Sexually transmitted infections of the anorectum can mimic inflammatory bowel disease. For the correct diagnosis, the anamnesis interview should take place in a trusting and empathic atmosphere.

A brief case description: a 41-year-old man self-referred for mucous-bloody discharge per anum. The complaints had been going on for a year. Ten months ago, he was examined and prescribed an antibiotic, which reduced his symptoms for some time. Personal history includes treatment for narrow spinal canal and chronic iron deficiency. Requested records reveal that the patient was referred from an emergency department to gastroenterology in the same building ten months ago. The examination at that time, rectoscopy and rigid endosonography, revealed a rectal ulcer and proctitis. Biopsies were taken, but no smears were obtained. The fact that the man had sex with men is mentioned in the investigation report.

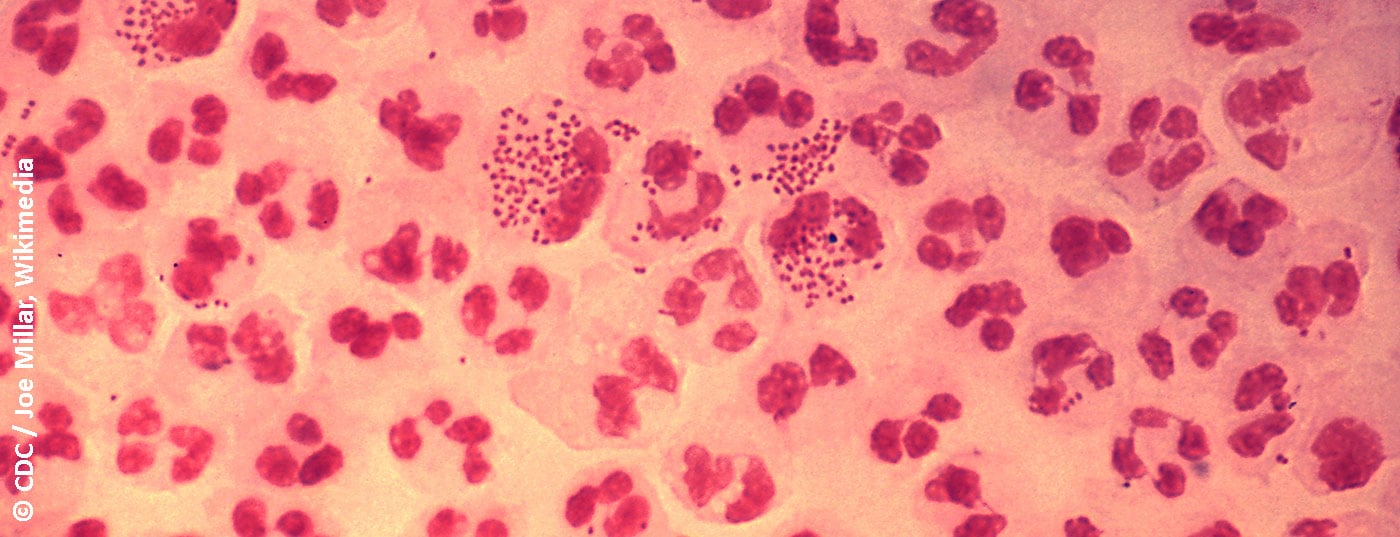

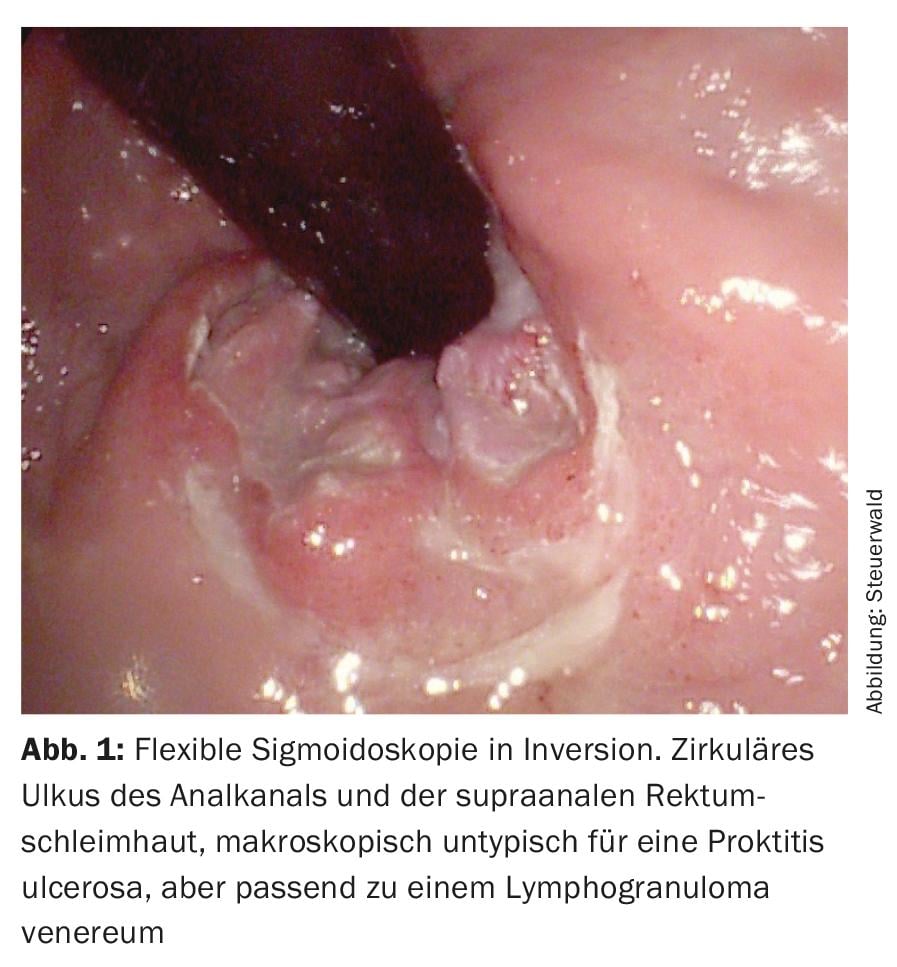

Anoscopy and flexible sigmoidoscopy performed at our institution (Fig. 1) shows an ulcer in the anal canal, corresponding to either a primary effect of lues or a lymphogranuloma venereum. The smear is positive for N. gonorrhoeae and Chlamydia trachomatis, serovars L1, L2, L3, and L2B. After therapy with 2× 100 mg doxycycline, the patient is symptom-free after a few weeks. Subsequent controls reveal condylomata acuminata treated with the argon beamer, since then without recurrence. One year later, self-referral again after sexual contact with a man diagnosed with gonorrhea. The swabs (oral, anal, urethral) in our patient were negative, preemptive treatment with 2 g Rocephin® i.m. was given.

A second case: a 48-year-old man assigned for chronic proctitis. For two months discharge of mucus and blood per anum, dorsally there is a strongly dolente mariske. Similar episode four years ago, then assessed as ulcerative proctitis. HIV infection known for five years, treated for eight months with now normal CD4+ cell count and suppressed HIV. The patient had unprotected sex with men.

Anorectoscopy shows a highly florid distal proctitis with large skin folds, partly macerated. The smears are positive for N. gonorrhoeae and C. trachomatis. Their differentiation results in serovar L2b, proving the diagnosis of lymphogranuloma venereum. The healing process is slow. After a second treatment with 2× 100 mg doxycycline for three weeks, the proctitis heals completely. Persistent mariscs are resected at the patient’s request. One year later, re-presentation with the picture of LGV recurrence confirmed by PCR and again successfully treated with doxycycline.

Medical history

In newly diagnosed proctitis in men, the possibility of a sexually transmitted infection should be considered. The physician must be aware that homosexuality means different things: sexual behavior, sexual preference, and identity. The relevant question here is, “Have you had sex with a man in the past?” Now how do you tactfully get to this question in a conversation? One way is to mention that sexually transmitted pathogens can cause disease patterns similar to that of “our” patient. It should then be noted that it is difficult, yet important, to talk about sex, followed by a statement that the physician does not value sexual activity or communicable diseases. For example, by saying, “Sex is part of a healthy life, everyone practices it in their own way.” Further, it should be stated that such diseases are common among men who have had sex with men and that they can be treated efficiently. The patient should be given the opportunity to respond to these statements by pauses. An empathic and tactful approach to conversation builds trust and breaks down barriers. If the above question can be answered, you are a good deal closer to a diagnosis. Dodging the less “tricky” chronic autoimmune-mediated intestinal diseases will result in missing the diagnosis.

Diagnostics

The history and clinical examinations must be supplemented by intraanal swabs for pathogen detection. The technique is simple: carefully insert a swab rotating 2-4 cm into the anus and swab the anal wall in several places. The patient can also do this himself after instruction. Additional swabs are taken urethrally and pharyngeally. For cost reasons, the swabs can be pooled, i.e. the three swabs can be sent in one sample vessel. PCR for the most common pathogens such as Chlamydia trachomatis, N. gonorrhoeae, and T. pallidum, plus culture and resistance testing for N. gonorrhoeae should be required. Less common causative agents of infectious proctitis include herpes simplex and, with a history of travel, amoebae and Giardia lamblia. According to the manufacturer, PCR is usually not approved for rectal swabs, but it has been superior to all other methods in studies. Serologies for Chlamydia trachomatis and N. gonorrhoeae are not useful because of poor sensitivity and specificity. As with all sexually transmitted diseases, additional serologies for HIV, hepatitis A, B, and C, and T. pallidum should be prescribed.

It is critical that these results be explained to the patient in a timely manner and copied to other physicians involved. Therapy needs monitoring and debriefing to ensure adherence and prevent recurrences. During a follow-up consultation, prophylaxis should be addressed, namely “safer sex,” regular testing, and PrEP (HIV chemoprevention).

Therapy

The therapy of chlamydial, gonococcal or syphilitic proctitis is basically identical to that of a genital infection. In chlamydia, several serovars are distinguished genotypically, which differ in tissue tropism and are treated differently. Serovars A-C cause trachoma, and serovars D-K cause urethritis, cervicitis, pharyngitis, and rarely proctitis. Serovars L1 to L3 cause proctitis and genitoanal infections such as lymphogranuloma venereum (LGV). Chlamydia serovars A-K are treated with doxycycline 100 mg twice daily for one week. Chlamydia serovars L1 to L3 must be treated with doxycycline 2× 100 mg for three weeks. Serovar determination means additional work, which is why some laboratories do not offer these analyses. In ignorance of the serovars, the three-week therapy is indicated because serovars L1 to L3 are more common, especially in proctitis.

Several treatment recommendations exist for the treatment of N. gonorrhoeae. These result from consideration of the different resistance epidemiology (regions, risk groups). Dual therapy with a single dose of ceftriaxone 1 g i.m. (or i.v.) plus azithromycin 1.5 g p.o. is currently recommended. (or i.v.) plus azithromycin 1.5 g p.o. is recommended.

Syphilis is treated with benzathine penicillin 2.4 IU i.m. ventrogluteally. For early syphilis (infection <1 year), a single injection is sufficient; for late syphilis or if the duration of the disease is unknown, repeat the injection on days eight and 15.

Sexual partners in the past six months should be tested for urethral, rectal, and pharyngeal infections, if possible, and antibiotic treatment should be given if the pathogen is positive. If testing is not possible, therapy can be given without prior diagnosis.

Discussion

Common to both cases is that the proctitides were judged to be noninfectious, even though both patients had told their physicians that they had sex with men. However, both patients felt unappreciated, which prevented more “detailed” addressing of past sexual encounters. Inherent in both cases is that they were multiple infections, and also that both men presented again after a year with a new infection.

Sexually transmitted diseases are common among men who have sex with men (MSM). The risk of these bacterial infections has increased in recent years. The reason for this is that for some years now HIV transmission can be prevented by chemoprevention (PrEP) and patients with HIV infection are not infectious under therapy. Due to a change in risk perception, therefore, the need for the use of a condom to protect against HIV infection during sex outside of monogamous relationships no longer applies. Although condoms do not prevent the transmission of classic venereal infections, they do reduce their spread. The increase in “classic” sexually transmitted diseases has also been documented in Switzerland.

Such diseases are asymptomatic in the majority of MSM. In patients with proctitis, the diagnosis may be missed because clinic and work-up results (anoscopy, sigmoidoscopy) are mistakenly interpreted as chronic inflammatory bowel disease. A series from Israel describes 16 patients at one center in whom initial misdiagnosis resulted in a delay in correct diagnosis of one to 24 months. Infections with chlamydia, N. gonorrhoeae, and T. pallidum are chronic and are associated with up to a ninefold higher transmission rate of HIV infection.

Conclusion

Sexually transmitted infections of the anorectum can deceptively mimic inflammatory bowel disease (Crohn’s disease or ulcerative colitis). Clinical and endoscopic diagnostics sometimes do not allow the distinction between infectious and chronic autoimmune genesis. Crucial to diagnosis is a good doctor-patient relationship based on trust and empathy. The anamnesis must be taken without judgment, tactfully and empathically. Diagnosis is simple: one swab each for Neisseria gonorrhoeae, Chlamydia trachomatis and Treponema pallidum (PCR), taken from the anus, meatus urethrae and throat, sent in a swab kit. Therapy can be started immediately if there is a reasonable clinical suspicion or after the results are obtained if there is any uncertainty. Depending on the epidemiology (travel history), the diagnostics for amoebae and Giardia lamblia must be extended. In the case of painful ulcers of the anoderm, herpes affection should be considered.

Serological diagnostics for HIV, T. pallidum, hepatitis A, B, and C should be performed during treatment. Patients must be educated regarding transmission, partner clarification, and prevention of recurrence of sexually transmitted diseases. Very critical is stringent scheduling of checks (serology, clinic) and showing patients where to go for questions regarding sexual health if this is not possible in the treating physician’s office. The care of these patients requires interdisciplinary collaboration between the disciplines of family medicine, dermatology/venerology, gastroenterology, and infectious diseases.

Take-Home Messages

- Sexually transmitted infections of the anorectum can deceptively mimic inflammatory bowel disease (Crohn’s disease or ulcerative colitis).

- Crucial to diagnosis is a trusting and empathetic doctor-patient relationship.

- In principle, diagnosis is simple: swabs for Neisseria gonorrhoeae, Chlamydia trachomatis and Treponema pallidum (PCR) from the anus, meatus urethrae and pharynx, sent in a swab kit. If there is a corresponding travel history, the diagnosis must be extended to include amoebae and Giardia lamblia.

- Therapy can be given immediately if there is a reasonable clinical suspicion or after the results are obtained if there is any uncertainty.

- Patients are to be educated regarding transmission, partner clarification, and prevention of recurrence of sexually transmitted diseases.

Further reading:

- De Vries HJ: Sexually transmitted infections in men who have sex with men. Clinics in Dermatology 2014; 32: 181-188.

- Lourtet Hascoet J, et al: Clinical diagnostic and therapeutic aspects of 221 consecutive anorectal Chlamydia trachomatis and Neisseria gonorrhoeae sexually transmitted infections among men who have sex with men. International Journal of Infectious Diseases 2018; 71: 9-13.

- Hoentjen F, Rubin DT: Infectious Proctitis: When to Suspect It Is Not Inflammatory Bowel Disease. Dig Dis Sci 2012; 57: 269-273.

- Levy I, et al: Delayed diagnosis of colorectal sexually transmitted diseases due to their resemblance to inflammatory bowel diseases. International Journal of Infectious Diseases 2018; 75: 34-38.

- Farfour E, et al: Increase in sexually transmitted infections in a cohort of outpatient HIV-positive men who have sex with men in the Parisian region. Médecine et maladies infectieuses 2017; 47: 490-493.

HAUSARZT PRAXIS 2019; 14(1): 17-19