involvement in the form of Pauci-immune glomerulonephritis should be considered. Therefore, in addition to retention parameters (creatinine, urine volume, GFR), a urine sediment should be requested without exception. If there is erythrocyturia, proteinuria, or evidence of hyaline cylinders, urine microscopy with a question about dysmorphic erythrocytes in terms of active nephritic sediment and protein quantification should be ordered. If there is a confirmed suspicion of renal manifestation, a renal biopsy is necessary. This often allows not only to confirm the diagnosis, but also to determine the prognosis regarding kidney function. In obese patients or at increased risk of bleeding, transjugular renal biopsy is a reasonable alternative to transcutaneous biopsy.

Therapy

After diagnosis, if there is a pulmonary manifestation of vasculitis, induction therapy with cyclophosphamide or rituximab is usually indicated concomitantly with corticosteroids, with relatively rapid reduction of corticosteroids to a dose of 7.5-10 mg/d prednisolone equivalent after 3 months. The exception to this is an isolated manifestation with small, nondecaying pulmonary nodules without functional limitation, where baseline therapy with methotrexate, provided there is no renal impairment, or azathioprine is also possible without prior induction therapy.

Cyclophosphamide induction should be favored over oral administration as an i.v. bolus based on data from the CYCLOPS trial due to low adverse event rates [1]. The standard dosage is 15 mg/kg body weight, with the first 3 administrations every 2 weeks, then every 3 weeks. The dose should be adjusted according to age and renal function (reduction to 12.5 mg/kgKG in 60-70-year-olds if creatinine up to 300 µmol/l, to 10 mg/kgKG in creatinine >300 µmol/l and in >70-year-olds if creatinine up to 300 µmol/l, and to 7.5 mg/kgKG in >70-year-olds with creatinine >300 µmol/l). In most cases, 6 boluses are sufficient. Under cyclophosphamide therapy, in addition to gonadal and urinary bladder toxicity (therefore, administration of 2-mercaptoethanesulfonatsodium (MESNA) is also recommended), the risk of relevant leukopenia should be emphasized. The nadir occurs 10 -12 days after administration, so appropriate blood count monitoring should be done around this time and if necessary further dose adjustment for the next administration (if leukocytes <4 GPT/l dose reduction of cyclophosphamide by 25% and the next administration only when leukocyte count >4 GPT/l). An alternative to cyclophosphamide is induction with the anti-CD20 antibody rituximab. The efficacy of rituximab has been demonstrated in 2 trials (RAVE and RITUXVAS). Here both the regimen with 4× weekly administration of 375 mg/m2 body surface area and 2× 1 g absolute dose at intervals of 14 days are common practice. Prior to initiation of rituximab therapy, hepatitis screening (risk of reactivation of chronic hepatitis B) and ideally updating of vaccination status should be performed, as reduced/insufficient vaccination response can be expected during therapy.

The increased risk of infection with atypical pathogens should not be underestimated with either drug, so Pneumocystis jirovecii prophylaxis is necessary in all patients during induction therapy regardless of the drug chosen (e.g., Cotrim [Trimethoprim/Sulfamethoxazol] 480 mg 1× daily). Prophylaxis can be discontinued after induction is complete and at prednisolone dose <10-15 mg/d. The role of plasmapheresis in severe courses such as diffuse alveolar hemorrhage (DAH) continues to be seen as controversial. Although the European Rheumatology Association (EULAR) recommends considering it in its latest 2016 recommendation, the PEXIVAS trial published in NEJM in February 2020, which included 31 patients with severe DAH in the plasma exchange arm and 30 patients in the study arm without plasmapheresis, showed no survival benefit [2].

After completed induction, maintenance therapy is usually with rituximab (2 doses of 500 mg i.v. at 14-day intervals, followed by 500 mg every 6 months) or alternatively with azathioprine (2 mg/kg body weight) for at least 2 years. Initiation of azathioprine medication initially requires regular laboratory monitoring (blood count and transaminases) and co-medication with xanthine oxidase inhibitors (allopurinol and febuxostat) is contraindicated. In addition, determination of thiopurine S-methyltransferase (TPMT) is recommended in some centers to prevent severe bone marrow suppression in patients with the corresponding enzyme deficiency.

Alternatives in case of contraindication/intolerance are methotrexate (but not in renal involvement with renal insufficiency) or mycophenolate mofetil. It should be emphasized, however, that mycophenolate mofetil is not approved for this purpose and is thus “off-label use” and less effective than azathioprine, even based on data from the IMPROVE trial (hazard ratio for relapse with mycophenolate mofetil vs. azathioprine 1.69) [3]. Blockade of the complement receptor C5a with avacopan represents an interesting new therapeutic approach [4]. In the study presented online at this year’s European Rheumatism Congress EULAR, this orally administered substance showed a comparable effect to the control group with steroids when used concomitantly alongside standard therapy with cyclophosphamide or rituximab but without steroids. Thus, in the future, steroids could be completely eliminated in this disease group with the use of Avacopan.

Eosinophilic granulomatosis with polyangiitis (EGPA)

EGPA is challenging in the group of ANCA-associated vasculitides. Confirmation of the diagnosis is difficult because histology often fails to detect vasculitis, ANCA are not infrequently negative, and a primary hypereosinophilic syndrome must be ruled out as an expression of clonal disease.

A typical pulmonary manifestation is the appearance of volatile infiltrates. Histologically, tissue eosinophilia can often be detected on lung biopsy. The decision on therapy is also not always easy due to insufficient studies. In the absence of unfavorable prognostic parameters such as renal or cardiac involvement, monotherapy with corticosteroids is conceivable; otherwise, cyclophosphamide is available for organ-threatening manifestations or methotrexate and azathioprine for milder courses. Rituximab has a secondary role in EGPA due to insufficient data. Of interest, however, is the use of the IL-5 antagonist mepolizumab, which demonstrated efficacy in a phase 3 study of 136 patients with refractory or relapsed EGPA.

In this study, 4-weekly s.c. Administration of 300 mg mepolizumab for 52 weeks, more patients achieved remission (32% versus 3%) and also reduced the prednisolone dose below 4 mg/d (44% versus 7%). However, even in the mepolizumab group, remission was still not achieved in 47% of cases [5]. Mepolizumab now also has FDA approval for EGPA.

Rheumatism node

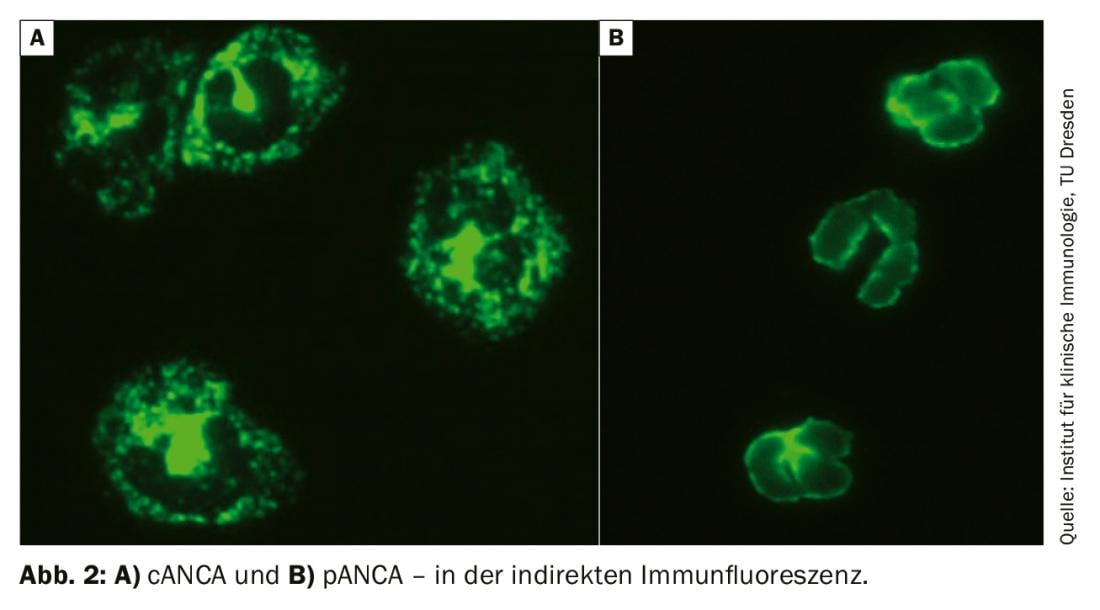

Rheumatoid nodules exhibit another granuloma formation. These are most likely to occur in patients with prolonged seropositive (rheumatoid factor and/or anti-CCP antibody positive) rheumatoid arthritis and cutaneous rheumatoid nodules. Differentiation from malignancy is difficult without histology, since, on the one hand, multiple rheumatoid nodules of progressive size may be present during the course of the disease, and, on the other hand, patients with rheumatoid arthritis per se have a higher risk of malignancy. Typically, pulmonary rheumatic nodules are located subpleurally or in the region of interlobular septa and are usually asymptomatic (Fig. 3).

However, they may also cause pleural effusion, pneumothorax, hemoptysis, or bronchopulmonary fistulae. If rheumatoid nodules are detected, the basic therapy may need to be adjusted, as an increase in the size of rheumatoid nodules is more frequently observed with methotrexate. Cases with development of pulmonary rheumatoid nodules have also been described with leflunomide [6,7].

Atypical infections

In the presence of a granulomatous inflammatory reaction, atypical infections under the more immunosuppressive baseline therapy should also be considered. Infectiologically, fungal infections such as histoplasmosis and sporotrichosis should be considered in addition to tuberculosis. The risk of infection in patients with inflammatory rheumatic systemic diseases is increased both by the underlying disease and by the immunosuppressive basic therapeutics used.

Most importantly, TNF blockers appear to relevantly influence the risk of granulomatous pulmonary infections. This is well understood by the pathophysiological importance of TNF-alpha in defense and granuloma formation against bacterial and fungal pathogens.

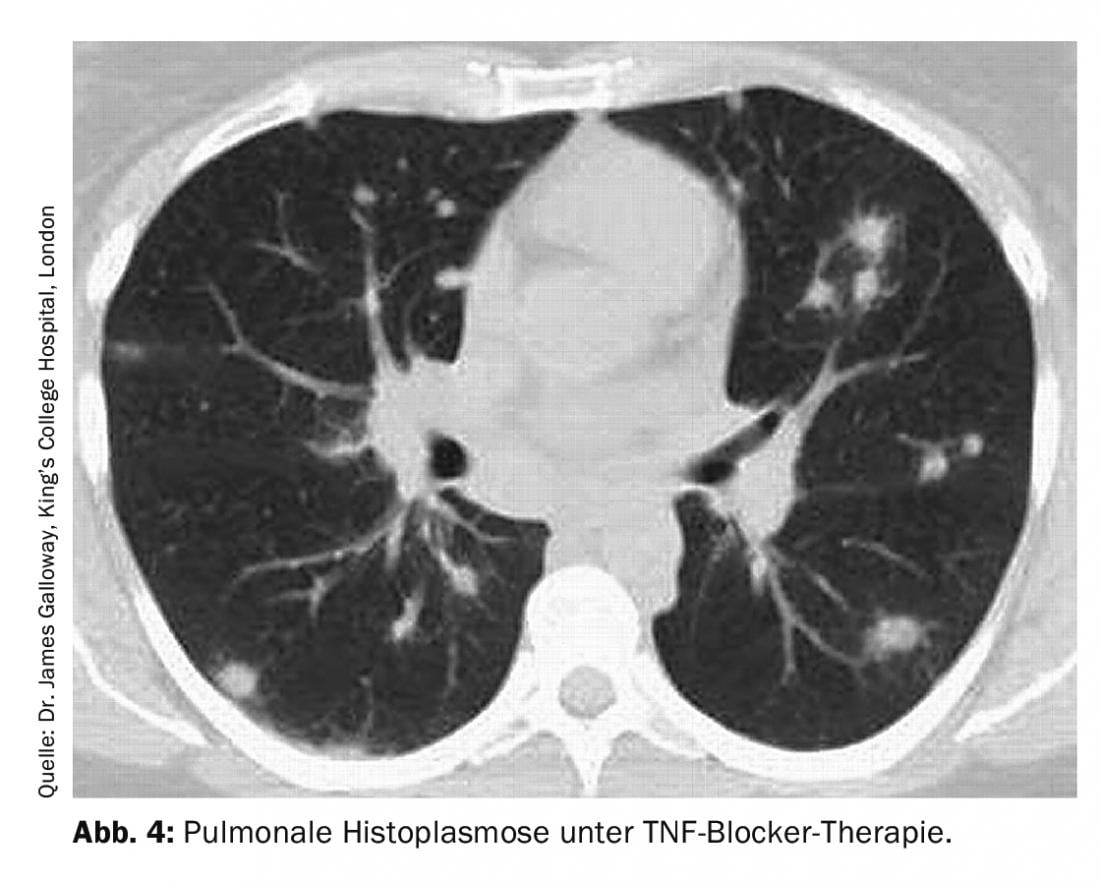

Histoplasmosis

Pulmonary histoplasmosis is caused by Histoplasma capsulatum. This ubiquitous pathogen is found primarily in North and Central America. Clinical differentiation from sarcoidosis and malignancy is often difficult because pulmonary manifestations are manifold (pulmonary infiltarte or round foci, caverns, medistinal lymphadenopathy, or space-occupying lesions) (Fig. 4).

Diagnostically, in addition to serology (histoplasma-specific antibodies and antigen determination), broncho-alveolar lavage with fungal staining and culture, but also the corresponding histological examination of the bioptate for fungi are used. Therapeutically, either no therapy or various antifungal agents are used, depending on the severity of the disease.

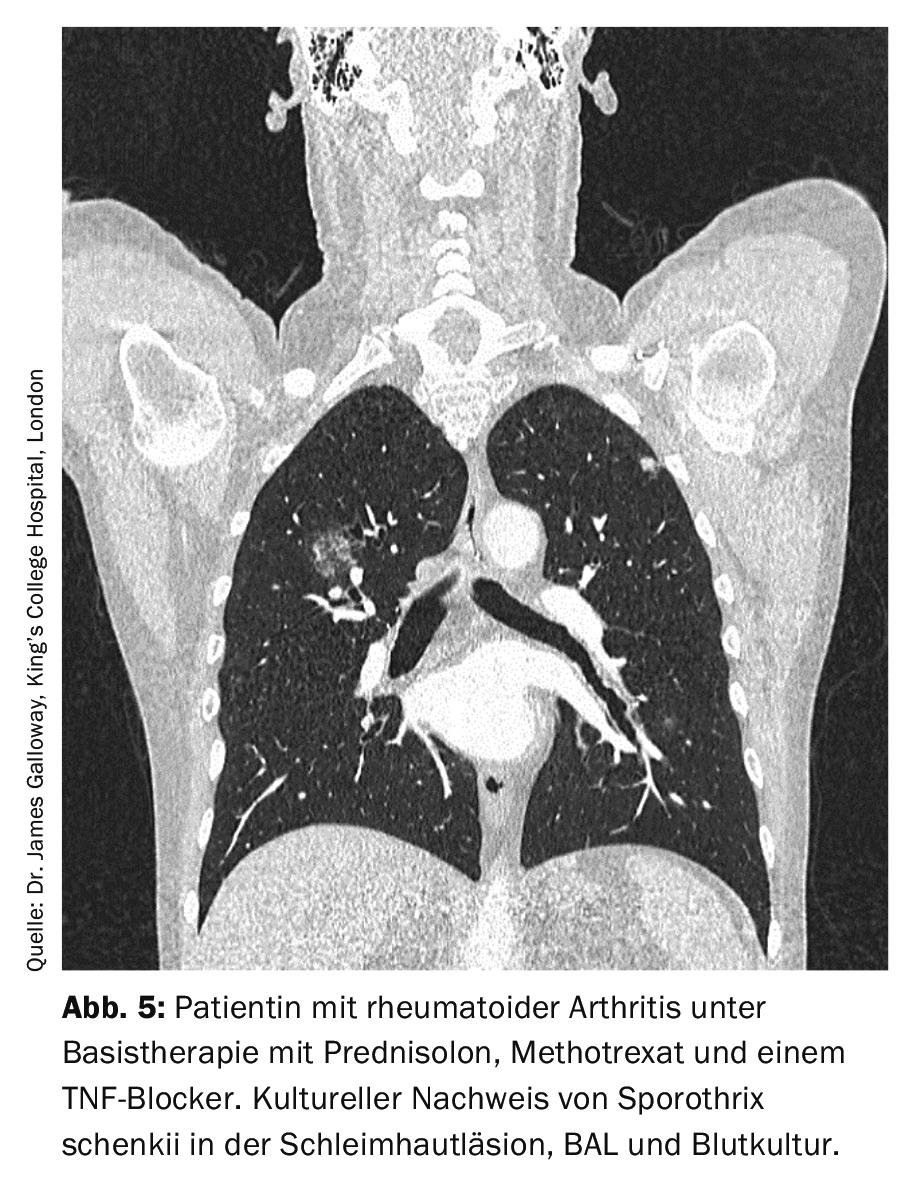

Sporotrichosis

Sporotrichosis is caused by Sporothrix schenckii and classically has a cutaneous manifestation. In pulmonary manifestations, the disease resembles tuberculosis (Fig. 5) . The gold standard of diagnosis is cultural pathogen detection, since histopathology can be falsely negative for a low pathogen count even with appropriate staining, and serologic and PCR testing are currently not routinely available.

If left untreated, pulmonary sporotrichosis is fatal, so antifungal therapy is always required. For mild courses, p.o. Itraconazole 2×200 mg/d can be used. If the manifestation is severe, i.v. amphotericin B is recommended first and a switch to itraconazole is made only as the disease progresses. The duration of therapy should be at least 1 year [8].

Primary immunodeficiencies

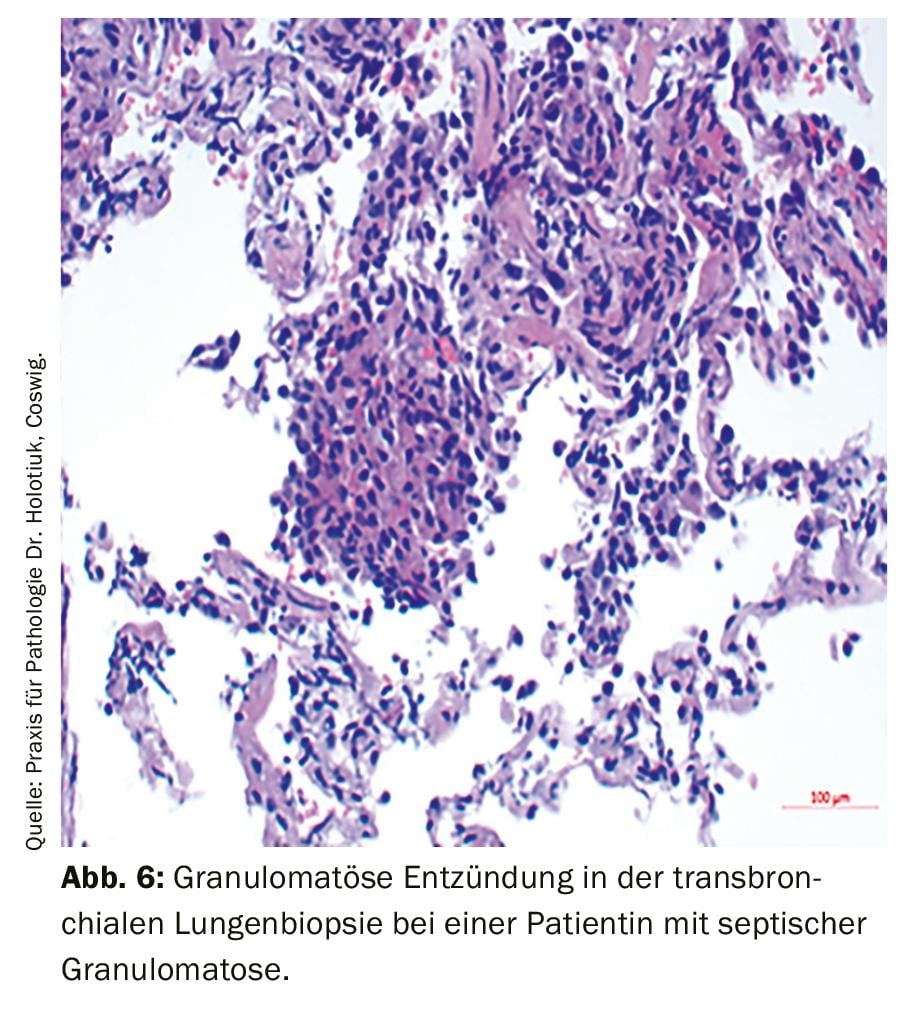

Lastly, the complex group of primary immunodeficiencies should be mentioned. In particular, patients with recurrent infections and autoimmune phenomena should also be considered for this differential diagnosis. The acronym ELVIS describes the pathological susceptibility to infection (atypical pathogens and localizations, protracted course, exceptional intensity and number of infections [Summe]). The acronym GARFIELD summarizes the possible manifestations as an expression of a disturbance of the immune regulation: Granulomas (Fig. 6), autoimmune phenomena, recurrent fever, eczematous skin lesions, lymphoproliferation (lymphadenopathy, splenomegaly) and chronic intestinal inflammation [9]. In case of a justified suspicion, further diagnostics with a cellular (differential blood count, lymphocyte typing) and a humoral immune status (immunoglobulin determination, if necessary also with IgG subclasses, complement factors) should be initiated and a corresponding clarification by a physician experienced in immunodeficiency diagnostics and treatment should be initiated.

Take-Home Messages

- In case of granulomatous lung changes, rheumatologic diseases such as small vessel vasculitis, rheumatoid nodules, and also atypical infections under basic therapeutics and primary immunodeficiencies with autoimmune phenomena should also be considered.

- If pulmonary vasculitis is suspected, initiate ANCA diagnostics with determination of antibodies against proteinase 3 and myeloperoxidase and, if the diagnosis is confirmed, initiate adequate immunosuppression promptly.

- Pulmonary rheumatoid nodules are not uncommon in seropositive rheumatoid arthritis, but are often difficult to distinguish from malignancies at initial manifestation

- Atypical pulmonary infections should be considered especially in patients treated with biologics and/or with high-dose steroids.

- Primary immunodeficiencies occur frequently with autoimmune phenomena and should therefore also be excluded if there is a reasonable suspicion.

Literature:

- de Groot K, Harper L, Jayne DR, et al: Pulse versus daily oral cyclophosphamide for induction of remission in antineutrophil cyto-plasmic antibody-associated vasculitis: a randomized trial. Ann Intern Med 2009; 150(10): 670-680.

- Walsh M, et al: Plasma Exchange and Glucocorticoids in Severe ANCA-Associated Vasculitis. N Engl J Med 2020; 382: 622-631.

- Hiemstra TF, Walsh M, Mahr A, et al: Mycophenolate mofetil vs azathioprine for remission maintenance in antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibody-associated vasculitis: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA 2010; 304(21): 2381-2388.

- Merkel PA, Jayne DR, Wang C, et al: Evaluation of the Safety and Efficacy of Avacopan, a C5a Receptor Inhibitor, in Patients With Antineutrophil Cytoplasmic Antibody-Associated Vasculitis Treated Concomitantly With Rituximab or Cyclophosphamide/Azathioprine: Protocol for a Randomized, Double-Blind, Active-Controlled, Phase 3 Trial. JMIR Res Protoc 2020; 9(4): e16664.

- Wechsler ME, Akuthota P, Jayne D, et al: Mepolizumab or placebo for eosinophilic granulomatosis with polyangiitis. N Engl J Med 2017; 376(20): 1921-1932.

- Horvath IF, Szanto A, Csiki Z, et al: Intrapulmonary rheumatoid nodules in a patient with long-standing rheumatoid arthritis treated with leflunomide. Pathol Oncol Res 2008; 14(1): 101-104.

- Rozin A, Yigla M, Guralnik L, et al: Rheumatoid lung nodulosis and osteopathy associated with leflunomide therapy. Clin Rheumatol 2006; 25(3): 384-388.

- Kauffman CA, Bustamante B, Chapman SW, et al: Clinical practice guidelines for the management of sporotrichosis: 2007 update by the Infectious Diseases Society of America. Clin Infect Dis 2007; 45(10): 1255-1265.

- AWMF guideline “Diagnostics for the presence of a primary immunodeficiency” Status: 31.10.2017, valid until 31.10.2020.

InFo PNEUMOLOGY & ALLERGOLOGY 2020; 2(3): 12-16.