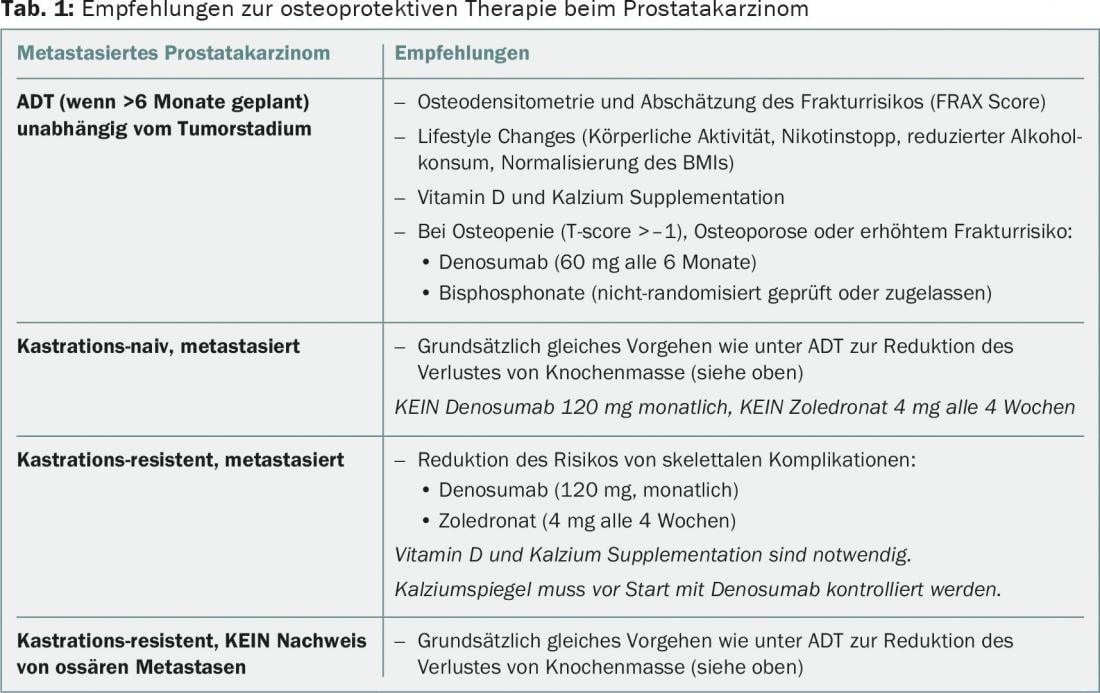

In men with advanced prostate cancer under androgen deprivation, osteodensitometry should be performed initially, and if osteopenia/osteoporosis, or increased fracture risk, is demonstrated, antiresorptive osteoporosis therapy should be considered. Bisphosphonates or denosumab are not indicated for the treatment of bone metastases in men with castration-naive metastatic prostate cancer and may lead to increased incidence of complications such as osteonecrosis of the jaw. The use of denosumab or zoledronate is reasonable in castration-resistant osseous metastatic prostate carcinoma with concomitant adequate supplementation of calcium and vitamin D.

Introduction

Advanced prostate cancer often occurs in older men. Drug treatments for metastatic prostate cancer, such as androgen deprivation therapy (ADT) with subsequent testosterone deficiency, as well as concomitant steroid administration during therapy with abiraterone, docetaxel, or cabazitaxel, have an unfavorable effect on bone density. This is all the more so because ADT is often carried out over a period of several years. The development of osteoporosis with corresponding complications must thus be taken into account. Furthermore, bone metastases occur in up to 90% of patients with metastatic prostate cancer. Skeletal events (SRE) such as pathologic fractures, spinal compression, radiotherapy, or orthopedic stabilization of osseous metastases, represent potential complications of skeletal metastases with high morbidity and significant costs; therefore, bone health should be attended to in men with advanced prostate cancer and bone-targeted therapy should be considered in a timely manner. As a distinctive feature of prostate cancer, the median survival with skeletal metastases from diagnosis is several years, which is why the use of antiresorptive therapies must be adapted to the individual disease situation. In the following, the various therapeutic options, as well as typical clinical situations, will be discussed.

Bisphosphonates and “Receptor Activator of NF-κ Ligand” (RANKL) inhibition.

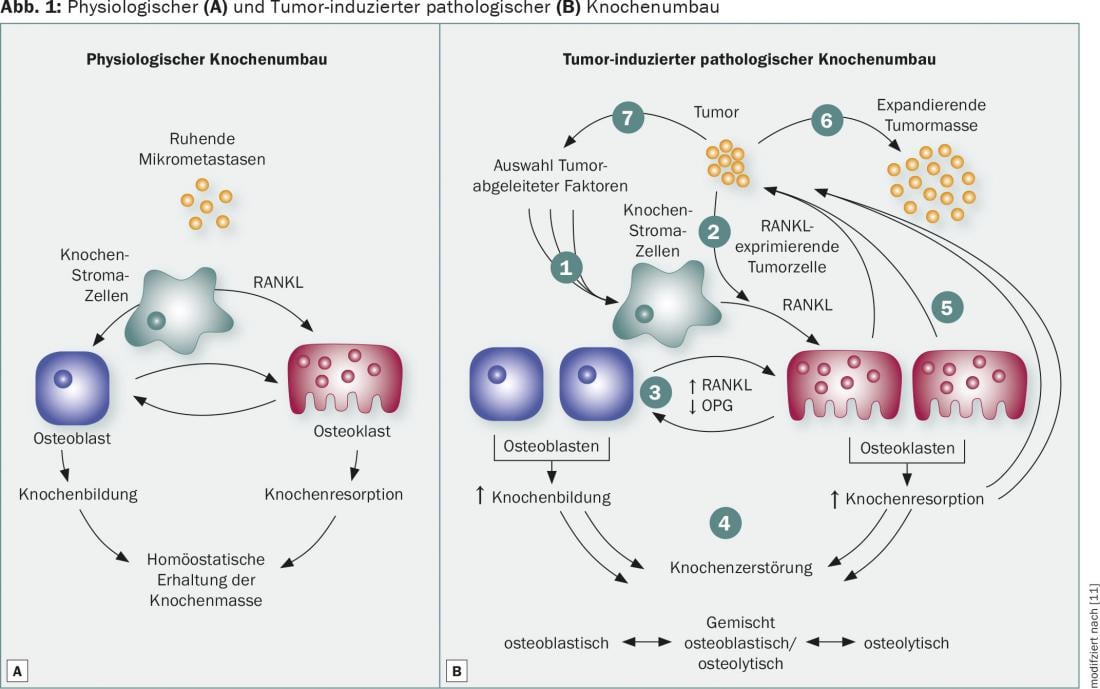

Bone remodeling is controlled by osteoblasts accumulating new bone substance and osteoclasts resorbing the inorganic and organic bone matrix. In physiological bone remodeling, the function of osteoblasts and osteoclasts is in equilibrium, which guarantees the maintenance of bone mass (Fig. 1A). The occurrence of bone metastases leads to increased osteoclast activity with subsequent increased bone resorption, which may be responsible for skeletal complications. The RANKL signaling pathway is a critical mechanism in osteoclast differentiation, activation, and survival that is overregulated in patients with osseous metastasis (Fig. 1B) . These findings led to the development of antiresorptive agents designed to inhibit osteoclast activity and thus prevent bone resorption. Bisphosphonates bind calcium to the bone surface and are phagocytosed by osteoclasts, leading to their apoptosis. The human monoclonal antibody denosumab binds RANKL with high affinity and specificity. Inhibition of interaction with RANK prevents bone resorption and cancer-related bone destruction by reducing the number and activity of osteoclasts.

Osteoporosis prophylaxis under androgen deprivation in prostate cancer.

Due to the blockade of testosterone synthesis, ADT leads to a reduction in bone density with a risk of developing osteoporosis. Therefore, at the beginning of a prolonged ADT (>6 months), osteodensitometry should be performed to determine bone density. In the presence of osteopenia, there is an increased risk of developing symptomatic osteoporosis – this progression should be prevented.

A phase 3 study, in men with prostate cancer treated with ADT who had either osteopenia (T-score <-1) or a history of osteoporotic fracture, showed a significant reduction in the incidence of vertebral fractures within the first two years on ADT when patients received osteoporosis prophylaxis with denosumab (60 mg every six months) [1].

Bisphosphonates have also been found to improve bone density in men on ADT, but no randomized trials can be found. Accordingly, denosumab or bisphosphonates should be considered in patients on ADT, with proven osteoporosis or increased risk of fracture (history of osteoporosis/osteoporotic fractures, bone densitometry with T-score <-1, sustained use of glucocorticoids), at the correct dosage and frequency for this indication (e.g., denosumab 60 mg every six months). Simultaneous lifestyle changes and sufficient supplementation of calcium and vitamin D are also recommended (Table 1).

Castration-naïve osseous metastatic prostate carcinoma.

In a randomized phase 3 study, the bisphosphonate zoledronate was evaluated at a monthly dose of 4 mg in patients with castration-naïve (these patients respond to therapy with ADT in 90% of cases) osseous metastatic prostate cancer [2]. A reduction in the risk of skeletal events, the primary endpoint of the study, and an improvement in overall survival were not demonstrated. Denosumab has not been tested in this indication. Based on this, bisphosphonates and RANKL inhibitors are not indicated in men with castration-naive osseous metastatic prostate cancer. The approval status of bisphosphonates and denosumab in Switzerland (“treatment of patients with bone metastases of solid tumors in combination with standard antineoplastic therapy”) unfortunately does not coincide with this study evidence, resulting in the risk of overtreatment of this patient group with increased risk of toxicity, in particular the occurrence of osteonecrosis of the jaw (ONJ) and (life-threatening) hypocalcemia. In contrast, as stated above, osteoporosis prophylaxis should of course also be considered in this group of patients.

Castration-resistant osseous metastatic prostate cancer.

In key studies by Saad et al. [3,4], zoledronate was shown to significantly reduce the risk of skeletal events compared with placebo, at a dose of 4 mg every three weeks for 15 to a maximum of 24 months in men with castration-resistant osseous metastatic prostate cancer. A follow-up study showed the superiority of denosumab (120 mg subcutaneously every four weeks) over zoledronate in this indication [5]. The median time to first skeletal event was prolonged by 3.5 months with denosumab versus zoledronate (20.7 vs. 17.1 months, HR 0.82, 95% CI 0.71-0.95, p=0.008). More grade ≥3 hypocalcemias occurred in the denosumab group (5 vs. 1%), ONJ were rare in both groups in the first two years (2 vs. 1%). However, it should be noted here that the incidence of ONJ increases significantly with several years of denosumab use, reaching up to 8% over the long-term. The use of denosumab or zoledronate is certainly reasonable in castration-resistant osseous metastatic prostate carcinoma with concomitant adequate supplementation of calcium and vitamin D. However, it should be noted that the recruitment of patients in these studies occurred before the era of the new antineoplastic agents abiraterone, enzalutamide, and radium. For all of these drugs, a significant reduction in skeletal events was observed in the trials that ultimately led to their approval [6–8].

The question of the optimal dosage and frequency of antiresorptive substances remains unresolved. In a randomized phase 3 trial, three-monthly dosing of zoledronate was noninferior to standard monthly dosing, in patients with metastatic carcinoma (including over 600 patients with prostate carcinoma), with respect to the primary endpoint of SRE [9]. A study by the Swiss Association for Clinical Cancer Research (SAKK 96/12 study, see www.sakk.ch) is currently evaluating standard dosing of denosumab against reduced frequency in men with castration-resistant osseous metastatic prostate cancer, particularly considering the increasing frequency of ONJ over the treatment period.

Castration-resistant prostate carcinoma without evidence of osseous metastases

Denosumab (120 mg every four weeks) has also been studied in men with prostate cancer with rising PSA under androgen deprivation but without the presence of metastases (so-called M0 CRPC patients) in a phase 3 study [10]. This showed a prolongation of bone metastasis-free survival, but without benefit for overall survival. The benefit was judged to be clinically irrelevant by both the regulatory authorities and the experts in the St. Gallen Advanced Prostate Cancer Consensus Conference (APCCC) in 2015 and is therefore generally not recommended. Denosumab is also not approved in any country for this indication.

Summary and outlook

Osteoprotective therapy represents an important treatment pillar in osseous metastatic prostate cancer in certain indications. Our recommendations are summarized in Table 1 . Overtherapy should be avoided, especially because of the risk of rare but serious side effects. Current studies will provide insight into dosing and treatment frequency of bisphosphonates and RANKL inhibitors over time. To date, there is no evidence that RANKL inhibitors in prostate cancer have an antineoplastic effect that is clinically relevant and results in improved survival. Thus, bisphosponates or denosumab should be used only as part of osteoporosis therapy, or to prevent SREs, in castration-refractory prostate cancer.

Literature:

- Smith MR, et al: Denosumab in Men Receiving Androgen-Deprivation Therapy for Prostate Cancer. NEJM 2009; 361(8): 745-755.

- Smith MR, et al: Randomized controlled trial of early zoledronic acid in men with castration-sensitive prostate cancer and bone metastases: results of CALGB 90202 (alliance). J Clin Oncol 2014; 32: 1143-1150.

- Saad F, et al: A randomized, placebo-controlled trial of zoledronic acid in patients with hormone-refractory metastatic prostate carcinoma. J Natl Cancer Inst 2002; 94: 1458-1468.

- Saad F, et al: Long-term efficacy of zoledronic acid for the prevention of skeletal complications in patients with metastatic hormone-refractory prostate cancer. J Natl Cancer Inst 2004; 96: 879-882.

- Fizazi K, et al: Denosumab versus zoledronic acid for treatment of bone metastases in men with castration-resistant prostate cancer: a randomised, double-blind study. Lancet 2011; 377: 813-822.

- Logothetis CJ, et al: Effect of abiraterone acetate and prednisone compared with placebo and prednisone on pain control and skeletalrelated events in patients with metastatic castration-resistant prostate cancer: exploratory analysis of data from the COU-AA-301 randomised trial. Lancet Oncol 2012; 13: 1210-1217.

- Fizazi K, et al: Effect of enzalutamide on time to first skeletal-related event, pain, and quality of life in men with castration-resistant prostate cancer: results from the randomised, phase 3 AFFIRM trial. Lancet Oncol 2014; 15: 1147-1156.

- Sartor O, et al: Effect of radium-223 dichloride on symptomatic skeletal events in patients with castration-resistant prostate cancer and bone metastases: results from a phase 3, double-blind randomised trial. Lancet Oncol 2014; 15: 738-746.

- Himelstein AL, et al. CALGB 70604 (Alliance): A Randomized Phase III Study of Standard Dosing vs. Longer Interval Dosing of Zoledronic Acid in Metastatic Cancer. ASCO Annual Meeting 2015. Abstract 9501.

- Smith MR, et al: Denosumab and bone-metastasis-free survival in men with castration-resistant prostate cancer: results of a phase 3, randomised, placebo-controlled trial. Lancet 2012; 379: 39-46.

- Dougall WC: Molecular pathways: osteoclast-dependent and osteoclast-independent roles of the RANKL/RANK/OPG pathway in tumorigenesis and metastasis. Clin Cancer Res 2012; 18(2): 326-335.

InFo ONCOLOGY & HEMATOLOGY 2016; 4(5): 8-12.