The results of the SPRINT study – lower mortality with more intensive hypertension treatment – were the focus of interest at the 11th Hypertension Day. As one speaker put it, “The SPRINT study has hit us in the gut.” However, it is not yet clear whether the blood pressure target values will be set lower again, because this would suddenly turn a large part of the population into hypertension patients. There was agreement that blood pressure measurement needs to be improved; means for this are 24-hour measurement, home measurement and optimized techniques.

In his presentation, Prof. Frank Ruschitzka, MD, University Hospital Zurich, discussed the SPRINT study, which was published in November 2015 and calls into question the currently valid treatment guidelines [1]. 9300 individuals with blood pressure above 130 mmHg and increased cardiovascular risk, but without diabetes, were randomized into two groups: Intensively treated patients were targeted to have a systolic blood pressure (SBD) below 120 mmHg, and standard therapy patients were targeted to have an SBD below 140 mmHg. After one year, the mean SBD in the intensive therapy group was 121.4 mmHg, and in the standard therapy group it was 136.2 mmHg. After a median follow-up of 3.2 years, the study was terminated early because significantly fewer cardiovascular events occurred in the intensive therapy group (1.65% vs. 2.19% per year). All-cause mortality was also significantly lower in patients receiving intensive therapy (hazard ratio 0.73). Side effects such as hypotension, syncope, electrolyte disturbances, and acute renal failure were more common in the intensive treatment group, but falls were equally common as in the standard treatment group.

“But don’t ask me what the target blood pressure values are now,” Prof. Ruschitzka said. “At the moment, no one knows.” The results of the SPRINT study will certainly be a topic of conversation the next time blood pressure targets are discussed. There is no cost-benefit analysis yet. If the blood pressure target values of the SPRINT study were defined as general target values, a large part of the population would be hypertensive patients (in need of treatment) at one stroke. It should also be noted that in the SPRINT study, blood pressure was measured differently than is possible under everyday conditions: the study participants measured blood pressure themselves in an isolated room, without the presence of a healthcare professional.

Modern techniques enable more precise blood pressure measurement

Blood pressure values are always given in absolute numbers. People often forget that blood pressure is highly variable – both short-term (within minutes) and long-term (over weeks, months or seasons). However, a high variability of blood pressure is dangerous, explained Prof. Gianfranco Parati, Milano (Italy): Individuals with highly variable blood pressure have a significantly increased risk of organ damage, such as stroke or cardiovascular events. The same applies to people whose blood pressure does not drop during the night (“non-dippers”). To eliminate diurnal variability as much as possible, medications should be prescribed in such a way that, on the one hand, they do not act for only a few hours and, on the other hand, they are adapted to the patient’s personal situation (e.g., in the case of “non-dippers” taking the antihypertensive in the evening).

To avoid errors in blood pressure measurement (Table 1) and to determine the variability of blood pressure in general, it is difficult to avoid 24-hour blood pressure measurement and ambulatory measurements. “Measurements in practice show only the tip of the iceberg,” Prof. Parati reminded us.

Close blood pressure monitoring in patients receiving therapy is not difficult to achieve, as many self-monitor regularly anyway. However, it is important that these controls are performed properly. New techniques and methods, such as telemonitoring, graphical display and automatic storage of measured values, help to improve patient compliance. The speaker also introduced a new cuff (“IntelliWrap”) that has a 30% larger contact zone and is designed to provide correct blood pressure readings regardless of positioning on the arm.

Therapy-resistant hypertension – how to clarify?

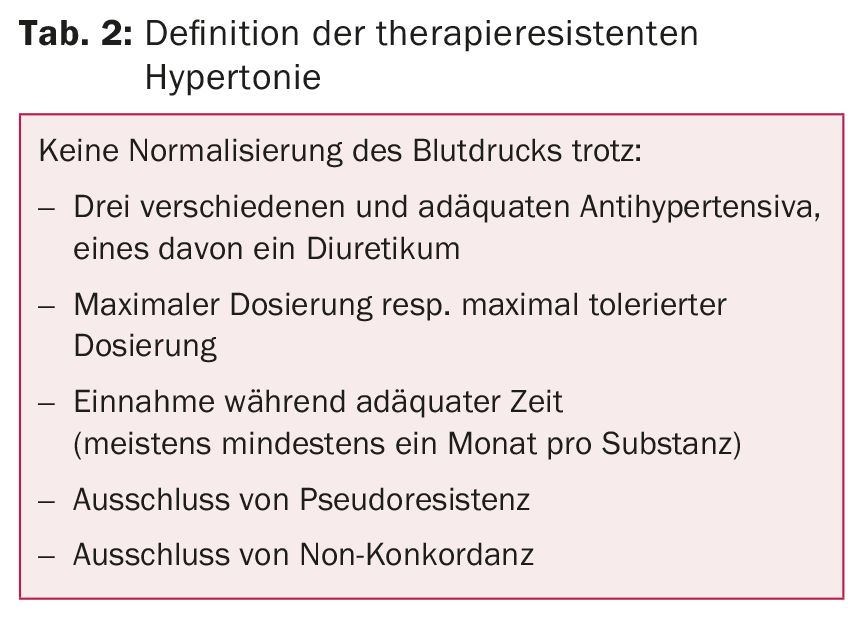

Several studies have shown that a single measurement of SBD in the office or hospital with values between 120 and 157 mmHg is not suitable to diagnose controlled or excessive blood pressure with sufficient certainty [2,3]. “So physicians are not very good at diagnosing hypertension in their practice,” emphasized Prof. Edouard Battegay, MD, University Hospital Zurich. “For this reason, 24-hour measurement is the gold standard.” The most reliable results come from a combination of office, home and 24-hour measurement. This is particularly true in patients with supposedly refractory hypertension (tab. 2) : If a 24-hour measurement is performed, the blood pressure proves to be normal in one third of the “therapy-resistant” patients.

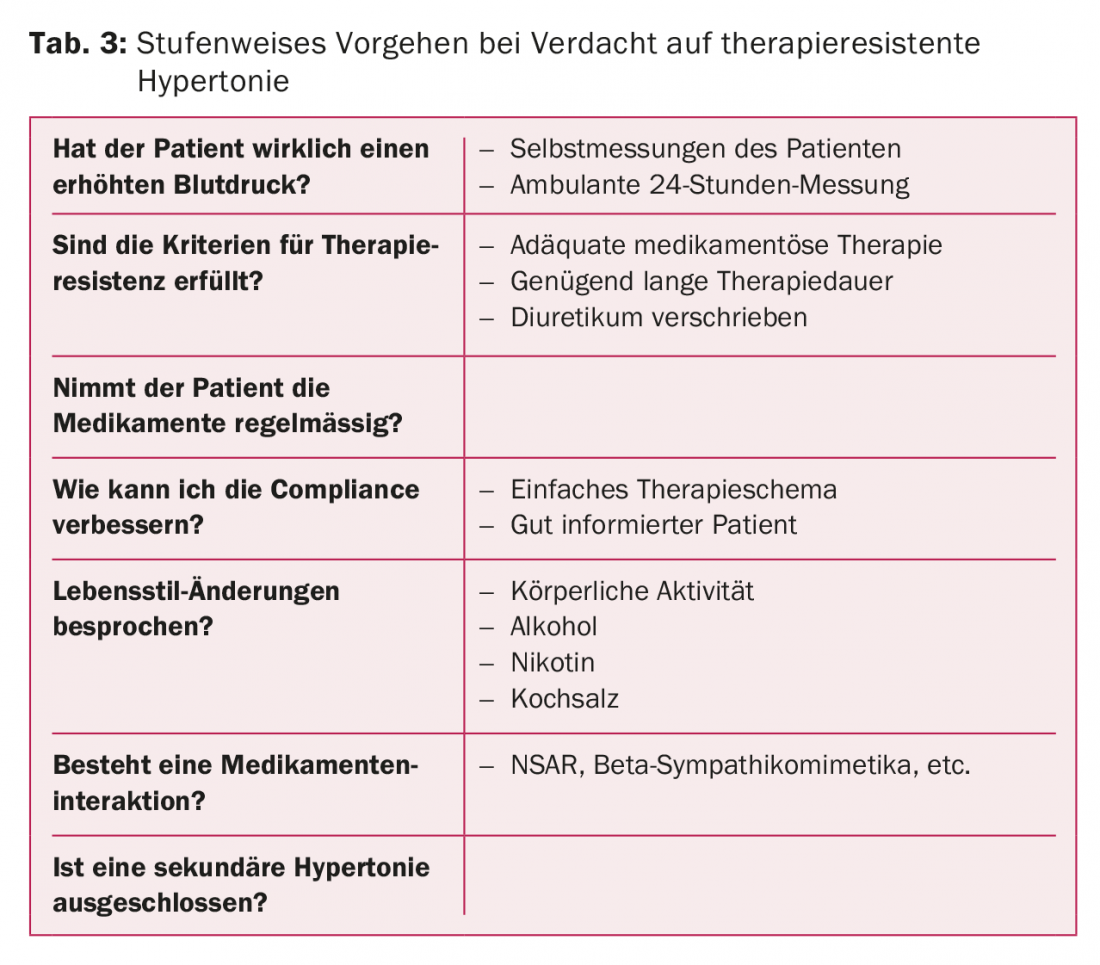

Prof. Battegay recommended clarifying five questions when treatment resistance is suspected:

- Is the blood pressure permanently elevated?

- Are there additional risk factors?

- Is there end-organ damage?

- Has secondary hypertension been ruled out?

- What are the comorbidities? (Tab. 3)

Patients with metabolic syndrome or diabetes have a higher incidence of treatment resistance. Often there is isolated systolic hypertension, blood pressure drops insufficiently at night, and orthostasis is more common. Accordingly, the cardiovascular risk of these patients is two to four times higher (CHD, renal failure, heart failure, stroke, etc.). Because of the lack of “dipping,” at least one of the antihypertensives should be taken in the evening.

Another risk factor for treatment resistance is obstructive sleep apnea syndrome (OSAS), which affects 2-4% of men and about 1% of women. These patients may have higher blood pressure at night than during the day (masked hypertension). CPAP therapy not only improves sleep quality, but also lowers blood pressure levels – both at night and during the day.

Many patients with hypertension also suffer from joint pain: this can increase blood pressure, but NSAIDs used to treat the pain also increase blood pressure (volume retention, decreased vasodilation). “Unfortunately, there are no guidelines on how to proceed in such a situation,” Prof. Battegay said. “It’s a matter of making an individual decision.”

In case of real resistance to therapy, the drug regimen should first be optimized (adjustment diuretics, aldosterone antagonists). Alpha blockers, mi-noxidil, or centrally acting sympatholytics may be evaluated as second-line therapy. Additional therapeutic options, but only used in special cases, include catheter ablation of renal sympathetic nerves, electrical stimulation of carotid sinus baroreceptors, and central arteriovenous anastomosis.

Ambiguity in hypertension target values.

Prof. Dr. med. Andreas Schönenberger, Geriatric University Hospital Bern, became somewhat nostalgic in his lecture: “Everything used to be much simpler, including the target values for hypertension.” In 2005, 140/90 mmHg applied to all, resp. 130/80 mmHg for patients with diabetes or renal insufficiency. Today, there are a variety of guidelines, national and international, with different target values. “It’s a huge mess!”

With regard to the SPRINT study, the speaker noted that it refers primarily to seniors who tend to be fit, since sicker ones were not allowed to participate in the study at all. In daily practice, however, the elderly often have comorbidities that severely limit their life expectancy and/or quality of life, such as dementia. How low (if at all) should excessive blood pressure be lowered in these individuals? The CRIME criteria provide practical recommendations in this regard [4]:

- In patients with dementia or marked functional limitations, strict blood pressure lowering (<140/90 mmHg) is not recommended.

- In patients with dementia or marked functional limitations, hypertension treatment with more than three antihypertensive agents should be avoided.

- In patients with a life expectancy of less than two years, strict blood pressure reduction (<140/90 mmHg) is not recommended.

- If falls occur as a result of orthostatic hypotension (or symptomatic orthostatic hypotension), the number of antihypertensive drugs should be reduced.

Individual target values in the elderly

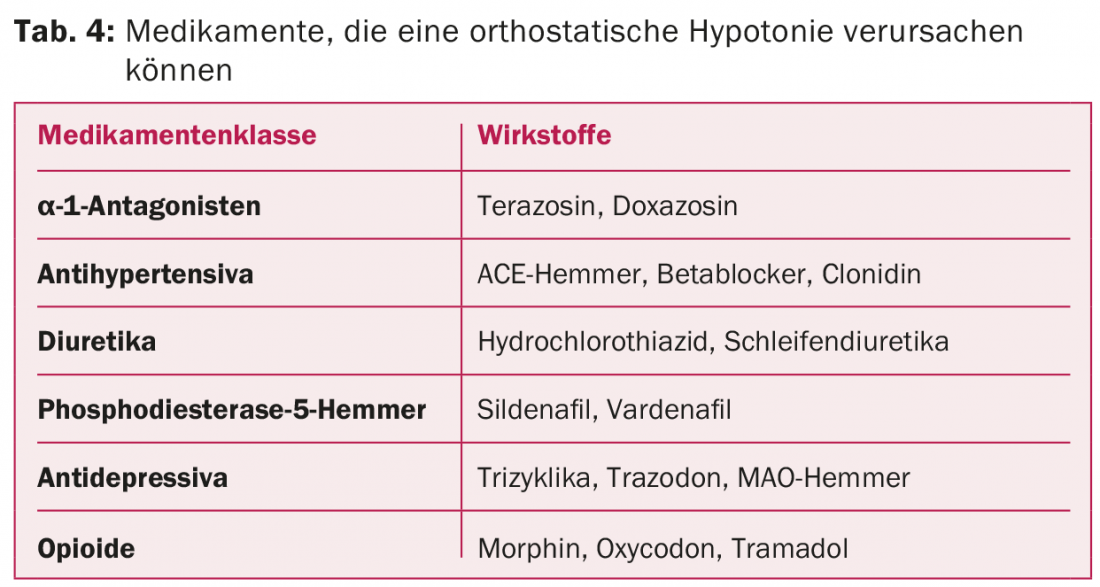

In practice, people often forget to diagnose cognitive impairment or dementia. However, this diagnosis is particularly important in determining the indication for hypertension therapy and target blood pressure levels. In addition, dementia can greatly affect compliance. “If blood pressure levels are lowered too much, there is a risk of orthostatic problems or decreased organ perfusion, which, in the case of the brain, can negatively affect cognition,” the speaker said. “Because of the concomitant reduction in diastolic blood pressure, myocardial ischemia may also develop.” Orthostatic hypotension becomes more common with age, possibly caused by medications (Table 4) . The orthostasis problem often results in the inability to achieve target blood pressure values.

However, advanced age alone is no reason to forgo good blood pressure control. Prof. Schönenberger presented a 90-year-old patient with a long list of diagnoses who had repeated falls (in addition to arterial hypertension, he had coronary artery disease, COPD, mild cognitive impairment, mild renal insufficiency, hypothyroidism, and vitamin deficiency, among others). In this patient, it is worthwhile to keep blood pressure well controlled and minimize the risk of falls by expanding medication: “None of the patient’s diagnoses directly reduce life expectancy. At the same time, he is at very high risk for cardiovascular events or stroke. Such an event would be a double disaster because the patient is caring for his wife, who has dementia.”

The optimal blood pressure setting is the responsibility of the general practitioner. In the hospital, patients are often stressed and they are given medications that potentially increase blood pressure. Therefore, it is important for the primary care physician to review and, if necessary, adjust antihypertensive therapy in patients coming out of the hospital.

Take-home messages from Andreas Schönenberger

- Blood pressure targets may be relaxed if life expectancy is expected to be less than one to two years, especially in advanced dementia.

- Target values should be determined individually in elderly patients, depending on biological age and drug tolerance.

- In fit older patients and with good tolerance of therapy, the same target values should be aimed for as in younger patients.

- Keep an eye on reduced perfusion of organs (brain, kidney, heart) and orthostatic hypotension and relax target values if necessary.

Source: 11th Zurich Hypertension Day, January 21, 2016, Zurich

Literature:

- SPRINT Research Group: A Randomized Trial of Intensive versus Standard Blood-Pressure Control. N Engl J Med 2015 Nov; 373(22): 2103-2116.

- Hodgkinson J, et al: Relative effectiveness of clinic and home blood pressure monitoring compared with ambulatory blood pressure monitoring in diagnosis of hypertension. Systematic review. BMJ 2011; 324: d3621.

- Powers BJ, et al: Measuring blood pressure for decision making and quality reporting. Where and how many measures? Ann Intern Med 2011; 154: 781-788.

- Onder G, et al: Recommendations to prescribe in complex older adults. Results of the CRIteria to assess appropriate Medication use among Elderly complex patients (CRIME) project. Drugs Aging 2014; 31(1): 33-45.

CARDIOVASC 2016; 15(2): 28-31