Due to the increasing aging of the population as well as improved medical care, the number of patients undergoing renal replacement procedures has increased in recent years. At the end of 2015, there were approximately 4100 patients on a dialysis program, with 423 patients on home dialysis (mostly peritoneal dialysis) [1] and the remainder on center hemodialysis. In addition, there are approximately 5000 patients in Switzerland with a functioning transplant. Many medical specialties are involved in the care of patients with chronic renal failure. For stage CKD 1-3, the primary care physician is the primary caregiver, and then for stage CKD 4+5 (dialysis patients), care is more likely to be with the nephrologist (Fig. 1). If renal function is <30% (GFR <30 ml/min.), referral to a nephrologist should be made so that careful preparation of the patient for a renal replacement procedure can be made [2].

As a rule, chronic dialysis is started when the GFR is between 8-12 ml/min., whereby the decision to start is not based solely on laboratory values [3]. In asymptomatic patients, the indication for starting dialysis can be made with restraint [4]. An absolute indication is hyperkalemia that cannot be controlled with conservative measures, hypervolemia that cannot be controlled with diuretics (especially in cardiorenal syndrome). With good cooperation between nephrologist, general practitioner and patient, the clinical picture of uremic pericarditis or uremic encephalopathy should not occur; both clinical conditions would be an emergency indication for dialysis initiation.

Peritoneal dialysis [5]

- CAPD = continuous ambulatory peritoneal dialysis

- APD = automated peritoneal dialysis

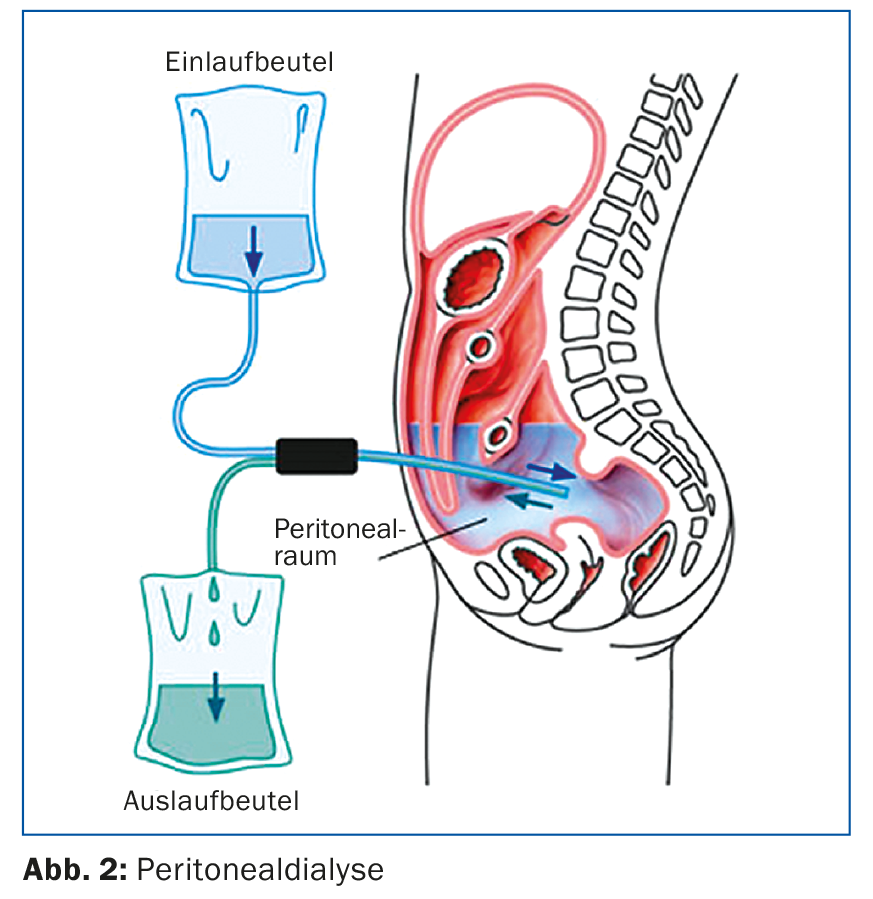

Peritoneal dialysis has no place as an acute dialysis procedure in adults. In contrast, the procedure is well established in chronic renal failure requiring dialysis. In Switzerland, the proportion of peritoneal dialysis patients has increased in recent years (10-12%). Prospective randomized trials directly comparing mortality and morbidity between PD and HD do not exist, but at least in the early years of renal replacement therapy, the procedures appear equivalent. In severe heart failure (and circulatory instability during HD) and lack of hemodialysis vascular access options, PD is preferable. A good alternative to center hemodialysis is nocturnal APD, especially in younger working patients.

Figure 2 shows the technical aspects: PD is performed via an intraperitoneal, usually laparoscopically inserted dialysis catheter. The procedure uses the peritoneum as a semipermeable membrane to remove metabolites via diffusion and osmosis. In peritoneal dialysis, the patient’s compliance is very essential, as the patient performs the therapy himself. He is trained and monitored by specialized nursing staff, and if stable, nephrological checks and consultations then take place every 4-6 weeks.

A possible advantage of peritoneal dialysis over hemodialysis is that the residual function resp. residual diuresis is preserved longer. For this reason, it is important that as few radiological examinations as possible are performed with iodinated contrast medium. Non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs should also be avoided to preserve residual function, which is important for peritoneal dialysis. In the case of complications of peritoneal dialysis, the nephrology center is usually responsible, especially for catheter problems such as catheter dislocation or catheter leakage. With current peritoneal dialysis systems, peritonitis is rare but still dangerous [5]. If cloudy dialysate or abdominal pain occurs, the dialysate should be examined as an emergency and antibiotic therapy should be started (usually intraperitoneal, hospitalization can often be avoided).

Hemodialysis

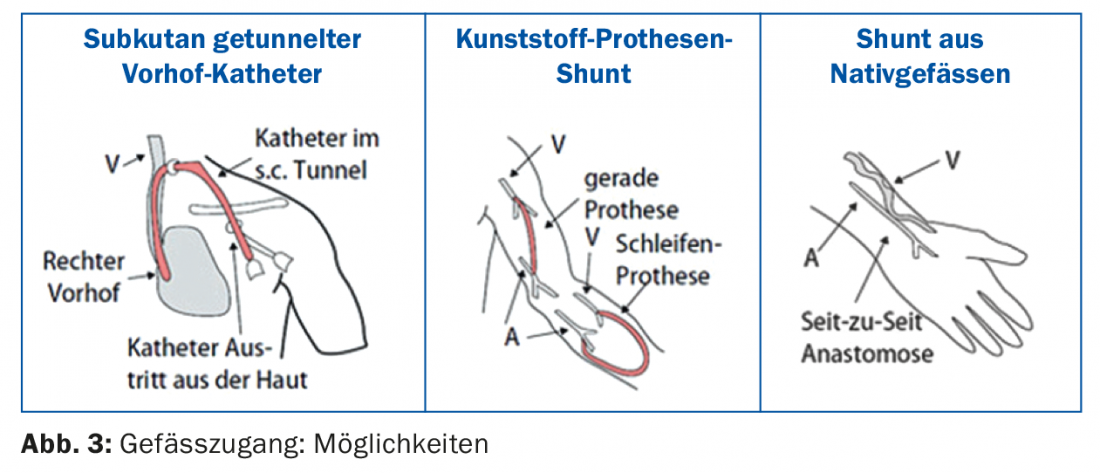

For most patients, hemodialysis is performed in a dialysis center (center dialysis); only a few patients perform dialysis at home (home hemodialysis). A single hemodialysis treatment takes 3.5-4.5 hr depending on residual function and other individual factors. Three hemodialysis sessions are usually performed per week. In most centers it is technically possible to perform a so-called hemodiafiltration (detoxification by combining hemodialysis and hemofiltration). Efficient dialysis requires vascular access [6], which provides sufficient blood flow (>300 ml/min.) is allowed. Vascular access is still referred to as the “horse’s foot of dialysis” due to various technical problems. The various options are shown in Figure 3 : If no shunt is available at the start of dialysis, the procedure is performed via a subcutaneously tunneled atrial catheter. The advantage is that dialysis can be started immediately. Especially in elderly patients and patients with very poor peripheral vascular conditions as well as severe heart failure, an atrial catheter may also be the primary choice of vascular access. After each dialysis, the catheter volumes are blocked with a special solution (e.g. Liquemin or citrate solution). Manipulation of long-term dialysis catheters should only be performed by trained dialysis personnel, otherwise complications such as catheter dysfunction or catheter infections are preprogrammed [7].

The best vascular access remains a native arterio-venous (AV) fistula. Preferably, the fistula is created in the non-dominant forearm (Fig. 4) . An alternative is the use of the cephalic vein of the upper arm, but with a large vessel diameter there is a risk of a hyperdynamic shunt with the danger of cardiac stress.

The alternative to a native fistula is a plastic prosthetic shunt, e.g. in the form of a loop prosthesis on the forearm. It is important to note that the arm with a functioning dialysis shunt should only be used as a vascular access for dialysis; blood sampling or indwelling cannulae should be avoided.

Dietary aspects

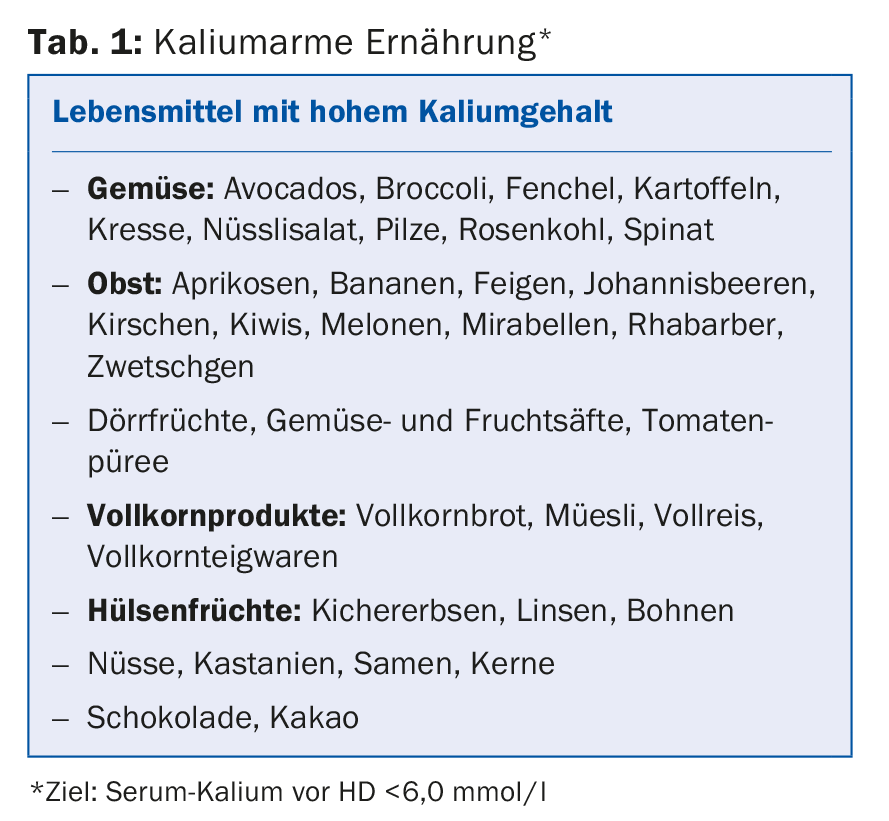

Dietary considerations must be taken into account in both PD and HD. As dialysis treatment progresses, residual function is expected to decline, and potassium, phosphate, salt, and fluid restriction become more important in parallel. For both procedures, the principle regarding fluid intake is: residual diuresis + 800 ml per day, saline intake 4-6 g per day. Especially in hemodialysis patients, nutritive potassium restriction is necessary (Tab. 1) as well as the use of cat ion exchangers (e.g. polysterol sulfonate, Resonium A). Caution should be used with drugs that increase serum potassium (ACE inhibitors, angiotensin II blockers), do not use spirolonactone and high-dose Bactrim.

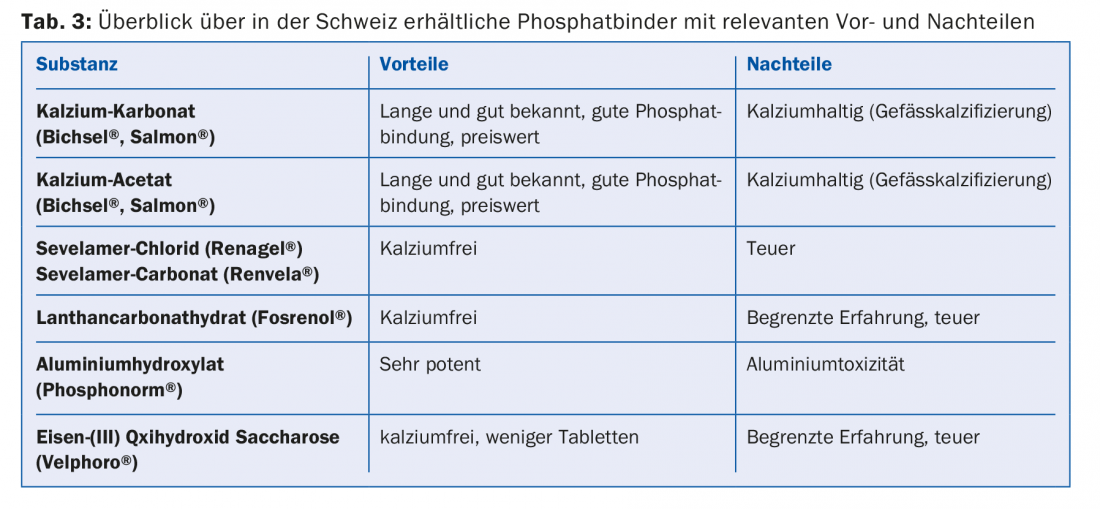

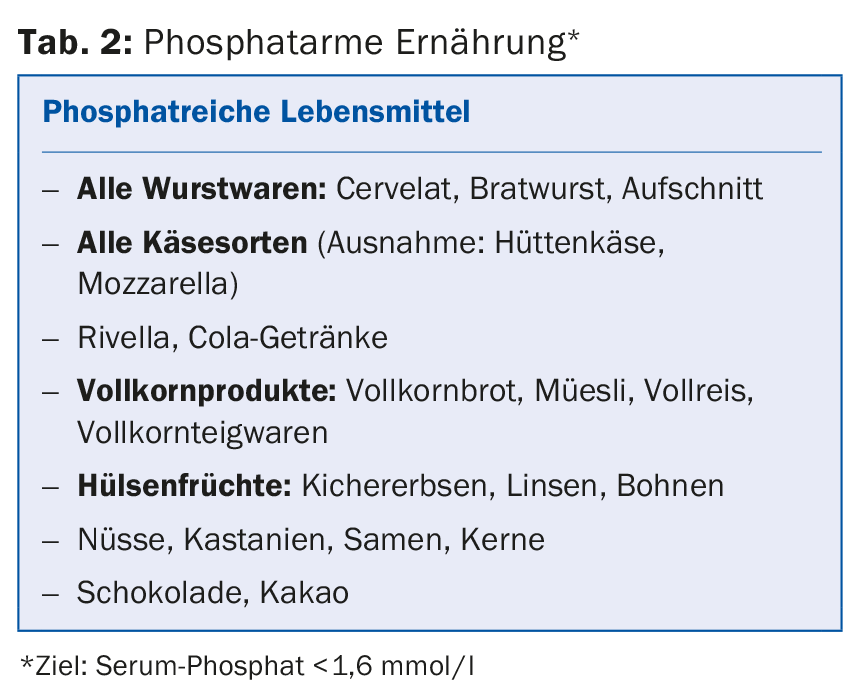

Another problem is hyperphosphatemia, since dialysis can eliminate only a portion of the reabsorbed phosphate. Persistent hyperphosphatemia is associated with increasing calcification of the vessels [9], so that long-term dialysis patients often suffer from generalized severe atherosclerosis. At the same time, hyperphosphatemia promotes renal secondary hyperparathyroidism [8]. For these reasons, on the one hand, a low-phosphate diet is necessary (phosphate-containing foods, Tab. 2) with simultaneous intake of phosphate binders. Among these, we distinguish between calcium-containing and calcium-free phosphate binders; these differ in potency of action, side effect profile, and interactions (Table 3).

Pharmacological aspects

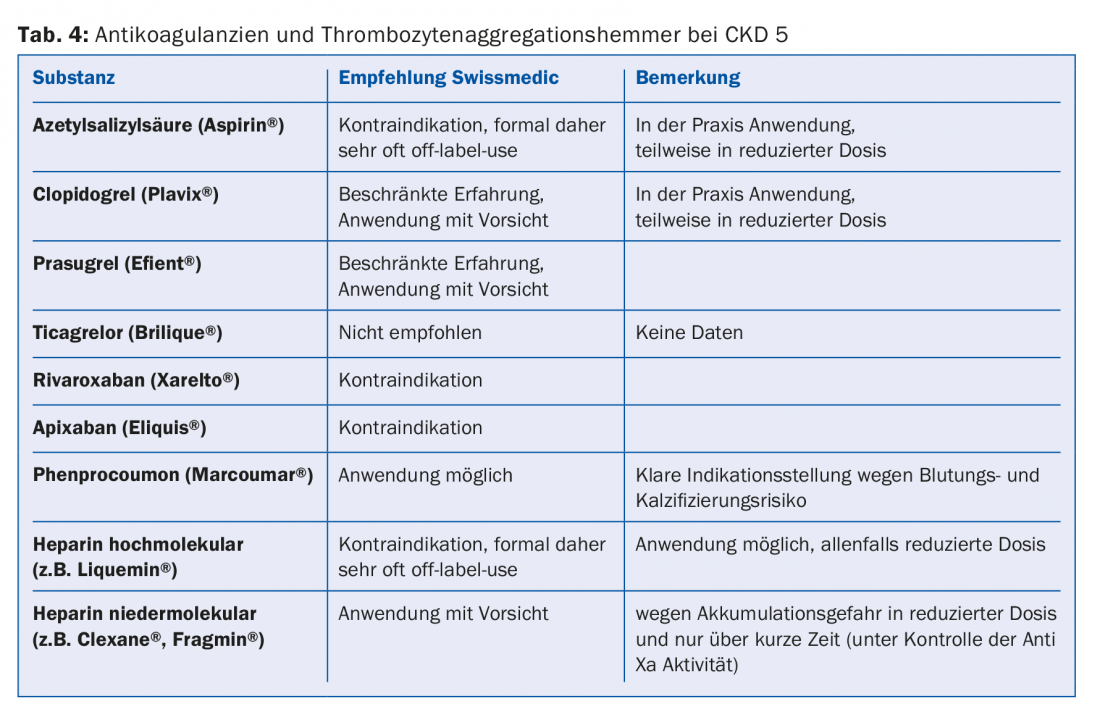

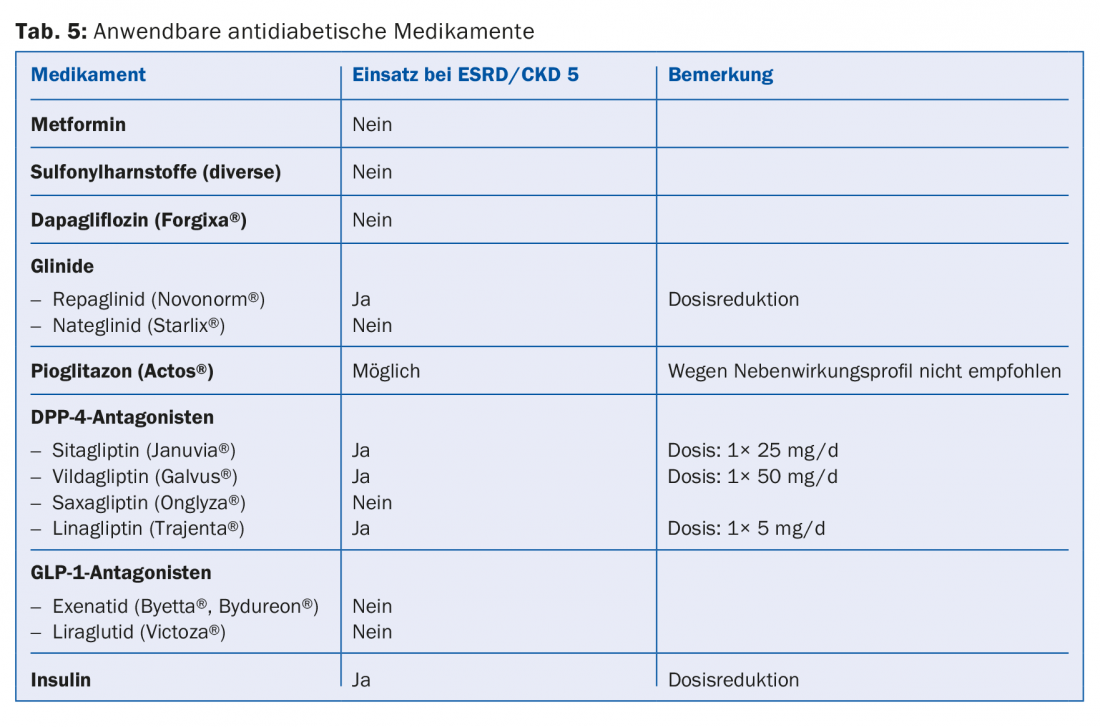

A large proportion of the drugs or their metabolites are eliminated renally. Therefore, absolute and relative contraindications should be adjusted according to the guidelines (e.g., Compendium). This is especially true for most antibiotics, anticoagulants and antiplatelet agents (Tab. 4). Since 30-40% of dialysis patients have diabetes, it is important to avoid certain antidiabetic drugs altogether (e.g. metformin, sulfonylureas) or to reduce the dose (e.g. sitagliptin, vildagliptin, etc.) (Tab. 5) [10]. Regarding pain medication, non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs should be administered only during a short period of time, if at all (risk of hyperkalemia, reduction of residual diuresis, additional platelet aggregation disorder). Paracetamol preparations (up to 3 g/day) and metamizole are considered relatively safe. Opiates should be taken in low doses, and here, too, accumulation of metabolites must be taken into account. Buprenorphine preparations or fentanyl are well suited in this regard (usually at a GFR <15 ml/min. Dose Halving [11]. Codeine preparations are less suitable (risk of accumulation and interaction potential). Similarly, tramadol should only be dosed low. Contraindicated is pethidine (risk of seizures).

Importance of care by family physicians

In hemodialysis patients who are seen three times a week, the nephrologist is often also the primary care physician. For patients who are further away from the dialysis center or who live in a nursing institution, the primary care physician still has a high priority. This is also true for CAPD patients who are only seen in the dialysis center every 1-2 months.

The family doctor is also important as a confidant when an elderly patient with a declining quality of life decides to discontinue dialysis treatment. Active dialysis discontinuation is responsible for nearly 20% of annual deaths in patients on renal replacement therapy. The family doctor, who has known the patient for years, is in a position to judge whether it is a life balance or at best a (treatable) depression. This should be addressed with medication before the important decision to discontinue dialysis treatment is made.

Literature:

- Swiss Association for Joint Tasks of Health Insurance (SVK): www.svk.org/assets/uploads.

- Elsässer H, et al: Planning a renal replacement procedure: what do you need to know? Schweiz Med Forum 2008; 8: 70-74.

- Kleophas W: When is the right time to start renal replacement therapy? Nephrologist 2012; 7: 96-103.

- Cooper BA, et al: A randomized, controlled trail of early versus late initiation of dialysis. N Engl J Med 2010; 363: 609-619.

- Kribben A, et al: Value, indications and limitations of peritoneal dialysis. Nephrologist 2007; 2: 74-81.

- KDOQI. Clinical practice guidelines for vascular access. Am J Kidney Dis 2006; 48: 176-247.

- Quick-Alert: “Misuse of dialysis catheters”; in progress (Patient Safety Switzerland).

- CKD-MBD Kidney disease Work Group: improving global outcomes (KDIGO). KDIGO clinical practice guideline for the diagnosis, evaluation, prevention, and treatment of chronic kidney disease-mineral and bone disorder (CKD-MBD), Kidney Int 2009; 76(Suppl): 1-130.

- Herzog CA, et al: Cardiovascular disease in chronic kidney disease. A clinical update form Kidney Disease; Improving Global Outcomes (KDIGO. Kidney Int 2011; 80: 572-586.

- Zanchi A, et al: Renal insufficiency and diabetes, anticipating. Switzerland Med Forum 2014; 14(6): 100-104.

- Liechti ME: Pharmacology of analgesics for practice, part 2: Opioids. Switzerland Med Forum 2014; 14: 460-464.

HAUSARZT PRAXIS 2016; 11(10): 32-38