Minimally invasive and robotic approaches, interdisciplinarity, and centralization have transformed the surgical treatment of tumor patients in recent years. The hospital stay can also be optimized. Review of developments in recent years.

Surgical tumor removal has always been an essential part of cancer treatment. For many malignancies, the local control that can be achieved with this method is the only starting point for a permanent cure. With this in mind, attempts were often made in earlier years to improve outcomes by increasing the radicality of surgery. This often meant mutilating surgeries without consideration of function-preserving options. This was also associated with increased morbidity or even mortality.

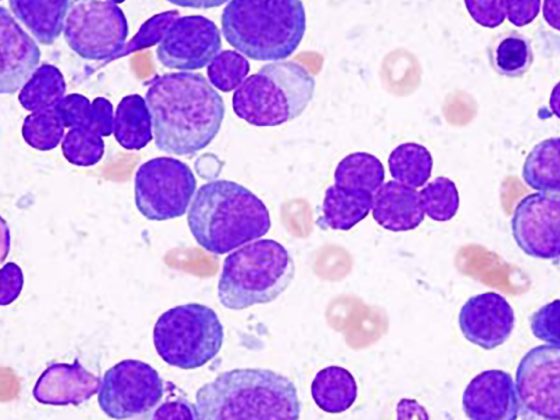

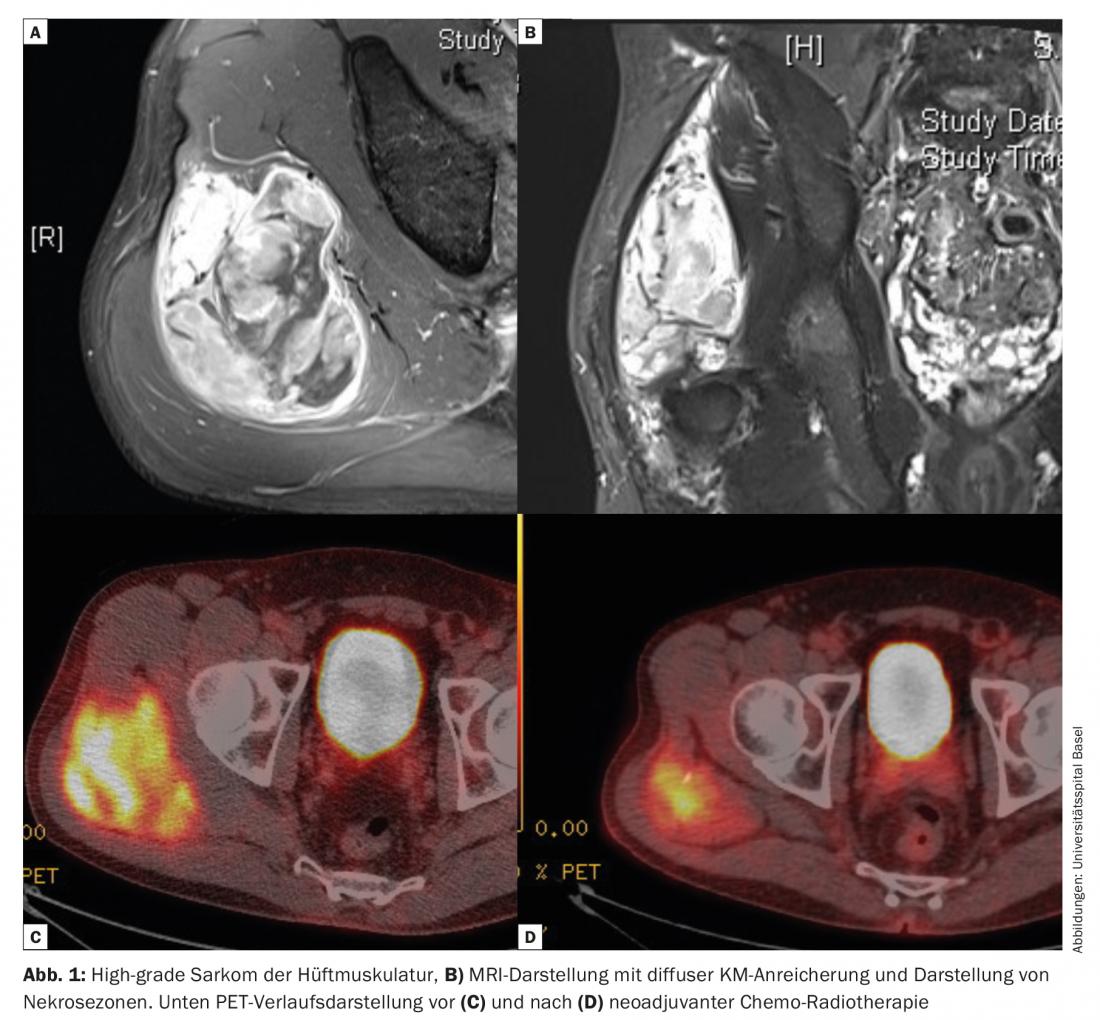

Nevertheless, oncologic outcomes were inadequate in many cases. Only the increasing understanding of the mechanisms of metastasis and the realization that many cancers can already be considered systemic diseases at the time of diagnosis have led to the establishment of multimodal therapy concepts. In many cases, it was possible to simultaneously reduce the surgical radicality without compromising the results. This becomes clear in the treatment of soft tissue sarcomas. The combination of surgery and radiation has largely displaced amputation as a surgical therapy (Fig. 1).

Growing understanding of disease and innovation crucial for change

In no example is the change in surgical and also in interdisciplinary treatment strategy more evident than in breast carcinoma. The development of surgical techniques ranges from Rotter-Halsted radical mastectomy to radiologically assisted targeted tumorectomy with greatest possible preservation of breast tissue and simultaneous plastic surgical reconstruction. The “sentinel node” concept, introduced in the 1990s first in melanoma and then in breast carcinoma, now allows for improved axillary lymph node staging with reduced morbidity.

This change in the role of surgery in the treatment concept is, of course, not only based on improved surgical technique. The basic prerequisite is, on the one hand, the increasingly better understanding of tumor biology in the various stages of the disease in conjunction with significantly improved diagnostic possibilities. In addition, developments in systemic therapy in the form of chemotherapy, hormone therapy, and most recently immunotherapy have enabled tremendous advances, as have technological developments in radiotherapy.

Surgical oncology is always in the context of advances in surgery in general. From the multitude of developments in surgical technology and improved interdisciplinary treatment concepts, some aspects that have also changed the surgical therapy of tumor patients will be highlighted in the following.

Minimally invasive surgery

One of the major technological developments in surgery in recent decades has been the introduction of minimally invasive surgery. The primary goal is to reduce surgical trauma and thus speed patient recovery with less morbidity. However, this was countered by concerns that this technique would compromise oncologic quality of surgery. In particular, a lower number of lymph nodes removed and a higher rate of incomplete resections (R1/R2) were feared. This issue has been best studied in colorectal carcinoma. A number of high-profile international prospective studies (e.g., CLASSIC, COLOR) have now clearly demonstrated that minimally invasive surgery is at least equivalent to open surgery in terms of oncologic treatment outcome. Analogous data are now available for other tumor entities such as gastric or esophageal carcinoma. Today, it can be assumed that with appropriate surgical expertise, the choice of surgical technique has no negative influence on the quality of treatment. And especially in esophageal cancer, the reduction of morbidity compared to open surgery is of enormous importance. Therefore, minimally invasive thoracoscopic esophagectomy is now a standard procedure in most centers.

Robot assisted surgery

The development of robot-assisted surgery is heading in the same direction. It has been firmly established in prostate cancer surgery for years. Despite concerns about increased costs, this technique is gaining acceptance for other oncologic surgeries. This is by no means just a matter of supposed progress through the technology of the feasible. Increased freedom of movement due to improved manipulators and superior optical imaging in confined anatomical regions (rectal resection, esophageal resection) are advantages that many surgeons advocate for this technique. And anticipated developments with integration of navigation capabilities (e.g., fluorescence-guided) and virtual overlay of real-time anatomy with cross-sectional imaging data will be additional benefits of this technology.

Extending the surgical boundaries

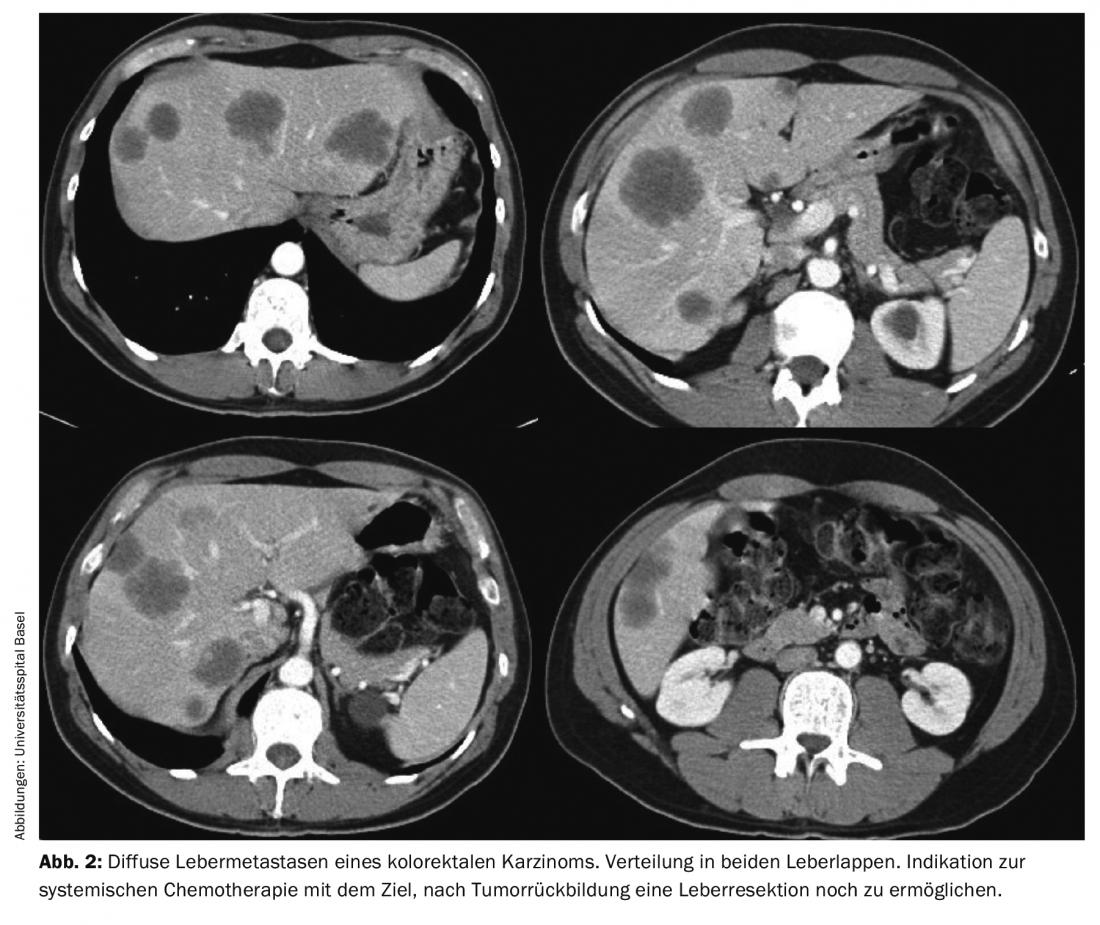

Improved surgical techniques and the interaction with modern anesthesia and intensive care medicine allow us to constantly push the boundaries of surgery. Developments in modern liver surgery under the influence of experience from transplantation surgery allow that even patients with extensive liver metastases can still be submitted to curative resection in some cases. In this regard, extended liver resections, multi-stage resections after portal vein embolization, and combinations of resections and ablative procedures (radiofrequency ablation or cryotherapy) are now regularly used. Especially in these patients, close interdisciplinary coordination with oncology often takes place in order to first achieve tumor remission through system therapy, which then still makes resection possible (Fig. 2).

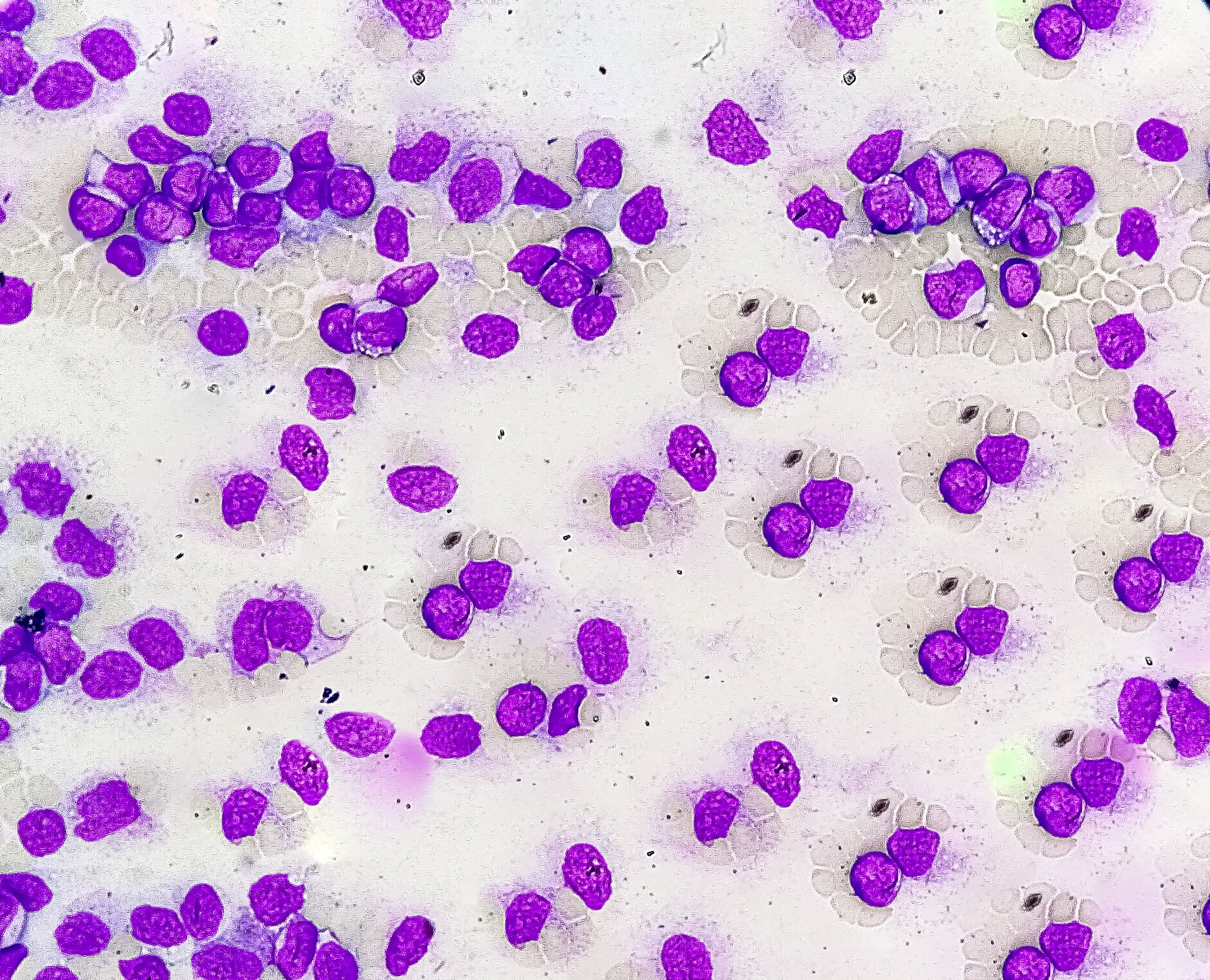

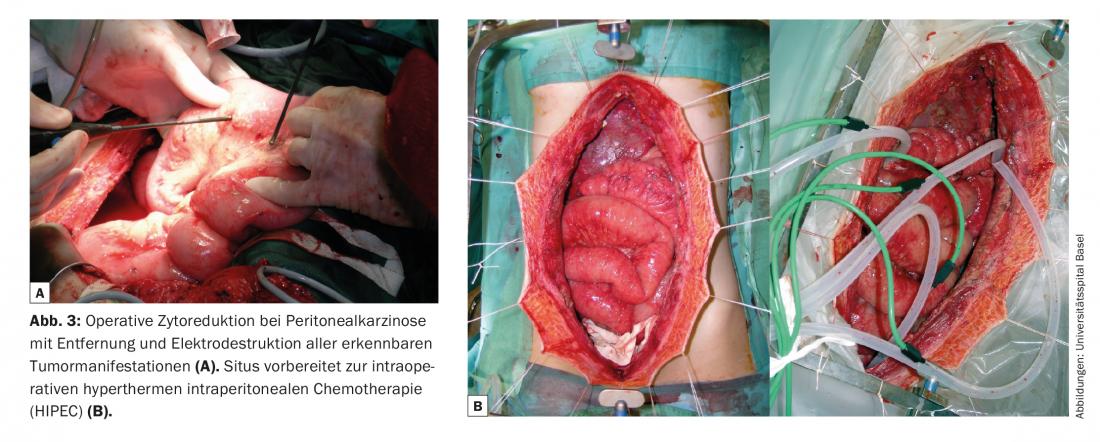

Extensive surgery in metastatic situations was previously considered obsolete. Based on the results of radical tumor debulking of the peritoneum in pseudomyxoma, it was shown that this is also an effective therapeutic option for carcinoma diseases with peritoneal carcinomatosis. However, the prerequisite is that cytoreductive surgery achieves macroscopic tumor freedom or that only very small tumor nodules remain. Combination with hyperthermic intraperitoneal chemotherapy (HIPEC) (Fig. 3) can control the residual tumor burden, in some cases over the longer term. After complete tumor resection for peritoneal carcinomatosis from colorectal carcinoma, 5-year survival rates of up to 40% have been described, which is similar to the results after resection of liver metastases.

Centralization

Comprehensive surveys of hospital data were able to show a clear correlation between case numbers and outcome quality, as measured by mortality after surgery. This relates both to the absolute number of patients treated and operated on at a hospital with a specific diagnosis and to the case numbers of individual surgeons. In addition, there are clear correlations to infrastructural requirements and treatment processes (team performance). Thus, in principle, the conditions are in place to improve surgical outcomes through centralization measures with a reduction in perioperative morbidity and mortality. Based on this argumentation, a regulation of important oncologically relevant operations is also taking place in Switzerland under the heading HSM (Highly Specialized Medicine). This includes liver and pancreas resections, esophageal resections, and deep rectal surgeries as well. However, in addition to purely number-driven centralization, it is of high importance for the respective hospitals to coordinate oncology treatments in a strong interdisciplinary network. Only in this way can the hoped-for results of these measures actually be achieved.

Optimized hospital stay

In the 1990s, concepts for faster recovery of patients after surgery were developed under the keyword “fast track surgery”. The goal was to shorten the postoperative stay and reduce the complication rate. Of course, this is also associated with a reduction in costs. The essential content of these programs, now known as ERAS (“enhanced recovery after surgery”), is a multidisciplinary approach with a standardized patient pathway. Improvements can be achieved, particularly in the area of colon surgery, by adherence to a set of evidence-based criteria. The most important factors here are minimally invasive surgery whenever possible, avoidance of gastric tubes and drains, avoidance of morphine-based analgesia, intraoperative fluid restriction, rapid mobilization of patients postoperatively, and unrestricted food intake even after bowel resections. Preoperative education and patient involvement in this program is at least as important. For this purpose, they are accompanied pre- and post-operatively by specially trained nursing staff. With the help of this structured treatment protocol, for example, the postoperative length of stay after colon resection could be reduced by five days in our hospital. In addition to colorectal surgery, there are now established ERAS programs for a number of major and complex procedures, including esophageal and pancreatic resections.

Interdisciplinarity

However, a crucial prerequisite for modern surgical oncology, in addition to the application of advanced surgical techniques, is above all a high level of understanding of the results in oncology that can only be achieved on an interdisciplinary basis. Neoadjuvant therapy concepts, as used today in a variety of malignancies such as esophageal and gastric carcinoma, rectal carcinoma, sarcoma surgery, and other tumors, place special demands on surgery. Only through close interdisciplinary coordination and careful surgical technique is it possible to achieve good results with low complication rates even in these patients.

Surgery also often requires a multidisciplinary approach, which must be a given for surgical oncologists today. It can no longer be about the “one does it all” view. Rather, the competencies must be bundled for the patients. Complex interventions such as multivisceral tumor debulking in ovarian cancer, resections of retroperitoneal and intra-abdominal sarcomas, oncoplastic surgery in breast cancer, resection and plastic reconstruction in bone and soft tissue sarcomas therefore also require appropriate infrastructures.

Take-Home Messages

- Surgical oncology is always in the context of advances in surgery in general.

- Minimally invasive and robotic approaches, but also the interaction with modern anesthesia and intensive care, interdisciplinarity and centralization measures (with a corresponding reduction in perioperative morbidity and mortality) have changed the surgical therapy of tumor patients.

- Pre- and postoperative hospital stay can also be optimized under the term ERAS (“enhanced recovery after surgery”) with shortened length of stay and reduced complication rate.

Further reading:

- Ljungqvist O, Scott M, Fearon KC: Enhanced Recovery After Surgery: A Review. JAMA Surg 2017 Mar 1; 152(3): 292-298.

- Hoffmann H, Kettelhack C: Fast-track surgery–conditions and challenges in postsurgical treatment: a review of elements of translational research in enhanced recovery after surgery. Eur Surg Res 2012; 49(1): 24-34.

- Theophilus M, Platell C, Spilsbury K: Long-term survival following laparoscopic and open colectomy for colon cancer: a meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Colorectal Dis 2014 Mar; 16(3): 75-81.

- Fleshman J, et al: Effect of Laparoscopic-Assisted Resection vs Open Resection of Stage II or III Rectal Cancer on Pathologic Outcomes: The ACOSOG Z6051 Randomized Clinical Trial. JAMA 2015 Oct 6; 314(13): 1346-1355.

- Buunen M, et al: Survival after laparoscopic surgery versus open surgery for colon cancer: long-term outcome of a randomised clinical trial. Lancet Oncol 2009 Jan; 10(1): 44-52.

- Okusanya OT, et al: Robotic assisted minimally invasive esophagectomy (RAMIE): the University of Pittsburgh Medical Center initial experience. Ann Cardiothorac Surg 2017 Mar; 6(2): 179-185.

- Luketich JD, et al: Minimally invasive esophagectomy: results of a prospective phase II multicenter trial-the eastern cooperative oncology group (E2202) study. Ann Surg 2015 Apr; 261(4): 702-707.

- Spanjersberg WR, et al: Fast track surgery versus conventional recovery strategies for colorectal surgery. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2011 Feb 16; (2): CD007635.

- Bushati M, et al: The current practice of cytoreductive surgery and HIPEC for colorectal peritoneal metastases: results of a worldwide web-based survey of the Peritoneal Surface Oncology Group International (PSOGI). Eur J Surg Oncol 2018 Jul 20. pii: S0748-7983(18)31182-X [Epub ahead of print].

- Chua TC, et al: Early- and long-term outcome data of patients with pseudomyxoma peritonei from appendiceal origin treated by a strategy of cytoreductive surgery and hyperthermic intraperitoneal chemotherapy. J Clin Oncol 2012 Jul 10; 30(20): 2449-2456.

- Birkmeyer JD, et al: Hospital volume and surgical mortality in the United States. N Engl J Med 2002 Apr 11; 346(15): 1128-1137.

- Reames BN, et al: Hospital volume and operative mortality in the modern era. Ann Surg 2014 Aug; 260(2): 244-251.

- Finlayson EV, Goodney PP, Birkmeyer JD: Hospital volume and operative mortality in cancer surgery: a national study. Arch Surg 2003 Jul; 138(7): 721-725.

- Adam R, et al: Resection of colorectal liver metastases after second-line chemotherapy: is it worthwhile? A LiverMetSurvey analysis of 6415 patients. Eur J Cancer 2017 Jun; 78: 7-15.

- Bonney GK, et al: Role of neoadjuvant chemotherapy in resectable synchronous colorectal liver metastasis; An international multi-center data analysis using LiverMetSurvey. J Surg Oncol 2015 May; 111(6): 716-724.

InFo ONCOLOGY & HEMATOLOGY 2018; 6(6): 21-24.