The diagnosis of irritable bowel syndrome is based on ROM IV criteria and limited diagnostic workup. The gut-brain axis is one of the recognized etiopathogenetic concepts of this complex multifactorial disorder. Interactions of the autonomic and central nervous systems play an important role. A careful differential diagnosis is critical. Therapy is individual and symptom-oriented.

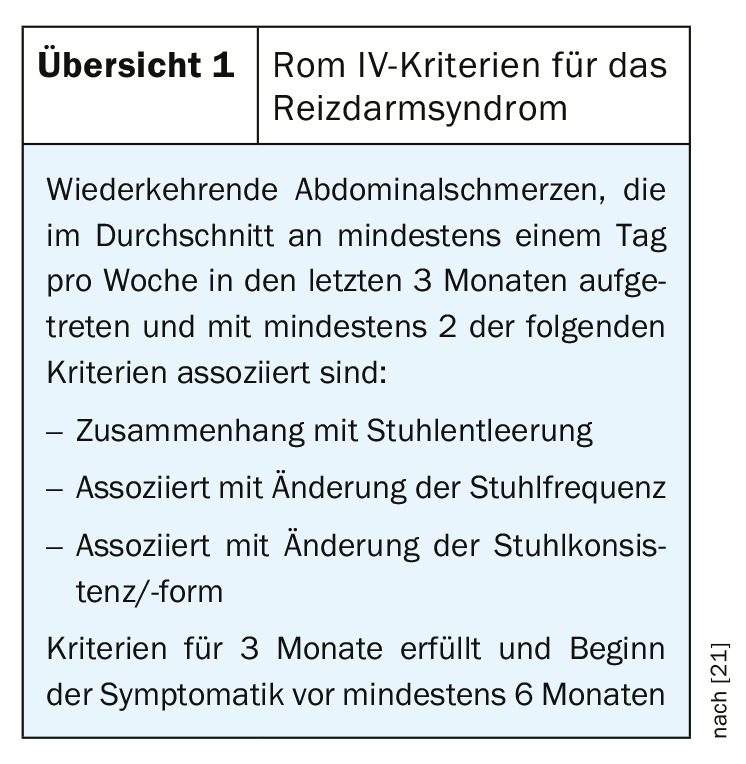

The term irritable bowel syndrome (IBS) subsumes non-specific functional bowel disorders. It is a complex multifactorial disease, and the etiological and pathophysiological relationships have not yet been fully elucidated. The diagnosis of IBS is based on the Rome IV criteria (Overview 1) and on gastroenterological investigations including psychosocial history. IBS is the most common functional disorder of the gastrointestinal tract with an estimated prevalence of 7-30% in Europe [1]. Depending on the stool consistency, the following three subtypes are described: Diarrhea-type IBS (IBS-D), Obstipation-type IBS (IBS-O), Mixed-type IBS (IBS-M). Affected individuals suffer impaired quality of life and there are significant indirect and direct health economic costs associated with it. The prevalence of depressive disorders is significantly higher compared to the general population [2].

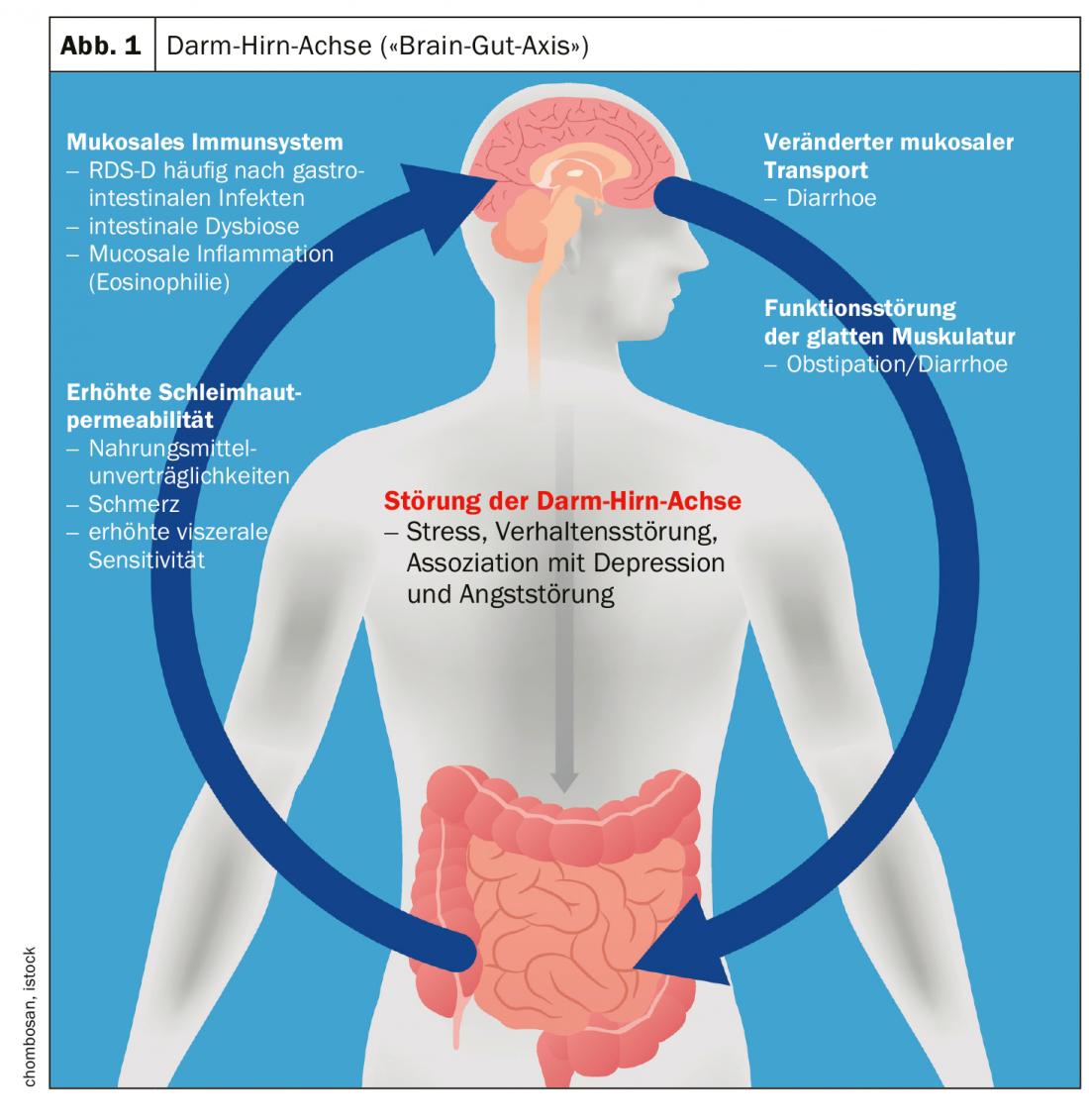

Gut-brain axis as a component of multifactorial etiopathogenesis.

Various pathogenetic factors for IBS and other functional gastrointestinal complaints are discussed. Among other factors, the mechanism of visceral hypersensitivity, i.e., increased vigilance to specific sensations in the gastrointestinal tract, is thought to play an important role [3,4]. Perceptual and pain thresholds to intestinal stimuli are lower in IBS patients, which may contribute to central nervous sensitization [5]. The human digestive tract is an extremely sensitive system that is highly innervated. Innumerable afferent nerve fibers generate information regarding intestinal contents and regulatory processes of digestion, absorption as well as immune defense [6].

Evidence suggests that in RDS, both the central processing of this information and the response to intestinal signals are impaired [7]. These mechanisms play out within the gut-brain axis (“brain-gut axis”), which is a concept for the interaction of the autonomic, neuroendocrine, and neuroimmunological systems with the central nervous system [8] (Fig. 1) . This explanatory model also includes psychosocial factors (e.g., stress processing). In the forthcoming revised version of the S3 guideline “Irritable Bowel Syndrome”, the role of the microbiome is discussed in detail in the chapter on pathophysiology [9]. The complexity of the disease is reflected, among other things, in the fact that the same correlations are not detectable in all affected individuals. Some clusters of processes associated with the pathophysiology of IBS are shown in Figure 1.

Criteria-guided differential diagnostics

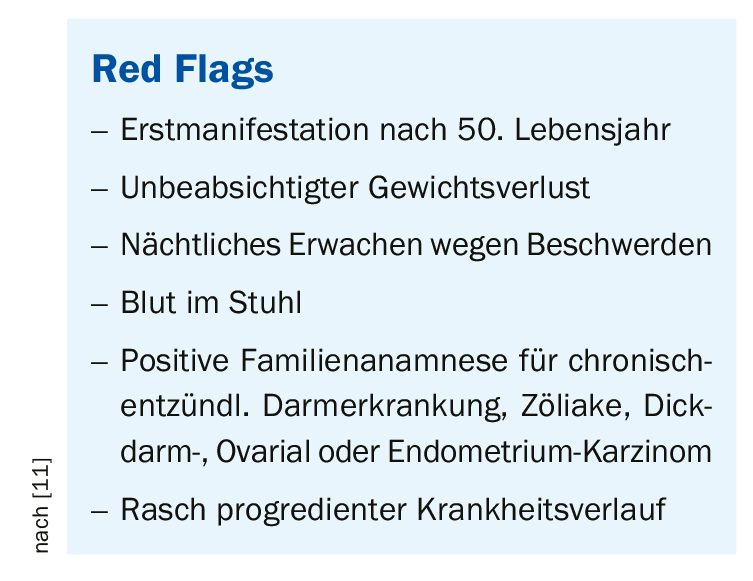

The diagnosis of irritable bowel syndrome is possible based on limited diagnostic testing and using the Rome IV criteria [10,11]. If no alarm signs (box) are present, the diagnosis of IBS can be made if the Rome criteria are met [12]. If alarm signs are present, extended diagnostics are recommended. The exclusion of relevant systemic diseases is particularly important in the first year after the onset of IBS symptoms, with organic disease being identified in only 5% of all patients with IBS [13]. The likelihood of colon cancer after a presumptive diagnosis of IBS is 1% after the age of 50, which is significantly higher than the average for the general population. American guidelines recommend colonoscopy in patients older than 50 years, and European guidelines recommend colonoscopy in RDS-D even before 50 years of age [14,22].

In women, ovarian cancer should always be considered, as this is often associated with IBS-like symptoms [15]. Serologic celiac disease exclusion testing including determination of transglutaminase IgA and total IgA antibodies is recommended in patients with RDS-D, as it has been shown that the prevalence of IgA deficiency in celiac disease is 1.7-3%, significantly higher than in the general population (0.2%) [16]. For differential diagnosis of inflammatory bowel disease, calprotectin should be determined in the stool. If the calprotectin level is <40 µg/g, the risk of inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) is less than 1% [17]. New additions to the relevant topics in the revised version of the S3 guidelines are gluten sensitivity and histamine intolerance. Negative recommendations exist for scientifically unestablished IgG-based tests for food intolerances. Warned against unnecessary and problematic elimination diets, also advised against analysis for dysbiosis in the stool [10].

Individual and symptom-oriented therapy

In the new S3 guideline [9], the aspect of nutrition is given a higher therapeutic priority. A low-FODMAP diet is advised as a possible measure, and prebiotics and probiotics also receive a recommendation. Among symptom-oriented therapies, peppermint oil and tricyclic antidepressants are recommended for pain in addition to spasmolytics, whereas SSRIs are more appropriate for concomitant psychological problems. Peppermint oil has been discussed for years as an effective and well-tolerated natural remedy for patients with irritable bowel syndrome. Convincing evidence of efficacy was provided by a meta-analysis by Khanna and colleagues [18]. Five randomized placebo-controlled trials showed an overall improvement in irritable bowel symptoms with the use of peppermint oil. In particular, abdominal pain improved significantly. The American College of Gastroenterology Task Force recognizes peppermint oil as superior to placebo-only treatment for irritable bowel syndrome [19]. In addition to a proven short-term efficacy of the therapy, the tolerability is also good [20]. Peppermint oil interacts with calcium channels in the intestine, where it prevents calcium from flowing into smooth muscle cells. Relaxation of the bowel occurs, resulting in decreased motility and concomitant reduction of pain symptoms [20]. In addition, peppermint oil has anti-inflammatory and antibacterial properties [20].

Literature:

- Saha L: World J Gastroenterol 2014; 20(22): 6759-6773.

- Grundmann O, Yoon SL: J Gastroenterol Hepatol 2010;25: 691-699.

- Madisch A, et al: Dtsch Arztebl Int 2018; 115: 222-232.

- Mari A, et al: Adv Ther 2019; 36(5): 1075-1084.

- Soares RLS: World J Gastroenterol 2014; 20(34): 12144-12160.

- Brookes SJH, et al: Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol 2013; 10(5): 286-296.

- Lee YJ, Park KS: World J Gastroenterol 2014; 20(10): 2456-2469.

- Matricon J, et al: Aliment Pharmacol Ther 2012; 36(11-12): 1009-1031.

- DGVS Guideline, currently under revision, www.dgvs.de/wissen-kompakt/leitlinien/dgvs-leitlinien/reizdarmsyndrom, last accessed 06.07.2020

- Lacy BE: Gastroenterology 2016; 150: 1393-1407.

- Lenglinger J: Irritable bowel syndrome. Johannes Lenglinger, MD. FOMF Basel, 29.01.2020.

- Whitehead WE, et al: Expert Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol 2017; 11(4): 281-283.

- El-Serag HB, et al: Aliment Pharmacol Ther 2004; 19(8): 861-870.

- AGA: Gastroenerology 2002; 123(6): 2105-2107.

- Hamilton W, et al: BMJ 2009; 339(7721): 616.

- Burri E, Szabo M: HAUSARZT PRAXIS 2019; 14(1): 11-18.

- Menees SB, et al: Am J Gastroenterol 2015; 110(3): 444-454.

- Khanna R, et al: J Clin Gastroenterol 2014; 48: 505-512.

- Ford AC, et al: Am J Gastroenterol 2014; 109 (1): 2-26.

- Shams EC, et al. : JSM Gastroenterol Hepatol 2015; 3(1): 1036.

- Lacy BE, Patel NK: J Clin Med.2017. Oct 26;6(11).

- Layer P, et al: S3 guideline irritable bowel syndrome. Journal of Gastroenterol 2011; 49(2): 237-293.

- Vanner SJ: Gastroenterology 2016; 150: 1280-1291

FAMILY PRACTICE 2020; 15(9): 23-24