Substance use disorders (SGS) are prevalent throughout the world. According to the World Health Organization, the prevalence is around 4-5% worldwide. In addition to lowering the entry threshold for initial treatment, successful treatment also requires an individually tailored, integrated and modular therapy that includes psychiatric comorbidities in addition to substance-specific treatment.

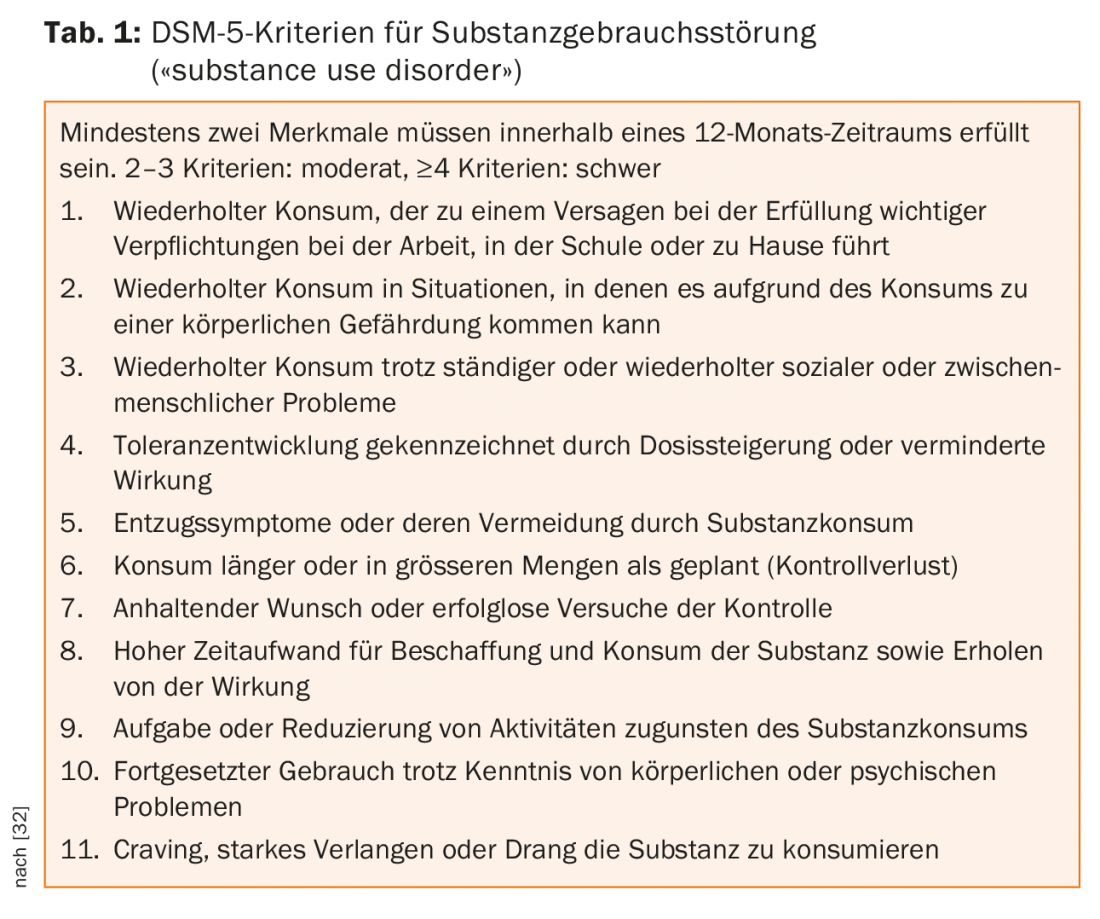

Substance use disorders (SGS) (Table 1) are common throughout the world [1]. According to the World Health Organization, the prevalence of SGS is around 4-5% worldwide [2]. According to the Federal Office of Public Health, around 250,000 people in Switzerland alone are dependent on alcohol [3]. Direct and indirect consequences of consumption result in high socioeconomic costs. Alcohol abuse alone causes annual costs of around 4.2 billion Swiss francs in Switzerland [4]. The core feature of SGS is the persistent often compulsive use of substances despite negative consequences [5]. SGS are often characterized by a chronic course with repeated relapses. Regarding the etiology, a complex interaction between bio-psycho-social factors and the properties of the substance is postulated [6].

Supply deficit of SGS

Although people with SGS are frequent users of the health care system, there is a clear deficit in care, in the form of affected people not receiving treatment at all or receiving it very late. For example, the coverage gap for alcohol use disorders (AGS) is 76% on average [7]. In an American study, it was shown that despite the insight regarding the need for treatment, almost half of the persons with AGS were not prepared to stop alcohol consumption, but aimed to reduce it [8].

In the English and meanwhile also in the German therapy guideline [9], a reduction of the drinking quantity is accordingly suggested as a therapy goal also in the sense of a “harm reduction”. Despite the high burden of disease caused by SGS [10], they are stigmatized in society and their definition as a disease is often questioned [11]. Therefore, early detection, motivational work, and stigma reduction play an important role in lowering the entry threshold for treatment. In addition, dovetailing various services is central to ensuring the most effective and sustainable treatment possible.

Psychiatric comorbidity in SGS.

Despite growing evidence-based treatment approaches for SGS, 50-60% of sufferers relapse within one year of receiving treatment [12]. Moreover, clinical practice shows that people with SGS often present with complex clinical pictures and suffer from additional mental disorders (dual diagnosis patients). The prevalence of psychiatric comorbidity ranges from 30-45% for patients with AGS and 45-72% for those with SGS of illicit substances [13,14]. An integrative, multiprofessional treatment approach that addresses the additional mental disorders in addition to SGS has been shown to be superior to non-integrated treatments [15]. Not all dual diagnosis patients benefit from the same interventions in this regard. Therefore, the treatment offer should be tailored to the individual patient [16,17].

As recent research illustrates, patients with SGS are more likely to experience traumatic events, and these traumas are also more severe than in the normal population [18]. The prevalence of post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) in patients with SGS ranges from 25-51% [19-21]. Patients with trauma and SGS are more likely to relapse and drop out of treatment and are often excluded from trauma-specific treatments due to SGS [22,23]. However, inclusion of trauma sequelae disorder in the treatment of SGS should be sought. For this reason, integrated therapeutic treatment services are needed to provide patients with flexible, longer-term successful strategies.

Evidence-based treatment approaches for SGS and psychiatric comorbidities.

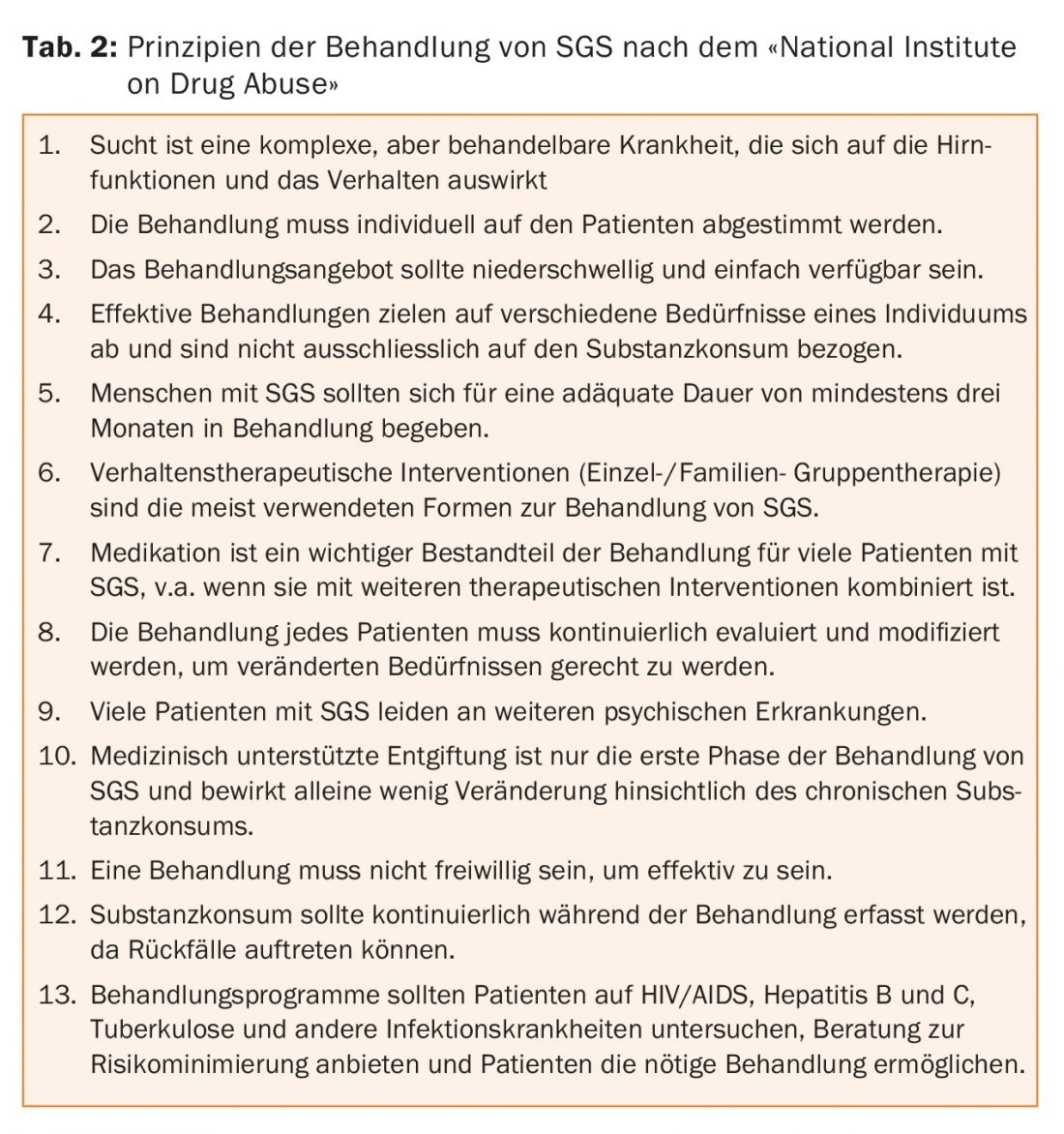

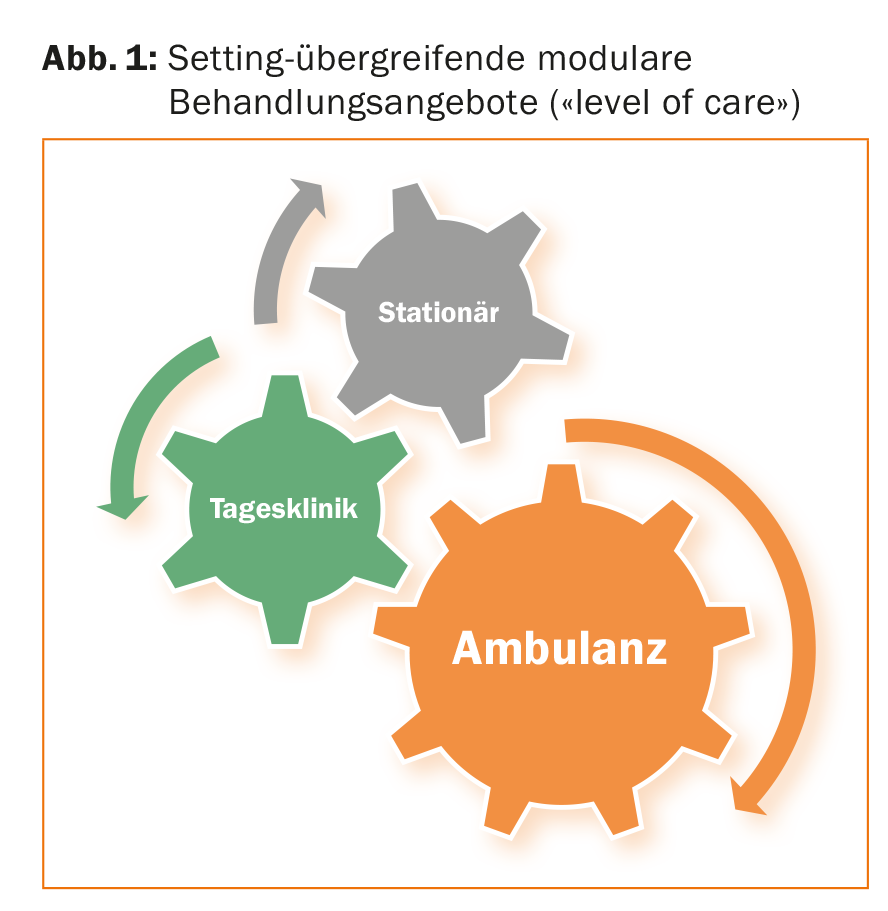

The National Institute on Drug Abuse (NIDA) has postulated thirteen key aspects for effective treatment of SGS (Table 2) [24]. It is emphasized that the treatment of SGS should be individualized to each patient and his or her comorbidities, if any. An example of an integrated modular treatment program is outlined below, showing how the various treatment units are interlinked (Fig. 1).

Multimodal therapy for SGS and dual diagnoses.

Ideally, there is an individually combinable, modular treatment offer for both inpatient and day-care treatment. In addition to somatomedical and pharmacological treatment, psychotherapeutic group therapy plays an important role. A combination of diagnosis-specific group services, skills-based groups, art and occupational therapy, and activation and movement groups have proven to be very valuable in practice.

An inpatient treatment setting may be necessary to gain distance from substance use behaviors away from familiar surroundings and to provide withdrawal treatment and/or crisis intervention. In these situations, treatment under outpatient or day-care conditions is usually not possible. Inpatient treatment, which varies according to the individual, may also include further diagnostic clarification (of additional mental and somatic disorders), motivational approaches, and intensified psychotherapeutic treatment of substance-specific and other mental disorders in both individual and group settings.

Subsequent day-care treatment in a day clinic corresponds to an intermediate level of care and allows consolidation of the abstinence or substance reduction achieved in the inpatient setting, as well as more in-depth therapy of psychological comorbidities. For outpatients, the intention may also be to avoid inpatient interventions by offering more intensive therapy. Important overarching goals here, as in all settings, are the regaining of health and social and occupational integration (recovery). Compared to outpatient treatment, the day-care setting offers a more intensive implementation of therapeutic goals, motivates through the group setting and serves to expand the social network. In addition, there is a closer link between the therapy content and everyday events.

Selected psychotherapeutic group therapies.

Relapse prevention should occur early in the treatment of people with SGS and, in addition to relapse management, should aim to make individuals experts in their disease. Relapse prevention looks to reduce the risk of relapse by improving self-control function. High-risk situations should be identified and coping strategies taught. Strategies for dealing with cravings for substances (craving) are also to be learned. Central to this is damage control after relapses [25].

Mindfulness training allows better control of impulsive emotional behavior and shows a positive impact on cognitive abilities in people with SGS. The goal is to help patients move from a mode of passive-automated responding to active, self-directed action as a prerequisite for using further relapse management strategies [26,27].

Interactive skills training can help improve profound disorders of emotion regulation and self-esteem [28]. Training is designed to make patients aware of skills they already have so they can apply them in crisis situations. In addition, new skills are to be learned, trained and automated.

Seeking Safety is an integrative treatment program for individuals with SGS who suffer from the effects of traumatic experiences [29]. The stabilizing and resource-based approach consists of cognitive, behavioral, and interpersonal interventions. Patients learn strategies for dealing with symptoms of trauma (“flashbacks,” nightmares, negative feelings), practice living without consumption, learn to take good care of themselves and gain safety, find reliable people, free themselves from domestic violence, and prevent self-harming behaviors.

Schema therapy was designed for patients with personality disorders and complex trauma sequelae [30]. The basic assumption is that when children’s needs are not met/violated, maladaptive schemas emerge that lead to dysfunctional coping strategies. In addition to cognitive-behavioral and emotion-activating interventions, “limited reassurance” and empathic confrontation play an important role. Patients should learn to change painful feelings and dysfunctional behavior patterns in the sense of post-maturation.

The Cognitive Behavioral Analysis System of Psychotherapy (CBASP) [31] was developed for patients with chronic depression. The goals are the recognition of the consequences of one’s own behavior, the acquisition of authentic empathy, the learning of social problem-solving skills and coping strategies, and an interpersonal healing process with regard to earlier traumas. This is accomplished through situation and discriminant analysis, as well as “Disciplined Personal Involvement” by the therapist.

Conclusion for practice

To provide optimal care for people with SGS, lowering the entry threshold for initial treatments is key. Successful treatment requires an individually tailored, integrated and modular therapy that includes psychiatric comorbidities in addition to substance-specific treatment. In particular, trauma-specific therapy plays an important role in patients with SGS. To address the complexity of SGS and dual diagnoses and promote sustainability, close integration and continuity across different levels of care (“level of care”) is central. Ideally, therefore, there is a close link between inpatient, day-care and outpatient therapy services. In addition to continuous monitoring and support of the patients, this enables a cross-setting consolidation of the therapy contents.

Take-Home Messages

- To provide optimal care for people with substance use disorders, lowering the entry threshold for initial treatment is key.

- Successful treatment requires therapy that is individually tailored to the patient, integrated and modular,

- which includes psychiatric comorbidities in addition to substance-specific treatment.

- Trauma-specific therapy in patients with SGS has an important role to play.

- Close linkage between inpatient, day-care and outpatient therapy services enables cross-setting consolidation of therapy content.

Literature:

- UNODC. World Drug Report 2012: (United Nations publication, Sales No. E.12.XI.1).

- Wittchen HU, Jacobi F, et al: The size and burden of mental disorders and other disorders of the brain in Europe 2010. Eur Neuropsychopharmacol 2011; 21(9): 655-679.

- Kuendig H (2010): Estimation du nombre de personnes alcoolo- dépendantes dans la population helvétique (Rapport de recherche, 56). Lausanne: Addiction Info Suisse.

- Fischer B, Telser H, et al. (2014): Alcohol-related costs in Switzerland. Final report commissioned by the Federal Office of Public Health Contract No. 12.00466. Olten: Polynomics.

- Volkow ND, Koob GF, McLellan AT: Neurobiologic Advances from the Brain Disease Model of Addiction. N Engl J Med 2016; 374 (4): 363-371.

- Volkow ND, Morales M: The Brain on Drugs: From Reward to Addiction. Cell 2015; 162 (4): 712-725.

- Kohn R et al: The treatment gap in mental health care. Bull World Health Organ 2004; 82 (11): 858-66.

- Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (SAMHSA), Results from the 2012 National Survey on Drug Use and Health: Summary of National Findings, NSDUH Series H-46, HHS Publication No. (SMA) 13-4795. Rockville, MD: SAMHSA – Fed. Government Agency, 2013.

- NICE. Alcohol-use disorders: diagnosis, assessment and management of harmful drinking and alcohol dependence (CG 115). National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence 2011.

- Lim SS, Vos T, et al: A comparative risk assessment of burden of disease and injury attributable to 67 risk factors and risk factor clusters in 21 regions, 1990-2010: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2010. Lancet 2012; 380 (9859): 2224-2260.

- Yang LH, Wong LY, et al: Stigma and substance use disorders: an international phenomenon. Curr Opin Psychiatry 2017; 30 (5): 378-388.

- Sinha R: Modeling relapse situations in the human laboratory. Curr Top Behav Neurosci 2013; 13: 379-402.

- Regier DA, Farmer ME et al: Comorbidity of mental disorders with alcohol and other drug abuse. Results from the Epidemiologic Catchment Area (ECA). Study. JAMA 1990; 264 (19): 2511-2518.

- Farrell M et al: Substance misuse and psychiatric comorbidity. Int Rev Psychiatry 2003; 15 (1-2): 43-49.

- Worley MJ et al: Service utilization during and after outpatient treatment for comorbid substance use disorder and depression. J Subst Abuse 2010; 39 (2): 124-131.

- Brunette MF, Mueser KT: Psychosocial interventions for the long-term management of patients with severe mental illness and co-occurring substance use disorder. J Clin Psychiatry 2006; 67 Suppl 7:10-17.

- Moggi F, Donati R: Mental disorders and addiction: Dual diagnoses. Göttingen: Hogrefe, 2004.

- Khoury L, Tang YL, et al: Substance use, childhood traumatic experience, and Posttraumatic Stress Disorder in an urban civilian population. Depressed Anxiety 2010; 27 (12): 1077-1086.

- Reynolds M, Mezey G, et al: Co-morbid post-traumatic stress disorder in a substance misusing clinical population. Drug Alcohol Depend 2005; 77 (3): 251-258.

- Ouimette P, Read J, Brown PJ: Consistency of retrospective reports of DSM-IV criterion A traumatic stressors among substance use disorder patients. J Trauma Stress 2005; 18 (1): 43-51.

- Kok T, de Haan HA et al: Screening of current post-traumatic stress disorder in patients with substance use disorder using the Depression, Anxiety and Stress Scale (DASS-21): a reliable and convenient measure. Eur Addict Res 2015; 21(2): 71-77.

- Westermeyer J, Wahmanholm K, Thuras P: Effects of childhood physical abuse on course and severity of substance abuse. Am J Addict 2001; 10 (2): 101-110.

- Hien DA, Nunes E, et al: Posttraumatic stress disorder and short-term outcome in early methadone treatment. J Subst Abuse Treat 2000; 19 (1): 31-37.

- National Institute on Drug Abuse. Principles of drug addiction treatment. (Third Edition) Revised Dec 2012. www.drugabuse.gov/publications/principles-drug-addiction-treatment-research-based-guide-third-edition/principles-effective-treatment.

- Curry SJ, Marlatt GA, et al: A comparison of alternative theoretical approaches to smoking cessation and relapse. Health Psychol 1988; 7 (6): 545-556.

- Hosseinzadeh Asl N, Barahmand U: Effectiveness of mindfulness-based cognitive therapy for co-morbid depression in drug-dependent males. Arch Psychiatr Nurs 2014; 28 (5): 314-318.

- Garland EL, Roberts-Lewis A, et al: Mindfulness-Oriented Recovery Enhancement versus CBT for co-occurring substance dependence, traumatic stress, and psychiatric disorders: Proximal outcomes from a pragmatic randomized trial. Behav Res Ther 2016; 77: 7-16.

- Dimeff LA, Linehan MM: Dialectical behavior therapy for substance abusers. Addict Sci Clin Pract 2008; 4 (2):39-47.

- Najavits LM, Weiss RD, et al: “Seeking safety”: outcome of a new cognitive-behavioral psychotherapy for women with posttraumatic stress disorder and substance dependence. J Trauma Stress 1998; 11 (3): 437-456.

- Young JE, Klosko JS, Weishaar ME: Schema therapy. A practical handbook. Junfermann Verlag, 2008.

- McCullough JP: Treatment for Chronic Depression: Cognitive Behavioral Analysis System of Psychotherapy (CBASP). Guilford Press, 2000.

- Rumpf H, Kiefer F: DSM-5: Eliminating the distinction between dependence and abuse and opening it to behavioral addictions. Addiction 2011; 57 (1):45-48.

InFo NEUROLOGY & PSYCHIATRY 2017; 15(6): 3-8.