About 40% of those affected have a form of acne that requires treatment. Therapy depends on the severity and individual symptom expression. The current guidelines contain practice-oriented evidence-based recommendations.

Acne vulgaris is a disease of the hair sebaceous gland unit with non-inflammatory comedones and inflammatory papules, pustules and nodules of the skin. On average, acne lesions affect about 70-95% of all adolescents [1]. with only a minority of them requiring medical treatment. Predilection sites are face and upper body. In most cases, spontaneous regression occurs after puberty, but moderate to severe inflammatory acne lesions in particular often leave scars. In 10-40%, the disease persists beyond 25 years of age or even begins at this age range, especially in females [2]. The etiology of acne vulgaris is multifactorial. In addition to a genetic disposition, increased sebum production (seborrhea) and a follicular keratinization disorder (hyperkeratosis) as well as bacterial colonization by Propionibacterium acnes and inflammatory reactions play a role.

Adapt treatment regimen to individual symptomatology

Nodules and cysts can be painful, and scars from acne lesions are often accompanied by emotional distress. Therapy depends on the severity and can be by topical preparations alone or combined with systemic treatment (e.g., antibiotics, azelaic acid, benzoyl peroxide, retinoids).

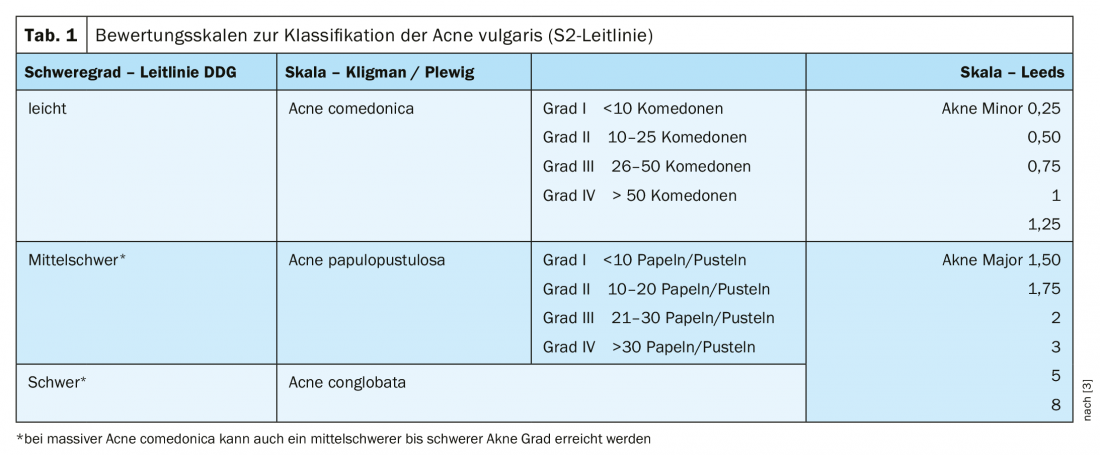

The great variability of the clinical presentation of acne is reflected in the large number of divisions and classifications. However, a standardized clinical assessment is necessary for an adequate severity classification as well as for the documentation of the course of therapy. An overview based on common rating scales can be seen inTable 1 [3]. Patients with mild to moderate acne can be treated with a combination of topical, systemic, and physical therapeutic approaches, with individualized treatment outcomes. The treatment recommendations of the revised European S3 guideline for the treatment of acne are based on a criterion-guided assessment of controlled trials and expert experience [3].

Acne comedonica: The empirical data situation is low, which is why there are no substances with a high recommendation grade here. Fixed combinations do not seem to have any additional benefit here; topical retinoids are the therapy of choice [4].

Acne papulopustulosa: It is considered proven that fixed combinations (adapalene/BPO, clindamycin/BPO or tretinoin/clindamycin) are more effective than the respective mono-substance. Topical antibiotics should be combined with benzoyl peroxide, and combination with a topical retinoid also appears to minimize the development of resistance [5]. Furthermore, treatment with systemic antibiotics should be limited to three months, as continuing treatment beyond this period leads to an increase in the development of resistance and has no additional benefit [6,7]. Systemic antibiotic therapy should also always be combined with topicals (retinoids and/or benzoyl peroxide). Among retinoids, adapalene resulted in less irritation and therefore received a higher recommendation grade than topical isotretinoin/tretinoin [3]. Among systemic antibiotics, doxycycline is the substance of choice. Minocycline has no higher efficacy and is associated with rare but potentially very severe side effects such as “Drug Rash with Eosinophilia and Systemic Symptoms” (DRESS) [8].

In severe inflammatory acne, early use of isotretinoin is recommended [9]. In the S2k guidelines, systemic glucocorticoid therapy is suggested initially to prevent scarring [10]. As an adjunctive treatment for mild to moderate acne, light therapy may be considered (especially blue light), as inflammatory lesions respond better to it than comedones. Regarding photodynamic therapy, there is good evidence of efficacy, but a critical issue is the sometimes severe short-term side effects. With regard to laser medical applications, the empirical evidence base is so far small. The European guideline does not address special cases such as treatment with dapsone or the selection of antiandrogenic hormones; recommendations in this regard can be found in the German S2k guideline, which is still valid [3]. Accompanying pharmacotherapy, manual acne therapy and exfoliation procedures including microdermabrasion are recommended.

Acne tarda: This form of acne is treated essentially like adolescent acne. It is important to rule out endocrinologic disorders (e.g., polycystic ovary syndrome or late manifesting adrenogenital syndrome). It may be possible to achieve a better therapeutic result by early use of isotretinoin.

Post-acne conditions: Scars as well as hypo- and hyperpigmentation and erythema can be treated with surgical procedures, peels, hyaluronic acid augmentation or with lasers. In terms of surgical interventions, punch excision or punch elevation, resolution of scar strictures, and dermabrasion have been particularly successful. For laser medical applications, fractional laser methods are particularly recommended [3].

Acne in pregnancy: topical and systemic retinoids and tetracyclines are contraindicated. Blue light, azelaic acid, BPO, and erythromycin can be used for topical therapy. Systemically, erythromycin and zinc are the therapy of choice; prednisone/prednisolone may also be used for severe cases.

Literature:

- Gollnick H, Zouboulis CC: Not all acne is acne vulgaris. Dtsch Ärztbl 2014. Int111: 301-312.

- Nägeli M, Läuchli S: Acne vulgaris: current insights into pathogenesis and treatment recommendations, Schweiz Med Forum 2017; 17(39): 833-837.

- Nast A, et al: S2k guideline on the treatment of acne. 2010. www.awmf.org

- Degitz K, Falk Ochsendorf A: Acne. JDDG 2017; 15(7): 709-722.

- Jackson JM, et al: A randomized, investigator-blinded trial to assess the antimicrobial efficacy of a benzoyl peroxide 5%/clindamycin phosphate 1% gel compared with a clindamycin phosphate 1.2%/tretinoin 0.025% gel in the topical treatment of acne vulgaris. J Drugs Dermatol 2010; 9: 131-136.

- Dreno B, et al: An expert view on the treatment of acne with systemic antibiotics and/or oral isotretinoin in the light of the new European recommendations. Eur J Dermatol 2006; 16: 565-571.

- Ochsendorf F: Systemic antibiotic therapy of acne vulgaris. J Dtsch Dermatol Ges 2010; 8 (Suppl 1): S31-46.

- Ochsendorf F. Minocycline in acne vulgaris: benefits and risks. Am J Clin Dermatol 2010; 11: 327-341.

- Nast A, Rosumeck S, Erdmann R et al. Methods Report on the Development of the European Evidence-

- based (S3) Guideline for the Treatment of Acne – Update 2016. http://euroderm.org/edf/

- Nast A, Bayerl C, Borelli C et al. [S2k-guideline for therapy of acne]. J Dtsch Dermatol Ges 2010; 8 (Suppl 2): s1-59.

- Araviiskaia E: Management of mild to moderate acne, slide presentation, Professor Elena Araviiskaia, MD, PhD, EADV Congress, Madrid, Oct. 11, 2019.

DERMATOLOGY PRACTICE 2020; 30(3): 28-30