People who actively or passively use tobacco are more likely to suffer from cardiovascular disease. Tobacco use promotes atherothrombosis and its consequences. Tobacco cessation leads to cardiovascular risk reduction and improved quality of life. Nicotine-containing products and medications have been shown to be effective in smoking cessation. With regard to e-cigarettes, scientific studies on quality, short-/long-term safety, or suitability as a weaning agent are lacking to date. In addition, e-cigarettes should be regulated like other tobacco products (production, declaration of ingredients, advertising and sale). Until proven safe, they should be prohibited in enclosed public spaces, just like traditional cigarettes.

Active and passive smoking are the most important cardiovascular risk factors [1–3]. A 50-year follow-up of a study of British physicians showed that smokers lose approximately twelve (for men) and eleven (for women) years of life compared with nonsmokers [1]. It is never too late to quit smoking: People who quit smoking between the ages of 25-34 have about the same life expectancy as non-smokers. Those who stop smoking at age 55-64 lose “only” seven years of life, not twelve [1].

In Switzerland, more than 9000 people die each year from the consequences of tobacco consumption. That’s more than 25 premature deaths every day. A quarter of these affect people before the age of 65. Overall, 41% each of these tobacco-related deaths are caused by cancer and cardiovascular disease (according to the Federal Statistical Office).

The causal relationship between smoking and cardiovascular disease is well documented; compared to nonsmokers, smokers have at least a 1.5-3-fold increased risk. The risk is higher in younger compared to older individuals, and even the consumption of one to four cigarettes daily has been shown to bring increased cardiovascular risk. This increases progressively with the number of cigarettes smoked and years of tobacco use [4]. In patients with acute coronary syndrome [5] and those with complex coronary artery disease treated with PCA/stenting or bypass [6], tobacco use is associated with poor prognosis. When smoking low-tar and low-nicotine cigarettes, the risk remains unabated. Likewise, not only smoked tobacco products in the form of cigarettes, cigars, pipe and hookah, but also chewing tobacco, snuff or snus have negative effects on the cardiovascular system [4].

This negative effect of tobacco use on the cardiovascular system is due to several mechanisms:

- Increase in sympathetic nervous system activity, as evidenced by an increase in heart rate and blood pressure and a concomitant decrease in heart rate variability

- Disruption of endothelial function and increase in vascular stiffness

- prothrombotic activity (disturbance of coagulation and coagulation)

- Proinflammatory and prooxidant status (inflammatory factors and oxidative damage increase with tobacco use).

- proartherogenic effect on lipid profile (decrease in HDL cholesterol and increase in oxidized LDL)

- reduced oxygen supply due to the inhaled carbon monoxide (CO).

Effects of smoking cessation on cardiovascular risk.

Whether cardiovascular risk can adjust to the level of a lifelong nonsmoker after smoking cessation and how long this takes are controversial issues. There are studies that show a very strong risk reduction two to three years after quitting smoking. In turn, other studies suggest that cardiovascular risk remains somewhat higher than in nonsmokers 20 years after smoking cessation [7,8]. The reduction in cardiovascular risk depends on several factors. Individuals who used tobacco for many years never reach the cardiovascular risk of nonsmokers. Only early smoking cessation or smoking cessation after regular consumption of only 1-9 cigarettes/day can reduce cardiovascular risk to the level of nonsmokers [4].

In the Cardiovascular Health Study, it was observed that former heavy smokers (>32 Pack Years) were much more likely to develop heart failure or die than nonsmokers, even when smoking cessation occurred 15 years ago [9].

Interventions to support smoking cessation

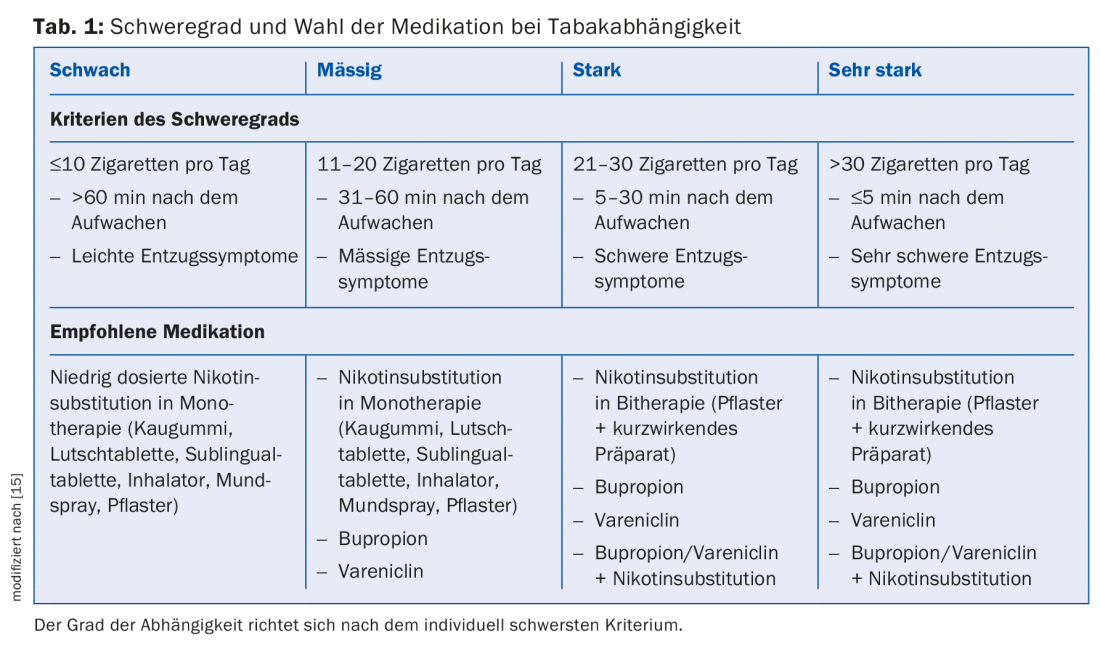

Brief intervention by a physician or nurse practitioner is already extremely effective and significantly improves the chances of smoking cessation success [10]. The chance of remaining tobacco-free is also increased by administration of a nicotine supplement or medication [11]. The most successful approach is a combination of specialized counseling and dispensing of a nicotine preparation and/or a medication to facilitate smoking cessation, such as bupropion (Zyban®) or varenicline (Champix®) (Table 1) [11]. This intensified smoking counseling can increase the chances of successful intervention [10].

Nicotine preparations, bupropion, and varenicline do not increase the risk of cardiovascular complications (eg, myocardial infarction, cerebrovascular insult, cardiovascular mortality) [10]. Zyban® and Champix® are permitted in Switzerland (one seven- or twelve-week therapy per 18 months) if the following limitations are met: Smoking behavior that meets the criteria of the dependence syndrome according to the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM) version IV or according to the International Classification of Diseases (ICD) version 10, plus additionally one of the following two criteria:

- Presence of a secondary disease of smoking or

- Presence of dependence for which the Fagerström test for nicotine dependence gives a score of 6 or more.

E-cigarette

“A cigarette that doesn’t burn” – that was the idea that led to the development of the e-cigarette. Electronic cigarettes, electric cigarettes or e-cigarettes have been known in Switzerland since around 2005. These consist of mouthpiece, cartridge (which contains the liquid to be vaporized with or without nicotine), vaporizer and battery. The batteries are partly also rechargeable through a USB port.

In principle, it is now assumed that e-cigarettes are less harmful than ordinary cigarette smoking. De facto, however, there is no certain information about the ingredients of an e-cigarette. The variability in the composition of the liquid is great in the different products, as well as in the different cartridges of the same brand. Ultimately, producers are not required to provide accurate information about the content. Roughly speaking, an e-cigarette contains propylene glycol and glycerol (to form the fog), natural or artificial flavors and (food) colorants, and possibly nicotine.

Nicotine-containing cartridges and refill liquids for e-cigarettes are not marketable as commodities in Switzerland: private individuals are not allowed to sell 150 cartridges or refill liquids. 150 ml of refill liquid to be imported into Switzerland (according to information letter No. 146 of the FOPH, as of 13.9.2010).

In a May 2009 investigation (FDA DPATR-FY-09-23 “Evaluation of e-cigarettes,” as of May 4, 2009), the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) tested cartridges from two suppliers and found that known carcinogens were present in detectable amounts. When smoking products with standardized nicotine content simulated for study purposes, very different amounts of nicotine were delivered, which is an indication of a lack of quality assurance processes in production. The study further revealed that all cartridges tested contained nicotine – even those advertised as nicotine-free.

Last but not least: So far, there is a lack of studies investigating the health risks associated with passive inhalation of the vapor.

Is the e-cigarette a smoking cessation aid?

The studies that have been conducted so far have not been able to prove that e-cigarettes are suitable for cessation therapy. The primary goal of tobacco cessation is to completely overcome nicotine dependence – however, this could only be achieved in a small percentage by using the e-cigarette [10–14].

Most individuals use cigarettes and e-cigarettes or become long-term “vapers” (i.e., e-cigarette users). The risk potential of dual use and long-term e-cigarette use has been understudied.

Whether e-cigarette vapor also causes passive exposure is unclear. It is possible that certain e-cigarettes are associated with lower risk for passively exposed individuals, but because there is so much variability among e-cigarettes as well as cartridges, it is difficult to draw a general conclusion.

E-cigarette: Trojan horse for smoking initiation

A downside of e-cigarettes is their potential to lead adolescents toward the habit of smoking. The use of e-cigarettes or e-shishas is rising sharply, especially among young people. The e-cigarettes look “cool” and the flavors like peppermint, fruit, coffee, vanilla and chocolate are very attractive. The path from e-cigarettes to tobacco cigarettes can be very short, so e-cigarettes should also be investigated as a possible smoking initiation product.

Literature:

- Jha P, et al: 21st-century hazards of smoking and benefits of cessation in the United States. N Engl J Med 2013; 368: 341-350.

- Yusuf S, et al: Effect of potentially modifiable risk factors associated with myocardial infarction in 52 countries (the INTERHEART study): case-control study. Lancet 2004; 364: 937-952.

- No authors listed: Environmental tobacco smoke and cardiovascular disease. Circulation 1991; 84: 956-959.

- Teo KK, et al: Tobacco use and risk of myocardial infarction in 52 countries in the INTERHEART study: a case-control study. Lancet 2006; 368: 647-658.

- Notara V, et al: Smoking determines the 10-year (2004-2014) prognosis in patients with Acute Coronary Syndrome: the GREECS observational study. Tob Induc Dis 2015; 13: 38.

- Zhang YJ, et al: Smoking is associated with adverse clinical outcomes in patients undergoing revascularization with PCI or CABG: the SYNTAX trial at 5-year follow-up. J Am Coll Cardiol 2015; 65: 1107-1115.

- Critchley J, Capewell S: Smoking cessation for the secondary prevention of coronary heart disease. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2003; (4): CD003041.

- Unal B, Critchley J, Capewell S: Impact of smoking reduction on coronary heart disease mortality trends during 1981-2000 in England and Wales. Tob Induc Dis 2003; 1: 185.

- Ahmed AA, et al: Risk of Heart Failure and Death After Prolonged Smoking Cessation: Role of Amount and Duration of Prior Smoking. Circ Heart Fail 2015; 8: 694-701.

- Patnode CD, et al: Behavioral Counseling and Pharmacotherapy Interventions for Tobacco Cessation in Adults, Including Pregnant Women: A Review of Reviews for the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force. Ann Intern Med 2015; 163: 608-621.

- Cornuz J, et al: Tobacco cessation: up-date 2011: part 1. Switzerland Med Forum 2011; 11: 156-159.

- Khoudigian S, et al: The efficacy and short-term effects of electronic cigarettes as a method for smoking cessation: a systematic review and a meta-analysis. Int J Public Health 2016; Jan 29 [Epub ahead of print].

- Bullen C, et al: Effect of an electronic nicotine delivery device (e cigarette) on desire to smoke and withdrawal, user preferences and nicotine delivery: randomised cross-over trial. Tob Control 2010; 19: 98-103.

- Caponnetto P, et al: EffiCiency and Safety of an eLectronic cigAreTte (ECLAT) as tobacco cigarettes substitute: a prospective 12-month randomized control design study. PLoS One 2013; 8: e66317.

- Clerc O et al: [Smoking cessation in general practice: the general practitioner is the best medicine!]. Praxis 2013; 102(10): 565-575.

HAUSARZT PRAXIS 2016; 11(4): 26-28

CARDIOVASC 2017; 16(1): 7-9