Chronic low back pain may have a defined pathomorphologic correlate; the main difficulty remains the detection of this correlate. The gold standard of evaluation for back pain is history, clinic, and ap/lateral standing radiograph and MRI. Disc degeneration, facet arthrosis, and segmental instability (insufficiency) are common causes of specific low back pain. Patients with a morphologic correlate for their low back pain should not be denied surgery for too long.

The term “low back pain” (lumbago, lumbospondylogenic syndrome, lumbovertebral syndrome with or without pseudoradicular radiation) is very imprecise and refers to a variety of complaints. In 80-90% of patients who seek medical treatment for back pain, it is so-called non-specific pain that is not triggered by a defined, recognizable pathology. In contrast, the remaining 10-20% of patients have specific pain: there is a defined, structural change that explains the back pain.

Not only for non-specific low back pain, but also for specific low back pain, non-surgical treatment is the treatment of first choice. If non-surgical therapy remains unsuccessful, surgery may be discussed if there is an appropriate morphologic correlate. However, even with structural changes in the spine, it can only be assumed with a high degree of probability that these explain the pain. Thus, the indication for surgery for low back pain remains a priori a complicated process of knowledge and experience.

This two-part article focuses on surgical options for degenerative low back pain without radicular symptoms. Nerve compression syndromes, as seen in disc herniations, or claudication symptoms secondary to stenosis will not be discussed here. In part 1, the diagnostic methods will be presented, in part 2 in the next issue of HAUSARZT PRAXIS, the surgical options.

Low back pain as a result of degenerative changes

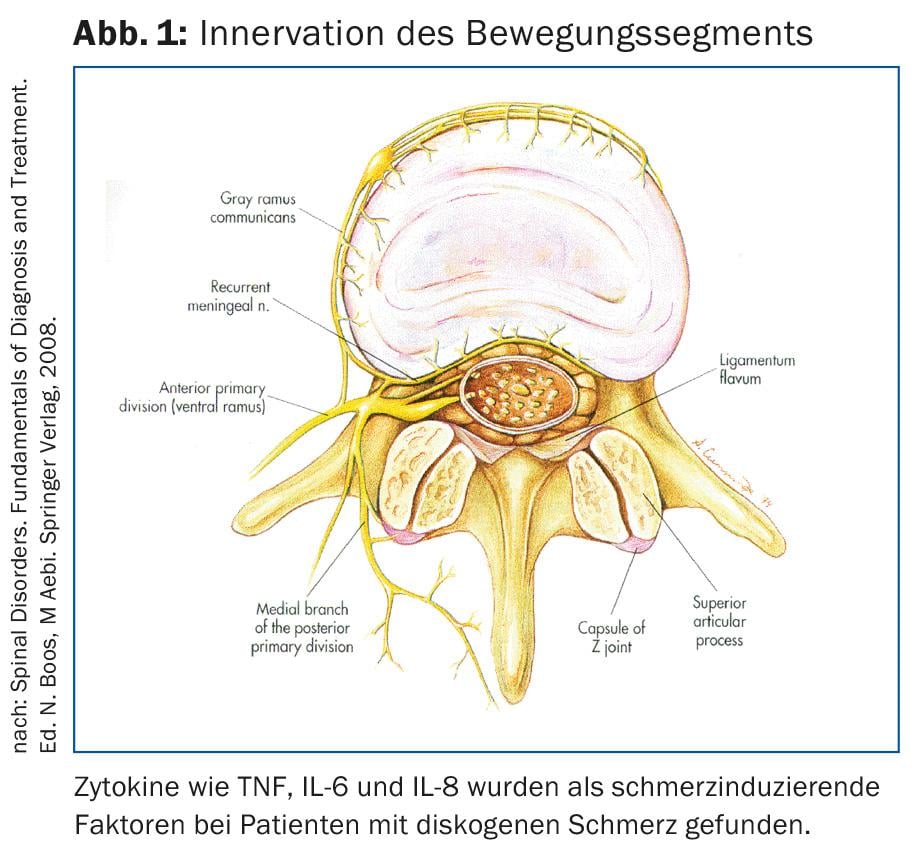

Most specific low back pain is caused by degenerative changes; causes such as tumors, trauma, osteoporotic fractures, and infections are rare (Table 1). All structures of the motion segment may be degeneratively altered: Intervertebral disc, vertebral body with end plates, ligaments, facet joints and muscles (Fig. 1).

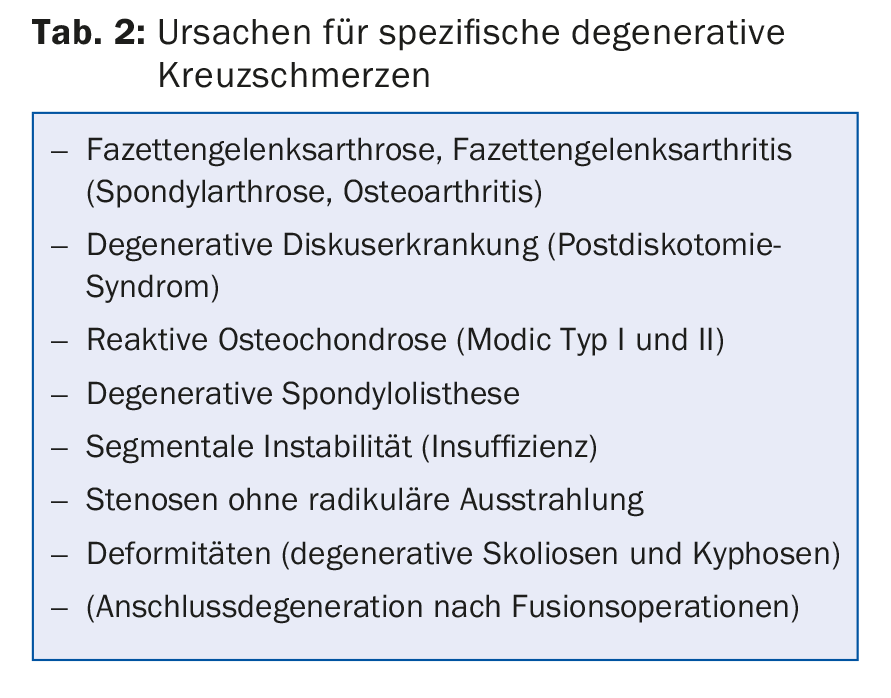

Often several of these structures are degeneratively altered, so that one speaks of a segmental degeneration. The most common structural causes of low back pain are thought to be degenerated discs (Table 2).

Older people don’t have more back pain than a comparable younger collective: you don’t have back pain just because you’re old. Even in old age, structural changes are often present, which explain the pain very well.

The degenerative “instability

In the case of degenerative changes, the term “instability of a movement segment” does not mean a pathologically increased extent of movement, but the abnormal movement under physiological load. Since this term is somewhat unfortunate, the author prefers the term “segmental insufficiency.” It is suspected that as a result of disc degeneration, the force in the disc is no longer transmitted homogeneously from vertebra to vertebra and pressure peaks occur, stimulating the nociceptors in the annulus. The arthritically altered facet joint is also a source of pain. The facet joints are innervated by nociceptive fibers of the medial branches of the spinal nerves. Not only arthritis, but also mechanical overload could cause pain.

Clinical examination

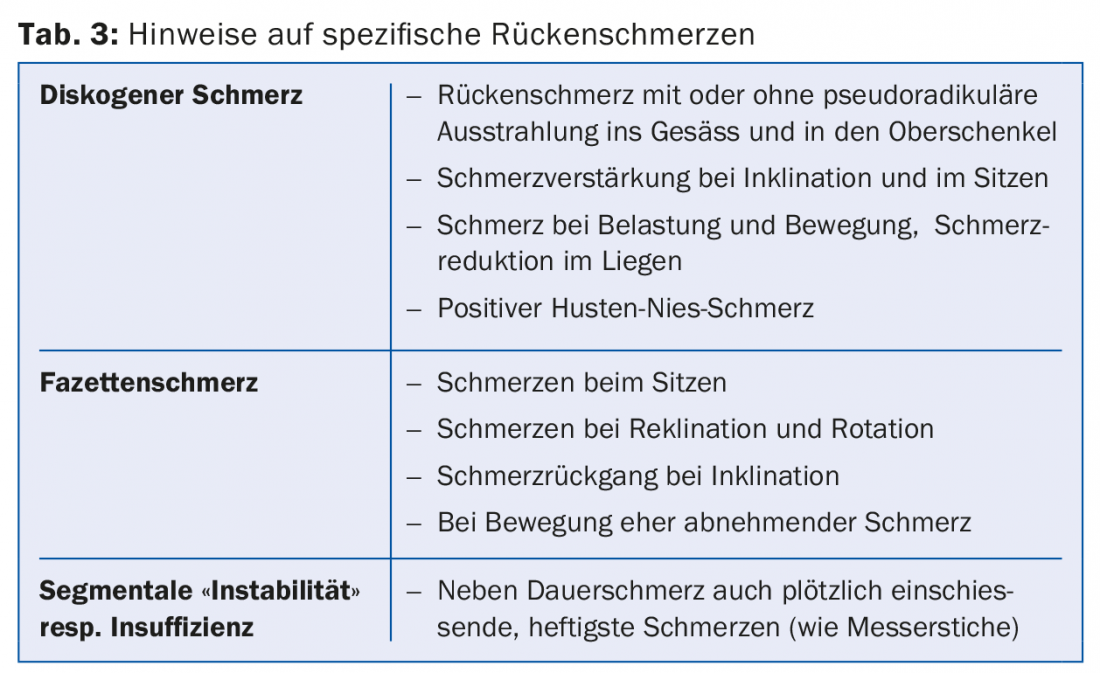

Pain history is an important tool for the spine surgeon. The patient’s own narrative may indicate whether or not a specific structural change in the lumbar spine explains the pain (Table 3) . Clinical and neurological examination are also essential components in clarifying the source of pain. The prevalence of discogenic is thought to be around 39%, and facet-only pain is less common [1]. Assuming that facet infiltration is diagnostic, the prevalence of facettogenic low back pain is reported to be 7.7-75% with unilateral infiltration and 15-40% with bilateral infiltration.

Imaging techniques

The gold standard of evaluation for back pain is the ap/lateral standing radiograph and MRI. Imaging while standing represents a stressful situation, unlike MRI, which is performed while the patient is lying down. The radiograph shows disc degeneration, possibly with spondylophytes as a sign of possible instability, and severe spondyloarthritis. MRI is not a reliable tool for detecting discogenic pain. Despite MRI, correlation between age-related changes and symptoms remains difficult. Soil et al. found degeneration and narrowing of the discs in asymptomatic individuals in 35% of 20- to 39-year-olds and in virtually all 60- to 80-year-olds [2]. Evans et al. found disc degeneration in 26-57% [3]. By age 65, 99% of asymptomatic individuals also have degenerative changes [2,4–6]. However, individuals younger than 50 years have fewer disc extrusions (18%), no disc sequestra, rarely endplate changes (3%), and never facet joint arthritis. But there are changes that are very often accompanied by back pain. In particular, modic type I changes (bone marrow edema) have a high correlation with discogenic pain (Fig. 2) . Severe and moderate endplate changes type I and II showed 100% concordant pain provocation in a discography [7]. In contrast, a hyperintense zone (HIZ) in the dorsal annulus of the disc is not a definite indication of discogenic pain and often occurs even in asymptomatic individuals.

Infiltrations for clarification of a surgical indication

Facet infiltrations can help in the initial treatment and relieve symptoms. In patients who are no longer responsive to infiltration, this can be used as a diagnostic criterion for the indication of surgery. Provocative discography is another helpful tool for establishing indications, but it is not suitable as a routine procedure for detecting discogenic pain. In individual cases, it may provide additional information in patients who are candidates for surgery, such as whether to include additional segments in fusions. However, provocative discography has not been shown in studies to improve patient selection and thus outcome after surgery. Therefore, the author uses discography only in exceptional cases when discogenic pain alone seems likely based on clinical and magnetic resonance imaging examination.

You will find part 2 of this article in the next issue of HAUSARZT PRAXIS.

Literature:

- Carragee EJ, et al: Discographic, MRI and psychological determinants of low back pain disability and remission: a prospective study in subjects with benign persistent back pain. Spine J 2005; 5(1): 24-35.

- Boden SD, et al: Abnormal magnetic resonance scans of the lumbar spine in asymptomatic subjects. J Bone Joint Surg Am 1990; 72A: 403-408.

- Evans W, et al: A cross-sectional prevalence study of lumbar disc degneration in a working population. Spine 1989; 14: 60-64.

- Boos N, et al: 1995 Volvo Award in clinical sciences. The diagnostic accuracy of magnetic resonance imagimg, work perception, and psychosocial factors in identifying symptomatic disc herniations. Spine 1995; 20: 2613-2625.

- Borenstein DG, et al: The value of magnetic resonance imaging of the lumbar spine to predict low back pain in asymptomatic subjects. J Bone Joint Surg Am 2001; 83A(9): 1306-1311.

- Jensen MC, et al: Magnetic resonance imaging of the lumbar spine in people without back pain. N Engl J Med 1994; 331: 69-73.

- Weishaupt D, et al: MR images of the lumbar spine: prevalence of intervertebral disk extrusion and sequestration, nerve root compression, end plate abnormalities, and osteoarthritis of the facet joints in asymptomatic volunteers. Radiology 1998; 209: 661-666.

HAUSARZT PRAXIS 2016; 11(2): 26-28