What are the new findings concerning diagnostic classification systems? Pros and cons of categorical vs. dimensional approaches. How can neurobiological findings be integrated into diagnostic and therapeutic concepts? The problem of the implementability of neurobiological research findings. What is the current state of evidence-based treatment? Explanation of the therapy scheme according to the S3 guideline. The tension between the current legal situation and the state of medical knowledge.

Globally, substance dependence disorders contribute significantly to health harms (“Global Burden of Disease”) [1]. In Switzerland, alcohol and tobacco are the leading cause of preventable premature deaths, with a large proportion of the population engaging in low-risk consumption [2]. Whether occasional use develops into dependence with psychological dysfunction and limitations in everyday life depends on various genetic and environmental factors [3]. Regarding diagnostic classification, there are categorical models (dependent vs. non-dependent) and dimensional models (expression of severity). The ICD-10 classification system is based on a categorical classification. The criteria refer firstly to harmful use and secondly to the dependence syndrome [4]. In the DSM-5 [5,6] the differentiation between harmful use/abuse (“substance abuse”) and dependence (“substance dependency”) is removed. The symptom criteria of both categories are defined under the term substance use disorder.

“Craving” is considered a new criterion. It is a semi-dimensional categorization system, as differentiation is made into different degrees of severity (mild severity = two to three symptoms, moderate severity = four to five symptoms, severe severity > six symptoms). The advantages and disadvantages of categorical and dimensional models are controversial. From a neuroscience perspective, disruption of reward processing is a central mechanism in addiction disorders (dopaminergic transmitter systems), assuming neurobiological correlates (vs. causality). The nature of the diagnostic assessment may have implications for therapeutic intervention methods and evaluation measures and is also relevant in terms of social insurance law.

Advantages and disadvantages of categorical vs. dimensional models

Matthias Kirschner, MD, of the Department of Psychiatry, Psychotherapy, and Psychosomatics at the Psychiatric University Hospital Zurich, cites a higher risk of stigmatization and a one-sided assessment of the course of therapy as potential problems of a categorical approach.

According to the categorical approach, it is obvious to judge a therapy as successful only if the result abstinence could be achieved. Dr. Kirschner points out that an improvement in a patient’s ability to function in everyday life can also be assessed as a therapeutic success, even if there is only a reduction in drinking quantity or the patient is receiving medication substitution. A study by Stern [7] also showed that dimensional models were a better predictor of change in substance use during treatment. From a neurobiological perspective, concepts should be elaborated that are based on pathophysiological data and not exclusively on descriptive ones. That is, rather than categorizing by disorder (e.g., schizophrenia, substance dependence disorders, bipolar disorders, etc.), define domains (e.g., executive function disorders, motivational behavior disorders, etc.). This is to promote translation of neurobiological research into clinical and treatment settings [8].

It has been empirically proven that various disorders are associated with impaired reward processing or with the corresponding neurobiological correlate [9]. Namely, individuals with depression, schizophrenia, or alcohol dependence showed altered dopaminergic reactivity to reward stimuli compared to a control group of healthy individuals [9]. However, there is a big gap between the findings of neurobiological research and the clinical-therapeutic implementation.

In summary, there are great efforts to transfer findings of neurobiological research into clinical practice, but it is enormously complex to develop practicable concepts [8].

Evidence-based treatment of alcohol dependence

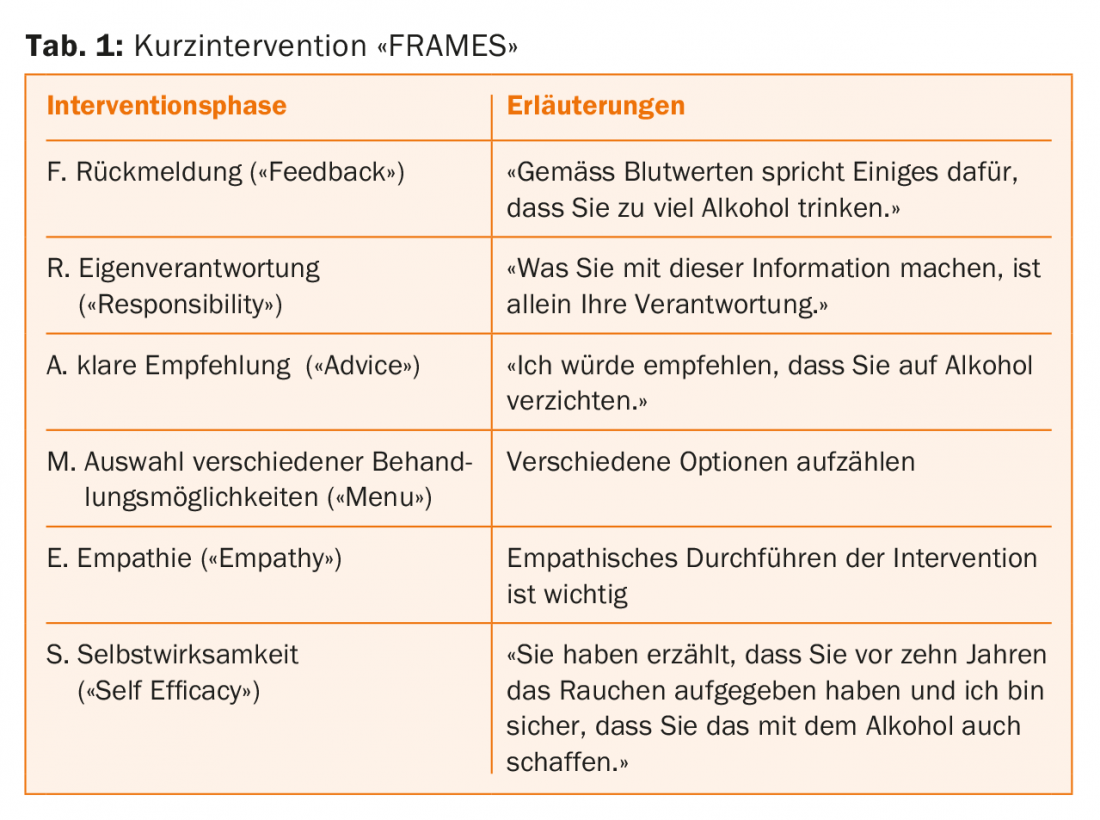

In his presentation, Prof. Dr. med. Gerhard Wiesbeck from the Center for Dependence Diseases of the University Psychiatric Clinics Basel addressed the evidence-based treatment of alcohol dependence and provided information on new findings in this context. The basis for evidence-based treatment is the German S3 guideline “Screening, diagnosis and treatment of alcohol-related disorders”, which is also used in Switzerland [10]. The screening test “AUDIT” (“Alcohol Use Disorder Identification Test”) is proposed as a diagnostic tool [11]. If a patient was found to exceed the cut-off value (men: >=8, women: >=5), brief intervention may be considered. The guideline recommends the brief intervention “FRAMES” (Tab. 1) [12,13].

The treatment regimen recommended by the guideline (extensive intervention) includes the following four treatment phases: 1. Motivation, 2. Withdrawal/detoxification, 3. weaning, 4. aftercare:

Phase 1: Motivation

Experience has shown that the motivation phase (i.e., getting the patient to accept therapy) is the biggest hurdle, according to Prof. Wiesbeck. The theoretical basis is the model of stages of change [14,15]. Convincing patients is done through a step-by-step approach adapted to the patient’s motivational stage:

Intentionlessness: The patient is not yet aware of the dependency problem. The treatment person should make the patient aware of problems and risks of his current behavior.

- Intention formation: The patient comes to terms with the dependency problem. The treatment person should respond to the patient’s ambivalence, work out reasons for change and strengthen self-confidence for changeability.

- Preparation phase: The patient plans initial measures of change, but not necessarily abstinence. The treatment person supports the patient in finding the best way to change the current behavior.

- Action phase: The patient decides to abstain and enter treatment. The treatment person supports the patient to implement appropriate steps of change.

- Maintenance: the treatment person supports the patient to develop and use appropriate strategies to prevent relapse.

- Relapse: the treatment person supports the patient to resume the process of change and not to get discouraged.

The Motivational Interviewing method by Miller and Rollwick [16] was developed for counseling people with addiction problems and is used to resolve ambivalent attitudes toward behavior change. An important component relates to accepting resistance and ambivalence as “normal.” This is a big difference from previous approaches. Motivation to change is not a prerequisite for therapy, but a goal of counseling.

Phase 2: Withdrawal/detoxification

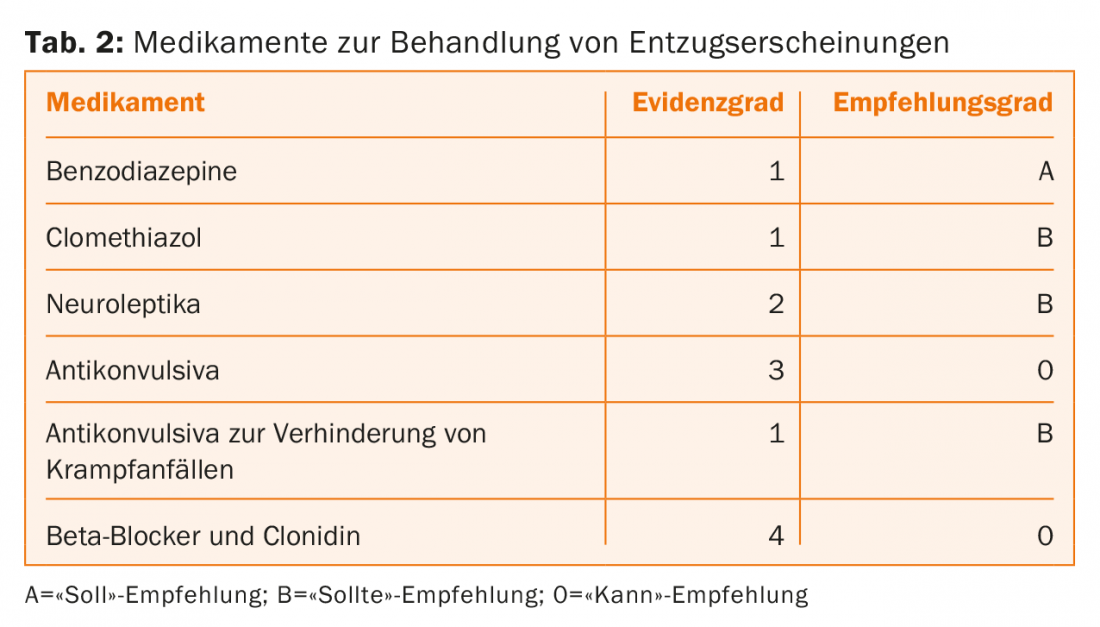

If it is possible to motivate the patient to undergo therapy, withdrawal/detoxification follows in a second phase. This includes cessation of substance intake, readjustment of all organ systems to a state of abstinence, and symptomatic and preventive drug treatment of withdrawal syndrome. The first question is whether this should be done in an outpatient or inpatient setting. Most patients prefer to receive treatment in an outpatient setting on their own accord. According to the guideline, outpatient treatment can be offered if no severe withdrawal symptoms or complications are expected, there is high adherence and a supportive social environment. According to the guideline, inpatient treatment should be offered if at least one of the following criteria is met: (expected) severe withdrawal symptoms, severe and multiple concomitant or secondary somatic or psychological diseases, suicidality, lack of social support, failure of outpatient detoxification. The next step is alcohol withdrawal. To assess the severity of alcohol withdrawal syndrome (“mild,” “moderate,” “severe”), the Alcohol Withdrawal Scale by Wetterling [17] can be used. This forms the basis for pharmacotherapy, which according to the guideline should be symptom-driven. There is a guideline recommendation for the following substances: benzodiazepines, clomethiazole, neuroleptics, anticonvulsants, anticonvulsants to prevent seizures, beta-blockers and clonidine (tab. 2) . If a mild to moderate alcohol withdrawal syndrome is present, benzodiazepines or clomethiazole or anticonvulsants should be used. If a severe alcohol withdrawal syndrome is present, benzodiazepines or clomethiazole should be used for treatment. If delirium is present, treatment should be with benzodiazepines or clomethiazole combined with neuroleptics (butyrophenones). Prof. Wiesbeck answers a frequently asked question about which benzodiazepine is most suitable as follows: The best benzodiazepine is the one with which the treatment team has the most experience. Experience shows that clomethiazole (Distraneurin®) is often used in Germany and Librium® in the USA. In Basel, however, oxazepam (e.g. Seresta®) is often used.

Phase 3: Weaning

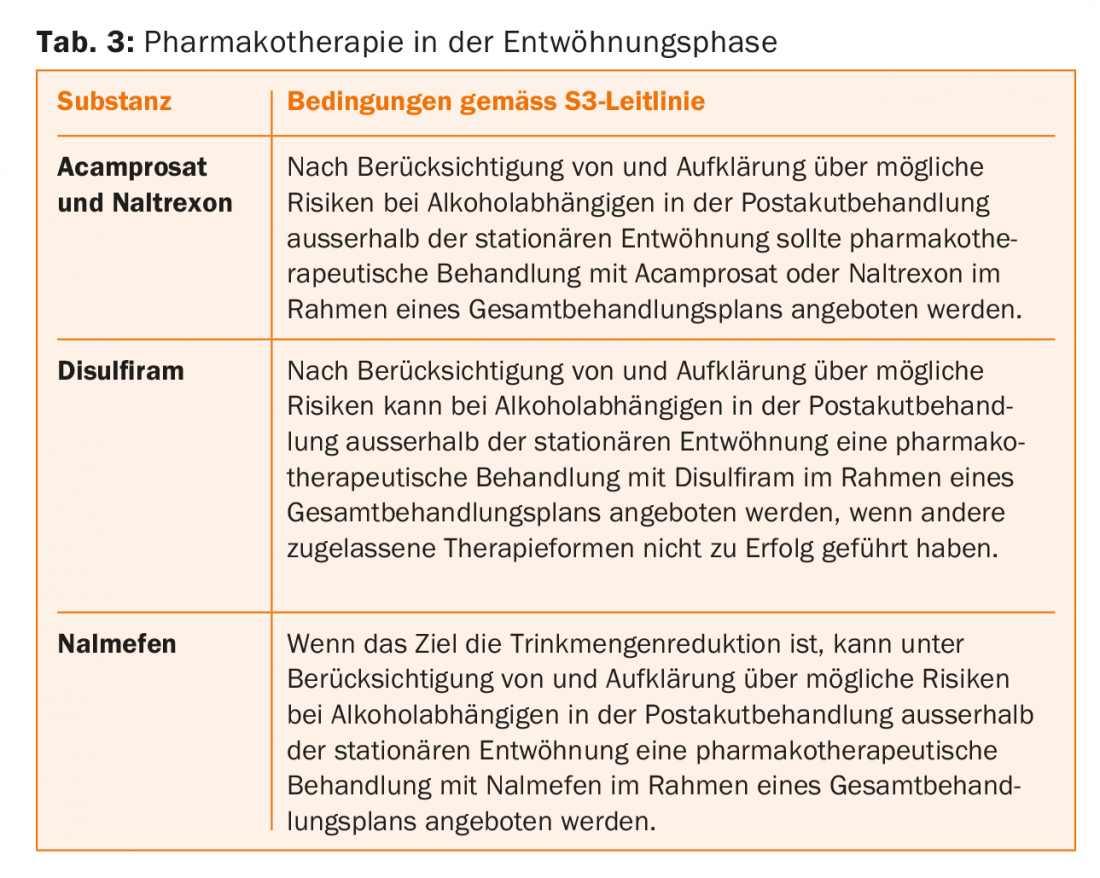

After the very somatically oriented detoxification, weaning begins, the actual addiction-specific psychotherapy. Studies show that after detoxification therapy alone, the risk of relapse is over 90% [18,19]. After implementation of inpatient cessation therapy, the relapse rate is still 64%, but it is considerably lower in comparison [20]. This should be communicated to the patient as motivation against premature discontinuation of treatment. For drug treatment of addiction, the guideline recommends the following substances: Acamprosate, naltrexone, disulfiram, nalmefene (Table 3).

Baclofen (e.g., Lioresal®) is a relatively new substance for the treatment of alcohol dependence syndrome [21,22]. It is a prescription medication that is approved for the market as a muscle relaxant. Empirical evidence of efficacy is currently mixed. There are two large randomized trials on this, but they come to different conclusions. Professor Wiesbeck is of the opinion that, based on the current findings, it is not yet possible to make a recommendation on the use of baclofen.

In addition to pharmacotherapy, the following psychotherapeutic interventions can be used in the phase of weaning according to the guideline: Motivational forms of intervention, cognitive behavioral therapy, contingency management, work with relatives, couples therapy, guided patient groups, neurocognitive training. As a criterion for deciding which of the forms of therapy to use, Professor Wiesbeck points out that a form of intervention should be chosen that is as well suited as possible to the patient and his or her symptoms.

Deep brain stimulation is a newer approach to treating addiction syndrome. In a study published in 2016, five cases of treatment-resistant alcohol dependence showed a significant decrease in alcohol craving after deep brain stimulation. However, controlled studies with higher case numbers are lacking to date [23].

Phase 4: Aftercare

On the one hand, Prof. Wiesbeck advises frequent short-term GP contacts in the initial phase; after stabilization, the intervals can be extended. On the other hand, aftercare also includes a support group. Already during the therapy stay, patients should be given opportunities to get to know different self-help groups and to locate the appropriate group.

Assessment of dependency disorders in the context of social insurance.

Dr. med. Claudine Aeschbach, Psychiatric Services for Dependence Diseases Baselland, explains the current social insurance law situation with regard to dependence diseases. Currently, substance dependence disorders are only recognized as a reason for disability by the IV if they are a consequence of a primary illness (e.g. depression, bipolar disorder, schizophrenia) or result in irreversible disabling health damage (e.g. cirrhosis of the liver, Korsakoff dementia). There is a great deal of tension between case law and medical knowledge. For example, substance dependence is not assessed as a disease by the user of the law, but this contradicts the KVG (Federal Health Insurance Act), where dependence is considered a disease. There are also discrepancies between the current legal situation and the medical facts and clinical experience regarding the relationship between work ability and substance dependence. Dr. Aeschbach points out that the legal assumption that withdrawal is reasonable and has a positive effect on functional and working capacity is not based on empirical evidence and often contradicts reality.

A study by the Research Network for Inpatient Addiction Treatment [24] showed that nearly half (46%) of all people who were in inpatient addiction treatment in 2016 were dependent on social assistance for living expenses in the six months prior to treatment, and 13% were dependent on a pension. Only 15% were able to cover their living expenses with their own income. Whereas more than half of the study population (58.3%) had been in inpatient treatment at an earlier time and almost 90% had already undergone withdrawal. That the low labor force participation rate is rather not due to a lack of educational qualifications is shown by the following statistics from the aforementioned study: 75.9% have completed compulsory schooling and 46.1% have completed basic vocational education or vocational training. When evaluating the motivation for therapy, it is noticeable that about half of the patients state an addiction-free life as a therapy goal, but for only 16.5% vocational training/integration is a motivation for therapy. According to Dr. Aeschbach, this is not only a problem of the patients, but the topic of professional integration has so far been neglected by the inpatient facilities and sometimes not even a registration with the disability insurance is made, whereby the hurdles for the recognition of an addiction problem as a reason for disability are high, as already mentioned. Efforts are currently underway to improve the social security situation of persons with substance dependence disorders. According to a study published in 2016 [25], so-called “standard criteria” should be applied for diagnostic assessment. This means that the effective performance and functional ability of individuals is assessed. This is the basis of the scheme for the assessment of somatoform disorders approved by the Federal Supreme Court [25]. Whether this will also be applicable to the assessment of addiction disorders in the future is currently unclear, Dr. Aeschbach said.

Links to the videos:

- Categorical vs. dimensional models of addiction

- Update Evidence-Based Treatment of Alcohol Dependence

- The assessment of dependency disorders in the context of social insurance.

Literature:

- Lim S, et al: A comparative risk assessment of burden of disease and injury attributable to 67 risk factors and risk factor clusters in 21 regions, 1990-2010: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2010. The Lancet 2012; 308 (9859): 2224-2260.

- Swiss Federal Statistical Office: Health Determinants 2012, www.bfs.admin.ch/bfs/de/home/statistiken/gesundheit/determinanten/tabak.html

- Edwards G, Gross MM: Alcohol dependence: provisional description of a clinical syndrome. Br Med J 1976; 1(6017): 1058-1061.

- ICD-10-WHO-2016 Classification. Mental and behavioral disorders caused by psychotropic substances, www.dimdi.de/static/de/klassi/icd-10-who/kodesuche/onlinefassungen/htmlamtl2016/block-f10-f19.htm

- DSM-5-APA Systematics, www.psychiatry.org/psychiatrists/practice/dsm/dsm-5/

- American Psychiatric Association. Personality disorders. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders. 5th ed. Arlington, VA: American Psychiatric Publishing. 2013; 645-685.

- Stern TA, Fava M, Wilens TE, Rosenbaum JF (eds): Massachusetts General Hospital Comprehensive Clinical Psychiatry. Chapter 26. 2nd Edition. Philadelphia: Elsevier 2016 (pp. 272).

- Kwako LE, et al: Addictions Neuroclinical Assessment: A Neuroscience-Based Framework for Addictive Disorders. Biol Psychiatry 2016; 80(3): 179-189.

- Heinz A, Batra A, Scherbaum N, Gouzoulis-Mayfrank E: Neurobiology of addiction. Kohlhammer 2012.

- WMF Online: S3 guideline “Screening, diagnosis and treatment of alcohol-related disorders”. AWMF Register No. 076-001 As of Feb. 28, 2016, www.awmf.org/uploads/tx_szleitlinien/076-001l_S3-Leitlinie_Alkohol_2016-02.pdf

- Babor T, Higgins-Biddle J, Saunders J, Monteiro M: AUDIT. The Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test. Guidelines for Use in Primary Care. 2nd Edition. World Health Organization WHO 2001, Geneva, http://whqlibdoc.who.int/hq/2001/WHO_MSD_MSB_01.6a.pdf

- Bien TH, Miller WR, Tonigan, JS: Brief interventions for alcohol problems: A review. Addiction 1993; 88(3): 315-336.

- Miller WR, Sanchez VC: Motivating young adults for treatment and lifestyle change. In: Howard G, Nathan PE (Eds.): Alcohol Use and Misuse by Young Adults. University of Notre Dame Press 1994.

- Prochaska JO, Velicer WF: The transtheoretical model of health behavior change. Am J Health Promot 1997; 12: 38-48.

- Prochaska JO, DiClemente CC: Transtheoretical therapy: toward a more integrative model of change. Psychother Theory Res Pract 1982; 19: 276-288.

- Miller WR, Rollnick S: Motivational interviewing: Preparing people to change addictive behavior. New York: Guilford Press 1991.

- Wetterling T, et al: A new rating scale for the assessment of the alcohol-withdrawal syndrome (AWS scale). Alcohol Alcohol 1997; 32(6): 753-760.

- Vaillant GE: What can we learn from long-term studies of relapse and relapse prevention in drug and alcohol abusers? Why does relapse occur? In Watzl H, Cohen R (Eds.): Relapse and relapse prevention. Springer 1989 (pp. 37-39).

- National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism: Relapse and Craving. Alcohol Alert 1989, https://pubs.niaaa.nih.gov/publications/aa06.htm

- Bottlender M, Soyka M: Efficacy of an intensive outpatient rehabilitation program in alcoholism: predictors of outcome 6 months after treatment. Eur Addict Res 2005; 11(3): 132-137.

- Müller CA, et al: High-dose baclofen for the treatment of alcohol dependence (BACLAD study): a randomized, placebo-controlled trial. Eur Neuropsychopharmacol 2015; 25(8): 1167-1177.

- Reynaud M, et al: A Randomized, Placebo-Controlled Study of High-Dose Baclofen in Alcohol-Dependent Patients – The ALPADIR Study. Alcohol Alcohol 2017; 52(4): 439-446.

- Müller UJ, et al: Nucleus Accumbens Deep Brain Stimulation for Alcohol Addiction – Safety and Clinical Long-term Results of a Pilot Trial. Pharmacopsychiatry 2016; 49(4): 170-173.

- Schaaf S: The research network inpatient addiction therapy act-info-FOS in 2016 – Activity report and annual statistics 2017. Zurich: ISGF.

- Liebrenz M, et al: The disease of addiction or dependency disorders – possibilities of the expert opinion according to BGE 141 V 281 (= 9C_492/2014). Schweizerische Zeitschrift für Sozialversicherung und berufliche Vorsorge 2016: 12-44.

InFo NEUROLOGY & PSYCHIATRY 2018; 16(3): 33-39.