To do justice to patients with breakthrough pain, definition and delineation must be clear. The classification of breakthrough pain is reflected in a clear therapeutic concept. Rapid-onset opioids are a real asset in the treatment of breakthrough pain, but only if they are used correctly in the right patient – otherwise there is a risk of over- or under-therapy.

“Breakthrough pain: a transient exacerbation of pain that occurs either spontaneously or in relation to a specific predictable or unpredictable trigger despite relatively stable and adequately controlled background pain.”

Andrew N. Davies

Breakthrough pain has enormous importance in pain management, both for the patient and his or her family, and for the healthcare professionals caring for them. For the patient, breakthrough pain is unpredictable, especially if the trigger is unknown. The pain attacks make you afraid – afraid of the pain – and helpless. This, in turn, can wear down the patient. Breakthrough pain may also prevent the patient from moving, eating, or going to the bathroom. All this often leads to social withdrawal and reduces the quality of life. In addition, breakthrough pain carries the risk of self-therapy with uncontrolled medication use.

For relatives, breakthrough pain often triggers feelings of helplessness and anger: “No one can help!” – “Why doesn’t anyone help?”. This then occasionally leads to changing doctors or even frequent changes of doctors.

Breakthrough pain is often difficult for physicians to understand because they rarely witness the pain episodes. This can lead to uncertainty in assessing the pain, to the point of asking, “Is it really that bad?” Once the physician has recognized the scope of the pain, there follows the difficulty of classifying and thus treating breakthrough pain, which is often poorly understood.

Characteristics of breakthrough pain

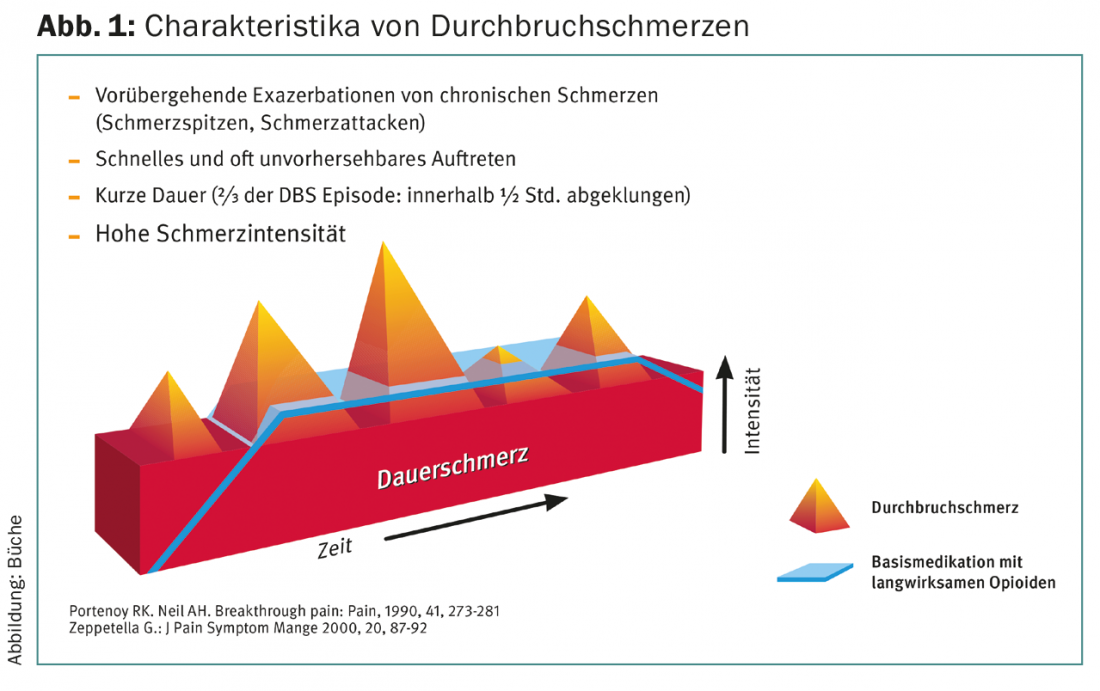

Synonyms for the term “breakthrough pain” are incisional pain or, in Anglo-Saxon usage, “breakthrough pain,” “incidental pain,” “intermittent pain,” or “episodic pain.” Characteristic of breakthrough pain is its temporal limitation, sudden onset, and severity. Typically, breakthrough pain lasts from a few minutes to rarely more than 60 minutes. One-third of breakthrough pain subsides in less than 15 minutes, and another third (two-thirds of all breakthrough pain overall) subsides within 30 minutes.

To be able to speak of breakthrough pain, the basic pain must be well controlled (Fig. 1) . Almost half of the patients have three or more pain attacks per day. Breakthrough pain is one of the difficult pains to treat.

Other forms of pain

Other pain conditions should be distinguished from breakthrough pain, in particular “end-of-dose” pain, an additional second pain, and pain exacerbation of a known pain. End-of-dose pain occurs when the dose interval of pain medication is chosen to be too long or when the usual dosing interval proves to be too long for a patient. For example, there are patients in whom MST Continus or Oxycontin work for a shorter time rather than the usual twelve hours. Similarly, there are patients in whom transdermal fentanyl does not work for the 72 hours hoped for. In these situations, the key is not to increase the dose or treat with a short-acting opioid, but to shorten the dosing interval.

Besides nociceptive pain due to growth and organ infiltration, there may also be nerve infiltration by the tumor. At best, the two different pains need to be addressed differently.

Also, progression of a tumor condition with an increase in pain should not be confused with breakthrough pain.

Classification of breakthrough pain and appropriate procedure

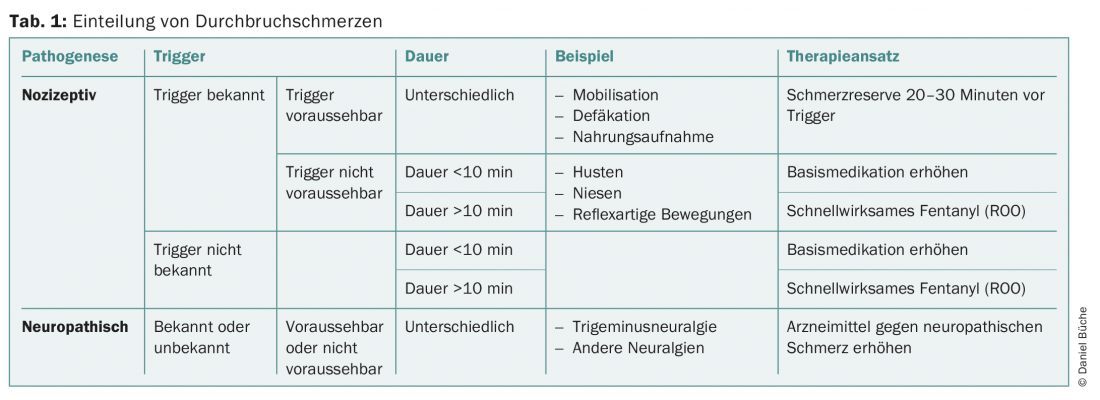

Breakthrough pain can have different causes. These range from osteoarthritis to fractures, inflammation to neuropathic pain. In order to be able to treat breakthrough pain adequately, a classification according to the pathogenesis, the trigger and the duration of the breakthrough pain has proven useful (Table 1).

If the breakthrough pain is neuropathic pain in the sense of trigeminal neuralgia or other neuralgia, neuropathic pain medications must be used. These are typically antiepileptic drugs (pregabalin, gabapentin, carbamazepine, and others), antidepressants (tricyclic antidepressants, duloxetine, venlafaxine, and others), or opioids.

If the breakthrough pain is a nociceptive pain and the trigger is known and predictable, taking a short-acting opioid (tramadol drops, Palexia, morphine drops, Oxynorm, Palladon, and others) about 30 minutes before mobilization, defecation, or food intake can prevent or at least relieve the breakthrough pain. If the trigger is known but not predictable, the question must be asked how long the pain is likely to last. If it can be assumed that the pain attack will be over after a few minutes, then any medication – incl. parenteral administration – too late or it will develop its main effect only when the breakthrough pain has already subsided. If the breakthrough pain lasts longer than 10-15 minutes, a fast-acting fentanyl can be used. If the pain is nociceptive with no known trigger, increase the base medication if the breakthrough pain is of short duration (<10 minutes); if it is of longer duration, try a fast-acting fentanyl. If this is successful, it can be continued; if it is not successful enough, the basic dose must be increased here as well.

Rapid-onset opioids

The ideal analgesic for breakthrough pain has the following characteristics: high analgesic potency, rapid onset of action, short duration of action, non-invasive application if possible, easy to use and well titratable, no adverse drug reactions, no metabolites, and a low potential for drug-drug interactions. Rapid-onset periods come closest to this ideal. They act very quickly and reach a high plasma concentration very quickly.

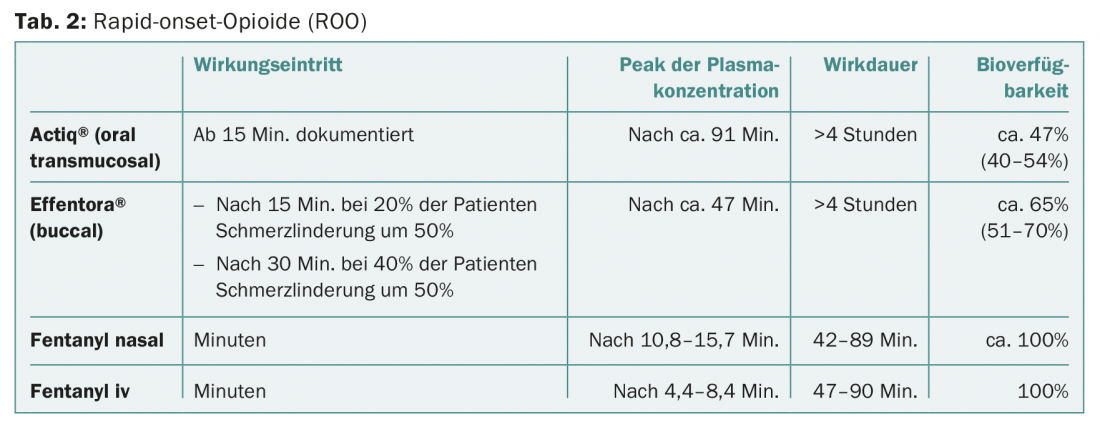

Rapid-onset opioids (ROO) are different galenic forms of fentanyl. This can be administered orally transmucosally (Actiq®), buccally (Effentora®), sublingually (Effentora®) and nasally, but nasal administration is not available in Switzerland (Tab. 2) .

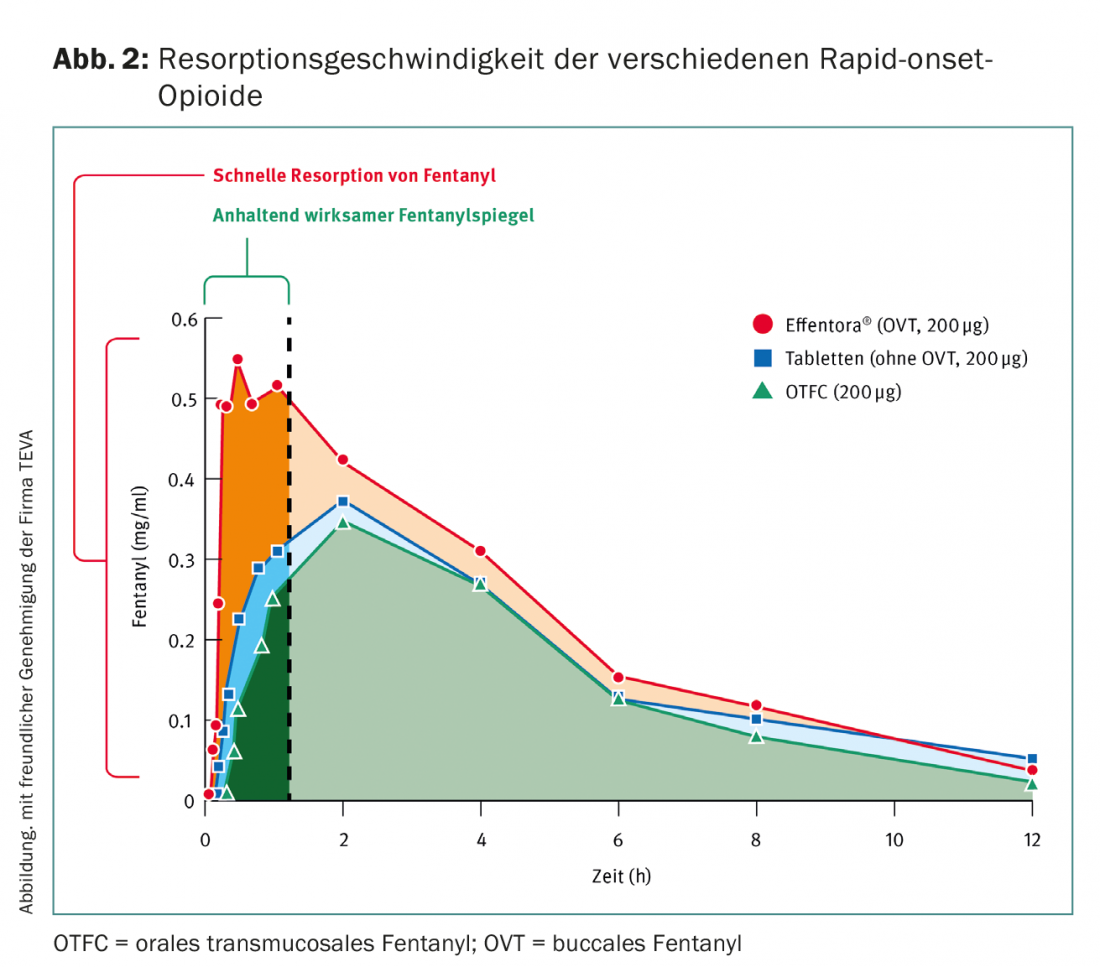

Here, buccal/sublingual fentanyl is preferable to oral transmucosal because it has a more rapid onset of action and reaches higher plasma concentrations more quickly (Fig. 2).

For the correct dosage, the information provided by Swissmedic should be followed. Importantly, the lowest dose of ROO should not be used until a baseline opioid dose of 60 mg morphine po, 25 µg/h transdermal fentanyl, or an equivalent dose of another opioid.

Further reading:

- Davies AN, et al: The management of cancer-related break-through pain: recommendations of a task group of the Science Committee of the Association for Palliative Medicine of GB and Ireland. Eur J Pain 2009: 13(4): 331-338.

- Deandrea S: Prevalence of undertreatment in cancer pain. A review of published literature. Ann Oncol 2008; 19: 1985-1991.

- Gomez-Batiste X, et al: Breakthrough cancer pain prevalence and characteristics in patients in Catalonia, Spain. J Pain Symtom Manage 2002; 24(1): 45-52.

InFo ONCOLOGY & HEMATOLOGY 2016; 4(3): 14-18.