Dissociative disorders are characterized by a highly heterogeneous presentation. What are the diagnostic tools? How do those affected experience their disease? And what to look for in the treatment of dissociative disorders?

“Like a globe of mercury, it escapes the grasp” – Ilza Veith’s metaphor for hysteria is still valid today [1]; the “elusive” is also reflected in the conceptual variety. The former name “hysteria” has been replaced and the multifaceted clinical picture is now internationally standardized in the ICD-10 under “dissociative disorders”. Nevertheless, different terms continue to be used: Neurologists speak of “functional disorders”, general practitioners of “psychogenic” or “non-organic disorders”, the English-language literature of “somatoform disorders”. In neuroscience research, “functional neurological disorders” is common. The psychoanalytic term “conversion disorder” or “conversion neurosis” is also still occasionally used.

A modern classification could help, e.g., a division of dissociative disorders into their three manifestations, somatoform, psychoform, and structural dissociation. The latter would include multiple personality as well as “ego states” following severe trauma. Currently, symptom-based attribution seems to be more prevalent, which favors a fractionalized view, i.e., split into different medical specialties.

What are dissociative disorders?

Whoever deals with this ancient – first descriptions can be found in Egyptian papyri as early as the second millennium B.C. – and yet ever new clinical picture encounters a fascination: How does a “transfer” of psychological experience into physical symptoms occur? Or does a holistic reality apply, which is manifested in this symptom formation?

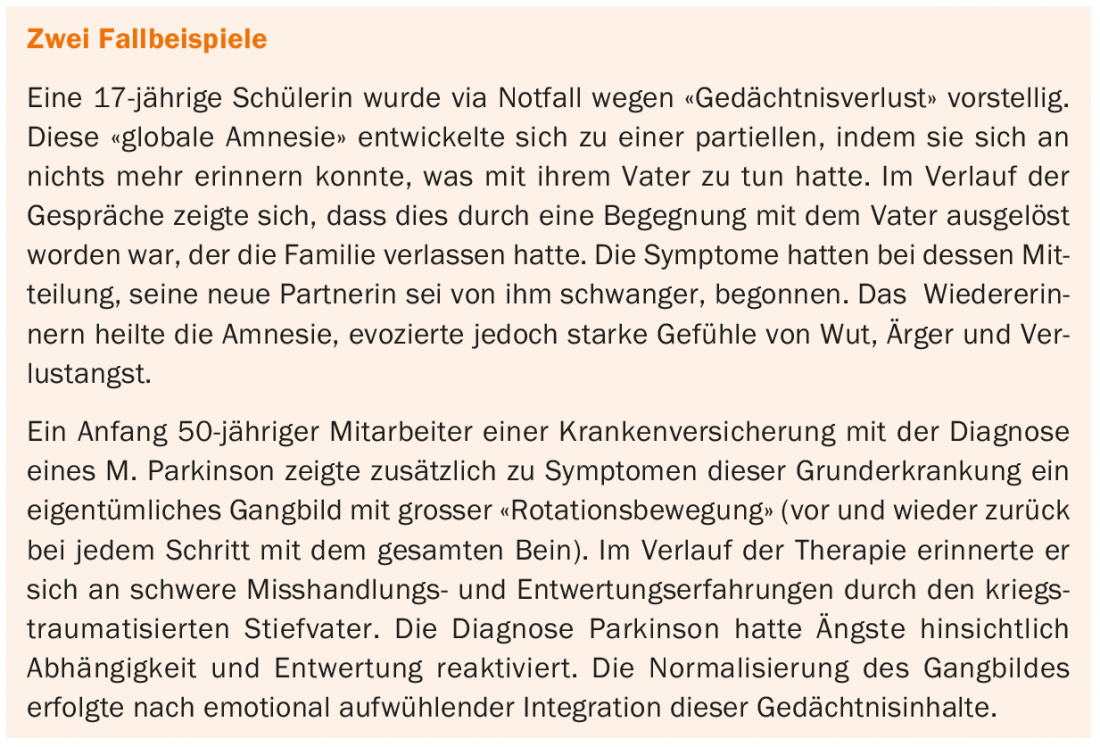

According to ICD-10 (F44.0-9), there are problems with integration of memories, sense of identity, immediate sensation, and control of body movements. For the diagnosis, the exclusion of an organic cause and evidence of a psychological causation of the symptoms is required. In addition, there are clinical characteristics. If none of these three criteria are met, the diagnosis should not be made. In the absence of evidence of psychological causation, the diagnosis is only tentative and the search for physical and psychological aspects must continue. The manifestations range from amnesia or stupor to movement disorders or seizures. A careful history and a detailed clinical examination are important for establishing the diagnosis. The latter focuses on the careful clarification of a possible organic cause or signs of a dissociative genesis. Such include discrepancies in the severity of impairment (dependent on observation) or the Hoover sign, in which innervation is detected by indirect testing, as well as other clinical characteristics such as symptom presentation that corresponds to the ideas of the affected person but not to neuroanatomical reality. Two case studies are described in the box, which show the complexity of the clinical picture.

Data on the frequency of dissociative disorders are uncertain. Studies show a prevalence between 1.4-4.6% and a sex ratio of 1(m):3(w). The disease often begins in the third decade of life, and the course may be chronic or episodic. How close to consciousness the symptoms are seems to fluctuate. The English surgeon James Paget wrote in 1873: “She says, as all such patients do, ‘I cannot’ it looks like, ‘I will not’ but it is ‘I cannot will'” (quoted from [2]).

The differential diagnosis includes somatic diseases and, among others, images such as simulation and Munchausen’s syndrome.

Self-experience

Those affected usually report little about their subjective experience during the development of their symptoms. However, the descriptions of articulate authors during their own dissociative symptomatology give a valuable impression. In his self-description “A Leg To Stand On” (1984), the neurologist and author Oliver Sacks describes a dissociative disorder of which he was not aware from the subjective perspective: “What was now becoming frightfully, even luridly, clear was that whatever had happened was not just local, peripheral, superficial […] This was radical, central, fundamental. What seemed, at first, to be no more than a local, peripheral breakage […] now showed itself in a different, and quite terrible, light – as a breakdown of memory, of thinking, of will – not just a lesion in my muscle, but a lesion in me” (quoted from [2]).

Writer Siri Hustvedt summarized her experience of a dissociative tremor in the essay “The Shaking Woman or A History of My Nerves.” She prefaces her self-description with a quote from Emily Dickenson: “I felt a cleaving in my Mind – As if my Brain had split – I tried to match it – Seam by Seam – But could not make it fit.” In addition, she reports in a technical article [3].

Imaging

By the turn of the millennium, technology and methodology were not yet mature and the editorial of the journal Brain rightly stated in 2001: “The findings of these few studies are intriguing rather than conclusive” [4]. However, for some years now, there has been relevant progress. A comparison of imaging in dissociative movement disorders with hypnosis-induced paresis showed hyperactivity of the ventromedial prefrontal cortex (VMPFC) in dissociative disorders but not in hypnosis [5]. The VMPFC mediates access to self-representation and integrates memory content with affective relevance. The authors of the study concluded, “Conversion deficits […] might promote certain patterns of behaviors in response to self-relevant emotional states.” This correlate in imaging is consistent with clinical experience. Today, several research groups are working on the subject, including at the Inselspital in Bern.

Genetics and epigenetics

A twin study published in 1998 with 177 monozygotic and 152 dizygotic twin pairs concluded regarding genetic factors and dissociative disorders: “Significant genetic correlations […] were found between the DES scales and DAPP-BQ cognitive dysregulation, affective lability, and suspiciousness, suggesting that the genetic factors underlying particular aspects of personality disorder also influence dissociative capacity” [6].

New insights are due to epigenetics. Thus, changes in gene expression appear to occur via methylation and demethylation. In the field of stress response, methylation at the FKBP5 allele seems to be particularly relevant and also important for intergenerational effects [7]. Thanks to epigenetic research, the complex interplay of environmental factors and genetics is increasingly well understood.

Vulnerability-stress model, psychodynamic models, new concepts.

With regard to the etiology of dissociative disorders, the vulnerability-stress model postulated a genetic predisposition with increased suggestibility and early traumatizing experiences. The older psychoanalytic concepts saw dissociation as a defense mechanism in the case of conflictual impulses. In this process, the integrating function of the “I” would be cancelled and subjectively unbearable contents would be neutralized by splitting them off.

Contemporary psychodynamic concepts assume less unconscious conflict and more emotional dysregulation in the area of self-perception and self-expression [8].

In a recent review, functional neurological symptoms are interpreted as forms of complex affective responses to stress that are related to learned emotional behavior and a diminished ability to perceive one’s own internal emotional processes [9].

Treatment

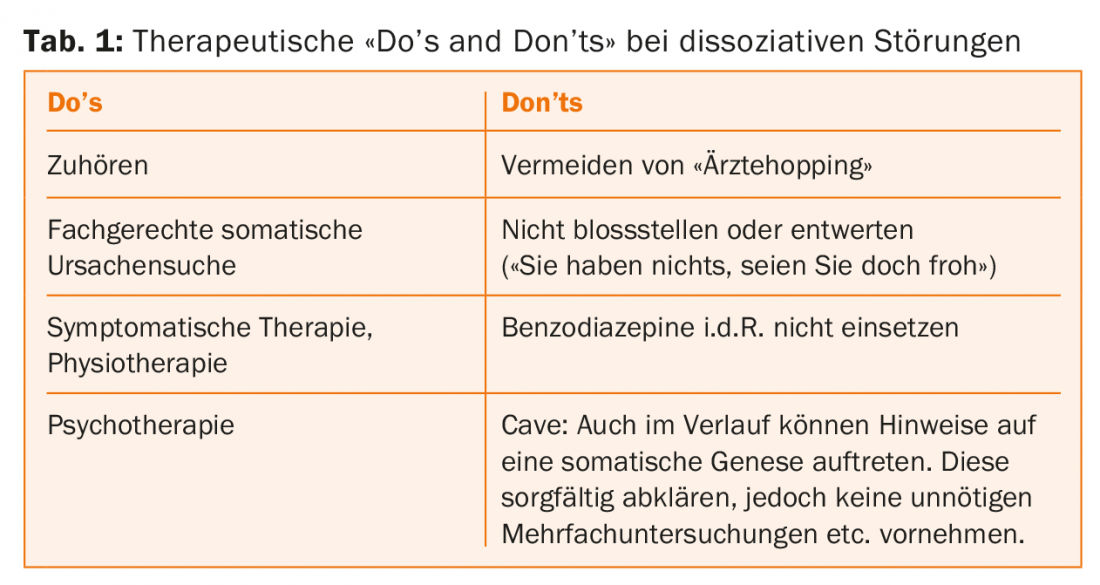

Today, psychotherapeutic treatment is usually combined with symptomatic therapy, and physiotherapy is of great importance in dissociative movement disorders. Relaxation techniques are also used. Suggestive measures are often effective. In our own work on stressors during childhood development (with matched pairs and investigator blinded to seizure genesis), we found no difference between subjects with epileptic and nonepileptic dissociative seizures. Both groups were highly loaded in this regard. However, the placebo infusion had resulted in seizure freedom in the majority of those with dissociative seizures, even at follow-up six months later [10].

Premature confrontations carry the risk of treatment discontinuation and “physician hopping.” It is important to explain examination results in a reassuring and not devaluing way, combined with an indication of a good prognosis.

Psychotherapeutic treatment offers the chance of deepened (self-)perception and integration of emotionally stressful aspects. Ideally, a personal maturation process with integration of the dissociated parts takes place. The basis of therapy is the therapeutic relationship, therefore a therapeutic space is designed in the first phase of treatment. An open, non-judgmental attitude and consideration of basic psychological needs such as self-esteem protection are essential. In this first phase, close listening is important, with symptom elicitation also in the emotional and interactive context. In further treatment, the symptom development is understood and clarified in more depth. These include body awareness, emotions, and present-day relationships. The narrative of inner life is understood against the background of real life. Sometimes traumatic experiences that are emotionally present in the present can be remembered and spoken for the first time. The final phase is predominantly about stability and integration.

Therapy research is methodologically difficult in this heterogeneous picture with large interindividual variability. Meta-analyses are scarce but provide evidence of effectiveness [11].

Drug therapy is not indicated, except in cases of marked comorbidity with anxiety disorder or depression. The possible adverse effects are otherwise not offset by any proven benefit. The experience of self-efficacy may be hindered by (mis)attribution to medication and medical treatment. In addition, the induced emotional distancing can make it more difficult to update the problem and subsequently solve it (Table 1).

Personal conclusion

In my first months as a young resident in a neurology department, a senior physician used the word “hysteroepilepsy” to describe the seizures of a young, slightly less intelligent man. What was meant was the occurrence of epileptic and psychogenic seizures. But while for him the case seemed solved with this diagnosis, for me the questions began: Why? And how can we help him? Today, after almost 30 years and many accompaniments of affected persons, I still cannot give an affirmative answer that is valid for all. But I was allowed to learn a lot, each encounter and life story was unique. Today I believe that the dissociative disorders become understandable only by overcoming the dual thinking.

In dealing with the patients concerned, it seems essential to me to respectfully and attentively explore their personal history, their outer and inner life story, and to “listen in” not only to what is told, but also to what is omitted. The patient’s reliable self-esteem protection is necessary for a trusting therapeutic relationship. He must feel that his physical self-perception, as well as his entire person, is accepted not judgmentally, but with unconditional attention. Only in this way can powerful feelings of helplessness, being at the mercy of others, shame or existential fear be revealed. The transformative power of these feelings in forgetting, but also in remembering, thus becomes accessible again. Remembering, combined with self-acceptance and being aware of the past, allows for a more complete self-image. Being connected to one’s own hurts and needs facilitates fully recognizing the needs of others. This awareness, if successful, is the basis of a new (not only symptom) freedom.

Take-Home Messages

- Dissociative disorders are classified in ICD-10 in chapter F44. However, the heterogeneous terminology between the medical disciplines with terms such as “functional disorders”, “psychogenic disorders”, in the English-speaking world “somatoform disorders”, and the multiform expression make a uniform view and a good interaction between research and clinic difficult.

- Diagnostic guidelines call for exclusion of an organic cause, clinical characteristics, and evidence of psychological causation of symptoms.

- Current findings from psychodynamics, imaging, and epigenetics are complementary and evolving toward a deeper, holistic understanding.

- Therapy includes a symptomatic approach with physiotherapy for dissociative movement disorders and psychotherapy. The latter offers the possibility of integration, self-acceptance and transformation.

Literature:

- Veith I: Hysteria. The History of a Disease. Chicago: The University of Chicago, 1965.

- Stone J, Perthen J, Carson AJ: Review. “A Leg to Stand On” by Oliver Sacks: a unique autobiographical account of functional paralysis. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry 2012; 83(9): 864-867.

- Hustvedt S: I wept for four years and when I stopped I was blind. Neurophysiol Clin 2014; 44(4): 305-313.

- Ron M: Explaining the unexplained: understanding hysteria. Brain 2001; 124(6): 1065-1066.

- Vuilleumier P: Brain circuits implicated in psychogenic paralysis in conversion disorders and hypnosis. Neurophysiol Clin 2014; 44(4): 323-337.

- Jang KL, et al: Twin study of dissociative experience. J Nerv Ment Dis 1998; 186(6): 345-351.

- Klengel T et al: Allele-specific FKBP5 DNA demethylation mediates gene-childhood trauma interactions. Nature Neuroscience 2013; 16(1): 33-41.

- Sattel H, et al: Brief psychodynamic interpersonal psychotherapy for patients with multisomatoform disorders: randomised controlled trial. Br J Psychiatry 2012; 200(1): 60-67.

- Sojka P, et al: Processing of emotion in functional neurological disorder. Front Psychiatry 2018; 9: 479.

- Berkhoff M, et al: Developmental Background and Outcome in Patients with Nonepileptic Versus Epileptic Seizures: A Controlled Study. Epilepsia 1998; 39(5): 463-469.

- Koelen J. et al: Effectiveness of psychotherapy for severe somatoform disorder: meta-analysis. Br J Psychiatry 2014; 204(1): 12-19.

InFo NEUROLOGY & PSYCHIATRY 2018; 16(6): 24-27.