According to recent epidemiological data, there is evidence of increased cardiovascular risk in psoriasis and psoriatic arthritis. In order to perform adequate primary and secondary prevention of cardiovascular diseases in these patients, interdisciplinary collaboration is something very important.

Back to “Atopic dermatitis and psoriasis news”.

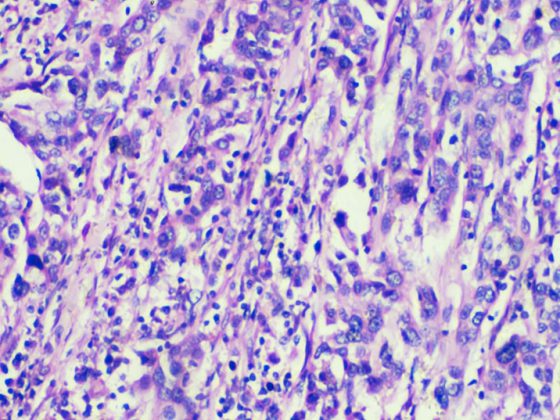

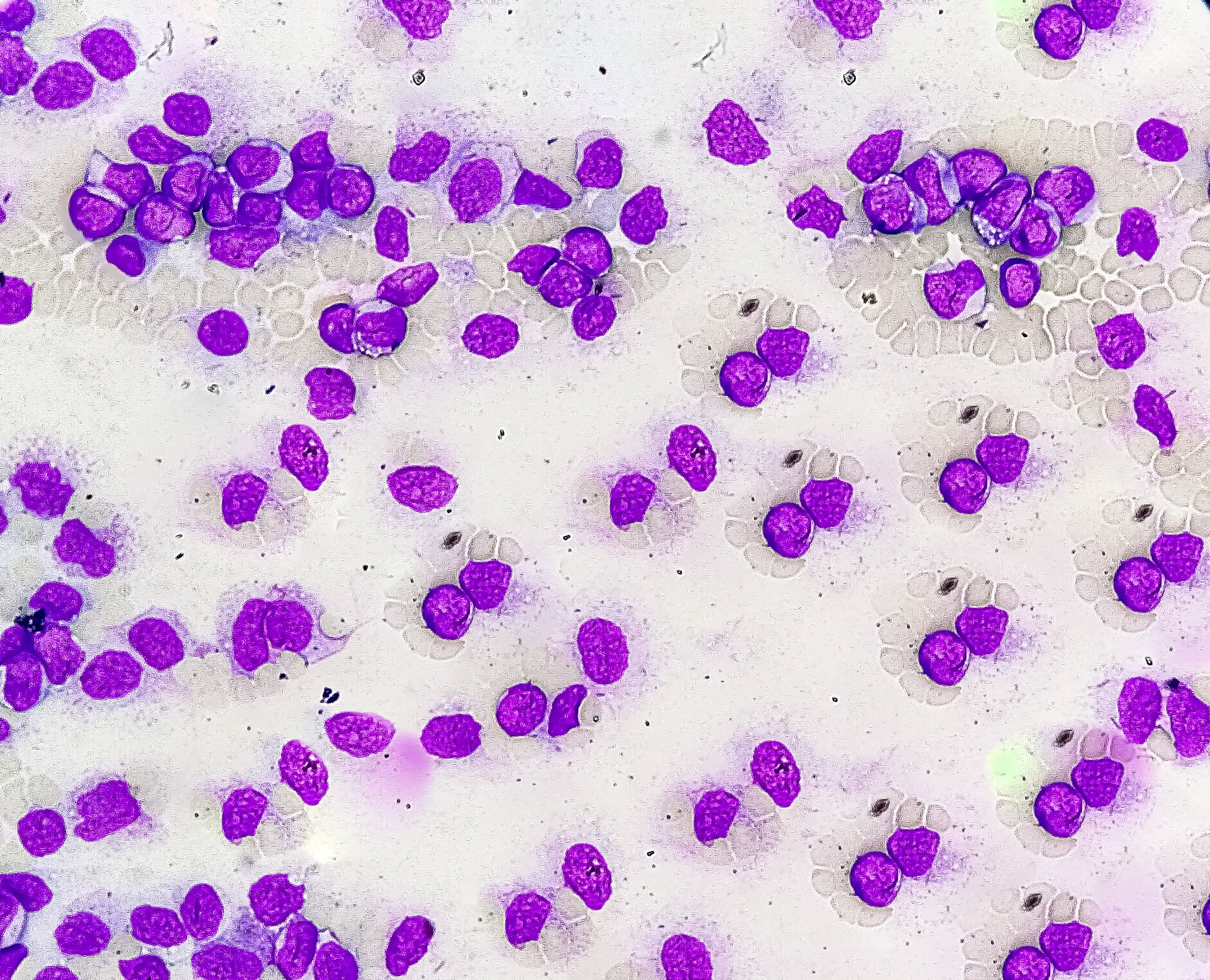

(red) Psoriasis is characterized by altered proliferation and differentiation of keratinocytes and skin inflammation, involving both the innate and adaptive immune systems and driven primarily by pathogenic T cells that produce high levels of interleukin (IL-17) in response to IL-23.

The central pathophysiological role of the IL-23/IL-17A axis in psoriasis has been confirmed by therapeutic success with targeted monoclonal antibodies. The effect of tumor necrosis factor α (TNF) antagonists is likely exerted indirectly, as TNF is an upstream inducer of IL-23 and acts synergistically with IL-17 to increase the upregulation of many psoriasis-related proinflammatory genes in keratinocytes [1].

Hypotheses on genetic and/or epigenetic factors

TNF and other inflammatory mediators can maintain a state of chronic systemic inflammation that can cause insulin resistance, endothelial dysfunction, and cardiovascular disease [2], as well as an increasing number of comorbidities, including metabolic syndrome, chronic kidney disease, gastrointestinal disease, mood disorders, and malignancies.

Thus, unlike psoriatic arthritis (PsA) and Crohn’s disease, which share genetic pathomechanisms with psoriasis, chronic inflammation would form the basis for the cardiovascular and metabolic comorbidities of psoriasis.

On the other hand, commonalities between psoriasis and some comorbidities are known in terms of genes/proteins, biological processes and signaling pathways. Thus, type 2 diabetes led the molecular comorbidity index, followed by rheumatoid arthritis, Alzheimer’s disease, myocardial infarction, and obesity [3]. Instead of genetic associations, an unfavorable lifestyle (smoking, obesity, lack of regular physical activity, and unhealthy diet) may also lead to cardiovascular comorbidity in these diseases.

Empirical evidence on comorbidity rates.

The prevalence of hypertension, obesity, hyperlipidemia, diabetes mellitus, and at least one cardiovascular event is significantly higher in PsA patients than in patients with psoriasis without arthritis, ranging from 1.54 to 2.59 with unadjusted odds ratios (ORs) [4].

Interestingly, in a cohort study in which neither very mild nor severe psoriasis was associated with an increased risk of serious cardiovascular events over a 3-5-year period, the risk of a serious cardiovascular event was 36% higher in patients with psoriasis who also had inflammatory arthritis. The prevalence of traditional cardiovascular risk factors such as obesity, hypertension, diabetes, dyslipidemia, metabolic syndrome, and smoking is increased in psoriasis [5]. The association between psoriasis and obesity and the impact of obesity on the treatment of psoriasis are well established [6]. The odds ratio (OR) for the association between psoriasis and obesity by body mass index is 1.8 (95% CI 1.4-2.2) [7]. When severity was taken into account, the overall OR for obesity was 1.46 (95% CI 1.17-1.82) for patients with mild psoriasis and 2.23 (95% CI 1.63-3.05) for patients with severe psoriasis [8]. Obesity is considered an independent risk factor for psoriasis [9]: Obesity and high abdominal fat mass double the risk of psoriasis, and long-term weight gain significantly increases the risk of psoriasis. [10].

A meta-analysis of 24 observational studies yielded a pooled OR for the association between psoriasis and hypertension of 1.58 (95% CI, 1.42-1.76). The OR for hypertension was 1.30 (95% CI 1.15-1.47) in patients with mild psoriasis and 1.49 (95% CI 1.20-1.86) in severe psoriasis [11]. In addition, the likelihood of poorly controlled hypertension appears to increase with more severe skin disease, independent of body mass index (BMI) and other risk factors [12]. In a meta-analysis of 44 observational studies, the summary OR of psoriasis associated with diabetes was 1.76 (95% CI 1.59-1.96). Patients with PsA had the highest OR (2.18, 95% CI 1.36-3.50) [13]. Patients with severe psoriasis also had a higher OR (2.10, 95% CI 1.73-2.55). In addition, diabetics with psoriasis appear to suffer from microvascular and macrovascular diabetes complications more frequently than diabetics without psoriasis [14]. In a systematic review, 20 of 25 included studies found significant associations between psoriasis and dyslipidemia with ORs ranging from 1.04 to 5.55 [15]. In studies that considered psoriasis severity, patients with severe psoriasis (range 1.36 to 5.55) were more likely to have dyslipidemia than patients with mild psoriasis (range 1.10 to 3.38) [16]. In a cross-sectional study in the United Kingdom, the prevalence of metabolic syndrome correlated directly with the body surface area (BSA) affected by psoriasis and varied in a “dose-response” fashion from mild (≤2% BSA; adjusted OR 1.22; 95% CI 1.11-1.35) to severe psoriasis (>10% BSA; adjusted OR 1.98; 95% CI 1.62-2.43) [18]. Smoking was found to be significantly associated with psoriasis, with an RR of 1.88 (95% CI, 1.66-2.13); In most publications, smoking is also associated with increased psoriasis severity [19]. Smoking is also associated with an increased risk of incident psoriasis and a possible dose-response relationship [20].

Comorbid depression as a mediator variable?

The hazard ratio for depression in psoriasis is approximately 1.4-1.5 and increases with disease severity [20,21]. Depression is a risk factor for cardiovascular disease, cardiovascular events, and mortality, and a diagnosis of depression at any time after coronary artery disease is associated with a twofold higher risk of death [21]. Therefore, the association of psoriasis with depression may be clinically relevant in terms of cardiovascular disease and mortality. In patients with psoriasis, depression is associated with an increased risk of myocardial infarction, stroke, and cardiovascular death, especially during acute depression [22]. Depression may also play an important role in promoting subclinical atherosclerosis beyond traditional cardiovascular risk factors and even psoriasis itself as a risk factor in its own right. Patients with psoriasis and self-reported depression were found to have significantly increased vascular inflammation measured by 18-fluorodeoxyglucose positron emission tomography/computed tomography (FDG PET/CT) and coronary plaque burden measured by coronary CT angiography adjusted for Framingham Risk Score, compared with patients with psoriasis alone [23].

Summary

In summary, cardiovascular burden may be higher in patients with PsA than in patients with psoriasis without arthritis. The presence of arthritis may indicate increased systemic inflammation, which can exacerbate comorbidities and cardiovascular outcomes. Obesity and associated metabolic disorders are more common in patients with psoriasis and PsA than in patients with other inflammatory arthritides. In addition, obesity is associated with an increased risk of PsA in psoriasis patients and in the general population. The high prevalence of traditional cardiovascular risk factors and metabolic disorders contributes to the high cardiovascular burden in patients with psoriasis and PsA, as well as obesity, but may also influence the risk for developing psoriasis and the impact on disease activity. The presence of systemic inflammation in combination with metabolic disorders may act synergistically to increase cardiovascular risk in these patients.

CONCLUSION: There is a strong need for improvement in primary and secondary prevention of cardiovascular disease in patients with psoriasis and psoriatic arthritis. The components of metabolic syndrome should be appropriately diagnosed. Lifestyle changes should be actively encouraged. Risk stratification should be adjusted in patients with psoriasis and PsA, and appropriate pharmaceutical interventions should be implemented with adequate monitoring of their efficacy. Colleagues caring for patients with psoriasis and/or PsA, in collaboration with general practitioners and cardiologists, should play an active role in achieving these goals.

Back to “Atopic dermatitis and psoriasis news”.

Literature:

- Hawkes JE, Chan TC, Krueger JG: Psoriasis pathogenesis and the development of novel targeted immune therapies. J Allergy Clin Immunol 2017; 140:645-653. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2017.07.004.

- Boehncke WH, Boehncke S, Tobin AM, Kirby B: The ‘psoriatic march’: A concept of how severe psoriasis may drive cardiovascular comorbidity. Exp Dermatol 2011; 20: 303-307. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0625.2011.01261.x.

- Sundarrajan S, Arumugam M: Comorbidities of psoriasis-Exploring the links by network approach. PLoS ONE. 2016;11:e0149175. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0149175.

- Husted JA, et al: Cardiovascular and other comorbidities in patients with psoriatic arthritis: A comparison with patients with psoriasis. Arthritis Care Res. (Hoboken) 2011; 63: 1729-1735. doi: 10.1002/acr.20627.

- Puig L, Kirby B, Mallbris L, Strohal R: Psoriasis beyond the skin: A review of the literature on cardiometabolic and psychological co-morbidities of psoriasis. Eur J Dermatol 2014; 24: 305-311.

- Jensen P, Skov L: Psoriasis and obesity. Dermatology 2016; 232: 633-639. doi: 10.1159/000455840.

- Miller IM, Ellervik C, Yazdanyar S, Jemec GB: Meta-analysis of psoriasis, cardiovascular disease, and associated risk factors. J Am Acad Dermatol 2013; 69: 1014-1024. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2013.06.053.

- Armstrong AW, Harskamp CT, Armstrong EJ: The association between psoriasis and obesity: A systematic review and meta-analysis of observational studies. Nutr Diabetes 2012; 2:e54. doi: 10.1038/nutd.2012.26.

- Setty AR, Curhan G, Choi HK: Obesity, waist circumference, weight change, and the risk of psoriasis in women: Nurses’ Health Study II. Arch Intern Med 2007; 167: 1670-1675. doi: 10.1001/archinte.167.15.1670.

- Snekvik I, et al: Obesity, waist circumference, weight change, and risk of incident psoriasis: Prospective data from the HUNT study. J Investig Dermatol 2017; 137: 2484-2490. doi: 10.1016/j.jid.2017.07.822.

- Armstrong AW, Harskamp CT, Armstrong EJ: The association between psoriasis and hypertension: A systematic review and meta-analysis of observational studies. J Hypertens 2013; 31: 433-442. doi: 10.1097/HJH.0b013e32835bcce1.

- Takeshita J, et al: Effect of psoriasis severity on hypertension control: A population-based study in the United Kingdom. JAMA Dermatol 2015; 151: 161-169. doi: 10.1001/jamadermatol.2014.2094.

- Coto-Segura P, et al: Psoriasis, psoriatic arthritis and type 2 diabetes mellitus: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Br J Dermatol 2013; 169: 783-793. doi: 10.1111/bjd.12473.

- Armstrong AW, et al: Psoriasis and risk of diabetes-associated microvascular and macrovascular complications. J Am Acad Dermatol 2015; 72: 968-977. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2015.02.1095.

- Ma C, Harskamp CT, Armstrong EJ, Armstrong AW: The association between psoriasis and dyslipidaemia: A systematic review. Br J Dermatol 2013; 168: 486-495. doi: 10.1111/bjd.12101.

- Singh S, Young P, Armstrong AW: An update on psoriasis and metabolic syndrome: A meta-analysis of observational studies. PLoS ONE 2017; 12:e0181039. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0181039.

- Langan SM, et al. Prevalence of metabolic syndrome in patients with psoriasis: A population-based study in the United Kingdom. J Investig Dermatol 2012; 132: 556-562. doi: 10.1038/jid.2011.365.

- Richer V, et al: Psoriasis and smoking: A systematic literature review and meta-analysis with qualitative analysis of effect of smoking on psoriasis severity. J Cutan Med Surg 2016; 20: 221-227. doi: 10.1177/1203475415616073.

- Schmitt J, Ford DE: Psoriasis is independently associated with psychiatric morbidity and adverse cardiovascular risk factors, but not with cardiovascular events in a population-based sample. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol 2010; 24 :885-892. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-3083.2009.03537.x.

- Kurd SK, Troxel AB, Crits-Christoph P, Gelfand JM: The risk of depression, anxiety, and suicidality in patients with psoriasis: A population-based cohort study. Arch Dermatol 2010; 146: 891-895.

- May HT, et al: The association of depression at any time to the risk of death following coronary artery disease diagnosis. Eur Heart J Qual Care Clin Outcomes 2017; 3: 296-302. doi: 10.1093/ehjqcco/qcx017.

- Egeberg A, et al: Impact of depression on risk of myocardial infarction, stroke and cardiovascular death in patients with psoriasis: A danish nationwide study. Acta Derm Venereol 2016; 96: 218-221. doi: 10.2340/00015555-2218.

- Aberra TM, et al. Self-reported depression in psoriasis is associated with subclinical vascular diseases. Atherosclerosis 2016; 251: 219-225. doi: 10.1016/j.atherosclerosis.2016.05.043.

- Armstrong AW, Harskamp CT, Dhillon JS, Armstrong EJ: Psoriasis and smoking: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Br J Dermatol 2014; 170: 304-314. doi: 10.1111/bjd.12670.

DERMATOLOGIE PRAXIS 2019; 29(3): 28-29