Insomnia is a common health problem and is associated with high levels of distress. Early, effective treatment is important – also preventively. There are several effective non-pharmacological treatment options that can be used in a target-specific manner.

Most people are familiar with problems falling asleep or sleeping through the night, which are often triggered by acute stressful situations and usually pass again after a short time without specific intervention. However, if the sleep disturbances persist for at least one month and are associated with a significant impairment of daytime well-being such as concentration disorders or severe fatigue, the condition is referred to as insomnia [1]. Regular sleep disturbances affect about 30% of the population [2], with about 6% meeting criteria for insomnia [3]. Specific treatment should be given here, otherwise the risk of chronicity is high. Chronic sleep disorders are associated with a reduced quality of life for those affected and cause costs in terms of absenteeism and reduced performance at work.

Current developments in diagnostics

In older editions of the most important diagnostic systems, the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM-IV) and the International Classification of Diseases (ICD-10) [4,5], a differentiation was made between primary and secondary insomnia. While primary insomnia occurs in isolation, that is, without a directly identifiable cause, secondary insomnia is evaluated as a consequence of another condition. Here, the insomnia occurs, for example, due to anxiety or brooding in the case of mental illnesses or due to pain in the case of physical illnesses. At first glance, this differentiation seems to make sense, but in practice it has proven to be problematic and untenable.

Rather, there is often a bidirectional relationship between sleep disorders and other diseases: Many mental and physical illnesses are accompanied by sleep disorders, e.g. due to increased anxiety or pain at night. Conversely, sleep disorders can also initially occur in isolation and then increase the risk of developing depression, another mental illness, or cardiovascular disorders [6,7].

Differentiation into primary and secondary insomnia resulted in practice in targeting only primary sleep disorders. In secondary insomnia, on the other hand, it was assumed that treatment of the underlying disease would be sufficient and that the sleep disorders would remit on their own with remission of the same. However, it is now believed that insomnia should be treated in a disorder-specific manner even in the presence of a comorbid condition and that this often has a positive effect on comorbid conditions [8]. Based on these findings, a diagnostic reclassification has taken place in the current edition of the American DSM (DSM-5): An “insomnia disorder” can be diagnosed independently of the presence of other illnesses. The division into primary and secondary insomnia is no longer applicable. This reinforces the importance of sleep for mental and physical health and indicates that if relevant sleep disorders are present, disorder-specific treatment for insomnia should be provided in all cases. The ICD, which is the guideline for diagnosis in Europe, will soon be published in a new, eleventh edition, in which a similar reorganization regarding insomnia diagnostics is expected.

Current development regarding pathophysiology

For the diagnosis and treatment of insomnia, a sleep laboratory examination is usually not necessary. Diagnostic criteria such as sleep onset and sleep maintenance disorders are inquired about; a subjectively perceived disturbance of sleep is sufficient for the diagnosis. However, when affected individuals are examined by polysomnography in a sleep laboratory, the results are often surprising: while patients report sleeping only a few hours or almost not at all, the sleep laboratory findings are often only slightly abnormal. A review of several sleep laboratory studies found that patients with insomnia sleep an average of only 25 minutes shorter than subjects without sleep disturbance and take an average of only seven minutes longer to fall asleep [9]. These findings are in contrast to the subjective experience of the patients with a reduced sleep time, sometimes by hours. A common explanation for this is that patients with insomnia misperceive their sleep (“misperception”), whereas polysomnography accurately measures the sleep-wake state. Reasons for misperception could be memory bias due to increased introspection and fear of insomnia [10]. However, even when patients are awakened directly from polysomnographically detected sleep and asked whether they have just been asleep, they more often than subjects without sleep disturbance show a misperception, i.e., answer “I was awake” [11]. This cannot be readily explained by memory bias and overestimation of waking times on the following day.

An alternative recent explanation is that polysomnography is not sensitive enough to image subtle changes in sleep in patients with insomnia. In other words, it could also be that patients with insomnia perceive their condition correctly and polysomnography is an inadequate measurement.

Polysomnographic sleep examinations are performed in the standard examination with only a few electrodes on the surface of the skull. This was previously thought to map sleep with sufficient accuracy, as sleep was understood to be a global state of the entire brain. However, recent research shows that this is not the case. Local sleep phenomena have been known for a long time in animals. Dolphins and other animals, for example, can sleep with only one hemisphere of the brain while the other hemisphere remains awake, scanning the environment for threats and maintaining a baseline activity. Studies in rats have also shown that on the one hand there are local waking phenomena in parts of the brain during sleep, and on the other hand there are local sleep phenomena during wakefulness. For example, in rats showing typical waking behavior, i.e., being responsive and moving normally, slow brain waves characteristic of sleep could be recorded locally (at some electrodes) in intracerebral leads. We can therefore speak of parts of the brain being “asleep” while the rat is in a waking state. At the behavioral level, this phenomenon is associated with errors in tasks that require the corresponding brain area [12]. During the experiments, electrodes were implanted in the brains of the rats in order to be able to derive deeper brain regions. This is not performed in humans for ethical reasons for experimental purposes. However, such a procedure may be necessary in patients with severe, refractory epilepsy to identify a seizure focus in preparation for therapeutic surgery. In the course of such studies, it has also been shown in patients that there are local “islands of wakefulness” during sleep, namely fast brain waves typical of the waking state [13]. These have been found, for example, in the motor cortex, which is important for controlling movement. Another way to further investigate these phenomena in humans without invasive intervention in the brain is the so-called “high density EEG”.

Here, a large number of electrodes (e.g. 128) are placed on the head with the aim of imaging differential brain activity at different locations in the brain. Studies that used this method were able to confirm that sleep in humans is by no means as global as previously thought [14]. Sleep-typical slow brain waves tend to occur locally and are repeatedly interrupted by local faster, wake-typical brain activity.

In summary, this means that newer, more sensitive measurement methods can record subtleties of sleep that are not visible in the routine polysomnography normally used. This may help to further unravel the mystery of sleep (mis)perception in patients with insomnia. An initial pilot study in this area has shown that patients with insomnia do indeed experience increased wake-like brain activity during sleep [14]. The affected brain areas were located in the sensory cortex, that is, in an area that is important for the perception of one’s own body. If this area suddenly “wakes up” during sleep, this could explain why patients subjectively feel awake or awake-like, although most of the brain is asleep. To date, local sleep and local wakefulness have not been studied directly in the context of sleep perception. Further studies will investigate whether these two phenomena are related, or whether local wakefulness during sleep can explain the altered sleep perception in patients with insomnia.

Now that current developments in the diagnosis and pathogenesis of sleep disorders have been presented, therapeutic options will be discussed below.

Cognitive behavioral therapy of insomnia (KVT-I)

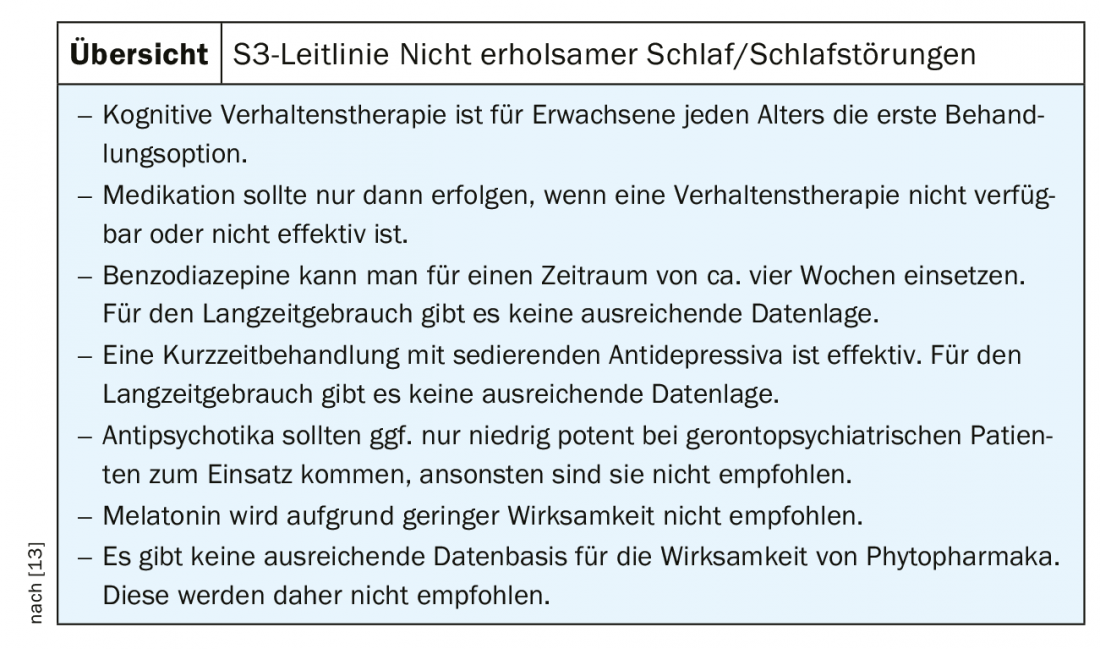

It has been known for decades from extensive research that Cognitive Behavioral Therapy for Insomnia (CBT-I) has large, long-lasting therapeutic effects in approximately three-quarters of patients and is therefore superior to pharmacotherapy. However, this finding has only recently found its way into international guidelines. Following the current European guideline on the diagnosis and treatment of insomnia, recently developed under the coordination of Prof. Riemann, Freiburg, Germany, KVT-I is the treatment of first choice in patients with and without comorbidity [15]. The American College of Physicians practice guideline and the American Acadamy of Sleep Medicine practice recommendations reach the same conclusion [16,17]. Only if KVT-I cannot be performed or is unsuccessful should drug treatment be considered. In this case, a benzodiazepine may be administered for a short period of time, or treatment may be with low-dose sedating antidepressants [15]. The recommendations of the German Guideline are consistent with the elaborated recommendations and are summarized in Table 1 [18].

KVT-I is divided into different components: education, relaxation, behavior modification and cognitive therapy (overview).

With KVT-I, a majority of those treated can achieve significant improvement in insomnia [19]. However, a susceptibility to sleep disturbances often persists. Because of better long-term effects, which usually remain stable for at least two years after the end of therapy, KVT-I is preferable to drug treatment.

If such behavioral therapy is not feasible or does not lead to success, drug treatment may be considered. However, treatment with benzodiazepines or benzodiazepine receptor agonists (Z-substances) is advisable only for a limited period (about four weeks), otherwise there is a risk of tolerance and dependence developing. This means that the medication gradually loses its effect despite a constant dosage, which causes some patients to increase the dose and become dependent. Instead, low-dose antidepressants can be used over a longer period of time (e.g., trimipramine, doxepin, or trazodone). As a rule, no loss of effect occurs here. However, there is little research on long-term treatments of sleep disorders with these substances.

As described, KVT-I is the best treatment option for people with insomnia. However, a problem within the care system is that many people do not receive this treatment despite the recommendation of international guidelines. The main reason is probably that this is rarely offered. Primary care physicians often do not know enough about KVT-I or have no way to refer to a specialist because few psychotherapists and physicians specialize in sleep. Sleep has so far played a subordinate role in the training of psychotherapists and also specialists in various fields, which is why even specialists often do not use KVT-I, which is actually not too complex. Accordingly, medications are still frequently prescribed in an initial treatment attempt, often including benzodiazepines or benzodiazepine receptor agonists, although this clearly contradicts treatment guidelines.

Internet based therapy

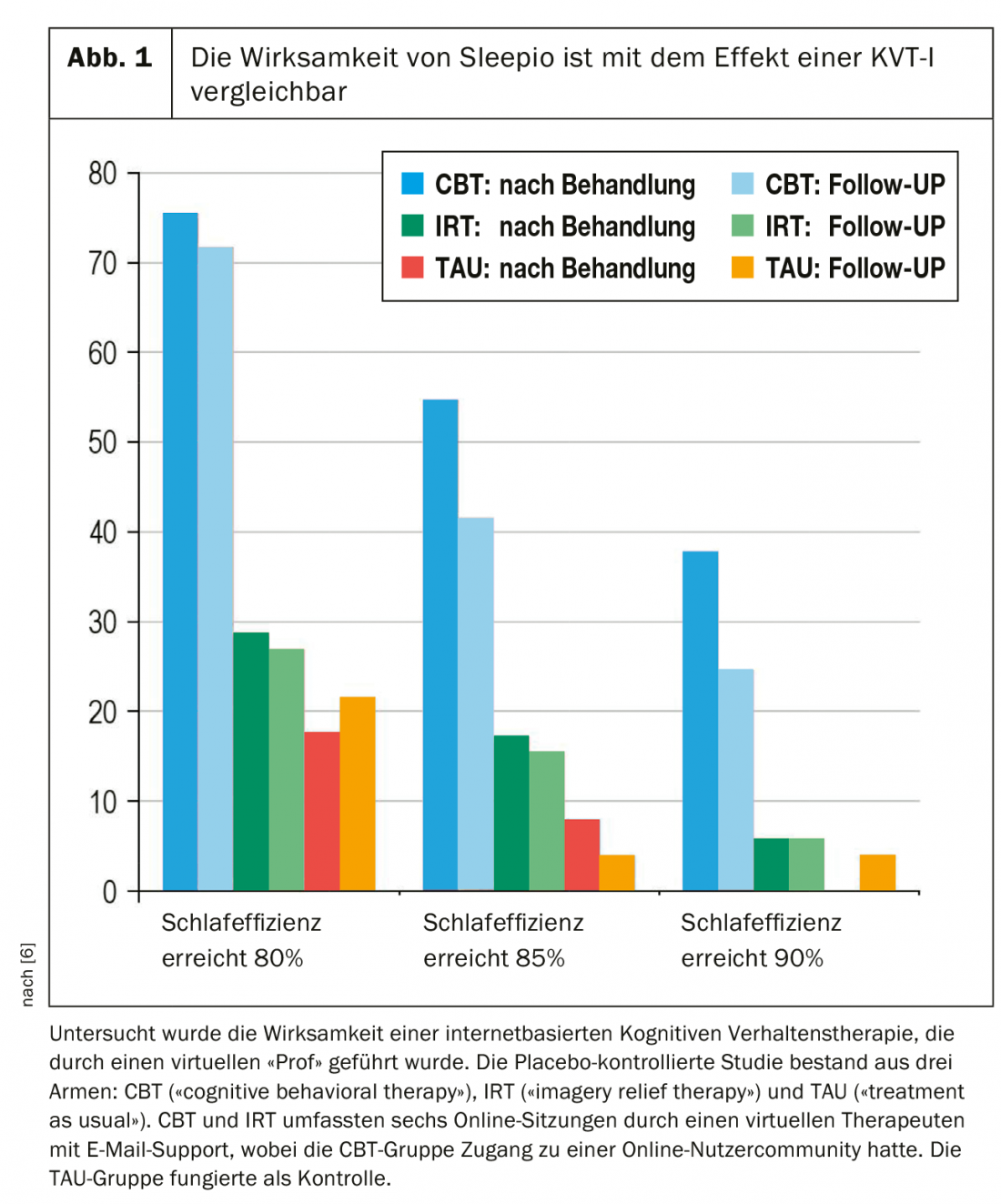

Internet-based treatment programs are one way to improve and expand treatment services for patients with insomnia. Here, the treatment modules are implemented in a computer program or smartphone app. Patients can access advice and information about sleep via descriptive graphics or videos. Data on one’s own sleep behavior can be entered into the application, which then helps to calculate a personal optimal sleep window. Patients can also be supported in the use of relaxation exercises via recorded instructions. The Sleepio program, for example, developed by Scottish sleep researcher Colin Espie, has become well-known. Here, the user is guided through the program by a virtual therapist, the “Prof”, and supported in case of questions. Users can also share their experiences in a forum. Sleepio has been extensively studied scientifically and has been shown in clinical trials to have effects similar to those of KVT-I performed in person by a therapist (Fig. 1) [20]. A similar program is SHUTi (pronounced “shut eye”), developed and studied in the United States, which has also been shown to be effective in treating insomnia. Preliminary data may suggest that the program may even help prevent the development of depression. However, there are no robust data on this to date and further research is pending [21]. Online therapy programs have been studied primarily in patients with insomnia without serious comorbidity. It is conceivable that patients with severe mental illnesses are overwhelmed by the complexity of such a program and also find it difficult to muster the motivation to carry it out independently and regularly. Further work is needed here.

One advantage of Internet-based therapy is that patients can use it flexibly, regardless of time and place, thus avoiding travel. This can be a great advantage, especially in rural areas where there are no trained therapists locally who can teach KVT-I. One drawback is that face-to-face contact with the therapist often increases treatment motivation and patient engagement. A good relationship with the therapist can help work through setbacks in therapy and stay in treatment despite difficulties that arise. Accordingly, dropout rates are often high for online-only therapies.

Depending on the program, the applications can also be combined with direct therapist contact. CBT4CBT (“Computer-Based Training for Cognitive Behavioral Therapy”) is the name of an application that specializes in patients with addiction disorders. The computer-based application is intended for patients who are already undergoing treatment. The CBT4CBT app is prescribed by the treating therapist and is used to reinforce and further practice specific content of the therapy between therapy sessions and after the end of treatment, such as skills that help resist the pressure of addiction. The scientific evaluation showed that the program is well evaluated by the patients and that with the help of the app the therapy success can be improved compared to a conventional treatment [22].

Developing a comparable application for patients with insomnia is the goal of a study currently being developed at the University Psychiatric Services Bern. A smartphone app is to be developed that will be used initially during treatment on the ward and later at home to improve the patient’s own sleep behavior. A novel aspect is that, unlike Sleepio or SHUTi, for example, the program is specifically tailored to patients with severe mental illness and is intended to be prescribed and used in the context of existing psychiatric treatment. Specialist therapists can initially assist with the application before patients start using it independently at home.

Acceptance and Committment Therapy (ACT) for Insomnia

Another area of concern relates to patients who receive KVT-I but do not benefit from it. At approximately 75%, the rate of patients who are able to achieve satisfactory improvement of their symptoms is quite high. However, even when using KVT-I, therapists repeatedly experience patients who do not benefit well from this treatment. One reason is often that sleep restriction is not properly applied for fear of feeling too bad the next day. Patients dare not significantly reduce their bedtime, continue to lie in bed for long periods of time, or sleep during the day, so they do not build up enough sleep pressure and the intervention cannot work. Another common problem is that although sleep improves, daytime well-being remains poor, e.g., due to pronounced fatigue, exhaustion, or anxiety.

Acceptance and Commitment Therapy (ACT) is a treatment modality that can be used when KVT-I has been used but has not helped sufficiently. Here, mindfulness exercises and other strategies are used that can help to better deal with unpleasant feelings. This can reduce anxiety related to sleep restriction and related to other situations. Another important therapy component of ACT is working with values: Together with the patients, we work out what is important to them in life and which activities they experience as fulfilling and meaningful. Patients are then helped to live their lives in accordance with these values and goals. This can also significantly improve daytime well-being independently of sleep, e.g. when patients become more active overall and turn to activities that are important to them. In addition, work with personal values can be used to target the time that is “freed up” by the sleep restriction (e.g., when bedtime is reduced from the original nine hours to six hours). Reviews have shown ACT to be helpful for various disorders, such as chronic pain and depression. For patients with insomnia, there is so far only one small pilot study from our research group, which gave first indications of good efficacy in terms of improved quality of life [23]. We are currently planning to further investigate ACT now in a clinical trial with an active comparison group.

Non-invasive brain stimulation

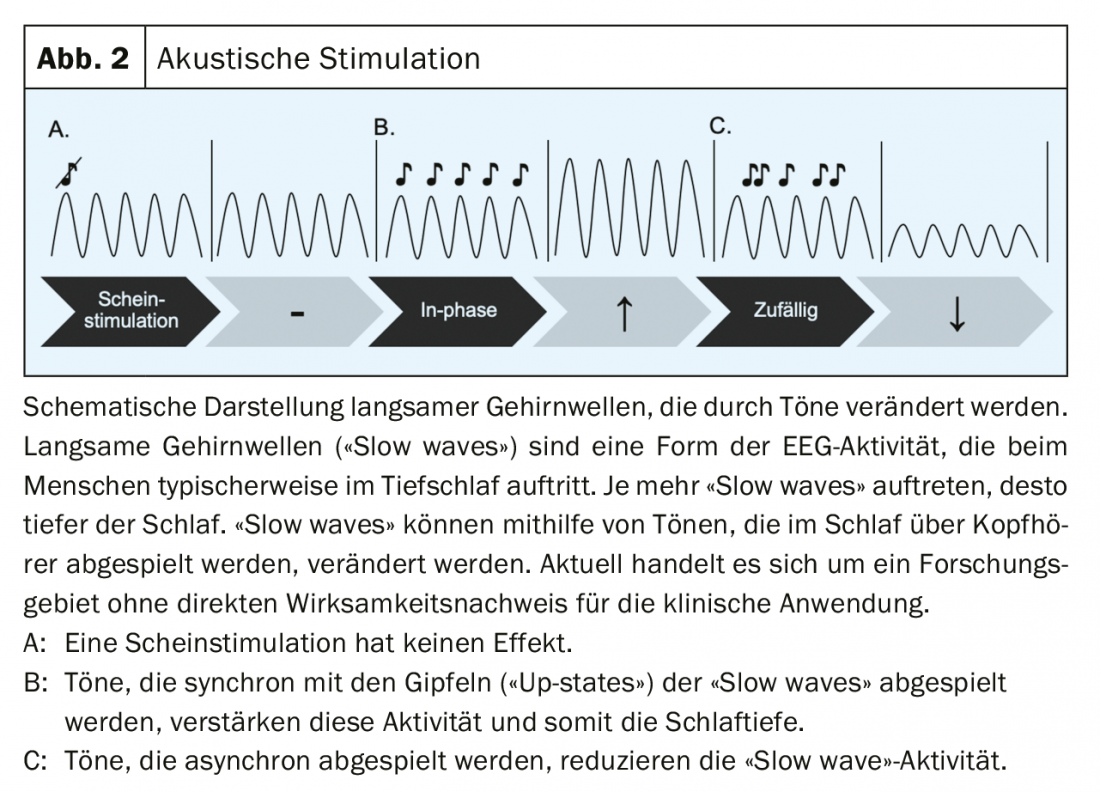

Sleep is controlled in the brain via two different pathways in particular. Once via the ascending reticular activating system (ARAS), which originates from the brainstem and activates the thalamus and ultimately neurons of the cortex via ascending pathways. On the other hand, there is also a so-called “top down” system that originates from the cortex and projects from there in a feedback loop to the thalamus [24]. The first pathway is traditionally achieved through sleep-inducing medications. The second “top down” pathway can possibly be influenced by noninvasive brain stimulation acting through the scalp (e.g., with electrical stimulation) or via the sensory organs (e.g., with auditory stimulation) on the cortex. Slow, sleep-typical brain activity can be enhanced with the help of acoustic stimulation, for example [25]. In this process, certain tones are played to the sleeping person via headphones – whenever a slow brain wave is seen in the EEG. This increases the “slow wave” activity (Fig. 2). This could be used to reduce the spontaneous awakening of individual brain regions and thus make sleep more restful. Further work is needed to test these ideas further.

Summary and outlook

Recent guidelines on insomnia highlight that it is a common health problem, is associated with high levels of distress for sufferers, and can contribute to the emergence of mental and physical illness. From this, it can be inferred that early, effective treatment of insomnia can contribute to improved health in general and may also be used for prevention. Future research in sleep and mental health should therefore focus on improving sleep specifically, with the goal of improving health in general. An important step is to better integrate guideline-based treatment, KVT-I, into the existing health care system, for example, by developing smartphone-based applications – including for people with mental illness. Another important aspect is the development of new, non-drug therapies for sufferers who do not benefit from standard treatment. Here, methods of non-invasive brain stimulation, especially auditory stimulation, could be used in addition to acceptance and commitment therapy.

Take-Home Messages

- Insomnia represents a common health problem with a high level of suffering. It is often associated with psychological comorbidities.

- According to DSM-5, insomnia can now be diagnosed regardless of the presence of other disorders.

- Early, effective treatment is important – also preventively.

- Future research should therefore focus on improving sleep specifically with the goal of improving health in general.

- The therapy of choice is Cognitive Behavioral Therapy for Insomnia (KVT-I). It needs to be better built into the existing healthcare system, such as through the development of smartphone-based applications. Other approaches include acceptance and commitment therapy and methods of noninvasive brain stimulation, particularly auditory stimulation.

Literature:

- American Psychiatric Association: Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders. Fifth Edition. DSM-5. 2013.

- Stringhini S, et al: Association of socioeconomic status with sleep disturbances in the Swiss population-based CoLaus study. Sleep Med 2015; 16(4): 469-476.

- Schlack R, et al: [Frequency and distribution of sleep problems and insomnia in the adult population in Germany: results of the German Health Interview and Examination Survey for Adults (DEGS1)]. Bundesgesundheitsblatt Health Research Health Protection 2015; 56: 740-748.

- American Psychiatric Association: Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders. Fourth Edition, Text Revision. 2000.

- WHO: ICD-10. International statistical classification of diseases and related health problems: tenth revision, 2nd ed. 2003.

- Hertenstein E, et al: Insomnia as a predictor of mental disorders: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Sleep Med Rev 2019; 43: 96-105.

- Sofi F, et al: Insomnia and risk of cardiovascular disease: a meta-analysis. Eur J Prev Cardiol 2014; 21(1): 57-64.

- Blom K, et al: Three-Year Follow-Up Comparing Cognitive Behavioral Therapy for Depression to Cognitive Behavioral Therapy for Insomnia, for Patients With Both Diagnoses. 2017; 40(8): doi: 10.1093/sleep/zsx108.

- Baglioni C, et al: Sleep changes in the disorder of insomnia: a meta-analysis of polysomnographic studies. Sleep Med Rev 2014; 18(3): 195-213.

- Harvey AG, Tang NKY: (Mis)perception of sleep in insomnia: a puzzle and a resolution. Psychol Bull 2012; 138(1): 77-101.

- Feige B, et al.: Insomnia-perchance a dream? Results from a NREM/REM sleep awakening study in good sleepers and patients with insomnia. Sleep 2018; 41(5): doi: 10.1093/sleep/zsy032

- Vyazovskiy VV, et al: Local sleep in awake rats. Nature 2011; 472(7344): 443-447.

- Nobili L, et al: Local aspects of sleep: observations from intracerebral recordings in humans. Prog Brain Res 2012; 199: 219-232.

- Riedner BA, et al: Regional Patterns of Elevated Alpha and High-Frequency Electroencephalographic Activity during Nonrapid Eye Movement Sleep in Chronic Insomnia: A Pilot Study. Sleep 2016; 39(4): 801-812.

- Riemann D, et al: European guideline for the diagnosis and treatment of insomnia. J Sleep Res 2017; 26(6): 675-700.

- Morgenthaler T, et al: Practice parameters for the psychological and behavioral treatment of insomnia: an update. An american academy of sleep medicine report. Sleep 2006; 29(11): 1415-1419.

- Qaseem A, et al: Management of Chronic Insomnia Disorder in Adults: A Clinical Practice Guideline From the American College of Physicians. Ann Intern Med 2016; 165(2): 125-133.

- Riemann D, et al: S3 guideline non-restorative sleep/sleep disorders. Somnology 2017; 21: 2-44.

- Harvey AG, Tang NKY: Cognitive behaviour therapy for primary insomnia: can we rest yet? Sleep Med Rev 2003; 7(3): 237-262.

- Espie CA, et al: A randomized, placebo-controlled trial of online cognitive behavioral therapy for chronic insomnia disorder delivered via an automated media-rich web application. Sleep 2012; 35(6): 769-781.

- Christensen H, et al: Effectiveness of an online insomnia program (SHUTi) for prevention of depressive episodes (the GoodNight Study): a randomised controlled trial. Lancet Psychiatry 2016; 3(4): 333-341.

- Carroll KM, et al: Computer-assisted delivery of cognitive-behavioral therapy for addiction: a randomized trial of CBT4CBT. Am J Psychiatry 2008; 165(7): 881-888.

- Hertenstein E, et al: Quality of life improvements after acceptance and commitment therapy in nonresponders to cognitive behavioral therapy for primary insomnia. Psychother Psychosom 2014; 83(6): 371-373.

- Krone L, et al: Top-down control of arousal and sleep: Fundamentals and clinical implications. Sleep Med Rev 2017; 31: 17-24.

- Ngo HV, et al: Induction of slow oscillations by rhythmic acoustic stimulation. J Sleep Res 2013; 22(1): 22-31.

InFo NEUROLOGY & PSYCHIATRY 2019; 17(4): 6-12.