Anemia is a risk factor for maternal and fetal morbidity and mortality. Mild iron deficiency anemia and iron deficiency without anemia can be treated perorally during pregnancy. Intravenously, Ferinject® is used as standard.

Anemia is the most common disease in pregnancy and puerperium. The incidence of anemia in early pregnancy in Switzerland is approximately 18.5% [1]. Up to 6.2% have iron deficiency anemia and 12.3% of women have anemia of other causes [1]. Despite the good nutritional status in Switzerland, up to 32% of all pregnant women are iron deficient due to reduced storage iron before pregnancy and limited iron absorption. Hemoglobinopathies are another important cause of anemia. Migration in Europe has led to a significant increase in hemoglobinopathies, thalassemias as well as infectious anemias in Switzerland.

Definition of anemia in pregnancy and postpartum

According to the World Health Organization (WHO), “anemia in pregnancy” is defined as hemoglobin (Hb) below 110 g/l throughout pregnancy. The Centers for Disease Control (CDC) defines “anemia in pregnancy” as Hb below 110 g/l in the first and third trimesters and below 105 g/l in the second trimester [2]. The different limits are explained by the increased hemodilution in the second trimester. A distinction is made between mild (Hb 100-110 g/l), moderate (Hb 80-100 g/l) and severe (Hb <80 g/l) pregnancy anemia [2]. According to WHO, one speaks of “iron deficiency without anemia” when the ferritin value is below 15 μg/l and the hemoglobin value is within the norm. “Postpartum anemia” is defined as Hb <110 g/l in the first week after birth and Hb <120 g/l from the second week after birth.

Diagnostics and differential diagnosis

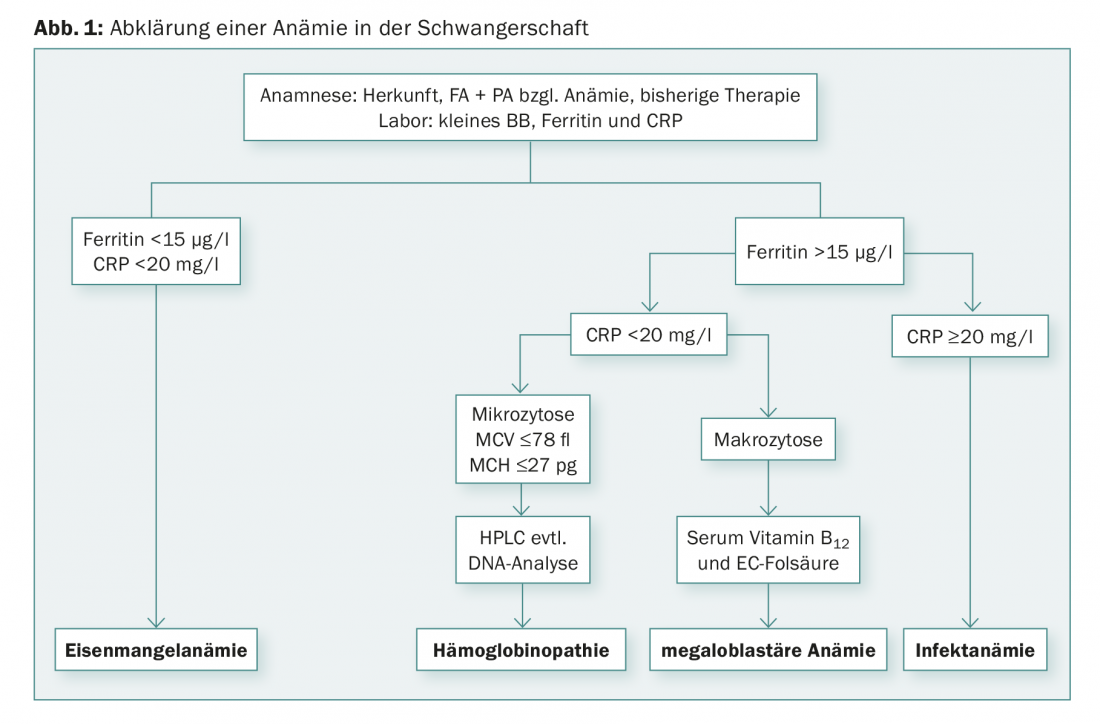

The first examination is the so-called small blood count. Classically, the classification of anemias is based on mean corpuscular volume (MCV). We speak differentially of microcytic (MCV decreased), macrocytic (MCV increased), and normocytic anemias. For the differential diagnosis of anemia, a determination of CRP, ferritin, folic acid and vitamin B12 should be performed (Fig. 1) . The current “gold standard” for detecting iron deficiency states is the determination of ferritin levels in plasma, which correlates well with iron stores. A ferritin value <15 µg/l is indicative of iron deficiency, regardless of the hemoglobin value [3,4]. Screening by ferritin determination is recommended in the first trimester. If the ferritin values are in the normal range, an iron deficiency can be practically ruled out, unless an infection is suspected at the same time. In this case, ferritin levels may be falsely normal because apoferritin, like C-reactive protein, is an acute-phase protein and increases during infections as well as inflammatory reactions (e.g., postoperative). In clinical situations with elevated CRP, iron deficiency can be detected using the (elevated) soluble transferrin receptor. Significant macrocytosis (MCV of >100 fl) indicates the presence of megaloblastic anemia. Most megaloblastic anemias in pregnancy are due to folic acid deficiency, whereas vitamin B12 deficiency anemias are less common.

If there is marked microcytosis in the blood count, i.e., an MCV <75 fl, an MCH <25 pg, or a percentage of microcytes of >15%, with normal ferritin and normal CRP, Hb chromatography or Hb electrophoresis should be performed to exclude β-thalassemia and hemoglobinopathy [5,6]. The diagnosis of β-thalassemia is made by determining HbA2, the percentage of which is elevated compensatory for missing β-chains (>3.5%). Likewise, the HbF fraction may be elevated (not mandatory). However, the HbA2 percentage may be lower in the presence of concomitant iron deficiency. Patients with α-thalassemia have normal Hb chromatography; the diagnosis is made by genetic testing after exclusion of other causes of microcytic anemia. If thalassemia or hemoglobinopathy is known, the partner must also be evaluated to rule out risk for infantile homozygous thalassemia and hemoglobinopathy. If both partners are heterozygous carriers for thalassemia or hemoglobinopathy, prenatal diagnosis in terms of amniocentesis or chorionic villus sampling is indicated.

Clinical significance

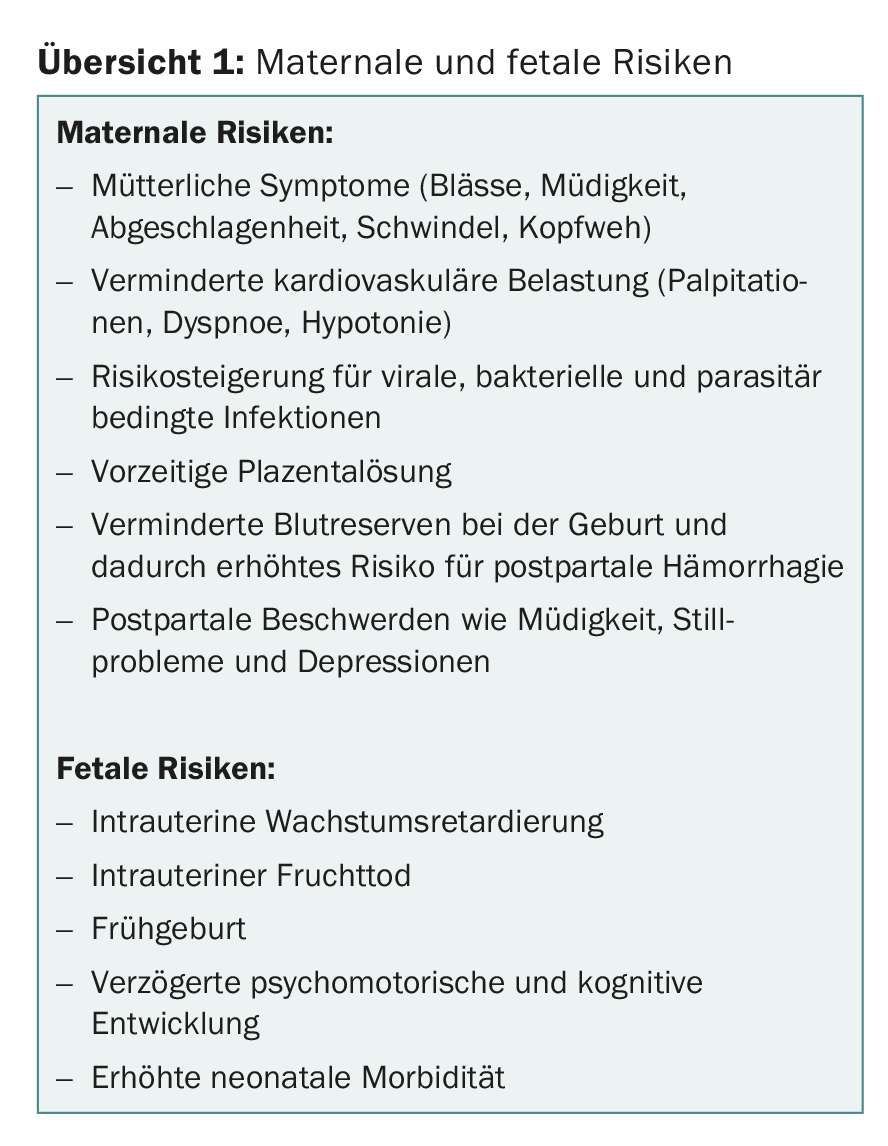

Maternal and fetal risks in the setting of iron deficiency anemia should be related not only to the degree of anemia and gestational age but also to the degree of depletion of iron stores [7]. Possible consequences of iron deficiency anemia include maternal symptoms (pallor, fatigue, lassitude, dizziness, headache), decreased cardiovascular stress (palpitations, dyspnea, hypotension), increased risk of viral, bacterial and parasitic infections, premature placental abruption, reduced blood reserves at birth and thus increased risk of postpartum hemorrhage, and increased risk of postpartum symptoms such as fatigue, breastfeeding problems, and depression. (Overview 1). The fetus is at increased risk for intrauterine growth restriction, intrauterine fetal death, preterm birth, and, in general, neonatal morbidity and delayed psychomotor and cognitive development.

Therapy of anemia in pregnancy

Therapy depends on the cause of anemia. In the case of iron deficiency or mild iron deficiency anemia, oral iron supplements should remain first-line agents; except in patients who require treatment with erythropoietin or have inflammatory bowel disease [8]. In therapy, mainly oral iron II and iron III preparations are used. These differ in tolerability, which may vary from patient to patient. Good information about possible side effects and precise dosage recommendations can be helpful in improving compliance, which is usually poor. Oral iron treatment is inexpensive and effective if followed strictly and for a sufficiently long period of time. However, a long treatment period due to the low absorption rate, as well as the occurrence of side effects, affect the disciplined adherence to such therapy.

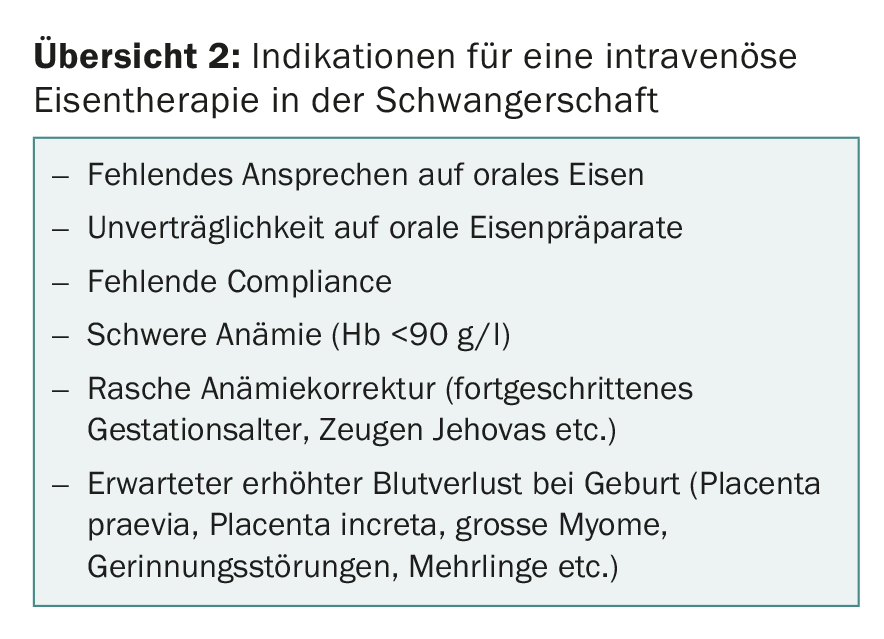

If oral iron therapy is unsuccessful or not tolerated by the patient, switch to intravenous iron treatment. Other indications for intravenous iron therapy in pregnancy include: poor compliance, severe anemia, the need for high peripartum hemoglobin levels or rapid hemoglobin increase (advanced gestational age, expectation of peripartum hemorrhage, e.g., placenta praevia, uterine distension, large uterine fibroma, coagulopathy, and Jehovah’s Witness) (review 2).

Since the various studies have shown that avoidance of perioperative and postoperative blood transfusion improves morbidity and mortality, high-dose intravenous iron therapy should always be considered in planned sectiones with expected high blood loss (placenta praevia, placenta increta, large fibroids, etc.) toward the end of pregnancy.

Intravenous iron administration is contraindicated in the first trimester. Today, the standard iron carboxymaltose (Ferinject®) is used for intravenous iron therapy in pregnancy and postpartum [9,10]. Data show that intravenous administration of ferric carboxymaltose (Ferinject®) in the second and third trimesters of pregnancy is as safe as ferrous sucrose (Venofer®) in terms of maternal side effects and is better tolerated at higher doses. Severe intolerance reactions following ferric carboxymaltose were not described in any study. Dosage is determined depending on hemoglobin level and body weight. Within two weeks the hemoglobin increase should be 10-20 g/l, if necessary a second infusion can be given. The therapeutic goal is a hemoglobin level of at least 110 g/l. In special cases, iron therapy can be combined with recombinant human erythropoietin (rhEPO). It must be noted that this is an “off-label-use” drug and the cost coverage by the health insurance must be clarified in advance.

Therapy of postpartum anemia

The nadir of Hb value postpartum is reached 48 hours after primary plasma volume distribution. Basically, the therapy depends on the severity of the anemia and the condition of the woman in labor. In mild anemia (Hb 95-110 g/l), peroral iron therapy of approximately 80-200 mg iron per day is recommended. In moderate (Hb 85-95 g/l), severe anemia (Hb <85 g/l) and intolerance to peroral iron therapy, intravenous iron treatment is recommended as the first choice. At Hb <80 g/l, administration of rhEPO in addition to parenteral iron carboxymaltose may be considered at best. However, the evidence of additional efficacy of rhEPO in combination with intravenous iron therapy compared with intravenous iron therapy alone is very limited. If Hb <60 g/l, foreign blood transfusion should be performed depending on clinical symptoms.

Take-Home Messages

- Iron deficiency is the most common cause of anemia worldwide. Screening is recommended in the first trimester by ferritin determination.

- Another important cause of anemia is genetic hemoglobinopathies. The workup of β-thalassemia and hemoglobinopathy is performed with hemoglobin chromatography or hemoglobin electrophoresis.

- Anemia, depending on its severity, is a significant risk factor in terms of maternal and fetal morbidity and mortality.

- Primarily, mild iron deficiency anemia and iron deficiency without anemia in pregnancy should be treated with peroral iron therapy.

- For intravenous iron therapy in pregnancy and the puerperium, the standard iron carboxymaltose (Ferinject®) is used, which is very well tolerated.

Literature:

- Bencaiova G, Burkhardt T, Breymann C: Anemia – prevalence and risk factors in pregnancy. Eur J Intern Med 2012 Sep; 23(6): 529-533.

- Centers for Disease Control (CDC): CDC criteria for anemia in children and childbearing-aged women. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 1989; 38(22): 400-404.

- Breyman C: Iron deficiency anemia in pregnancy. Expert Rev Obstet Gyn 2013; 8(6): 587-596.

- Milman N: Iron in Pregnancy – How do we secure an appropriate iron status in the mother and child? Ann Nutr Metab 2011; 59: 50-54.

- Merlo CM, Wuillemin WA: Prevalence and causes of anemia in an urban family practice. Praxis 2008; 97(5): 713-718.

- Lopez A, et al: Iron deficiency anemia. Lancet 2016; 387(10021): 907-916.

- Breymann C: Anemia. In: Schneider H, Husslein P, Schneider KTM (eds.): Obstetrics. Springer Verlag 1999; 371-385.

- Swiss Medical Board: Oral or parenteral treatment of iron deficiency. Report dated October 24, 2014.

- Breymann C, et al: SGGG Expert Letter No 48. Diagnosis and therapy of iron deficiency anemia in pregnancy and postpartum. Updated version of 11.01.2017 (replaces Expert Letter No 22).

- Breymann C, et al; FER-ASAP investigators: ferric carboxymaltose vs. oral iron in the treatment of pregnant women with iron deficiency anemia: an international, open-label, randomized controlled trial (FER-ASAP). J Perinat Med 2017 May 24; 45(4): 443-453.

InFo ONCOLOGY & HEMATOLOGY 2018; 6(2): 28-32.