Causes and backgrounds of behavioral addictions are diverse and should be seen and understood in the individual context. The motivation to change is often ambivalent and their insight into the disease is limited. The environment can support affected persons in accepting professional help. For both patients and their relatives, early recognition of behavioral addiction by specialists and a target-group-specific counseling program are of great benefit.

The term “behavioral addiction” is a relatively new term for a phenomenon that has been known for a long time: actually pleasant, rewarding behaviors such as gambling, Internet use (e.g., role-playing and action games or social networks), shopping, or sexual activities are pursued excessively. Control over the extent is lost, other important activities are neglected, and the excessively performed behavior serves more and more to regulate feelings and distract from other problem areas. An addiction-like problem eventually develops, with no psychotropic substance being externally supplied. The psychotropic effect is produced by the body’s own biochemical changes. Neural circuitry and neurotransmitter availability, particularly in the dopaminergic reward system, change [1,2].

However, the diagnostic classification of such pathological behaviors as addiction or dependence is scientifically controversial. In the current International Statistical Classification of Diseases (ICD-10), they are classified in the section “abnormal habits and disorders of impulse control,” although only “pathological gambling” is explicitly listed there as a disorder.

In the new edition of the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM 5), however, gambling disorder is listed in the chapter on substance-related and addictive disorders. Other forms of behavioral addiction are not specified as disorders, as in ICD-10, and are most likely to be classified as impulse control disorders. Only internet gaming disorder is mentioned in chapter three of DSM 5 as a disorder for which further research is needed before it can be considered as a formal diagnosis.

It remains to be seen how the problem of classification will be solved in the future and how the associated definition of diagnostic criteria and assignment will be made in ICD-11.

Individual explanatory model

Much more relevant for practice than this long-standing debate about the correct classification is the individual diagnosis, i.e., the exploration and attention to the possible causative and maintaining conditions for the excessive behavior and for the (often existing) further problem areas as well as comorbid disorders. This shows that behavioral addiction is a very heterogeneous disorder. Not only is the nature of the behavior different, but so is the background for the excessive derailment of behavior that is not harmful in itself. For example, behavioral addictions enable some sufferers to cope with stressful experiences or unpleasant emotional states. Others need the addictions as an outlet for permanent stress and unresolved problems or use them to compensate for feelings of inferiority. Not infrequently, interpersonal conflicts also play an important role.

Over time, a habituation effect can occur, which is associated with the neurobiological changes mentioned above. Social sequelae also occur and preexisting psychosocial problems are exacerbated. In this way, a self-reinforcing psychological-biological-social vicious cycle of behavioral addiction occurs [3]. Understanding this individually and discussing it with the patient is as crucial to the success of counseling – often conducted primarily by the primary care physician – and to fostering motivation to change as it is to planning and implementing specific therapy.

Motivation for change

Due to the often ambivalent motivation of behaviorally addicted people for therapy and change, support in this area plays a central role: How is it to be understood that the person affected does not reduce his behavior, although he is well aware of the negative consequences? Why is questioning these behaviors often experienced as self-esteem threatening and therefore not allowed? A discussion of the issue of whether the person concerned is “addicted” or not usually leads nowhere. Abstinence is also usually not a motivating goal of therapy. Instead, the described development of an individual explanatory model together with the patient (and if possible also the relatives) is crucial for successfully strengthening the motivation to change.

It is also recommended to explore to what extent the excessive behavior serves to cope with or distract from negative sensitivities or rather to search for the “kick”, i.e. to achieve positive sensitivities. Likewise, the classification of the respective disturbance pattern on an axis between impulsive (risk seeking, lack of control) and compulsive (risk avoidance, overcontrol) behaviors can be helpful for setting change goals and the corresponding therapeutic approach [4].

Therapy for Internet and gambling addiction

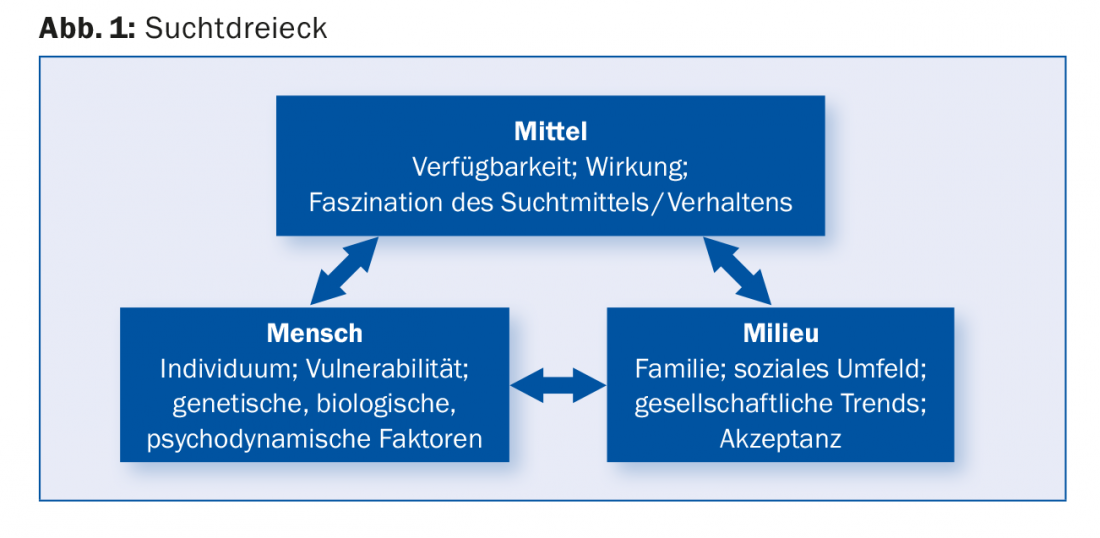

In practice, Kielholz and Ladewig’s addiction triangle, which is often cited for substance-related addictions, is suitable for the therapy of behavioral addictions (Fig. 1). In this triangle, the substance, the person and the environment influence each other.

Access to addictive behavior, corresponding to the addictive substance in substance-related addictions, is an important factor for treatment. Limiting this access or raising the threshold for access is beneficial for treatment in the outpatient setting in many cases. At least partial abstinence, e.g. from individual applications on the Internet, improves the chances of therapeutically relevant changes. Media availability, especially through mobile devices such as smartphones, poses a major challenge in this regard. Offers such as online games, social media, sports betting or online casinos can be used in a low-threshold and unobtrusive way. This makes (self-)control more difficult, especially if there is an impulse control problem, which is often the case not only with addicts but generally in adolescence due to neurobiological development.

The “milieu”, i.e. the personal environment and thus also the relatives, represents both a risk factor and an important resource. As mentioned above, in the case of addictive disorders, the motivation of the persons affected to change is often ambivalent and their insight into the disease is limited. The environment can support affected persons in accepting professional help. Changes related to addiction are noticed early on by those around them, such as internal absence and withdrawal from social and family activities. Counseling of relatives, e.g., by family doctors, who as confidants are often the first point of contact, creates good conditions for parents and partners to become active and, with a certain amount of pressure, motivate affected persons to accept specific professional help.

Therapeutic interventions for adolescent gamers.

To date, no clear evidence-based treatment recommendations can be made for Internet addiction [5]. However, practice shows that cognitive-behavioral interventions as well as multimodal therapy approaches involving relatives often bring success [2].

Mostly parents of teenagers or young men who play online games excessively on computers, game consoles or smartphones come forward. Performance at school or work declines and sufferers withdraw from social activities. Persistent quarrels and escalating family conflicts push parents to the limits of their patience and put a strain on their self-esteem as parenting leaders. They feel overwhelmed in the face of the seemingly hopeless situation and are therefore usually highly motivated for change. This willingness of parents to seek help is an essential resource. A favorable starting position exists in particular if the parents can speak openly about their concerns and at the same time represent the need for treatment to the adolescent and also enforce it. This is already a first signal for the restoration of the often displaced hierarchy.

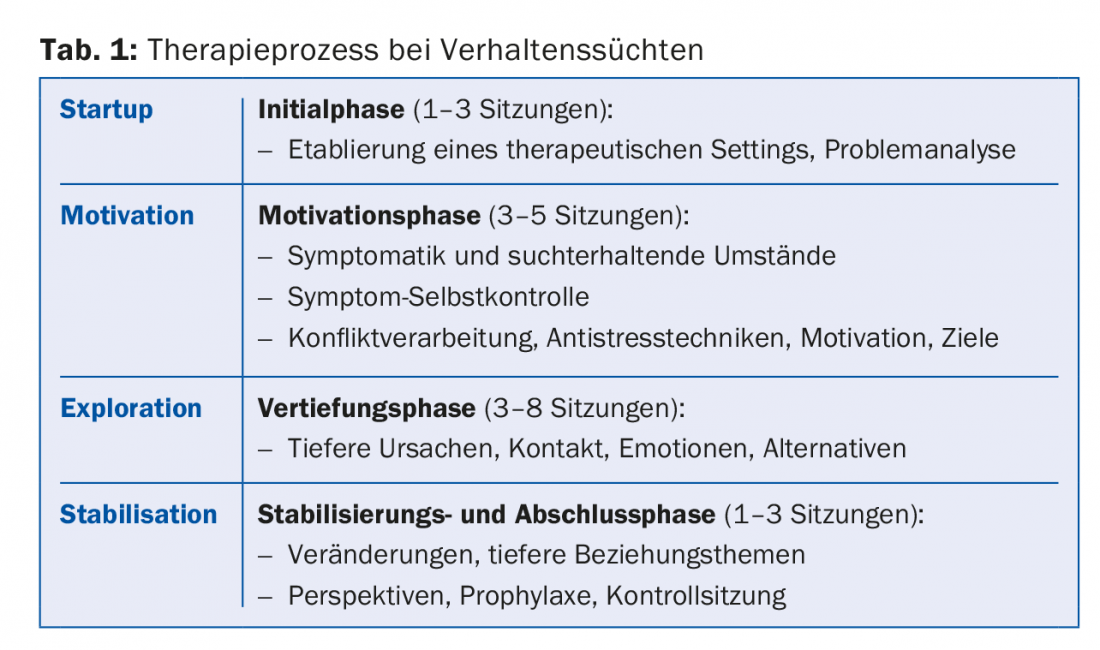

In many cases, only joint sessions with parents or the whole family allow adolescents to engage in a longer-term therapeutic process. The interventions that are helpful in this context are shown in a publication based on many years of practical experience and in the ideal-typical sequence of the therapy process shown in table 1 [6].

Gambling addiction: experiences from outpatient practice

The main problem in gambling addiction therapy is reaching those affected in the first place. Only 5% of excessive and pathological gamblers seek treatment services [7]. In addition, only about 50% of the counselors have experience with this topic, so that most of the people affected point out the problem themselves before it is recognized by a professional [8]. In this context, raising awareness among primary care physicians would also be desirable.

What is the experience at the Center for Gambling Addiction and Other Behavioral Addictions in Zurich (RADIX Kooperation Sucht), which opened in 2011? A search showed that in the canton of Zurich, before 2011, only two dozen cases on the subject were registered with the relevant specialist institutions. With the service geared to the target group, a continuous increase in inquiries has been observed since the opening, so that currently over 130 active gambling addiction cases are being treated. Experience has shown that a target group-specific offer makes it easier to seek professional help. Generally, a gambling history is taken in an initial assessment, and the personal and family situation is discussed. The combined offer of group and individual resp. Couples therapy is said to be helpful by those affected.

Relapses are to be expected

Group therapy, in particular, allows pathological gamblers to talk openly about their behavior and express their feelings of guilt and shame. Here, expected relapses can and should be worked through and positive steps can be appreciated together. Experience shows that failure to keep session appointments or dropping out of therapy are basically predictors of further relapse. Regular use of therapy services and regular completion of treatment, including follow-up sessions, are important to establish a good prognostic basis for future development.

Literature:

- Grüsser SM, Thalemann CN: Behavioral addiction. Diagnostics, Therapy, Research. Huber: Bern 2006.

- Bilke-Hentsch O, Wölfling K, Batra A: Praxisbuch Verhaltenssucht. Thieme: Stuttgart 2014.

- Rufer M: Motivation to change in behavioral addictions. Bulletin Prevention and Health Promotion in the Canton of Zurich 2011; 29: 9-10.

- Rufer M, Martin Sölch C: Cognitive behavioral therapy of computer game addiction. AddictionMagazine 2011; 3: 30-33.

- Batthyany D, Pritz A: Intoxication without drugs. Springer: Vienna 2009.

- Eidenbenz F: Systemic therapy for internet addiction – phase model. Addiction Therapy 2015; 16: 179-186.

- Eidgenössische Spielbankenkommission ESBK (ed.): Glücksspiel: Verhalten und Problematik in der Schweiz. 2009

- Lischer S, et al: Raising awareness of gambling addiction-specific problems among professionals in the external care system. Addiction 2014; 60(5): 289-296.

HAUSARZT PRAXIS 2016; 11(5): 30-33