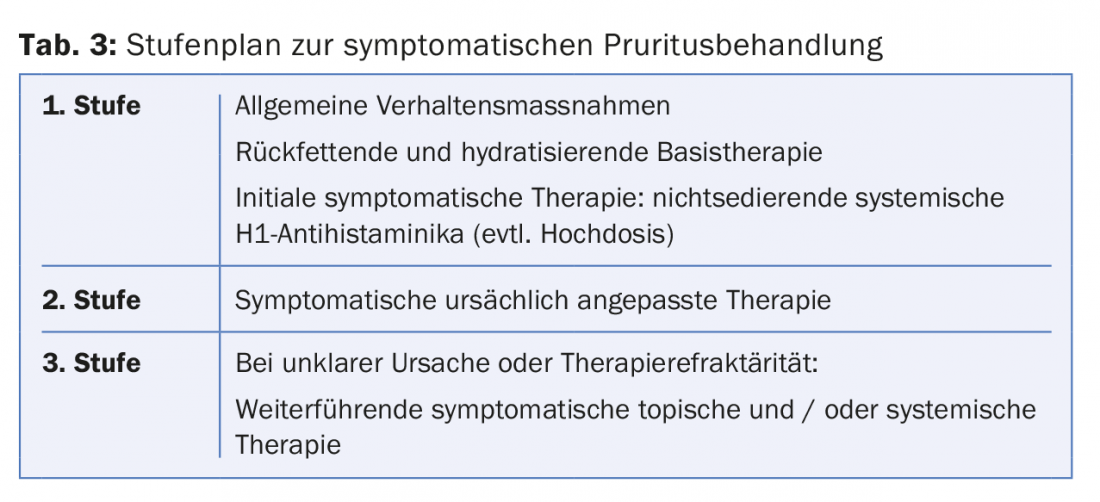

In order to treat pruritus adequately, the cause of the itching should be known. The clinical pruritus classification of the International Forum for the Study of Itch (IFSI) distinguishes three clinical groups of chronic pruritus. For symptomatic therapy of pruritus, one follows a step-by-step plan, which in the first stage includes rehydrating and hydrating basic therapy together with H1 antihistamines. In a second stage, causally oriented symptomatic therapy is applied, and in a third stage, in addition to phototherapy, drug treatments with anticonvulsants, antidepressants, and anti-inflammatory agents are used.

Pruritus (itching, itching) is considered the most common symptom of the skin: in a general population, chronic itching was found in almost one in six respondents. However, pruritus is not only common, it also has many causes: Itching can occur in skin diseases, in a variety of internal diseases, in pregnancy or as a result of medication [1].

The multitude of causes explains why there is no generally valid, uniform therapy for the treatment of pruritus. The rule is that in order to treat itching properly, you should know the cause . If this cause is treated, the itching usually disappears as well. Very often, however, patients suffer from chronic pruritus, the cause of which is not known even after a long clarification and which must be treated symptomatically. How to proceed with pruritus, especially with chronic pruritus, and what is recommended for treatment is described in detail at in the German AWMF guideline on chronic pruritus [2], which is newly published this year and in the creation of which the author of this article was involved.

Clinical classification of pruritus

Since effective pruritus therapy can only be provided when the aetiology is known, an existing pruritus should be properly identified, defined, and classified before any treatment.

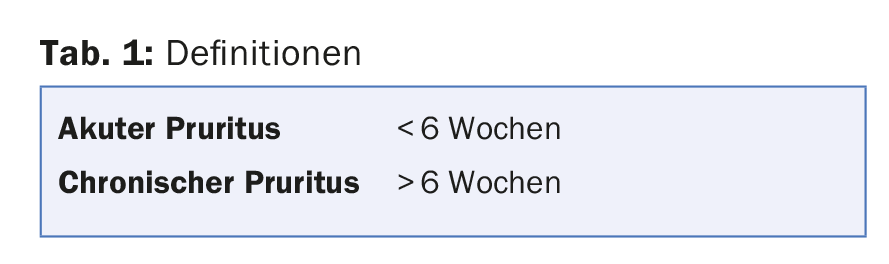

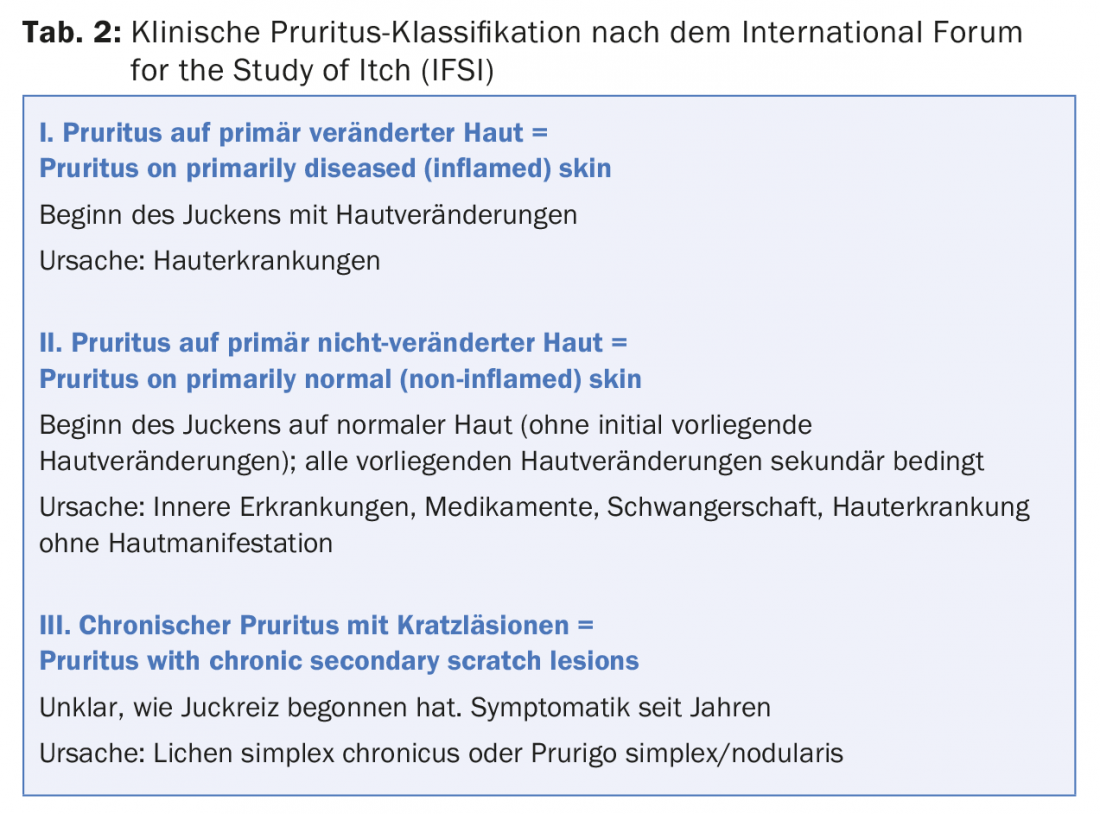

A first distinction is that of acute from chronic pruritus. This is defined by the duration of the itching: An itch that persists for less than 6 weeks is called acute pruritus. If the itching persists for more than 6 weeks, it is called chronic pruritus. The latter may have a wide variety of etiologies, which, in contrast to acute pruritus, are often not obvious and require further evaluation. In 2007, the International Forum for the study of itch (IFSI) proposed a classification of chronic pruritus that is now widely established internationally [3]. The IFSI classification allows – algorithm-like starting from the clinical appearance of the patient – a subdivision into three clinical groups. For each pruritus patient, the first step is to clarify whether the itching started on normal or primarily altered skin. This allows assignment to the following groups:

- Pruritus on primarily diseased (inflamed) skin: When the itching occurred, skin changes were present that led to the itching. The itching is found in the areas of the skin with inflammatory changes. The cause of the itching is an itchy skin disease that (still) needs to be diagnosed.

- Pruritus on primarily normal (non-inflamed) skin = Pruritus on primarily normal (non-inflamed) skin: When the pruritus occurred, no skin changes existed, the itching started on normal skin. Any skin changes that may be visible are secondary to scratching. Causes of itching are internal diseases [1] (e.g., terminal renal failure, cholestatic liver disease, lymphoproliferative disorders such as Hodgkin’s disease, polycythemia vera, etc.) or drugs. On primarily unchanged skin, itching can also occur during pregnancy. Last but not least, skin diseases must be considered that may manifest without initial skin lesions (e.g., senile pruritus in the context of xerosis cutis, minimal forms of atopic dermatitis, zoster or autoimmune bullous disease without blistering…). In the laboratory, a screening examination is necessary to avoid missing a triggering internal disease. In the precisely recorded medication history, it is necessary to look for medications whose new intake can be associated with the occurrence of itching. Atopy parameters (e.g., an atopy score) should always be recorded.

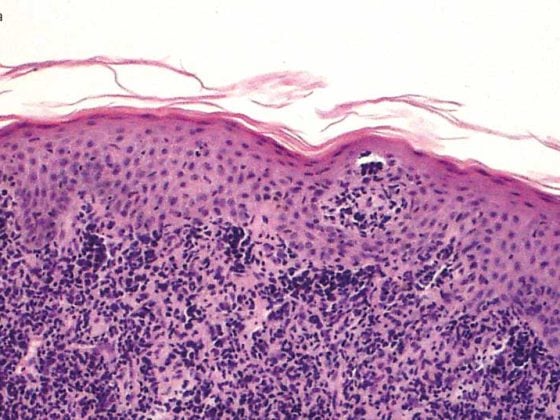

- Chronic pruritus with scratch lesions = Pruritus with chronic secondary scratch lesions: The itching has persisted for years. Secondary scratch lesions predominate in terms of findings. Classification into the first or second group is not possible. The clinical presentation is lichen simplex chronicus or prurigo simplex/nodularis [4].

Treatment of pruritus with known cause

In the case of pruritus on primarily inflammatory skin , treatment of the underlying skin disease usually also represents treatment of the itch.

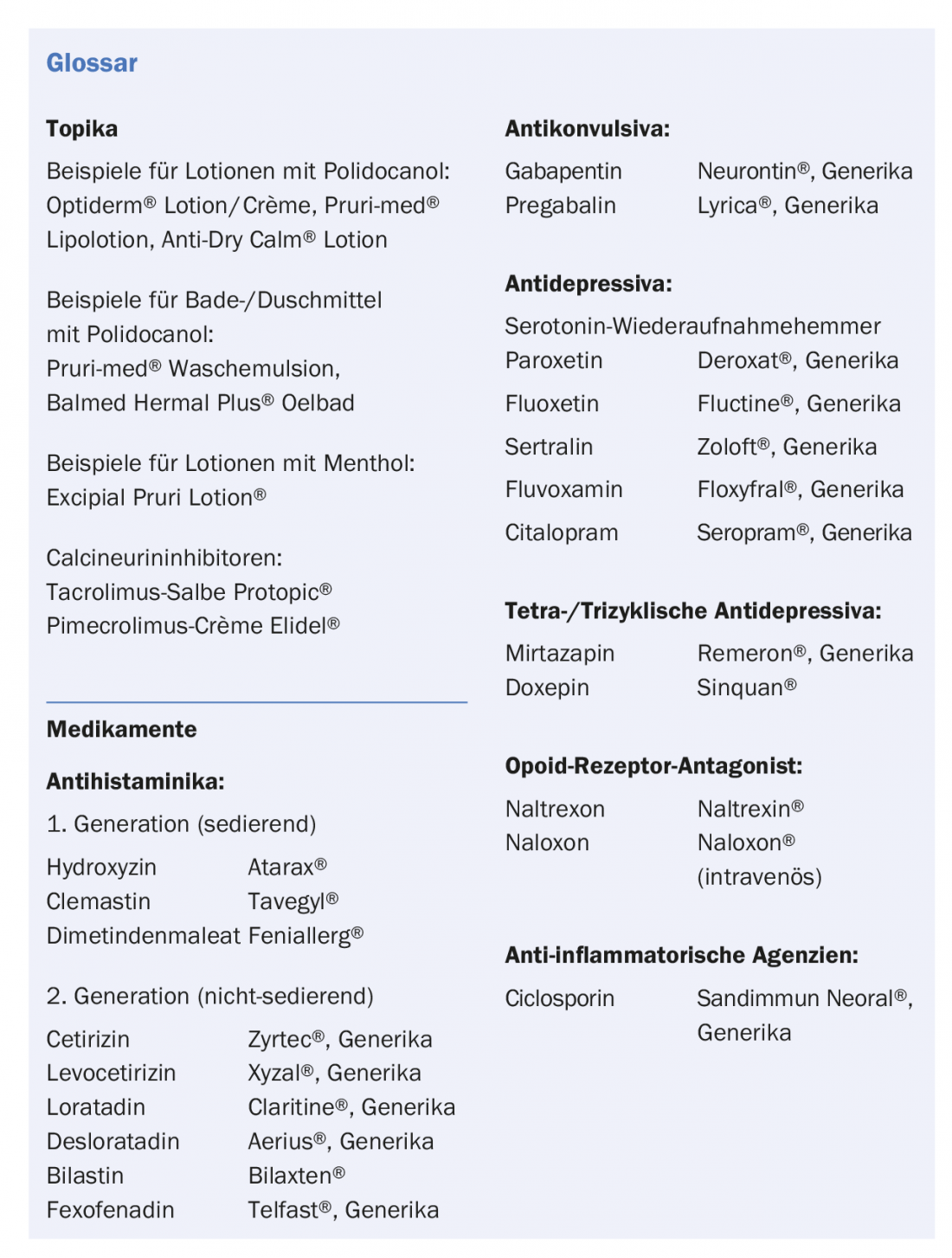

In atopic dermatitis , steroids and 2nd line calcineurin inhibitors are used for topical treatment, accompanied by systemic 2nd generation non-sedating antihistamines (cetirizine, loratadine…). In a further step, phototherapy can be used. In severe cases, systemic treatment will be necessary, with ciclosporin as the first-line therapeutic agent.

In psoriasis, topical treatment and phototherapy will also be tried first. Systemically, in addition to methotrexate and ciclosporin, biologics are of course used (TNF-alpha inhibitors, inhibitors of IL12/23 and IL-17).

In urticaria, antihistamines are the first choice from the outset. Separate guidelines exist for the treatment of the most important pruritic inflammatory dermatoses [5,6,7].

Pruritus on primarily noninflammatory skin should be treated for internal disease if it has been found to be causative. If medications are blamed for the itching, they must be omitted. In fact, addressing the cause of the itch often leads to rapid improvement in pruritus. For example, pruritus subsides rapidly after treatment of Hodgkin’s disease, as it does after discontinuation of a drug if it was responsible for the itching. Often, however, an internal disease, even if it has been identified as the trigger of the itch, cannot simply be treated away. In this situation, symptomatic measures are always recommended as a first step (see next section) and, depending on the clinical picture, certain therapeutic agents are recommended as a second step, which have been proven in studies or casuistry for the treatment of pruritus in this clinical picture.

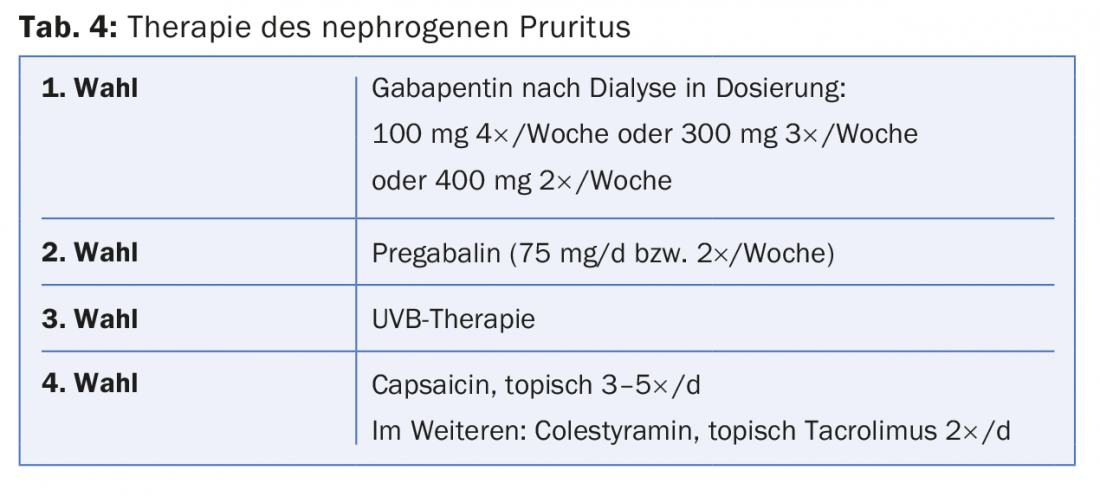

For nephrogenic pruritus, the new AWMF guideline rates gabapentin as the first choice before the use of pregabalin and before UVB phototherapy (Tab. 4) . Activated charcoal, which was still recommended in the first place in the last guideline, continues to be an alternative and can still be used easily.

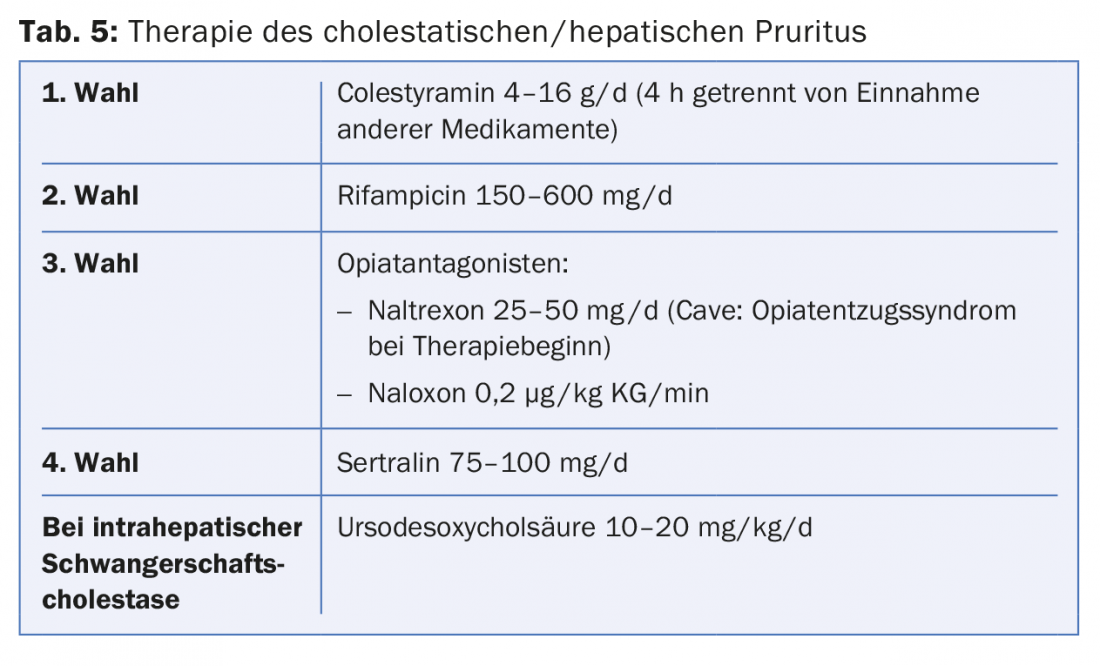

For cholestatic pruritus, colestyramine is considered the drug of first choice (tab. 5). In a next step, rifampicin is recommended, followed by the opiate antagonist naltrexone and then sertraline. Ursodeoxycholic acid is now only used for pregnancy pruritus on primary unchanged skin. Note that for the ursodeoxycholic acid preparations available in Switzerland, pregnancy is considered a contraindication in the technical information!

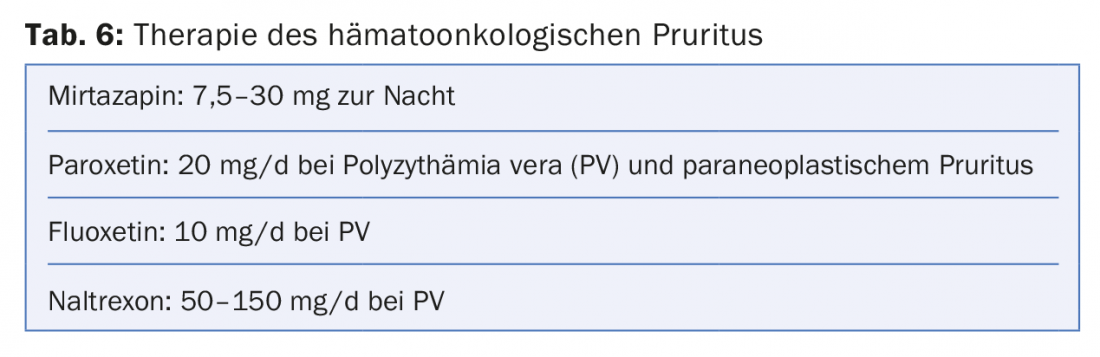

For hematologic neoplasms , either mirtazepine, paroxetine, or fluoxetine are recommended (Table 6) . Gabapentin is mentioned before mirtazepine for cutaneous lymphomas.

Neuropathic pruritus can be addressed either topically with capsaicin or systemically with gabapentin or pregabalin.

In pruritus with chronic scratch lesions, the current guideline recommends that steroids (especially occlusive) and pimecrolimus be considered first for topical therapy, with capsaicin and tacrolimus as the second choice. Systemically, the first choice is phototherapy (mostly UVB 311nm, but also PUVA). Medications may include gabapentin or pregabalin, and other drug options listed include ciclosporin, methotrexate, or naltrexone. Of course, other treatment modalities established in Switzerland such as intralesional steroids (Kenacort) or cryotherapy can be used very well in prurigo disease. However, there is insufficient evidence documented for this in studies and case reports .

Treatment of pruritus with unknown cause

In the case of chronic pruritus on primarily non-inflammatory skin, where the cause is (still) unclear, treatment will be symptomatic for the time being. A stepwise approach is recommended for symptomatic therapy (Tab. 3):

The first stage should be primarily recommendations that can be passed on to any itch patient, even regardless of the underlying internal disease:

- Thus, pruritus patients should avoid everything that leads to skin dehydration (especially too much washing and bathing) and that irritates the skin (clothing, irritating topicals). Negative stress should also be reduced.

- Mild washing syndets and the use of lipid-replenishing creams and lotions (taking into account the individual skin condition) are recommended as basic therapy. As additives in topicals, urea, polidocanol, camphor and menthol are often helpful against itching.

In addition to the basic lipid-replenishing and hydrating therapy, the antipruritic therapy in the first step also consists of the administration of an H1 antihistamine. According to the new guideline, only non-sedating antihistamines are recommended, but in the absence of a response to the standard dosage – as in allergology – up to a 4-fold dosage. The old sedating antihistamines, such as hydroxyzine, are explicitly no longer recommended.

This is remarkable because the latter are very common and popular in Switzerland for the treatment of pruritus and – also in the experience and opinion of the author of this article – often work better than the 2nd generation antihistamines in pruritus patients . Interestingly, this point is evaluated quite differently in the European pruritus guidelines. Here, hydroxyzine is listed as the first-choice antihistamine of a majority of dermatologists for the treatment of pruritus [8]. In the current expert group of the German guideline, however, it was claimed that a real good proof of the efficacy of sedating antihistamines had not been provided, whereas in studies the sedating effect was often listed as a negative side effect.

The second stage of symptomatic treatment includes all therapies adapted to a possible cause of pruritus.

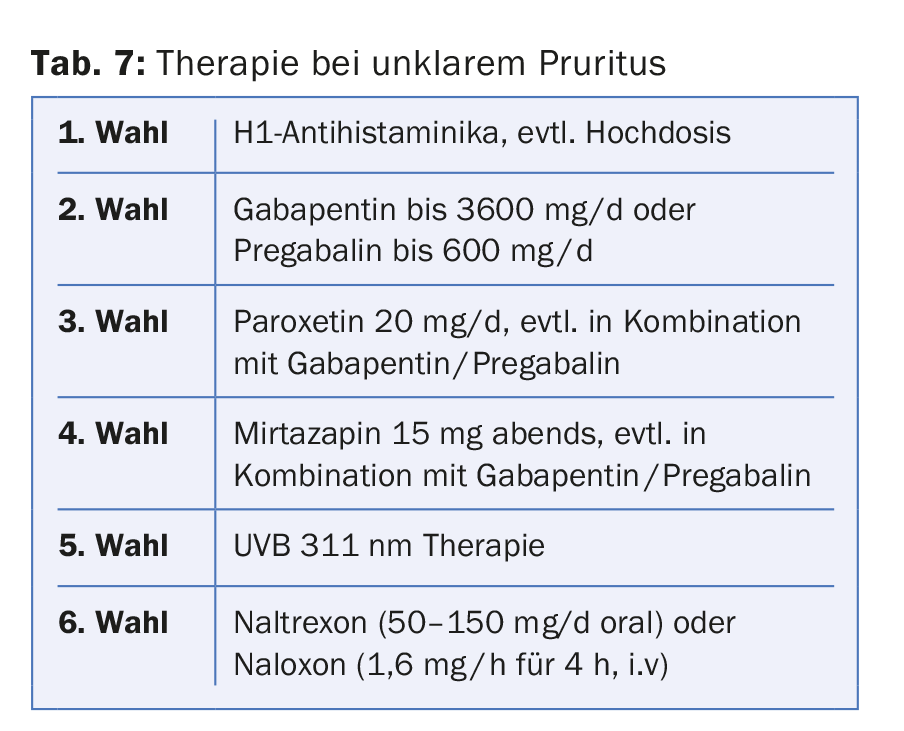

If the cause of the pruritus remains unclear despite all clarifications or if the pruritus remains refractory to therapy, there are further therapeutic options in the third stage, provided that the proposed treatments have not already been carried out (Tab. 7):

Medicinally, gabapentin can always be used first. In a next step, antidepressants are recommended (paroxetine or mirtazapine). Phototherapy with UVB 311nm is the next option. Finally, naltrexone can also be tried.

Selected recommendations for pruritus therapy in the new AWMF guideline

In the new AWMF guideline chronic pruritus, recommendations are made for virtually all therapies used for pruritus, which were given as strong, moderate or weak recommendations by a group of experts in a consensus process. Recommendations are based on treatment successes documented in studies. Some relevant therapies should be mentioned here:

Additives in the basic treatment: Menthol, camphor, lidocaine and polidocanol are listed here for topical treatment. Their use can be considered.

Topical steroids: they are usually the treatment of choice for inflammatory dermatoses. They may also be recommended for short-term use in secondary inflammatory scratch lesions for pruritus that has not occurred in the setting of an inflammatory skin disease. Similarly, topical calcineurin inhibitors can also be used as a 2nd choice.

Systemic antihistamines: as mentioned above, only non-sedating antihistamines are now recommended, but their use can be considered up to 4 times the standard dosage if needed. Evidence in studies is lacking in this regard. In addition, the administration takes place in off-label use. The use of sedating antihistamines is – as already mentioned – no longer recommended.

Systemic steroids: these often have to be used for months in certain inflammatory dermatoses that can also be itchy, such as bullous pemphigoid or DRESS syndrome. They can also be used for treatment of severe chronic pruritus without underlying skin disease, but only as part of short-term therapy. The expert group would like to deliberately refrain from prolonged use because of the steroid side effects. However, it is undisputed that in exceptional cases systemic steroids must be used if the patient’s level of suffering is very high.

Phototherapy: It is helpful in itchy inflammatory dermatoses, as well as in internal diseases leading to itching and also in prurigo diseases (or chronic scratch lesions). In all forms, the treatment with UVB 311nm, which is most commonly performed in Switzerland, is well applicable. However, the consensus group has come to only a weak recommendation on the use of phototherapy.

Gabapentin and pregabalin: Here, a strong recommendation is given for use in nephrogenic and neuropathic pruritus, even if the use (in Germany) is off-label. In addition, both drugs can be recommended for pruritus of other aetiology.

Antidepressants: a medium-strong recommendation was made for these medications. The serotonin reuptake inhibitors (specifically paroxetine, sertraline, and fluvoxamine) have shown good efficacy in studies and, based on study documentation, appear to have better efficacy in pruritus treatment than the tetra- or tricyclic antidepressants mirtazapine and doxepin, but these can also be used for pruritus of various aetiologies.

opioid receptor antagonists: In Switzerland, naltrexone can be used orally here. Based on data from individual studies, naltrexone may be recommended or at least considered in certain situations. However, the side effects, which almost always occur, are uninviting for treatment. In the author’s experience, naltrexone ultimately had to be discontinued in every patient because of side effects, even though individual cases had actually shown improvement in itching.

Conclusion: Especially the recommendations on the use of systemic pruritus therapeutics clearly show where the limits of an evidence-based guideline lie: Basing recommendations on evidence from studies leads to the recommendation of treatments for which efficacy has been shown in individual recent studies. However, because of the side effects, the therapies can hardly be used in everyday clinical practice and are often unreasonable for patients. Conversely, treatment procedures that have worked well for decades but for which no data can be found from more recent studies or where old studies no longer meet the requirements of today’s study designs are omitted. Therefore, the same applies here: Not everything that is good in studies is always good for patients in everyday clinical practice!

Literature:

- Streit M, et al: Pruritus sine marteria. Pathophysiology, diagnostic assessment and therapy. Dermatologist. 2002; 53(12): 830-49.

- Ständer S, et al: S2k-Leitlinie zu Diagnostik und Therapie des chronischen Pruritus. AWMF online 2016 (in process).

- Ständer S, et al: Clinical classification of itch: a position paper of the International Forum for the Study of Itch. Acta Derm Venereol. 2007; 87(4):291-4.

- Schedel F, et al: Clinical definition and classification. Dermatologist 2014; 65: 684-690.

- Werfel T, et al: S2k guideline on diagnosis and treatment of atopic dermatitis – short version. Allergo J Int. 2016;25: 82-95.

- Nast A, et al: Deutsche Dermatologische Gesellschaft (DDG); Berufsverband Deutscher Dermatologen (BVDD): Evidence-based (S3) guidelines for the treatment of psoriasis vulgaris. J Dtsch Dermatol Ges. 2007; 5 Suppl 3: 1-119.

- Zuberbier T, et al: European Academy of Allergy and Clinical Immunology; Global Allergy and Asthma European Network; European Dermatology Forum; World Allergy Organization: The EAACI/GA(2) LEN/EDF/WAO Guideline for the definition, classification, diagnosis, and management of urticaria: the 2013 revision and update. Allergy. 2014; 69(7): 868-87.

- Weisshaar E, et al: European guideline on chronic pruritus. Acta Derm Venereol. 2012; 92(5): 563-81.

DERMATOLOGIE PRAXIS 2016; 26(6): 20-25