Obesity is a risk factor for diabetes and other diseases. In addition to genetic predisposition, lifestyle factors also play a role. Weight reduction is central – is there a new patent remedy?

Worldwide, the prevalence of obesity is around 10%, and in Switzerland 1 million people are affected. “What predisposes obesity in terms of genes and environment also seems to affect diabetes,” explains Prof. Roger Lehmann, MD, University Hospital Zurich [1]. There is evidence of a positive correlation between obesity and diabetes, although age-related demographics may override this relationship. This is exemplified by Florida, a region that has a disproportionate number of older people, which is one explanation for high rates of diabetes despite low obesity prevalence. This is because the prevalence of diabetes increases with age and is highest in the over-65 age group.

Basal metabolic rate decreases with age

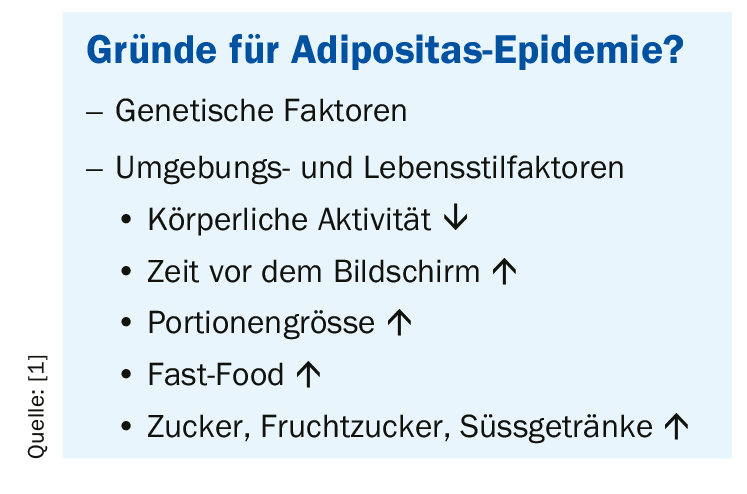

Genetic factors play an important role in the etiology of obesity. In terms of lifestyle, an unbalanced diet (increased caloric intake) and lack of exercise promote morbid obesity. Sociocultural factors and conditioning can influence lifestyle (e.g., computer age, fast food, eating habits, etc.). Certain endocrinological disorders (Cushing’s syndrome, hypothyroidism) are also a possible, though very rare, cause of obesity. However, there are also individuals with obesity who have healthy insulin and glucose metabolism and do not develop diabetes. However, morbid obesity is one of the risk factors for diabetes due to insulin resistance and b-cell decompensation, among others. Above a BMI of 25, the incidence of cardiovascular disorders and cancers increases, as well as associated and other-related mortality [2].

The fact that achieving weight reduction through the lifestyle factor of exercise alone is rather difficult is shown by the following calculation example: A 100 kg person burns about 100 kcal by walking 1 km. 1 kg of fat corresponds to 7000 kcal, extrapolated to the walking distance required for neutralization, this results in 70 km. Thus, for a weight loss of 0.5 kg per week, a walking distance of 35 km per week is required [3,4]. The basal metabolic rate can be calculated in a simplified way according to the following formula [1]: Men: 24 kcal × weight; Women: (24 kcal × weight) -10%. For the calculation of the actual energy metabolism, the power metabolism must be included, which can be expressed in the form of an activity factor (lying down = 1.2; office = 1.3-1.6; heavy work = up to 6). The formula is then as follows: Actual energy metabolic rate = basal metabolic rate × activity factor. Liver and skeletal muscle functions each account for about a quarter of basal metabolic rate, those of the brain about a fifth, and cardiac functions about a tenth [1]. With increasing age, the basal metabolic rate decreases: in 60-year-olds it is on average 10% lower than in 20-year-olds, which is related to a decrease in musculature. Accordingly, food intake should be reduced with increasing age.

Physical activity, diet, bariatric surgery, or a combination?

As shown by a study in obese elderly subjects (n=107, age range 65-75, BMI 37), the combination of both measures is much more effective in terms of weight reduction than diet or exercise alone [5]. A combination of lifestyle measures and medications is also applicable to the treatment of almost all diabetes patients and is particularly effective when antidiabetic agents of the substance classes of GLP-1 receptor agonists and SGLT-2 inhibitors are used, explains Prof. Lehmann. Up to a BMI of 30, much can be achieved with such lifestyle measures. Bariatric surgery is also a potentially highly effective measure, but it should only be considered for patients with a BMI above 35. Requirements for bariatric surgery include the following: BMI over 30, min. 2 years of dietary counseling without success (12 months is sufficient for BMI>50) and written consent for readiness for follow-up examinations over a period of five years (especially to exclude deficiency symptoms). Bariatric surgery should be performed in a multidisciplinary center (surgeons, endocrinologists, dietitians, psychiatrists).

Regarding lifestyle factor nutrition, energy density of food plays an important role. A daily calorie amount of 2100 kcal corresponds to approximately 1680 g of food. However, if foods with a high energy density are consumed, then it looks different: a fast food menu with burger, fries, apple turnover and milkshake results in an energy density of 237 kcal per 100 g. With a calorie amount of 2100 kcal/day, this corresponds to only 886 g of food extrapolated. The main nutritional problem is that although foods with a high energy density cause rapid satiety, feelings of hunger persist again after a short time. In contrast, vegetables and fruits are foods with a low energy density, which means that a larger amount corresponds to fewer calories and thus has a favorable effect on the energy balance. For example, 100 g of apples, oranges, plums or apricots are equivalent to only 41 kcal. “The Western average diet is about 160 kcal per 100 g of food,” the speaker explained.

Adherence plays a superordinate role

“It’s not the type of diet, but adherence that determines how your body weight loss is,” explains Prof. Lehmann. With maximal adherence, the greatest weight reduction is achieved regardless of diet, as shown by data from a comparative study [6]. In the DIRECT study, a longitudinal study with a large follow-up period, the effects of different diets vary over time. After one year, low-carb proved most effective, after two years the results are comparable to the Mediterranean diet, and after six years the latter is finally superior. At all time points, the low-fat diet performed the worst [7]. The so-called “PronoKal” method is a severely calorie-reduced, high-protein diet low in carbohydrates and fat, which has been shown to be very effective in terms of weight reduction (average 19.9 kg after 12 months), with this program including an increase in physical activity in addition to dietary changes [8].

Source: FOMF 2019, Zurich

Literature:

- Lehmann R: Slide presentation, Prof. Roger Lehmann, MD, Nutritional Therapy of Diabetes Mellitus. FOMF Internal Medicine – Update Refresher. 04.12.2019, Zurich.

- Calle EE, et al: Body-mass index and mortality in a prospective cohort of U.S. adults. N Engl J Med 1999; 341(15): 1097-1105.

- Weinsier RL, et al: Free-living activity energy expenditure in women successful and unsuccessful at maintaining a normal body weight. Am J Clin Nutr 2002; 75(3): 499-504.

- Schoeller DA, et al: How much physical activity is needed to minimize weight gain in previously obese women? Am J Clin Nutr 1997; 66(3): 551-556.

- Villareal DT, et al: Weight loss, exercise, or both and physical function in obese older adults. N Engl J Med 2011; 364(13): 1218-1229.

- Dansinger ML, et al: Comparison of the Atkins, Ornish, Weight Watchers, and Zone diets for weight loss and heart disease risk reduction: a randomized trial. JAMA 2005; 293(1): 43-53.

- Schwarzfuchs D, et al: Four-year follow-up after two-year dietary interventions.N Engl J Med 2012; 367: 1373-1374.

- Moreno B, et al: Comparison of a very low-calorie-ketogenic diet with a standard low-calorie diet in the treatment of obesity. Endocrine 2014; 47(3): 793-805.

HAUSARZT PRAXIS 2020; 15(1): 26-27 (published 1/27/20, ahead of print).