Anxiety disorders are among the most common psychiatric disorders. Nevertheless, they are often diagnosed and treated years later. Exclusion of physical disease consisting of at least a detailed history, laboratory, and ECG is recommended. Cognitive behavioral therapy has the best evidence of efficacy for all anxiety disorders and is therefore psychotherapy of choice. SSRIs and SSNRIs are the first choice in the treatment of anxiety disorders due to the best evidence as well as favorable side effect profile. Benzodiazepines are effective for anxiety disorders, but are recommended only for short-term use because of the potential for dependence; only in justified cases of treatment resistance can they be used for longer periods.

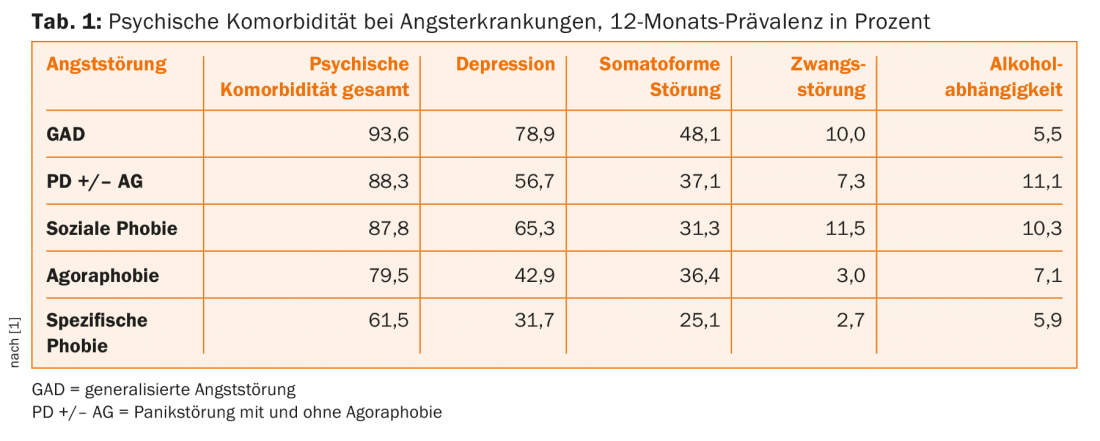

Anxiety disorders represent the most common psychiatric disorders in the general population, with a prevalence of up to 20% [1]. They include panic disorder with and without agoraphobia (PDA, PD), generalized anxiety disorder (GAD), social phobia (SP), and specific phobias. Despite the high prevalence, the diagnosis of an anxiety disorder is often made only after a long latency period and thus leads to long-term restriction of the affected person’s scope of action, chronification of the suffering and high socioeconomic costs. Women are usually affected twice as often as men. Anxiety disorders are often comorbid with other mental illnesses (tab. 1). In particular, the presence of substance abuse, depression, or personality disorders can significantly complicate treatment.

Diagnostics

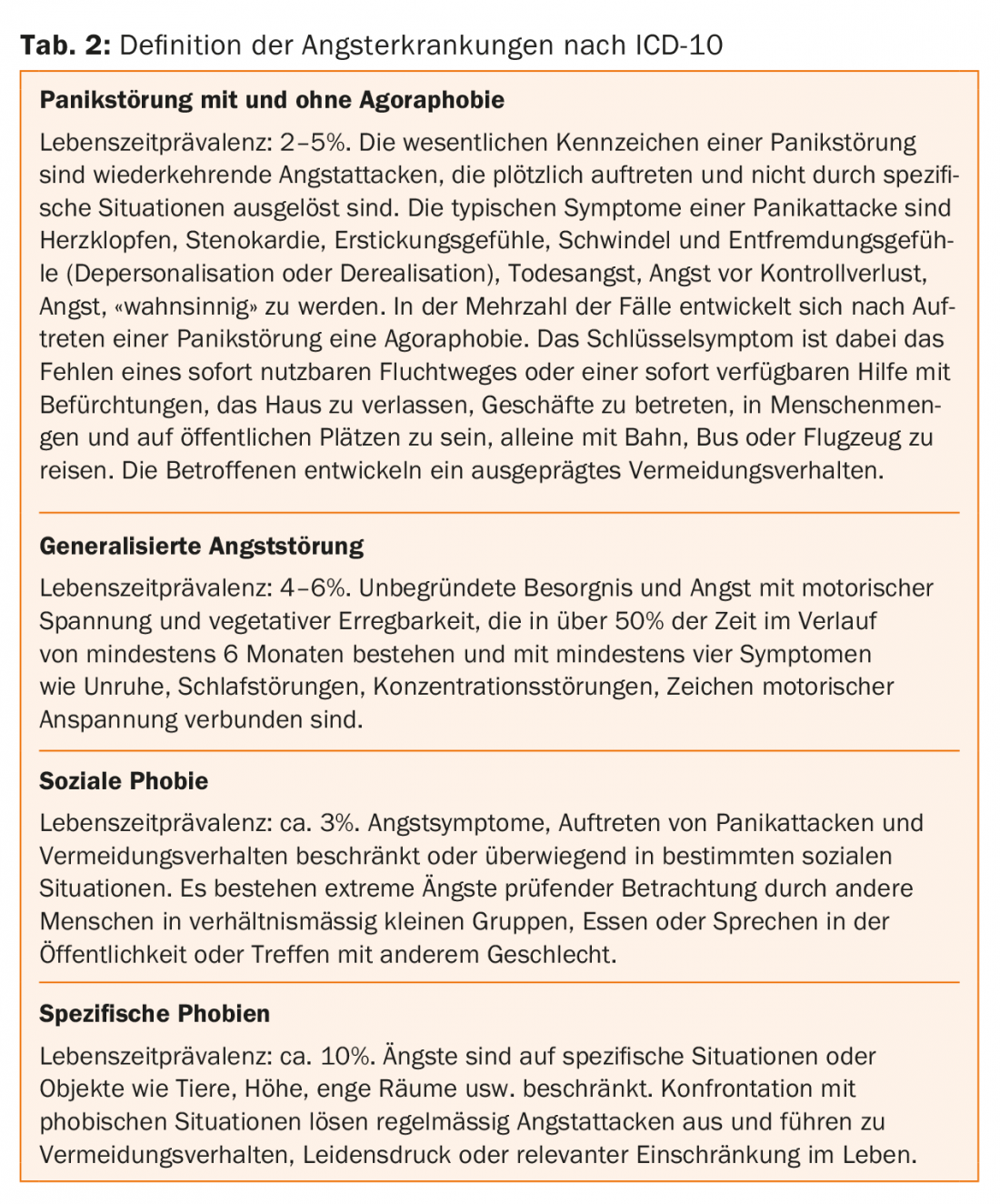

In principle, the ICD-10 criteria apply to the clinical diagnosis of anxiety disorders (Tab. 2). For differential diagnosis of somatic diseases, the following examinations are recommended as a minimum standard: a detailed history, physical examination, laboratory with blood count, electrolytes, blood glucose and thyroid parameters, and an ECG. These examinations may be supplemented by cranial magnetic resonance imaging, pulmonary function, EEG, and other examinations as appropriate, depending on clinical symptoms. The most important diseases to be excluded are pulmonary and cardiovascular diseases as well as endocrine and neurological disorders.

Principles of therapy

The treatment recommendations for anxiety disorders in adults presented below are based on the guidelines of the European professional societies: SGAD, SGBP and SGPP [2], the World Federation of Societies of Biological Psychiatry [3], the British Association of Psychiatry [4] and the German S3 guideline for the treatment of anxiety disorders [5] (for evidence level see Tab. 3).

For anxiety disorders other than specific phobias (cognitive behavioral therapy, CBT, only), both psychotherapy (CBT) and pharmacotherapy can be recommended as first-line therapy because of comparable efficacy. The preference of the informed patient as well as the severity of the disease represent an essential basis for the decision on the choice of the form of therapy.

Non-pharmacological treatments

In general, psychotherapeutic treatment is recommended for all anxiety disorders, with the best level of evidence for CT. This does not exclude the possibility that other psychotherapeutic methods may also be effective, but the effectiveness of those has not yet been sufficiently scientifically proven. The duration of psychotherapy generally depends on the severity of the illness, comorbidity and individual psychosocial conditions of the patient.

Psychoeducation is the most important introductory measure at the beginning of therapy. The goal is to convey a model of the disease that is understandable to those affected, in order to improve the way they deal with their anxiety symptoms. Exposure treatment (such as flooding and systematic desensitization) is particularly effective for phobic disorders such as agoraphobia, sociophobia, and specific phobias. Specific cognitive approaches have been developed against anxiety that is not situation or object related. KVT can also be supplemented with relaxation techniques.

A positive influence on anxiety levels was also shown for regular endurance sports activities. By increasing the general physical fitness of the patients, a better general condition and reduction of muscle tension can be achieved. From the behavioral therapy point of view, the conscious confrontation of the affected person with symptoms that also occur during panic attacks (e.g., tachycardia, hyperventilation, hyperhidrosis) is achieved. False attributions and misinterpretations of these physiological bodily reactions can thus be specifically addressed by behavioral therapy.

Drug therapy

Anxiolytic antidepressants have no dependence potential and are used primarily in therapy. From this group, selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) and selective serotonin-norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors (SSNRIs) are first-line agents for anxiety disorders, due to their good tolerability and favorable side effect profile. Tricyclic antidepressants (TCAs) have good efficacy but are less well tolerated. Benzodiazepines should be administered only when needed, if possible, or if taken daily, for no longer than six weeks because of the potential for dependence. Benzodiazepines may be administered for a longer period of time if anxiety symptoms are refractory to treatment and other therapeutic options have been exhausted. Despite frequent prescription, phytotherapeutics lack sufficient evidence of efficacy in the treatment of anxiety disorders to date.

The recommended duration of treatment is at least six months, twelve months is optimal. The dose of maintenance therapy for SSRIs and SSNRIs should be the same as the dose successful in the acute phase. In the reduction phase, a slow approach is recommended, otherwise significant discontinuation symptoms may occur and lead to destabilization of the treatment outcome.

Selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs): When treating with SSRIs, attention should be paid to the fact that patients with anxiety disorders generally exhibit significant single-dose effects, including agitation, nervousness, and exacerbation of anxiety symptoms. Therefore, it is recommended to choose very low initial doses and slow dose increase. It is helpful to educate patients about the dosing effects to improve compliance. During treatment with SSRIs, regular ECG checks should be performed to rule out QTc time prolongation. SSRIs may impair platelet aggregation, resulting in prolonged bleeding time. In patients who have a history of bleeding events or are currently being treated with aggregation inhibitors, the indication should be strictly reviewed. Other relevant side effects include hyponatremia and, in rare cases, syndrome of inadequate ADH secretion (SIADH). In particular, side effects such as sexual dysfunction and sporadic weight gain may have a negative impact on patient compliance.

Selective serotonin-norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors (SSNRIs): venlafaxine is approved for the treatment of PDA, SP, and GAD, and duloxetine for the treatment of GAD. Slow dosing is also recommended for SSNRI. Patients often complain of increased sweating and night sweats and, similar to SSRIs, sexual dysfunction. Furthermore, an increase in blood pressure may occur, which is why regular blood pressure checks are recommended, especially in cases of pre-existing hypertension.

Tricyclic antidepressants (TCAs): TCAs are characterized by comparable efficacy to SSRIs and SSNRIs, but have a less favorable side effect profile. In addition to cardiac side effects, anticholinergic side effects, such as dry mouth and constipation, are often a reason for discontinuing therapy. In elderly patients in particular, the internal risk profile must be carefully reviewed and attention paid to the cognitive status, since a marked deterioration to the point of delirium may occur. The substance opipramol also belongs to the group of TCAs. This substance is also approved for psychosomatic disorders, which is why it is often used in patients with psychosomatic disorders. is used with pronounced physical complaints.

Anticonvulsants: pregabalin is currently the only anticonvulsant approved for the treatment of an anxiety disorder (GAD). The exact mode of action of pregabalin is not yet fully understood. Currently, it is thought that binding of the compound to the presynaptic alpha2beta subunits of voltage-gated calcium channels leads to reduction of neurotransmitter release, such as norepinephrine, glutamate, and substance P (hence the name calcium channel modulator). Limiting the use of pregabalin are case reports indicating a potential risk of dependence.

Previous studies with other anticonvulsant agents in patients with anxiety disorders suggest that pregabalin and gabapentin additionally show therapeutic effects in social phobia and valproic acid in panic disorder. These agents are reserved for use in the event of treatment failure under standard medication. The exception is anxiety patients with comorbid bipolar disorder, in which case anticonvulsants could be the primary therapeutic approach.

Treatment for special groups of patients

In elderly patients, particular attention must be paid to concomitant physical diseases as well as drug interactions. Overall, lower doses should be chosen and care should be taken to increase psychotropic drugs cautiously. Substances with anticholinergic effects should be avoided because of their delirogenic properties and cardiac/internal side effects. The same applies in particular to the presence of dementia.

In pregnancy, the indication for psychopharmacological treatment should be strict. Overall, treatment with SSRIs and TCAs has been shown to be relatively safe, despite reports of possible preterm birth, organ abnormalities, or perinatal complications such as postnatal neonatal withdrawal syndrome. Data on the influence of psychotropic drugs on the rate of spontaneous abortions are inconsistent. A clear teratogenic risk has not been demonstrated for the commonly used antidepressants. Based on individual case reports on a possible teratogenic effect of benzodiazepines, the substances diazepam and chlordiazepoxide, for which many years of experience are available and which appear to be relatively safe, should be preferred in justified exceptional cases.

SSRIs and TCAs may also be administered during breastfeeding, as relatively low concentrations in infants have been demonstrated for sertraline and amitriptyline, among others. However, the study situation may not be sufficient to give a safe all-clear. Infants should therefore be closely monitored when mothers are taking psychotropic drugs. For more information on the use of psychotropic drugs during pregnancy and lactation, see www.embryotox.de.

Procedure in case of non-response to pharmacological treatment

As a rule, one speaks of therapy resistance to pharmacological treatment if the disease symptomatology is not relevantly improved after at least two sufficiently long and sufficiently dosed treatment attempts with substances of different effect classes. If treatment resistance is identified, the following points should be checked: Is the diagnosis correct; are there comorbidities that complicate treatment; is there compliance regarding medication use; are the duration of therapy and dose (serum levels) adequate. In particular, the latter with therapeutic drug monitoring (TDM) is increasingly a necessary component of modern pharmacotherapy, as often due to individual metabolism (e.g., genetic variants of CYP proteins) or interactions with adjunctive drugs, the effective level increase in the blood and consequently in the CNS does not occur. Treatment of comorbid mental illnesses, such as personality disorders or obsessive-compulsive disorder, should be considered.

To date, well-defined strategies for treatment in the absence of response to first-line pharmacotherapy are lacking. Current recommendations suggest that consideration may be given to switching to psychotherapy, switching to another substance (SSRI, SNRI, or TCA), or a combination of substances (see specific recommendations). For combination therapy or augmentation strategies [6], the data situation is so far inconclusive.

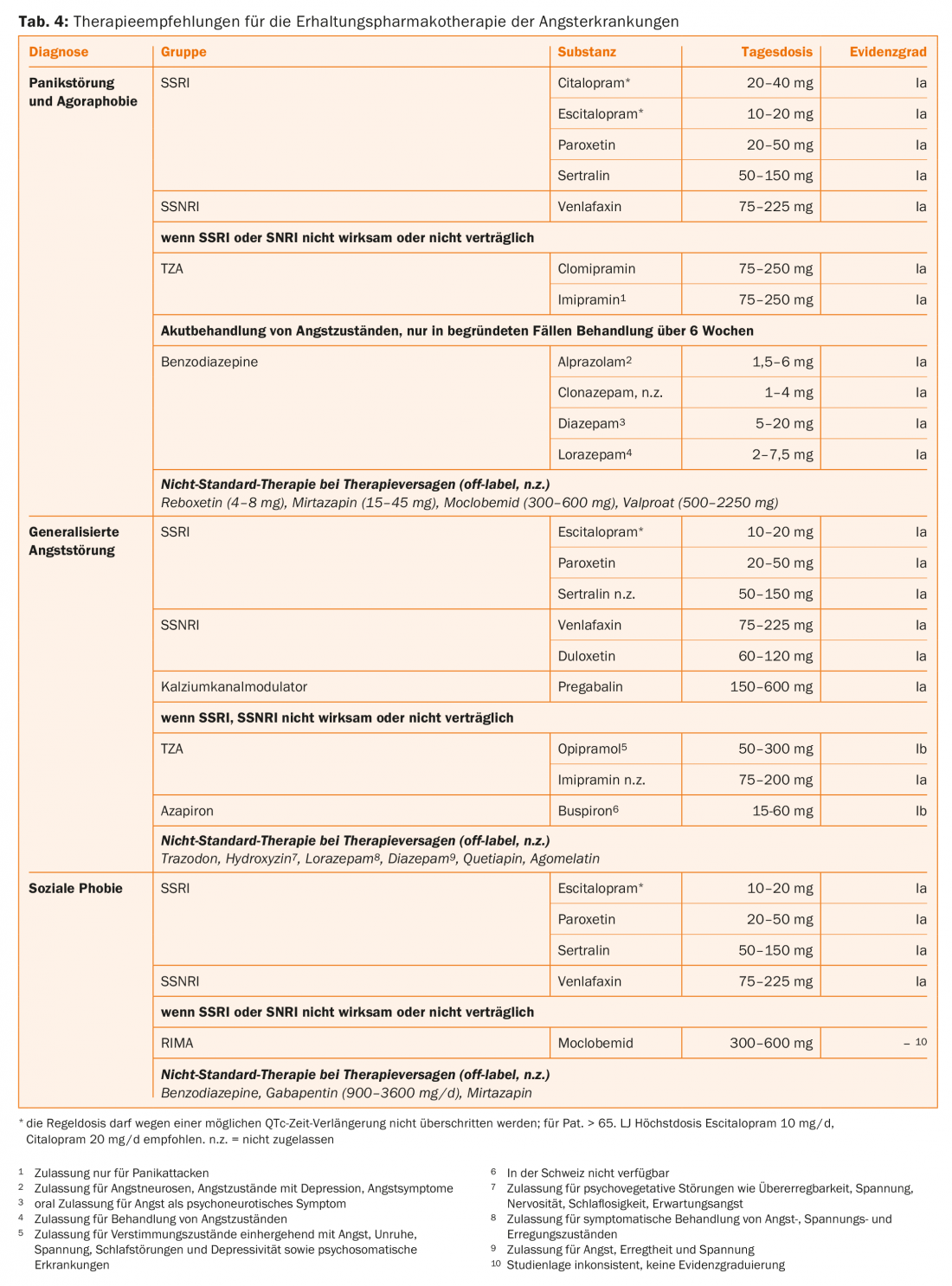

Specific recommendations (Tab. 4)

Panic disorder with and without agoraphobia: KVT (Ia), endurance training (3-5/week) as a measure with additional positive benefits, and information about self-help and family groups are recommended.

In the acute treatment of panic attacks, lorazepam (1-2.5 mg) and alprazolam (0.5-2 mg, approved for anxiety neurosis) are usually used.

In maintenance therapy, SSRIs and venlafaxine are primarily recommended; TCAs are second choice.

In cases of treatment resistance, the use of unapproved agents with limited evidence such as reboxetine, mirtazapine, moclobemide, and valproic acid in combination with SSRIs or TCAs is possible. Other “off-label” options in treatment-resistant patients include opipramol, pregabalin, hydroxyzine, and combination of TCAs and SSRIs, augmentation of SSRIs with the beta-blocker pindolol, and addition of atypical neuroleptics. In principle, however, the use of neuroleptics is not recommended. There is no positive evidence for conventional neuroleptics, and the data are inconsistent for atypical neuroleptics.

The efficacy of combination therapy of psychotherapy and pharmacotherapy for PD/PDA is superior to the use of monotherapy in each case and can be recommended on the basis of evidence.

Generalized anxiety disorder: cognitive behavioral therapy should be used for GAD (Ia). Psychodynamic therapy (IIa) may be used when CT fails. There is a lack of comparisons between Internet-based therapy and therapy delivered in person by the therapist. However, in comparisons with waiting lists, Internet-based CT was superior, making it a good option for patients who do not have immediate access to therapists. Direct comparative studies between individual and group therapy are lacking so far, so both therapy settings can be recommended depending on the patient’s preference.

The SSRIs paroxetine and escitalopram and SSNRIs duloxetine and venlafaxine are considered the agents of choice for GAD (Table 4). A positive effect has been demonstrated for sertraline, but the substance is not approved for GAD. The anticonvulsant pregabalin has an approval for GAD (Ia). If there is no response to SSRIs and SNRIs, the TCAs imipramine (Ia) or opipramol (Ib) can be used. For the 5HT1A agonist buspirone, the results are not consistently positive, so it is recommended as a lower priority (Ib). Trazodone (100-300 mg) and hydroxyzine (25-75 mg) are other off-label agents for treatment failure.

Positive effects in GAD have been described for the newer SSRI vortioxetine (approved for depression) and for agomelatine (selective melatonin receptor 1 and 2 agonist) [7,8]. The 5HT1A agonist buspirone and the antihistamine hydroxyzine do not have approval for specific anxiety disorders, but efficacy has been shown for both agents in the acute treatment of GAD.

Evidence for the use of atypical neuroleptics is insufficient to make a recommendation. There are positive reports for quetiapine. Due to the lack of approval, this is a remedy only in case of failure or non-adherence to standard therapy, taking into account the side effect profile, such as weight gain as well as sedation. Isolated studies with sometimes conflicting results also exist for augmentation with risperidone and olanzapine in refractory patients. Other unapproved reserve medications with limited evidence include valproate and bupropion.

Social phobia: KVT is considered the psychotherapeutic method of choice for patients with SP (Ia). Both acute and long-lasting effects have been demonstrated. There is no firm evidence that group therapy is more effective than individual VT. However, important components of CT are more feasible in groups, such as safety and skills training and some exposure approaches. There is preliminary evidence for the potential efficacy of Internet-based CT, which is particularly more accessible to patients with social phobia because of their contact aversion. For psychodynamic therapy, sufficient proof of efficacy is lacking so far.

Pharmacologically, the SSRIs escitalopram, paroxetine, and sertraline and the SSNRI venlafaxine are considered first-line treatments (Ia). Fluvoxamine showed efficacy in several studies, and citalopram was effective in one study, but neither agent is approved for SP. The reversible inhibitor of monoamino oxidase A (RIMA) moclobemide is approved for SP. However, because the study evidence is inconclusive, it is recommended as a lower priority. For SP, there is no evidence of efficacy of TCAs and beta-blockers to date. Insufficient but partially positive evidence was shown for the following substances not approved for SP: Pregabalin (only in the high dose range of 600 mg/d), mirtazapine, gabapentin, and olanzapine.

Specific phobias: Specific phobias are primarily treated with CT using exposure procedures in vivo (Ia). When in vivo interventions are not available, virtual reality exposures can be performed by donning specific video goggles. Basically, there is no evidence to date on the efficacy of pharmacotherapy for specific phobias. Only in cases with very severe disease may SSRIs be indicated, but evidence of efficacy is still lacking.

Literature:

- Jacobi et al: Prevalence, co-morbidity and correlates of mental disorders in the general population: results from the German Health Interview and Examination Survey (GHS). Psychol Med 2004; 34(4): 597-611.

- Keck et al: The treatment of anxiety disorders. Switzerland Med Forum 2011; 11(34): 558-566.

- Bandelow et al: Guidelines for the pharmacological treatment of anxiety disorders, obsessive-compulsive disorder and posttraumatic stress disorder in primary care. Int J Psych Clin Pract 2012; 16(2): 77-84.

- Baldwin et al: Evidence-based pharmacological treatment of anxiety disorders, post-traumatic stress disorder and obsessive-compulsive disorder: A revision of the 2005 guidelines from the British Association for Psychopharmacology. J Psychopharmacol 2014; 28(5): 403-39.

- Bandelow et al: German S3 guideline treatment of anxiety disorders. www. awmf.org. 2014.

- Patterson et al: Augmentation strategies for treatment-resistant anxiety disorders: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Depressed Anxiety 2016; 33(8): 728-36.

- Pae et al: Vortioxetine, a multimodal antidepressant for generalized anxiety disorder: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Psychiatr Res 2015; 64: 88-98.

- Levitan et al: Profile of agomelatine and its potenzial in the treatment of generalized anxiety disorder 2015; 11: 1149-55.

InFo NEUROLOGY & PSYCHIATRY 2016; 14(6): 30-35.