It is not always the physician’s clinical experience that counts. Patient satisfaction and especially adherence depend critically on the doctor-patient conversation. Bridges can be built here.

The physician’s clinical experience is not always what counts. According to studies, patient satisfaction and adherence depend critically on the doctor-patient conversation. Communication skills are usually the key to success here. A few simple tricks can optimize the conversation.

Everyone hears only what he understands. As nonsensical as this sentence may seem at first glance, there is a lot of truth in it. If the patient cannot follow the doctor’s explanations, the risk that the therapy will not be implemented as desired is very high. Noncompliance is a widespread problem. Half of the medications are actually not taken properly – predominantly because patients have reservations about the therapy. But these are rarely addressed to the physician. Also, responsibility is often shifted to the physician. So what needs to be done to make treatment more successful? One study found that physician communication skills correlated with patient satisfaction by a factor of 0.71 [1]. A key element here is attention and appreciation, as this leads directly to an increase in patient self-esteem. In addition, the patient should participate in the decision-making process regarding therapy management in a well-informed manner. This is even more important as more and more chronic degenerative and psychosomatic diseases require the attention of the physician [2]. With them, long-term and reliable cooperation of the person concerned is essential.

First contact is crucial

The patient should therefore be the focus of interest and communication. Make decisions in a participatory and mutual agreement process [3]. However, the cornerstone of a positive conversation is already laid when the first contact is made. That’s why experts recommend picking up the patient yourself from the waiting room and shaking hands. Eye contact and listening have emerged as other important parameters. For many patients, it is important to be able to get everything off their chest in the first minute. An open start to the conversation, such as “Please tell….” opens up the conversation space in which the patient can express his or her needs without being directed in a particular direction. On average, physicians interrupt their patients after 11 to 24 seconds [4]. This can cause important information to be lost. Often, patients do not start their conversation with the most distressing symptom, but save this until the end [5]. And experience shows that patients who are not interrupted usually finish their remarks after 60 to 90 seconds anyway.

Not all problems need to be solved immediately

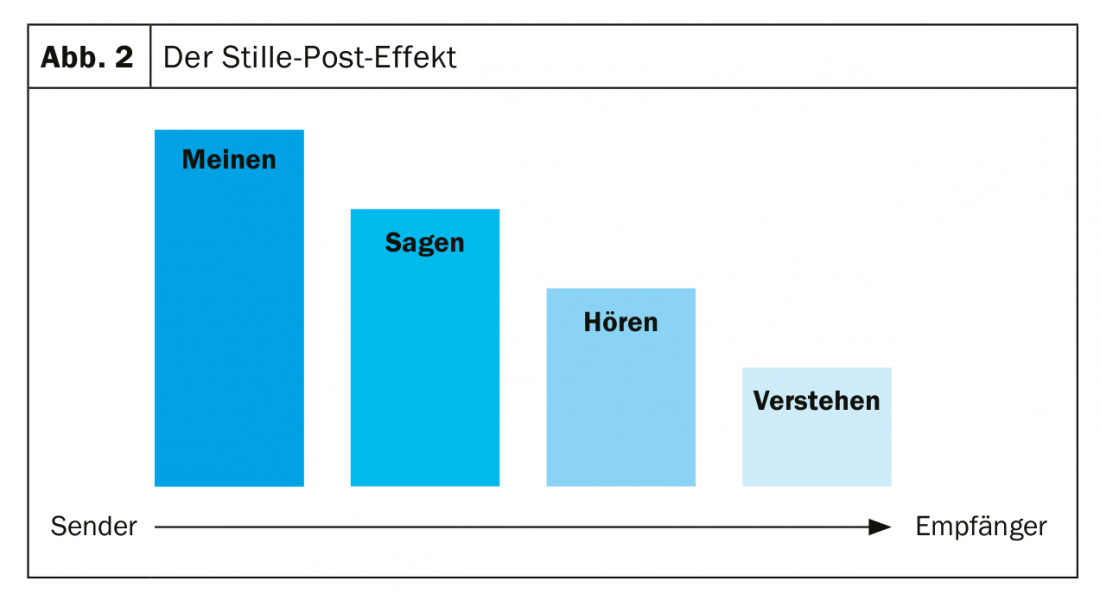

It is also important to realize that communication is not about being able to solve all problems immediately. Rather, the goal is to establish a secure and competent basis for therapy. At the same time, one should not underestimate the fact that degeneration of content occurs. There can be big differences between what the doctor means, what he says and what the patient understands. Paraphrasing and summarizing can ensure that the doctor and patient mean the same thing. In addition, pauses are important to give the affected person the opportunity to process what he or she has heard. Completion questions allow the assignment of complaints to a clinical picture. Here, too, the golden rule is to ask open rather than closed questions. The latter should be used deliberately only at the end of the case history, when the focus narrows. Then a shift is made from patient-centered to doctor-centered conversation, which clarifies the basic participatory element of the relationship.

Reduced receptivity in stressful situations

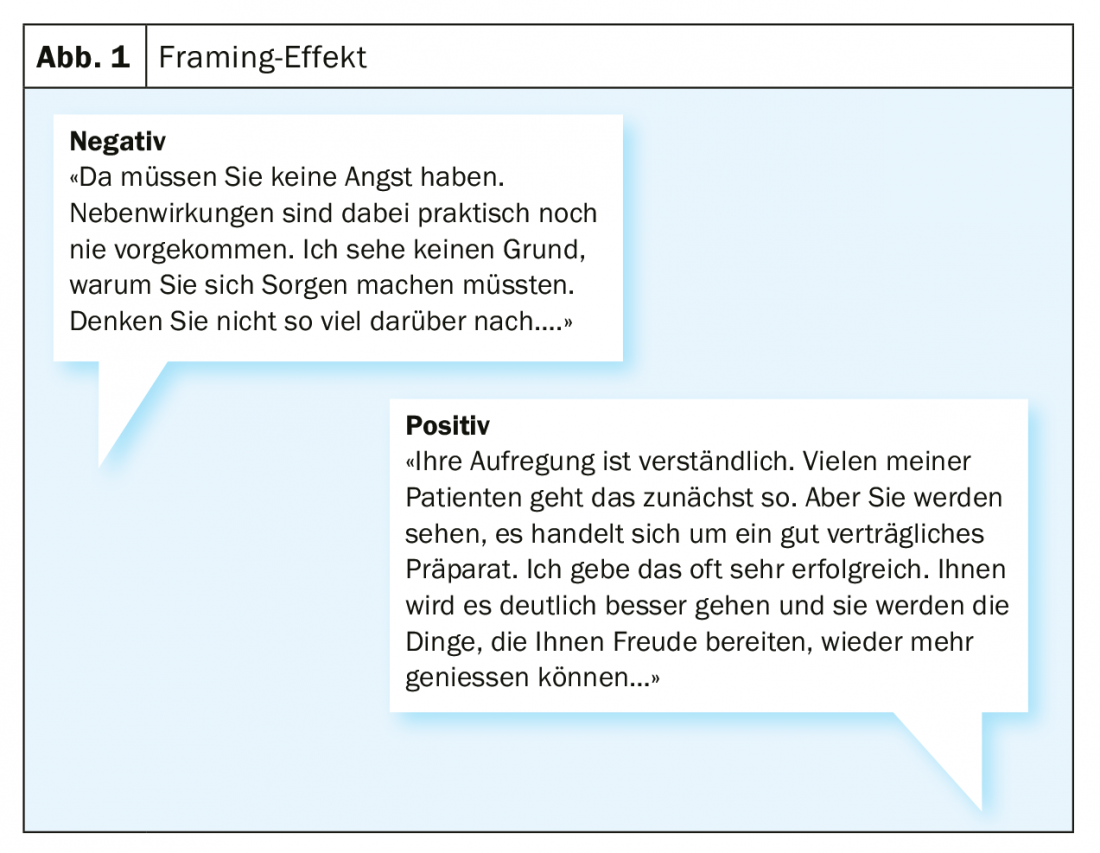

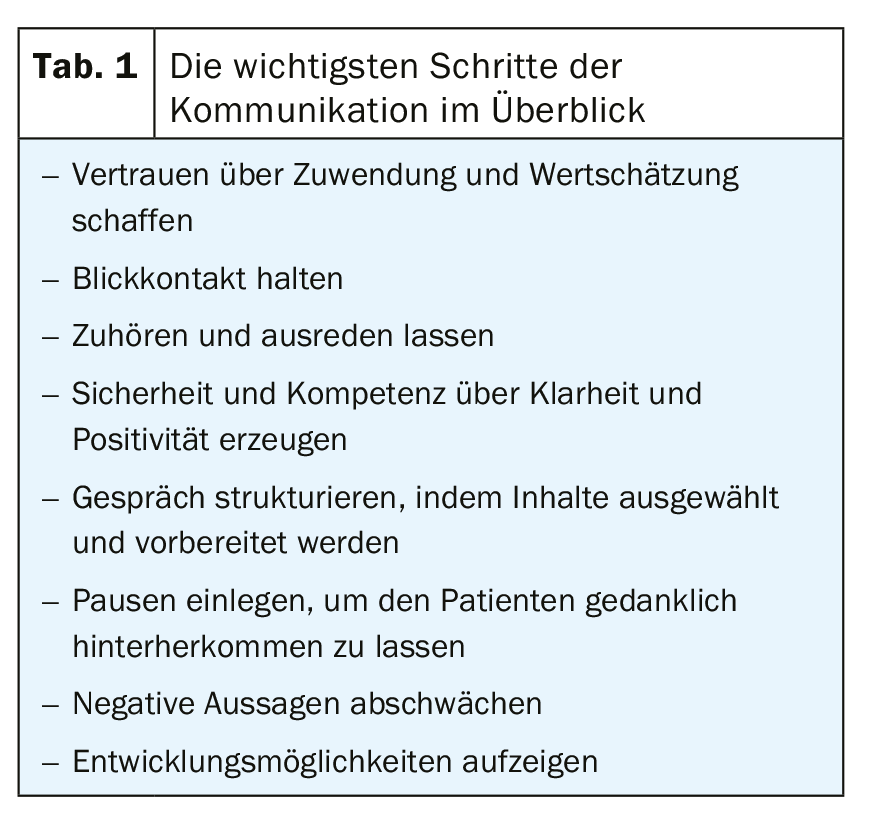

On average, people can remember seven new pieces of information. In an emotionally stressful situation, however, the absorption capacity is reduced to a minimum. This could result in the fact that 93% of all affected persons have the desire for education, but only 18% feel well educated [6]. Therefore, the information relevant to the patient should be summarized again at the end of the interview. In addition, you should always ask what is remembered from this conversation. In the process, negative exaggerations on the part of the patient should be mitigated and positive development opportunities should be pointed out (Fig.1). A nice guiding question is to consider which knowledge deficit could harm the patient until the next contact.

Avoid silent mail

It has proven successful to follow a clear structure with the description of the situation, the setting of priorities, the processing of the illness, the view of the resources up to the clarification of the treatment order in order to support the patient in the best possible way. In any doctor-patient communication, the problem of “silence post loss” can occur: There can be a big difference between what the doctor means and what he says, and one should be aware of this. What the patient hears and what he actually understands may differ significantly from the initial message (Fig. 2) . Therefore, it is not only sensible but imperative to limit oneself to a few relevant pieces of information and to be as clear as possible when conveying the message.

When suddenly everything is different

One sentence – and the patient’s world comes apart at the seams. A potentially life-threatening or life-impairing diagnosis catches most people off guard and leaves them feeling uncertain and anxious. For the patient, the entire life changes with the disease. Therefore, a careful approach adapted to the person affected is essential (table1). In this vulnerable phase, a strengthened doctor-patient relationship is all the more important. Diagnosis is often followed by an immediate onset of dependence on medical providers, not infrequently coupled with frenzied actionism. Now it is important to also pay attention to the quiet tones and to read between the lines. In particular, topics such as fear of pain, the family situation and the burden on relatives, previous experiences with the disease or later fear of recurrence are topics that need to be discussed but are not always addressed by the person affected.

One’s own sensitivities should not be underestimated

Being the bearer of bad news is also stressful for the physician. On the one hand, you should assess the situation professionally and act accordingly. On the other hand, you are also a human being with feelings and empathy, which should also be addressed. The patient is in crisis. This is defined as “an acute overload of a habitual behavioral and coping system” [7]. What follows is a state of shock, which, in addition to an intense feeling of threat, also causes a mental imbalance. Nevertheless, there is pressure to act. Not an easy situation. Flushing, sweating, palpitations, pallor and nausea may now occur as well as overexcitement, increased irritability and severe mood swings. If the patient takes his feelings out on you, it is essential to realize that this has nothing to do with you as the bearer of the news. It is not for nothing that the bearers of bad news were executed in the past. Someone who shows understanding usually gets through to the patient better than someone who shrugs off the reaction.

Even more difficult to endure than aggressive behavior, however, is speechless horror or crying. Even if the feeling of wanting to help is understandable – it is not possible. Platitudes are out of place now. You can often show your sympathy simply by handing the person a tissue. Also, offer that you are available to talk at any time if needed. Generally, such an acute stress situation lasts for several hours to a maximum of three days. If the symptoms persist for a longer period of time, the patient does not have sufficient resources to cope with the situation. The feeling of helplessness and loss of control take over. Here, coping strategies must be offered so that the crisis can be overcome.

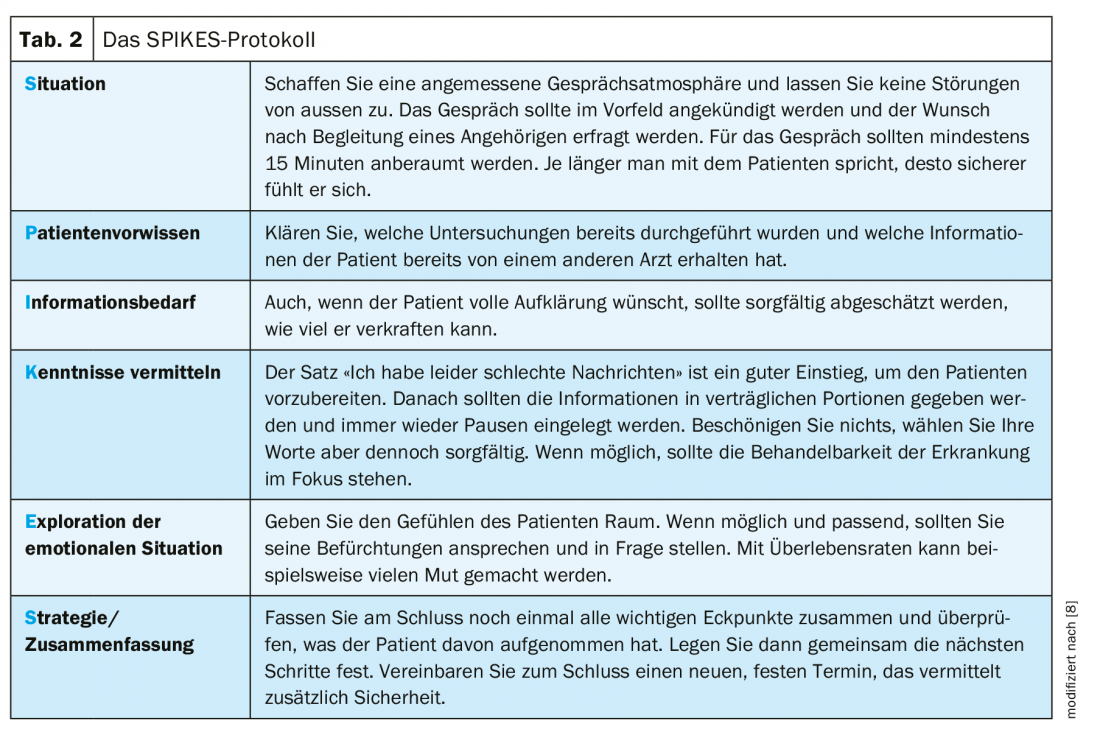

Interview guide provides assistance

One of the most popular interview guides developed specifically for oncology is the SPIKES protocol (Table 2) [8]. It aims to enable the physician to fulfill the four main goals of the bad news disclosure interview: Gathering information from the patient, communicating the medical information, supporting the patient, and eliciting the patient’s cooperation in developing a strategy or treatment plan for the future. Even with the worst news, good communication has a positive impact on receptivity, patient satisfaction, adherence, and thus a successful therapy. Friendliness, interest, and moderate physician dominance have been shown to be particularly positive [9].

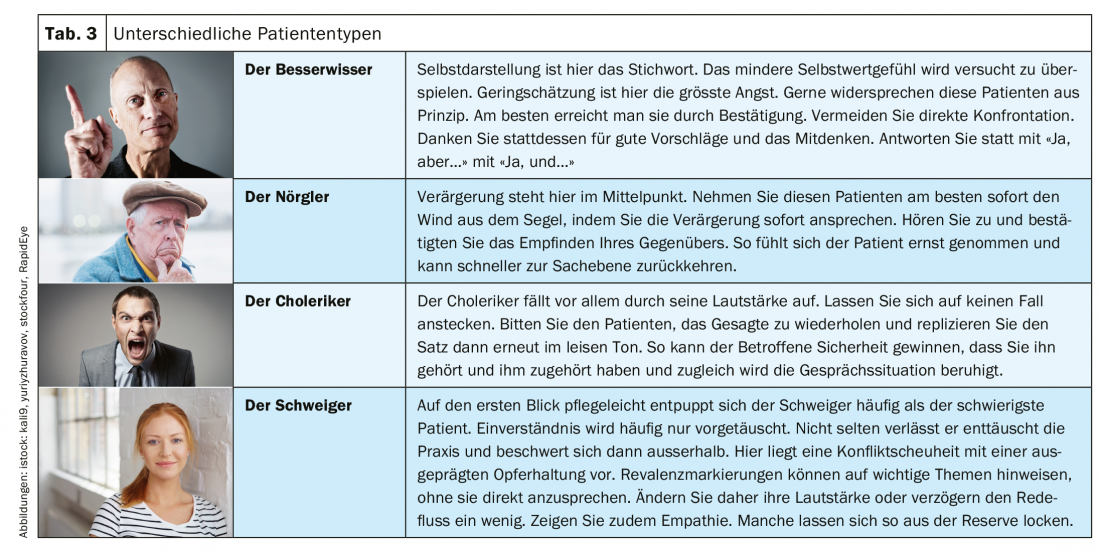

The difficult patient

The patient does not always react as the doctor expects. Then the entire operations can falter because more time, energy and attention are needed. Researchers have verified different types of patients who have developed individual strategies to be perceived as an individual and to experience emotional support (tab. 3) . Basically, the lower the self-esteem, the greater the vulnerability. Therefore, especially in this case, a prudent and skillful reaction of the physician is essential.

Also pay attention to nonverbal language

More than 90% of our communicative impact does not come from our words. Rather, it is created through body language, gestures, facial expressions, speech tempo and pitch [10]. Through practice, you can manage to appear outwardly open, calm, and approachable, while inwardly seething. However, the nonverbal signals only become convincing if we actually think in an appreciative way. A state of receptive curiosity can be helpful here. Instead of getting angry about a reaction, you can ask yourself how and on what basis it might have come about. By taking an observational stance, you don’t feel personally attacked as quickly. Ultimately, behavior depends less on the objective situation than on its interpretation. Based on one’s own experiences, hypotheses are created about how a situation will go. Therefore, two people in the same situation can also react differently.

Take-Home Messages

- Communication skills are the key to success.

- According to studies, patient satisfaction and compliance depend critically on the doctor-patient conversation.

- Communication skills usually play a greater role than the physician’s clinical experience.

- Attention and appreciation create trust.

- Pauses allow the patient to mentally get behind.

Literature:

- Langewitz W, Denz M, Keller A, et al: Spontaneous talking time at start of consultation in outpatient clinic: cohort study. BMJ 2002; 325(7366): 682-683.

- Bensing J, Langewitz W: Psychosomatic medicine: models of medical thinking and acting. Psychosomatic Medicine 2003; 415-424.

- Stewart MA, Brown JB, Weston WW, et al: Patient-centered medicine: Transforming the clinical method. Second edition. Int J Integr Care. 2005; 5: e20.

- Wilm S, Knauf A, Peters T, Bahrs O: When do primary care physicians interrupt their patients at the beginning of the consultation? Z Allg Med 2004; 80: 53-57.

- Burack RC, Carpenter RR: The predictive value of the presenting complaint. The Journal of Family Practice 1983; 16(4):749-754.

- Ochsner KN, Gross JJ, et al: Cognitive Emotion Regulation: Insights from Social Cognitive and Affective Neuroscience. Curr Dir Psychol Sci. 2008; 17(2): 153-158.

- Simmich T, Reimer C: Psychotherapeutic aspects of crisis intervention. A literature review with special reference to the last 10 years. Psychotherapist 1998, 43: 143-156.

- Baile WF, Buckman, Lenzi R, et al: SPIKES-A six-step protocol for delivering bad news: application to the patient with cancer. Oncologist 2000; 5: 302-311.

- Swedlund MP, et al: Effect of Communication Style and Physician-Family Relationships on Satisfaction With Pediatric Chronic Disease Care. Health Commun. 2012; 27: 498-505.

- Ehlich K, Rehbein J: Pattern and institution: studies in school communication. 1986.

InFo ONCOLOGY & HEMATOLOGY 2020; 8(2): 8-11.