Many patients complain of shoulder or back pain in their family doctor’s office. Clarification and therapy are often very complex – especially in the shoulder area, there are numerous anatomical structures that can trigger pain. At Medidays, Prof. Christian Gerber, MD, provided information on the most common clinical pictures, useful diagnostic steps and treatment options for shoulder pain. The presentation by PD Mazda Farshad, MD, focused on spinal stenosis.

An everyday situation from the practice: A patient presents with shoulder pain that is so severe that it prevents him from sleeping and he can no longer dress well. However, the mobility of the shoulder is normal. What next?

Prof. Dr. med. Gerber recommended having the patient describe the pain in detail. It should also show where it hurts. Pain proximal to the acromio-clavicular joint (AC joint) that radiates to the neck and trapezius often originates from the AC joint. This is so close under the skin that patients can usually use a finger to show where the pain point is. Pain over the outside of the proximal humerus is more suggestive of a problem in the subacromial space. In the anamnesis it is important to ask about traumas – also about “minitrauma”, for example in sports, and about traumas of the hand (indirect shoulder trauma).

Painful AC joint

Pain originating from the AC joint may be directly induced by pressure on examination. Since the pain often radiates into the neck, it is often suspected that the cervical spine is affected. Passive hyperabduction is also painful. A conventional X-ray, a-p and possibly axial, is suitable for clarification. As therapy, NSAIDs should be given for ten days; physiotherapy usually does not help. After the ten days, injecting a steroid into the AC joint can bring about improvement; if you are unsure yourself, a radiologist can also do the injection. If there is improvement with partial recurrence, the injection is repeated, but if the pain returns as severe as it was at the beginning, the patient should be referred to an orthopedist.

Frozen shoulder

Diagnostic for a “frozen shoulder” (periarthropathia ankylosans, post-traumatic frozen shoulder) is the following sequence: After trauma, the pain decreases slightly for two to three days, but then it increases again and is also present at night. At the same time, the mobility in the shoulder decreases. However, a “frozen shoulder” can also occur idiopathically, without previous trauma. On examination, passive range of motion in the shoulder joint is limited, and the radiograph is normal.

The average duration of the disease is 18-24 (!) months, but the cure rate is very high (95%) – patients must be well informed about this. Suitable therapies include COX-2 inhibitors, calcitonin (intranasal) and, at most, the intake of 1 g of vitamin C per day. If the pain is very severe, a steroid injection, always under imaging, may provide relief. Physiotherapy is only useful if it helps to reduce pain and does not trigger pain itself. Prof. Gerber emphasized that physiotherapy should serve to maintain, not improve, mobility (beware of overzealous physiotherapists!). Clarification by the orthopedist is only necessary if further complaints persist after the reduction of frozen shoulder.

Rotator Cuff Rupture

Rotator cuff rupture is often caused by trauma, but can also occur as a result of degenerative changes. Typical complaints are a sudden reduction in strength and chronic shoulder pain (night pain). Shoulder weakness is most apparent when the elbow is splayed away from the body.

Patients should be referred to the orthopedic surgeon if the loss of strength is unacceptable to the patient or if there are high functional demands on the shoulder joint. “In such a case, don’t wait too long to make the assignment,” Prof. Gerber advised. “You can still treat the pain six months down the road, but you can’t treat the loss of strength.” For conservative therapy, NSAIDs and physical therapy with stretching are appropriate.

Pain when walking: Spinal stenosis or intermittent claudication?

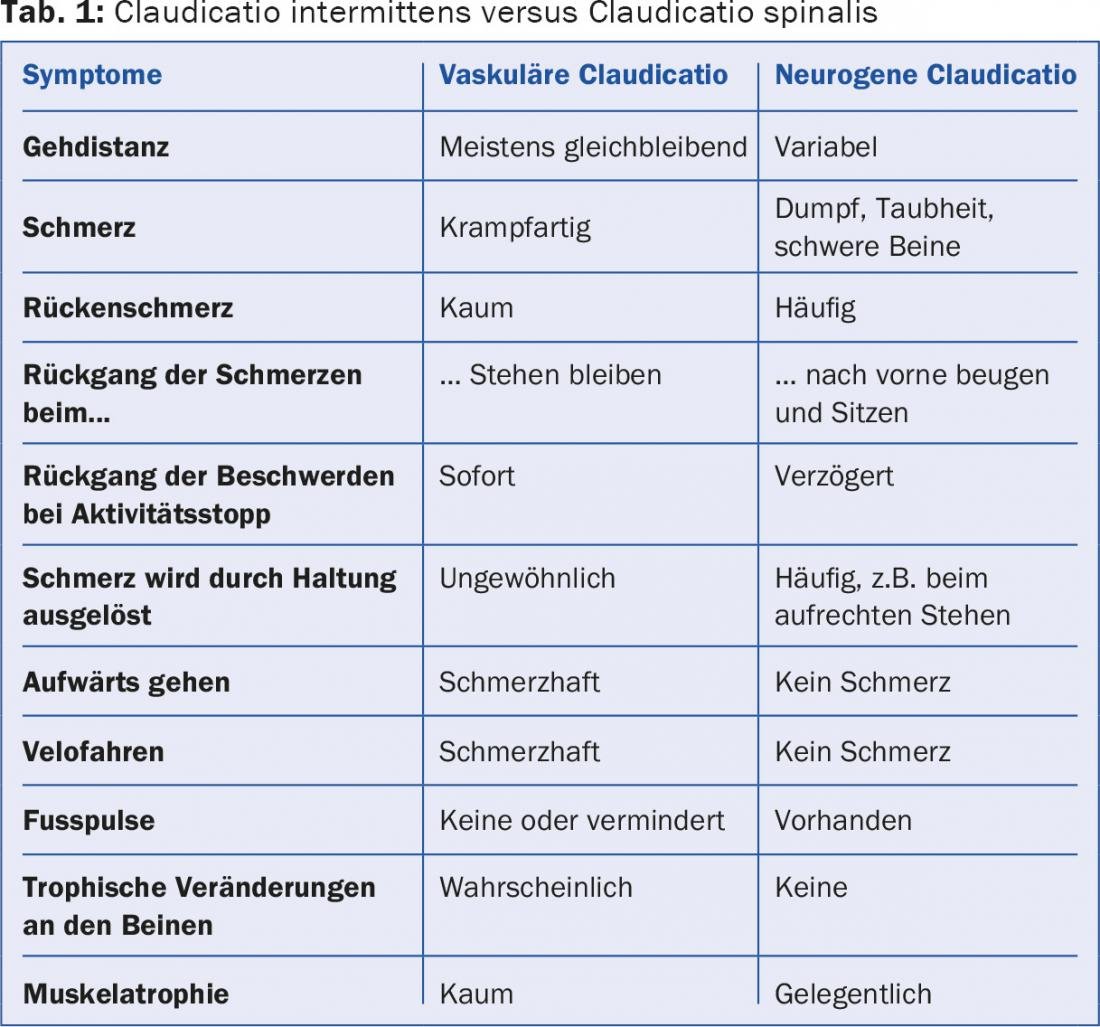

Spinal stenosis is a typical degenerative disease: in more than 80% of all people over 70 years of age, the spinal canal is radiologically narrowed. However, there is poor association between symptoms and radiology. Typical complaints of spinal stenosis are back pain radiating to the legs and buttocks, limited walking distance, a feeling of heaviness in the legs, and tingling paresthesias (spinal claudication). Leg weakness and bladder dysfunction may also occur. Often the pain improves when the patient sits down or leans forward (e.g., over the shopping cart). Causes of the pain are neurogenic on the one hand, but also vascular compression, which leads to reduced blood flow. It is important to distinguish it from intermittent claudication (Table 1).

The workup begins with a conventional x-ray of the spine to rule out degenerative spondylolisthesis, degenerative scoliosis, or congenital stenosis. This is followed by an MRI to determine the degree and cause of the stenosis and also to show the progression of the disease. Neurophysiologic workup is not always necessary but may be useful to quantify neurologic deficits and make the differential diagnosis to peripheral polyneuropathy, because many patients are advanced in age and have comorbidities such as diabetes mellitus.

Therapy of spinal stenosis

In the case of mild symptoms without neurological deficits resp. in the case of severe comorbidities, conservative treatment is used. There is no conclusive evidence for the use of analgesics and physiotherapy, but these measures may provide relief in the individual patient. Epidural steroid infiltrations usually improve symptoms for two to six weeks, but may also induce epidural lipomatosis.

If the patient suffers from progressive or neurogenic symptoms or even cauda syndrome, surgical decompression is required. Spondylodesis may also be necessary if segmental degeneration produces severe lumbar pain or in cases of higher grade listhesis. After the procedure, physiotherapy is useful (four to six weeks, twice a week) so that patients have less back pain in the medium and long term.

Source: Medidays 2015, August 31 – September 4, 2015, Zurich