Psoriasis vulgaris or plaque psoriasis is the most common clinical manifestation of psoriasis. Guttate psoriasis often occurs in adolescents and presents with the appearance of plaques up to the size of a lentil, red and slightly scaly. The psoriatic erythroderma and the generalized pustular psoriasis of Zumbusch represent the maximum variants of psoriasis (entire integument strongly reddened and covered with easily detached scales or covered with pin-sized and often confluent pustules). Psoriasis inversa is found in the intertriginous spaces, axillae, inguinal and perianal (sharply demarcated, reddish, moist shiny macules from which the scales have detached due to the warm and humid microclimate). Psoriatic nail infestation occurs in up to 50% of patients. Psoriasis also affects the joints in up to 20% of cases (psoriatic arthritis). It manifests with pain and swelling, most commonly in the finger and knee joints, but also in the axial skeleton.

Psoriasis, also known as psoriasis, is a skin disease characterized externally by sharply demarcated red plaques due to inflammatory skin infiltration and firmly adherent silvery-white scaling due to epidermal hyperproliferation and parakeratosis. Psoriasis is a primary, autoimmune and genetic, keratinocyte- and T-cell-mediated systemic disease with inflammatory manifestations on the skin, nails and joints (psoriatic arthritis) and a number of comorbidities. Accordingly, therapeutic approaches are anti-inflammatory, anti-proliferative and keratolytic. They are based on the severity of the disease, related to the area extent and individual efflorescence (PASI), on the impairment of quality of life (DLQI) and special localizations (psoriasis inversa, palmoplantar psoriasis, nail psoriasis) as well as on patient age and comorbidities (arthritis, metabolic syndrome, cardiovascular diseases, autoimmunity, depression, suicidality). In 80% of cases, there is mild psoriasis that can be adequately controlled with external treatment (corticosteroids, vitamin D analogues) and phototherapy (PUVA, UVBnb). However, 20% require classical systemic therapy (methotrexate, ciclosporin, acitretin) or therapy with biologics and targeted molecules due to the extent or severity of the disease. Especially in the severe forms of psoriasis, psychological distress, comorbidities, and medical economic considerations must be factored into the individual treatment plan.

Epidemiology and pathophysiology

Psoriasis has a prevalence of 2-3% of the population and is one of the most common and important dermatological diseases of all. It can occur at any age and without gender preference, although the initial manifestation has two peaks of frequency: about two-thirds of all patients suffer from type I psoriasis with an onset of disease before the age of 40 and a peak between the ages of 16 and 21. The course is often severe and extensive, the family history is usually positive, and there is an association with HLA-Cw6 [1]. The more chronic static plaque type II psoriasis starts after the age of 40, is sporadic and associated with HLA-Cw2 [2].

Within psoriatic plaques, there is up to fourfold accelerated hyperproliferation of the epidermis, secondary to an inflammatory response. The keratinocytes can release DNA-binding antimicrobial peptides upon irritation of any kind. As a peptide-DNA complex, these cause a pronounced interferon-α release [3], which is considered one of the most important factors for T cell activation [4]. Activated Th-1 and Th-17 type T lymphocytes then infiltrate the skin and release proinflammatory cytokines such as tumor necrosis factor(TNF)-α, interleukin(IL)-17 and IL-23.

Clinical manifestations of psoriasis

The typical skin change is the psoriatic plaque, which shows three characteristic phenomena that also have diagnostic relevance: First, mechanical removal of the scales with e.g. a wooden spatula reveals silvery-white (parakeratotic) scale material as “candle wax phenomenon”, second, one can remove the deeper cell layers down to the so-called “last cuticle”, and third, further scratching reveals punctiform bleeding from the opened giant capillaries in the dermal papillae tips as Auspitz phenomenon or “bleeding dew phenomenon”.

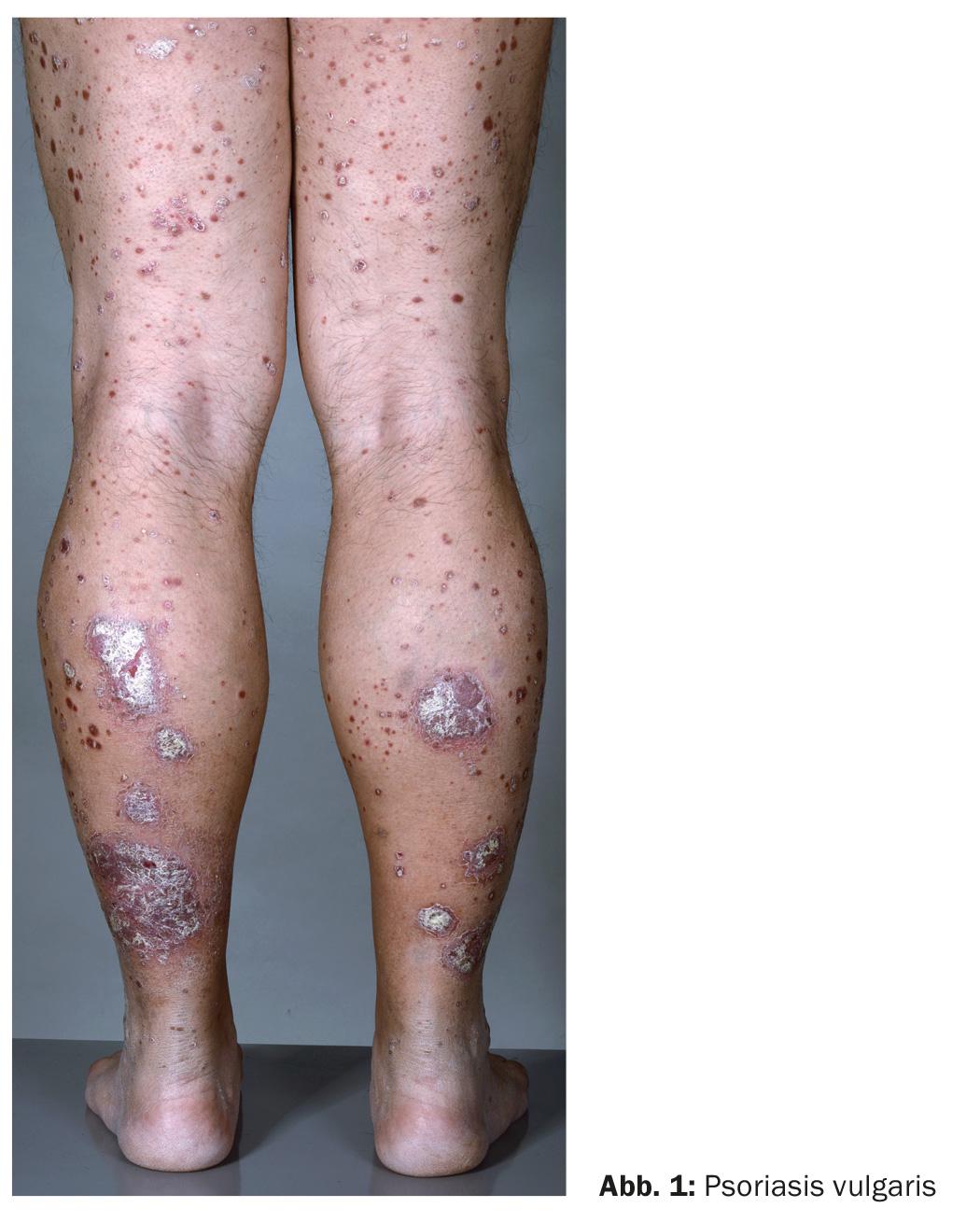

Psoriasis vulgaris (Fig. 1): Psoriasis vulgaris or plaque-form psoriasis is the most common clinical manifestation of psoriasis. It manifests with the characteristic sharply demarcated, reddish, infiltrated and scaly plaques on the elbows, kneecaps and scalp under the hair, but also on the coccyx, knuckles and under the earlobes. In general, according to a mechanical provocability of psoriatic efflorescence (isomorphic stimulus effect or Köbner phenomenon), skin areas are affected that are often strained, such as the mentioned joints and the shins, or that are otherwise mechanically stressed, e.g. under the belt. The foci vary in size, and in cases of extensive infestation, they may be arranged in a ring with central healing or confluent in a garland shape.

Psoriasis guttata (Fig. 2): Guttate psoriasis often occurs in adolescents and presents with the appearance of plaques up to the size of a lentil, red and slightly scaly. A tonsillar or perianal streptococcal infection is often the triggering factor. Their superantigens can cause T-cell activation, whereupon an immune response against endogenous keratin is initiated with the bacterial M-protein [5].

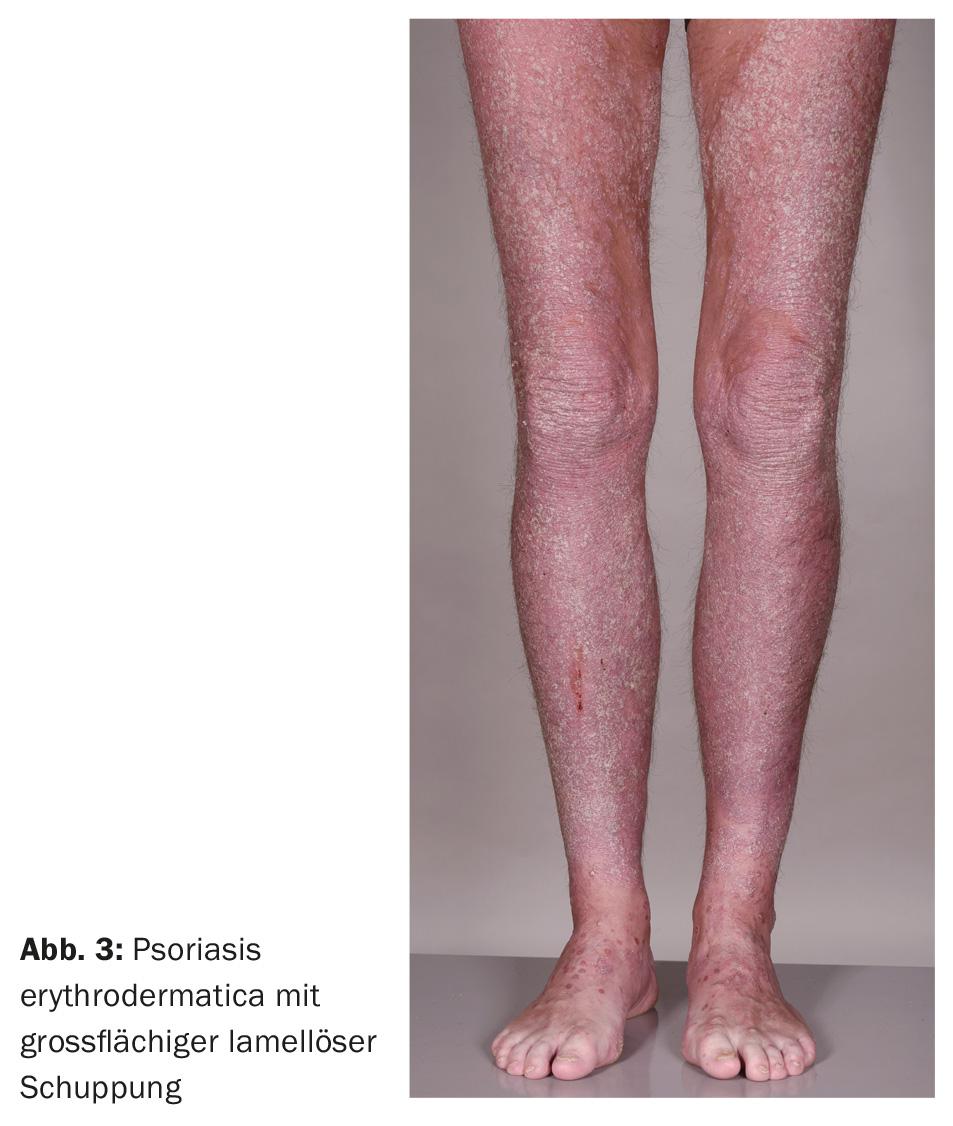

Psoriatic erythroderma: Psoriatic erythroderma (Fig. 3) and generalized pustular psoriasis of Zumbusch (Fig. 4) represent the most severe, sometimes life-threatening maximum variants of psoriasis. The entire integument is strongly reddened and covered with easily detached scales or covered with pin-sized and often confluent pustules. Laboratory signs of inflammation are found, often with marked leukocytosis. Recently, the IL36RN gene has been identified as the site of mutations that can trigger pustular psoriasis [6–9].

Psoriasis in particular localizations: Psoriasis inversa is found in the intertriginous spaces, axillae, inguinal and perianal. The skin findings are characterized as sharply demarcated, reddish, moist shiny macules from which the scales have detached due to the warm and humid microclimate. Local factors such as maceration, bacterial or mycotic infections may provoke or aggravate psoriasis in these locations.

Psoriatic nail infestation (Fig. 5) occurs in up to 50% of patients and is associated with psoriatic arthritis in 85% of cases, thus has a marker function. 93% of patients feel cosmetically affected by nail infestation [10].

Psoriatic arthritis: Psoriasis also affects the joints in up to 20% of cases [11]. Psoriatic arthritis manifests with pain and swelling, most commonly in the finger and knee joints, but also in the axial skeleton. In most cases, psoriatic skin lesions precede joint involvement. Before joint involvement can be objectified, enthesitis, i.e. inflammation of the tendon attachment sites, may also occur. A striking feature is a high association between psoriatic arthritis and nail changes, which thus assume a marker function for the risk of the joint disease.

Severity

Psoriasis is considered severe when it reaches ten points in one of three scores [12]: PASI (Psoriasis Area and Severity Index), BSA (Body Surface Area) and DLQI (Dermatology Life Quality Index). The most important score is the PASI, which measures erythema, infiltration, scaling, and surface extent at the appropriate sites. A formula yields a score from 0 to 72, with a result of >10 considered severe psoriasis. Affected body surface area of 10% or more and a DLQI of ten points or more also indicate severe psoriasis (“rule of 10’s” [12]), with the DLQI being particularly prominent in nail and inverse psoriasis.

Comorbidities

Two hundred years after the separation of dermatology from internal medicine in the era of Alibert (1768-1837) and Wilson (1809-1894), psoriasis is again considered a systemic disease. Recently, a database of anonymized long-term data from primary care physicians showed that major cardiovascular risk factors are clustered in patients with psoriasis [13]. Patients with severe psoriasis were affected more frequently than those with mild psoriasis: 20.7% of patients with severe psoriasis suffered from obesity, compared with 13.2% in the control group. 30.1% were smokers (control group 21.3%), 20% had hypertension (control group 11.9%), 7.1% had diabetes mellitus (control group 3.3%), and 6% had hyperlipidemia (control group 3.3%). All of these conditions put patients in a high-risk category for early cardiovascular mortality. The risk of having a heart attack is increased threefold for a 30-year-old severe psoriatic, and by half for a 60-year-old. Furthermore, it is discussed whether, in addition to the cardiovascular risk factors mentioned above, chronic systemic inflammation in psoriasis does not also promote arterio- and coronary sclerosis. After all, one fifth of all psoriatic patients suffer from psoriatic arthritis, which is also associated with significant pain and mobility restrictions in more than half. These results show us once again that psoriasis is a serious disease with a number of associated comorbidities [14].

Literature:

- Christophers E, Mrowietz U, Sterry W: Psoriasis. 2nd ed. Berlin: Blackwell 2003.

- Henseler T: The genetics of psoriasis. J Am Acad Dermatol 1997; 37: S1-11.

- Lande R, et al: Plasmacytoid dendritic cells sense self-DNA coupled with antimicrobial peptide. Nature 2007; 449: 564-569.

- Nestle FO, et al: Plasmacytoid predendritic cells initiate psoriasis through interferon-alpha production. J Exp Med 2005; 202: 135-143.

- Rasmussen JE: The relationship between infection with group A beta hemolytic streptococci and the development of psoriasis. Pediatr Infect Dis J 2000; 19: 153-154.

- Hussain S, et al: IL36RN mutations define a severe autoinflammatory phenotype of generalized pustular psoriasis. J Allergy Clin Immunol 2015; 135: 1067-1070.e9.

- Navarini AA, et al: Homozygous missense mutation in IL36RN in generalized pustular dermatosis with intraoral involvement compatible with both AGEP and generalized pustular psoriasis. JAMA Dermatol 2015; 151: 452-453.

- Navarini AA, et al: Rare variations in IL36RN in severe adverse drug reactions manifesting as acute generalized exanthematous pustulosis. J Invest Dermatol 2013; 133: 1904-1907.

- Setta-Kaffetzi N, et al: Rare pathogenic variants in IL36RN underlie a spectrum of psoriasis-associated pustular phenotypes. J Invest Dermatol 2013; 133: 1366-1369.

- de Jong EM, et al: Psoriasis of the nails associated with disability in a large number of patients: results of a recent interview with 1,728 patients. Dermatology 1996; 193: 300-303.

- Reich K, et al: Epidemiology and clinical pattern of psoriatic arthritis in Germany: a prospective interdisciplinary epidemiological study of 1511 patients with plaque-type psoriasis. Br J Dermatol 2009; 160(5): 1040-1047.

- Finlay AY: Current severe psoriasis and the rule of tens. Br J Dermatol 2005; 152: 861-867.

- Neimann AL, et al: Prevalence of cardiovascular risk factors in patients with psoriasis. J Am Acad Dermatol 2006; 55: 829-835.

- Katsambas A: Treating psoriasis as a chronic inflammatory systemic disease. Br J Dermatol 2008; 159(Suppl 2): 1.

DERMATOLOGIE PRAXIS 2016; 26(2): 6-9