Although there are clear guidelines on which investigational modality is used for which question, the decision is plurifactorial. If in doubt, you can ask the radiologist for advice. Medical history and clinical information are immensely important for the radiologist to select the correct examination protocol. For CT examinations, a specific question helps to choose the protocol with the lowest radiation exposure. For MRI examinations, it is important to narrow down the region to be examined for technical reasons. History and clinical status cannot be substituted for radiologic examination.

The question of computed tomography or magnetic resonance imaging (CT/MRI) should be raised only after conventional radiography or ultrasound, since these modalities already narrow the differential diagnosis and may make further investigation unnecessary. A conventional x-ray is often helpful: for example, it may show a femoral neck fracture and the patient does not have to wait a week for an MRI scan.

CT and MRI are outwardly very similar, but technically very different with different strengths and weaknesses. The CT unit is a ring when viewed from the outside. The examination time is short, even for large regions, and the size of the region to be examined can still be adjusted as desired during the examination. But you need X-rays for CT, so for radiation protection reasons it is important to ask the question as precisely as possible. The MRI system, on the other hand, is a tunnel. The examination takes longer and the size of the region to be examined is limited by the antenna size and cannot be adjusted arbitrarily. Precise questioning is important in MRI for establishing the examination protocol.

CT has a bad press due to the X-rays required, whereas MRI appears to be an almost omnipotent examination method. Therefore, it is all the more difficult to decide in favor of one or the other examination modality. Thus, the most important technical differences and indications will be discussed here.

Computed tomography

CT is a cross-sectional imaging technique that uses complex mathematical algorithms to create an image through the tissue-specific absorption of X-rays. CT has important advantages:

- Quickly available

- Short examination time

- Relatively insensitive to motion artifacts

- The region of interest is acquired as a volume, this allows for image reconstructions in all axes later (MPR)

- The examination room is easily accessible; this is important in unstable patients.

Disadvantages of CT, apart from radiation exposure, are that it is less sensitive and specific for inflammatory changes in soft tissues and bone structures and has lower spatial contrast for soft tissue structures.

Magnetic resonance imaging

MRI is a cross-sectional imaging technique that uses the different behavior of water molecules (proton mini-magnets) in different tissues of the body in the magnetic field. This results in different energy signals, which in turn are recorded by the antennas and then translated into an image using mathematical algorithms. MRI does not result in radiation exposure, shows very good spatial resolution of soft tissue structures, and is very sensitive to edematous changes in soft tissue and bone structures. Significant disadvantages of MRI are:

- Long examination time; a cranial examination takes about 50 minutes.

- The region to be investigated is size-limited due to the antenna.

- Not so easily accessible – often longer waiting times

- Artifact prone: magnetic field interference, motion artifacts, metal in the examination field.

- Patient cooperation is important for image quality, so examination is difficult in demented or agitated patients.

- The patient must be able to lie on his back. Breathing difficulties, pain that has not been adequately treated, or hyperkyphosis make examination difficult or impossible.

- The room conditions are very tight: claustrophobia!

- There is a very strong magnetic field (1.5-3 Tesla, this is up to 70 000 times stronger than the Earth’s magnetic field) in the examination room. This means that all objects in the room must be amagnetic, otherwise they pose a danger to the patient.

- Comparatively expensive investigation.

Decision parameters

The major technical differences listed influence the decision of whether to perform MRI or CT. Additional decision parameters are the clinical condition of the patient and the time course of his complaints. Thus, in principle, CT is the investigation of choice in an agitated patient with rapid deterioration of condition. The decision also depends on whether a clinical picture is acute or chronic and which organ system is affected. The decision is relatively simple, especially for the craniocervical region or in the musculoskeletal region, where the examination protocols are fairly uniform and relatively independent of pathology. However, the examination protocols of the thoracic-abdominal region are much more complex depending on the problem and pathology. Two examples:

Thoracic CT: When pulmonary embolism is questioned, the image is timed for intravascular contrast and specifically weighted for maximal contrast in the pulmonary arteries. In contrast, a mixed image is desired for a standard CT of the thorax, that is, imaging in which contrast is seen in both the aorta and pulmonary vessels.

Abdominal CT: Depending on the question, the examination must be performed iv, orally and/or rectally with or without contrast medium. In addition, the question also determines whether one needs only a passage across the abdomen or whether one needs to include contrast distribution dynamics in the diagnosis. The number of passages is ultimately responsible for the patient’s radiation exposure per examination.

Indications by region and pathology

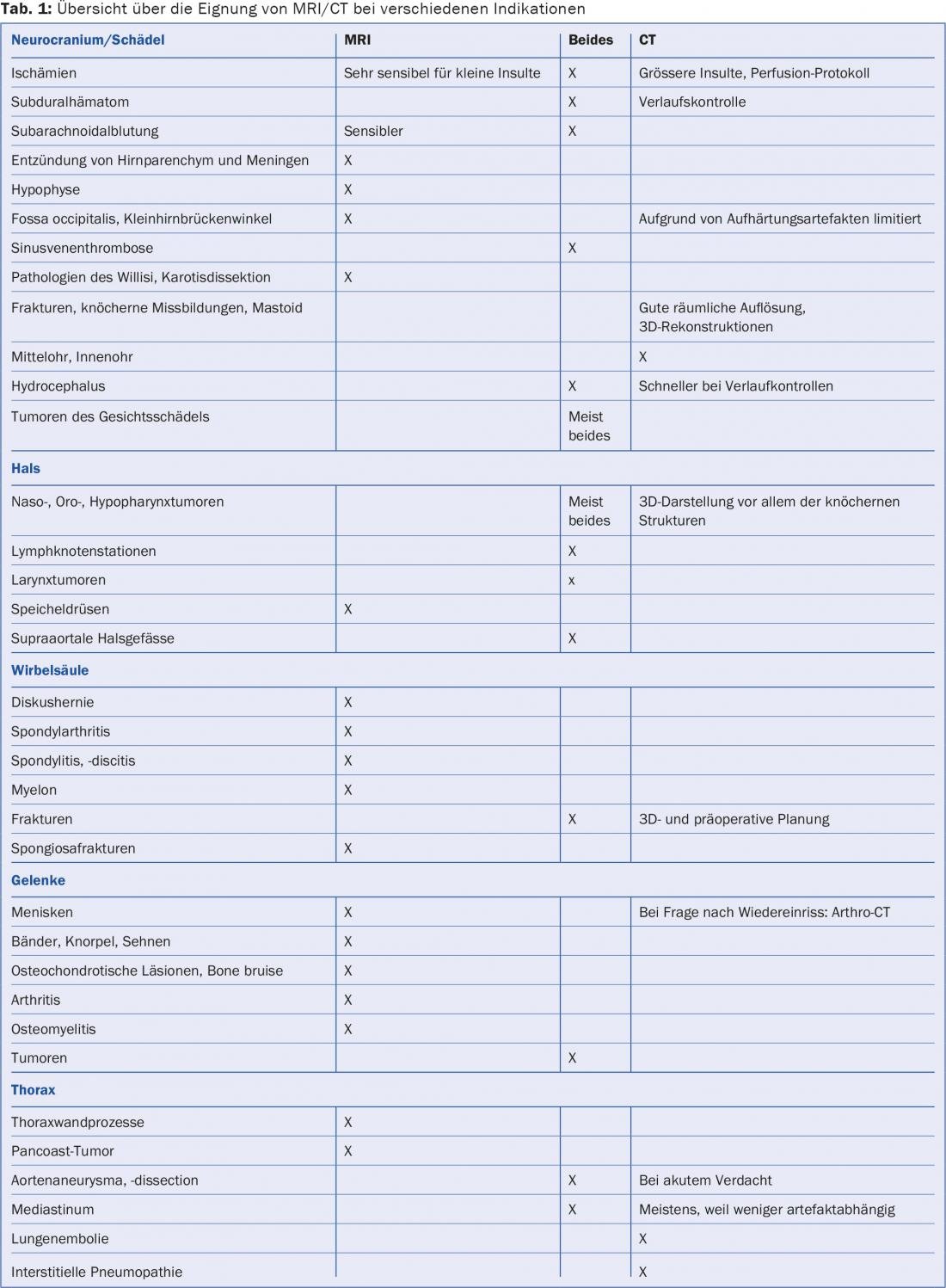

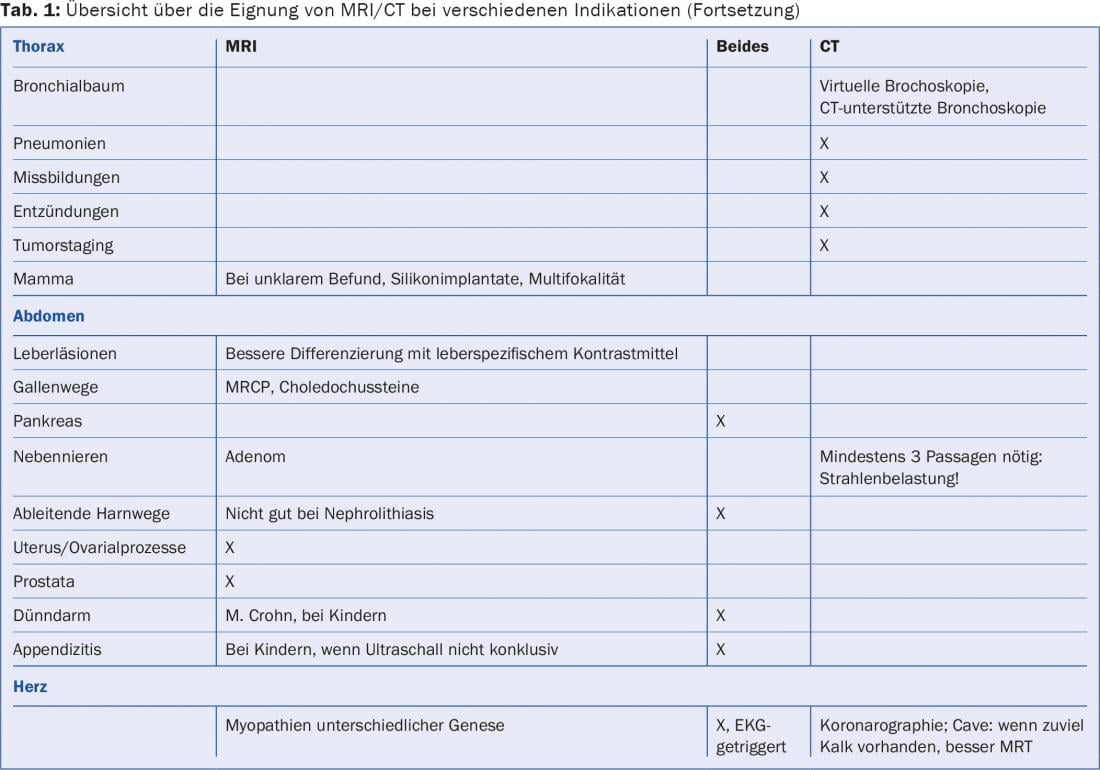

In the following, some indications are explained according to region and pathology. The list is not exhaustive, but the most important pathologies should be mentioned (Tab. 1).

Skull CT

- In acute onset of central nervous dysfunction and rapid deterioration, this is the first choice for diagnosis of intraparenchymal, subdural, and subarachnoid hemorrhage as well as ischemia and acute cerebrospinal fluid flow disturbances.

- Primary examination in head trauma: for good fracture analysis and 3D analysis.

- Inner ear, bony parts

- Sinuses

- ENT tumors

- CAVE: Analysis of the cerebellopontine angle and occipital fossa is limited due to hardening artifacts.

Cranial MRI

- If ischemia is suspected

- In trauma, for visualization of even very small lesions such as axonal lesions and microhemorrhages

- Inflammatory changes of the brain substance (e.g. in multiple sclerosis) and the meninges

- Tumor detection and metastases

- Cerebellopontine angle, inner ear, middle ear

- Tumors of the ENT sphere

- Temporomandibular joints

- Angiography of the intracranial arterial and venous vascular axes

- Dementia, epilepsy

Neck CT

- Trauma of the cervical spine (HWS)

- Visualization of the bony portions in the context of neuroforaminal stenosis.

- Malformation of the cervical spine: 3D reconstructions are possible

- ENT tumors and possible lymph node involvement

- Angiography of the supraaortic vascular axes

- CAVE: not for thyroid tumors due to iodine exposure.

- Neck MRI

- Posttraumatic: ligamentous lesions, bone edema, brachial plexus

- Disc hernia

- Myelopathy: post-traumatic, inflammatory, degenerative changes.

- Tumors

- Inflammatory-degenerative changes of the cervical spine

- Supraaortic vascular axes

Thoracic CT

- Pulmonary embolism

- Tumors of the lung and mediastinum

- Interstitial pneumopathy

- ECG-triggered cardio-CT coronarography.

- CT-guided biopsies and drains

Thoracic MRI

- Thoracic spine: inflammatory, degenerative,

- traumatic, tumorous changes

- Disc hernia

- Myelon

- Triggered cardiac examinations

- Soft Tissue Tumors

- Mamma

Abdomen CT

- Posttraumatic

- Liver, gall bladder, pancreas – especially with acute cause

- Kidneys and urinary tract, especially in nephrolithiasis, pyelonephritis and tumors.

- Small and large intestine

- Arterial and venous vascular axes

- Virtual colonoscopy: tumor screening or when the gastroenterologist is unable to pass through the colon or can only pass partially through the colon. CAVE: acute diverticulitis is a contraindication.

- Bony structures: post-traumatic, metastases, preoperative

Abdomen MRI

- For overview examination of the entire abdomen without a specific question, MRI is not very well suited despite great technical advances.

- Usually as an additional examination to CT for more precise specification, e.g., of liver lesions, thanks to liver-specific contrast media.

- gallstones, especially choledochal stones

- Evaluation of chronic pancreatitis with functional secretin test

- Follow-up of inflammatory bowel changes such as Crohn’s disease and in children

- Organs of the small pelvis

- CAVE: unsuitable for detection of nephrolithiasis.

Joints

- For joints, the MRI examination is the first priority. Only rarely is a CT required, especially in the context of surgical planning, for a better assessment of the bone structures.

- CT of joints is appropriate when MRI is contraindicated.

- Arthro-CT if there is a question of a new meniscus tear or if MRI is not possible.

Conclusion

As can be seen from the indications given for one or the other examination modality, the decision whether to use MRI or CT cannot always be answered unambiguously. In addition, other factors also influence the decision for or against one or the other modality, for example renal insufficiency, contrast agent allergies or claustrophobia.

Unfortunately, the impatience of the patient and/or referring physician often plays a role as well, since there is usually a longer wait for an MRI examination appointment.

In any case, an investigation that cannot answer the question is too expensive.

Further reading:

- ACR-Appropriateness Criteria-American College of Radiology (www.acr.or/Quality-Safety/Appropriateness-Criteria)

- Eisenberg RL, et al: Radiologypocket reference: what to order when. Lippincott-Raven.

- Trueb PR: Compendium for medical radiation protection experts, Haupt Verlag.

- Procop M, Galanski M: Computed tomography of the body, Thieme Verlag.

- Weishaupt D, et al: How does MRI work?, Springer Verlag.

- Weissleder R, et al: Primer of diagnostic imaging, Mosby.

- Dähnert W: Radiology Review Manual, Lippincott.

- Osborn AG, et al: Diagnostic imaging – Brain, Amyrsis.

- Harnsberger HR, et al: Diagnostic imaging – Head and Neck, Amyrsis.

- Federle M, et al: Diagnostic imaging – Abdomen, Amyrsis.

- Stoller D, et al: Diagnostic imaging – Orthopedics, Amyrsis.

HAUSARZT PRAXIS 2016; 11(1): 33-34