The point prevalence of chronic pruritus is approximately 13.5% in the general population and 16.8% in the working population. The incidence is approximately 7% per year. As a result of the great variability of causes, classification is difficult. Two approaches have proven successful: classify by neurophysiological or by clinical diagnostic symptoms. A careful history, thorough clinical examination, and extensive laboratory analysis should elucidate possible causes prior to therapy. The primary goal of therapy is to relieve pruritus as quickly as possible. Individual adaptation is gradual and is described in guidelines. Because pruritus is purely subjective, specific “tools” for assessing treatment benefit have been developed and validated by controlled clinical trials. A distinction is made between tools that assess pruritus intensity and those that assess quality of life.

Pruritus can affect only one area of the skin, as in insect bites or wheals, or it can occur all over the body, as in dry skin during the winter season. In these cases, acute pruritus is spoken of as an expression of the body’s internal defense mechanisms. Besides pain, acute pruritus is also an alarm system to remove possible harmful or even toxic substances from the skin.

In these cases, scratching usually brings some relief. However, in some people the pruritus persists for a long period of time, sometimes without any apparent cause.

According to international nomenclature, if the pruritus persists for more than six weeks, it is considered chronic [1–3]. In contrast to the protective or defensive function of acute pruritus, chronic pruritus (CP) represents a significant impairment of quality of life due to the compulsive desire to scratch.

Occurrence

There are now reliable data on incidence and prevalence of CP, summarized in the “Guideline Chronic Pruritus”: Point prevalence is approximately 13.5% in the general population and 16.8% in the working population – incidence is approximately 7% per year [1].

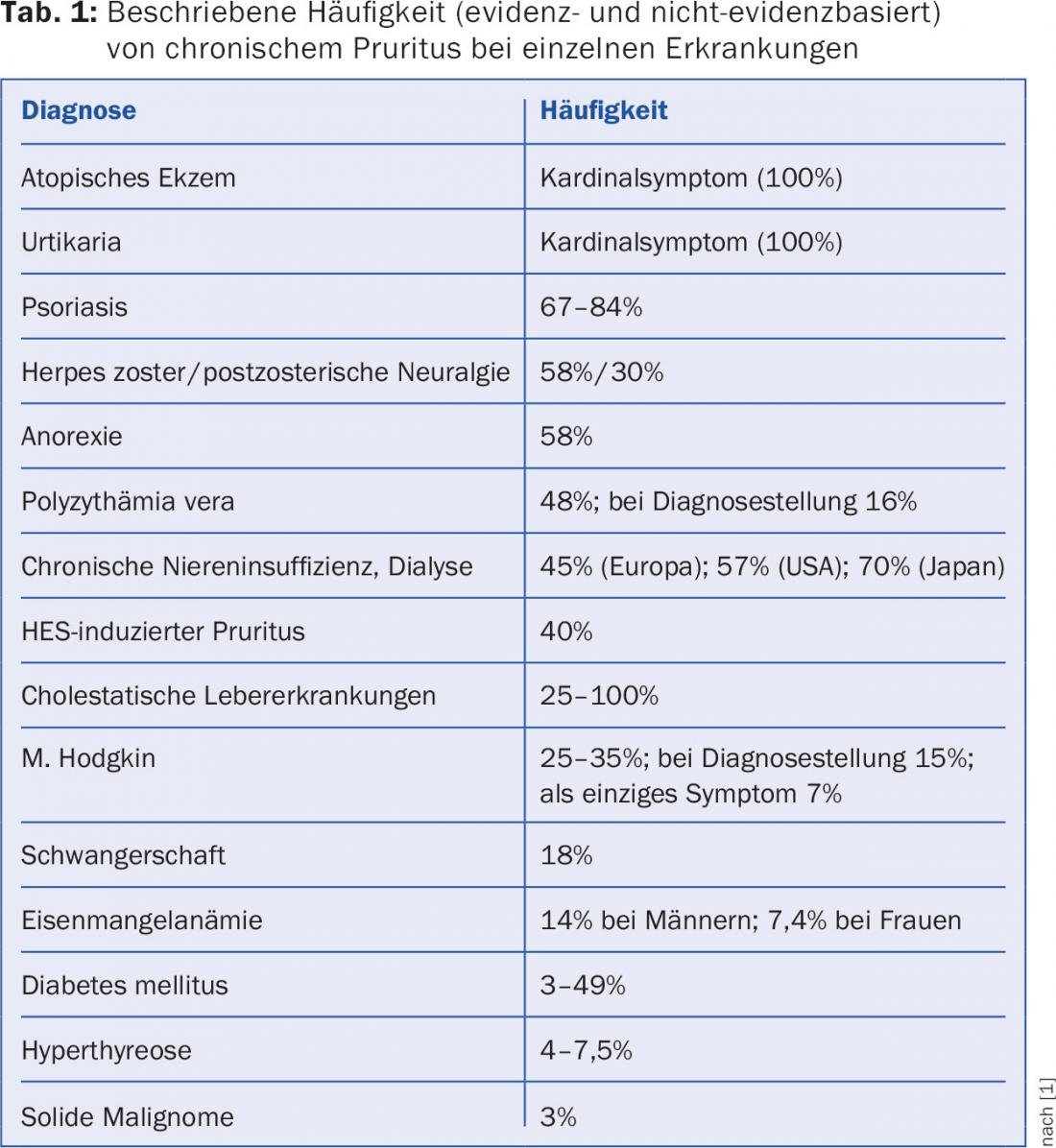

CP is one of the most common dermatological complaints (Table 1), especially in atopic and geriatric patients: 20-33% of those over 85 years of age complain of CP [3] – we refer to the article on “Pruritus in old age” in DERMATOLOGIE PRAXIS 2/2014 [4].

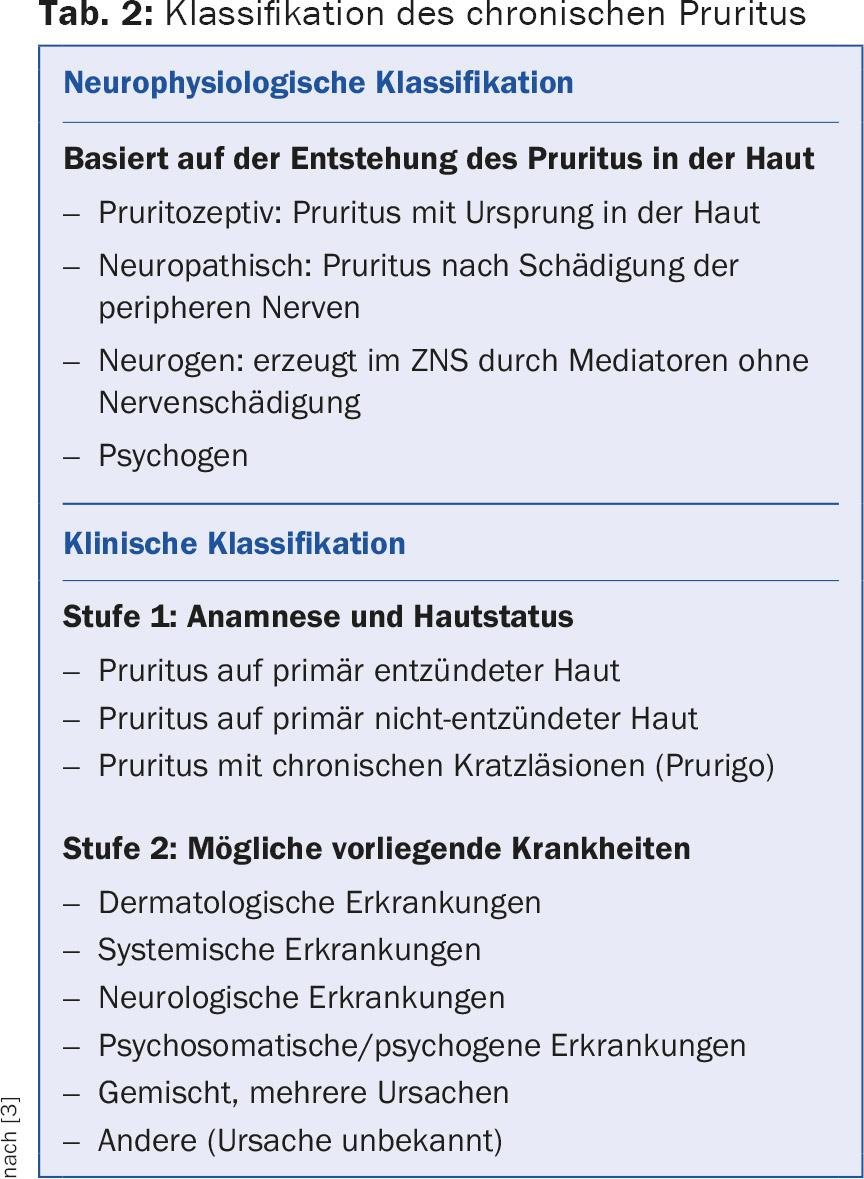

Classification and pathophysiology

As a result of the great variability of causes, classification of CP is difficult. Two approaches have proven successful: Classify by neurophysiological or by clinical diagnostic symptoms (Tab. 2) [1–3,5,6].

The pathophysiology of pruritus is beyond the scope of this text and is described in detail in other publications [2,3,7].

Diagnostics

Due to the multiple causes of CP, there can be no single treatment plan. Beforehand, a careful history, a thorough clinical examination and laboratory analyses should clarify possible causes such as existing diseases, allergy, atopy, medication use, etc. [1,7]. Thorough examination of the entire skin reveals abrasions, ulcerations, erythema, pigmentary shifts, scars, lichenification, and infections or parasitoses that may lead to CP.

It is important to consider scratching methods used by the patient to relieve pruritus (e.g., use of brushes). One also finds the “butterfly sign”, in which scratch lesions are found on the entire back – except for one notch, because the affected person cannot reach there [7]. As a result of the multiple systemic causes of CP, thorough and complete screening for possible disease is essential. In elderly patients, it must also be taken into account that they are often multimorbid.

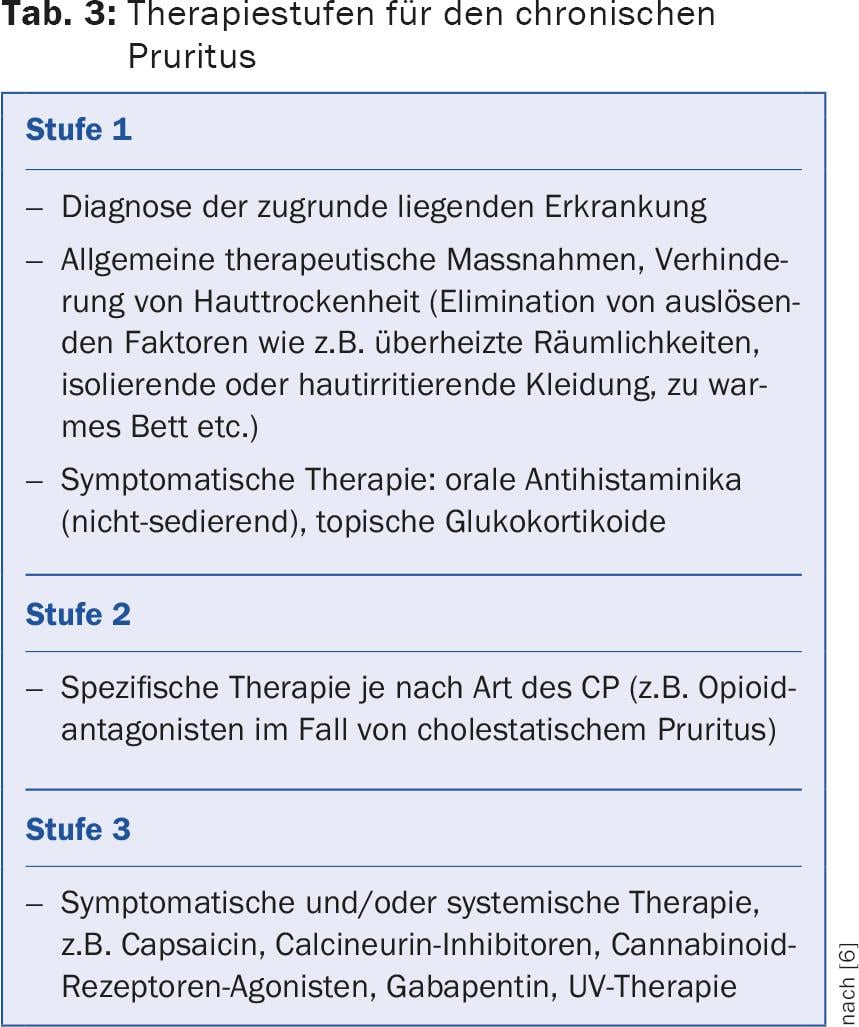

Therapy planning

The primary goal of therapy is rapid relief of pruritus. The great variety of causes usually requires an individually adapted therapy, whereby the skin condition must be carefully monitored in all cases. Individual adaptation is gradual and is described in the guideline (Tab. 3) [1,7]. In all stages, concomitant therapy of sleep disorders (if present), psychosomatic care, behavioral therapy and, if necessary, skin disinfection and local glucocorticoids in case of scratch lesions are indicated.

People who suffer from physically induced itching are often exposed to great physical and mental stress and have to deal with psychological problems. A multidisciplinary approach to therapy is of great benefit and is increasingly recommended [1,4].

Capture pruritus

Pruritus is purely subjective and the benefit of a therapy cannot be proven in the classical sense, e.g. by measuring physiological parameters. Also, intraindividual variations (e.g., as a result of fatigue, anxiety, or stress) can significantly affect the sensation of pruritus [8–10]. Therefore, specific “tools” have been developed and validated by controlled clinical studies. A distinction is made between tools to assess pruritus intensity and tools to assess quality of life.

Tools to capture the intensity

Questionnaires: In order to be able to record CP, questionnaires have been applied again and again. However, there is no internationally standardized questionnaire yet, clinical validations are currently underway [8–11].

VAS: The Visual Analog Scale (VAS) is the basic tool most commonly used. It was originally developed to capture pain. This is a 10 cm line (with only the endpoints labeled 0 = no pruritus and 10 = most severe pruritus imaginable). The patient marks the point on the line that he or she thinks best corresponds to his or her pruritus sensation [8–10].

VRS: In the Verbal Rating Scale (VRS), the severity of pruritus is represented with graded adjectives (0 = no pruritus, maximum 5 = very severe pruritus).

Tools to capture the quality of life

PBI-P: The Patient Benefit Index (version for patients with pruritus, PBI-P) is a standardized questionnaire [8,12]:

- The first version surveys how relevant various benefits of previous therapy are to the patient before treatment.

- The second version surveys the extent to which each benefit of the current therapy was achieved after treatment.

DLQI: The Dermatologic Quality of Life Index (DLQI) measures health-related quality of life. The DLQI was developed in 1994 and has become indispensable for assessing distress. There is now also a version for children [8,13].

PBI-P and DLQI are provided by the authors for payment of small license fees.

Finally, scratching activity is evaluated by thorough examination of skin condition, although this parameter is significantly influenced by external factors and is not necessarily reliable [8].

A multidisciplinary approach is of great advantage in CP therapy [1,4]. Anxiety and depression in pruritus patients are assessed with the Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale (German version: HADS-D) [8]. The HADS-D has been shown to be useful, showing a significant association with the VAS and with the DLQI. Thus, it evaluates the association of pruritus with anxiety or depression [8].

Therapy outlook: new developments

The staged approach involves topical therapy first, which must be adapted to the patient. Topically applied vanilloid alkaloids such as capsaicin or calcineurin inhibitors are promising. New to topical therapy are cannabinoid (CB) receptor agonists. One of these CB receptor agonists is N-palmitoylethanolamine. Several studies have shown the good antipruritic effect of a cream containing a low concentration of N-palmitoylethanolamine in patients with atopic dermatitis [14], with lichen simplex and with CP after hemodialysis and of unknown cause [7].

Regarding systemic therapy, recent evidence shows that substance P (SP) is an important factor in the induction and maintenance of pruritus. SP is a neuropeptide that belongs to the group of neurokinins (formerly known as tachikinins). SP binds to three neurokinin receptors (NKR1-3), mainly to NKR-1. Therefore, a highly selective NKR-1 antagonist (aprepitant, approved since 2003 for the prevention of vomiting induced by chemotherapy) has been successfully tested in patients with refractory CP. Several clinical trials have since been conducted confirming the efficacy of aprepitant in CP – e.g., due to T-cell lymphoma or drug-induced. Additional NKR-1 antagonists are currently in development and are being clinically tested in CP [15]. Very useful information can be found on the website of the Competence Center Chronic Pruritus of the University Hospital Münster in Germany [16].

Literature:

- Ständer S, et al: S2k guideline chronic pruritus. J Deutsch Dermatol Ges 2012; 10(Suppl 4): S1-S27.

- Cohen KR, et al: Pruritus in the elderly. Pharmacy and Therapeutics 2012; 37: 227-239.

- Metz M, Ständer S: Chronic pruritus – pathogenesis, clinical aspects and treatment. J Europ Acad Dermatol Venereol 2010; 24: 1249-1260.

- Bigliardi P: Pruritus in the elderly: multidisciplinary approach is useful and worthwhile. Dermatology Practice 2014; 24(2): 10-16.

- Heyn G: Pruritus: help for constant itching. Pharmaceutical Journal Online 2009; 43 (www.pharmazeutische-zeitung.de/index.php?id=31398; accessed March 2015).

- Stand S: Pruritus. UNI-MED Verlag D-28323 Bremen 2008.

- Grundmann S, Ständer S: Chronic pruritus: clinics and treatment. Ann Dermatol 2011; 23: 1-11.

- Ständer S, et al: Assessment of pruritus – current standards and implications for practice. Dermatologist 2012; 63: 521-531.

- Ständer S, et al: Pruritus assessment in clinical trials: consensus recommendations from the International Forum for the Study of Itch (IFSI) special interest group scoring itch in clinical trials. Acta Derm Venereol 2013; 93: 509-514.

- Reich A, Szepietowski JC: Pruritus intensity assessment: challenge for clinicians. Expert Rev Dermatol 2013; 8: 291-299.

- Weisshaar E, et al: Questionnaires to assess chronic itch: a consensus paper of the special interest group of the International Forum for the Study of Itch. Acta Derm Venereol 2012; 92: 493-496.

- Blome C, et al: Measuring patient-relevant benefits in pruritus treatment: development and validation of a specific outcomes tool. Br J Dermatol 2009; 161: 1143-1148.

- Finlay A, Khan G: Dermatology Life Quality Index (DLQI) – a simple practical measure for routine clinical use. Clin Exp Dermatol 1994; 19: 210-216.

- Eberlein B, et al: Adjuvant treatment of atopic eczema: assessment of an emollient containing N-palmitoylethanolamine (ATOPA study). J Eur Acad Dernatol Venereol 2008; 22: 73-82.

- Lotts T, Ständer S: Reserach in practice: Substance P antagonism in chronic pruritus. J Deutsch Dermatol Ges 2014; 12: 557-559.

- Competence Center Chronic Pruritus of Münster University Hospital: http://klinikum.uni-muenster.de/index.php?id=kompetenzzentrum_pruritus.

HAUSARZT PRAXIS 2015; 10(10): 12-14