Dermatoses in the genital area are not always infectious in nature. It is important to distinguish inflammatory dermatoses from malignant changes (e.g. erythroplasia as a manifestation of Bowen’s disease). Contact eczema of irritant and allergic origin occurs relatively frequently in the genital area. Atopic and seborrheic eczema are also found. Diagnosis of vulvar lichen ruber is indicated by reticular white (Wickham) streaks and livid gray-brown margins. Hypertrophic papules must be differentiated from condylomas or malignant changes. On the glans penis, lichen ruber may also manifest with a whitish reticular pattern, polygonal papules, or anular plaques. The typical scaling may often be absent in psoriasis of the genital area. Common causative drugs of fixed drug exanthema include cotrimoxazole, NSAIDs, tetracyclines, and barbiturates. Typical signs of lichen sclerosus are hemorrhages in the sclerosed areas, sometimes with hemorrhagic blisters. In balanitis/vulvitis plasmacellularis zoon, mottled, orange-red erythema is typically found.

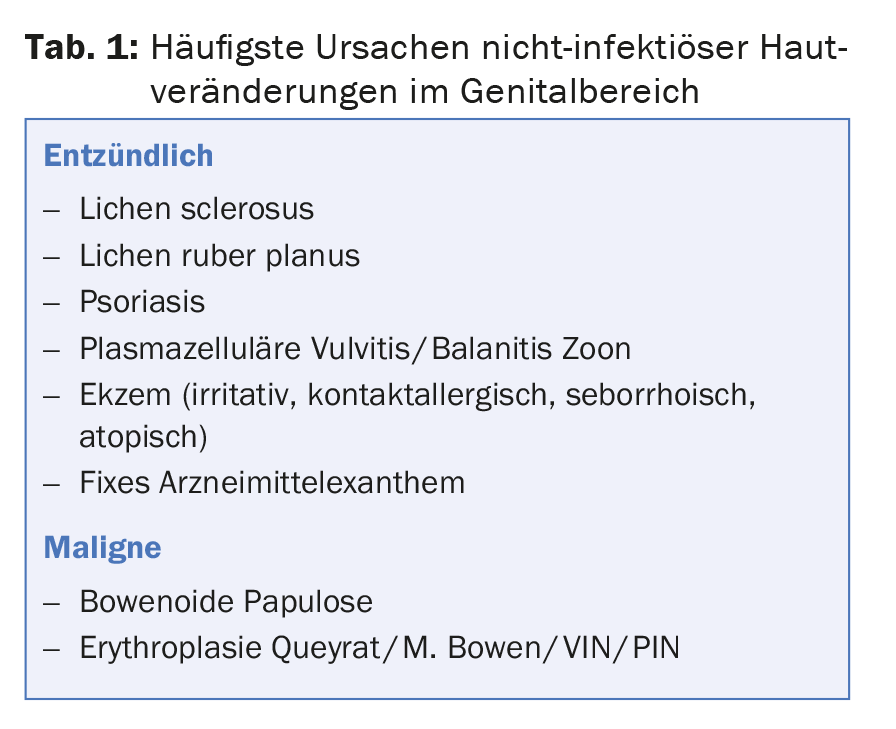

Inflammatory changes in the genital area do not have to be caused by an infection, whether sexually transmitted or not. Nearly 50% of baloposthitides and an even larger proportion of vulvovaginites are of noninfectious etiology. In principle, all dermatoses can also manifest in the genital area. Therefore, in this article we will limit ourselves to more common and important diagnoses. The spectrum ranges from inflammatory dermatoses to malignant changes (Tab. 1).

Eczema

In the genital area, irritant and allergic contact eczema are of particular importance. In addition, atopic and seborrheic eczema can also be observed in the genital area. The typical eczema morphology may not be apparent due to the absence of scaling. Uniform pruriginous erythema is common (Fig. 1), with occasional edema. Lichenification and excoriations may occur in the area of the labia majores. Atopy should be looked for in the history and by prick test. A detailed history regarding possible mechanical irritation (e.g., prolonged and repeated sexual intercourse/masturbation) is important, as is a search for contact toxins including previous therapy. Condoms (latex, rubber accelerators) and their coatings (spermicides, fragrances, local anesthetics) and lubricants are the most common allergen sources. Patients often conceal genitally applied care products, lubricants or other aids out of a sense of shame, which is why the topic must be specifically addressed.

Ammonia in urine has an irritant effect and can therefore cause irritant eczema if there is frequent and prolonged skin contact, which is why incontinence problems should also be asked about.

In addition to eliminating causative factors as much as possible, mild cleansing, moisturizing skin care and, if necessary, topical steroids can be used for treatment. It should be borne in mind that cream bases are more likely to be perceived as burning in the mucous membrane area than ointments. Also, cream bases contain more preservatives, which can cause irritation or secondary contact allergy.

Patients should always be brought into a therapeutic equilibrium with regard to their hygiene habits, in which lack of cleansing must be avoided as well as over-care with frequent use of irritant detergents. This is especially essential if pretreatments have already taken place. Inappropriate or overly intensive therapies, often with rapid change of preparations if there is no response, can lead to perpetuation of the eczema, which is why in these situations any therapy may have to be temporarily paused.

Lichen ruber

The spectrum of symptoms of vulvar lichen ruber, ranging from itching and burning with discharge to the absence of subjective symptoms, is as varied as the clinic. Erosive changes are the most common. Clues to the diagnosis are reticular white (Wickham) streaking and livid-gray-brown marginal areas (Fig. 2) . The rarer hypertrophic papules are more difficult to differentiate from condylomas or malignant changes. If there is no clear clinical evidence with polygonal papules, nail changes or involvement of the oral mucosa on the remaining integument, a biopsy to confirm the diagnosis should be discussed.

In men, lichen ruber on the glans penis may also manifest with a whitish reticular pattern, polygonal papules, and often anular plaques (Fig. 3) . Therapy depends on the overall picture, although lesions in the genital area can be treated primarily with highly potent topical steroids.

Psoriasis

Psoriatic plaques can be observed in the genital area as on the rest of the skin, but often the typical scaling is absent (Fig. 4). The sharp border of the foci, the symmetrical distribution, the involvement of the rima ani and, of course, psoriatic changes on the rest of the integument may be indicative. Maceration and fissures can cause itching, burning and pain. Genital psoriasis leads to a deterioration in quality of life, especially with regard to sexuality.

Therapeutic options include topical steroids, vitamin D analogs, and calcineurin inhibitors. Irritation should be avoided.

Fixed drug exanthema

Systemic medications can typically cause a picture of fixed drug exanthema with livid macules, bullae, or erosions in the genital area (Fig. 5). The most common causative drugs are cotrimoxazole, NSAIDs, tetracyclines, and barbiturates.

Lichen sclerosus

In lichen sclerosus, the pathogenesis is unclear; autoimmune factors may play a role. Subjective symptoms include itching and dyspareunia. Skin lesions include whitish discoloration and sclerosis. A typical clinical sign is hemorrhages in the sclerosed areas (Fig. 6), occasionally with hemorrhagic blisters. Phimosis or strictures may occur, necessitating surgical intervention.

Therapeutically, high-potency local steroids are primarily used. Because lichen sclerosus is a facultative precancerous condition, regular follow-up should be performed with regard to the development of squamous cell carcinoma. Patients must be informed to consult the physician if keratotic nodules appear, as a biopsy should then be performed.

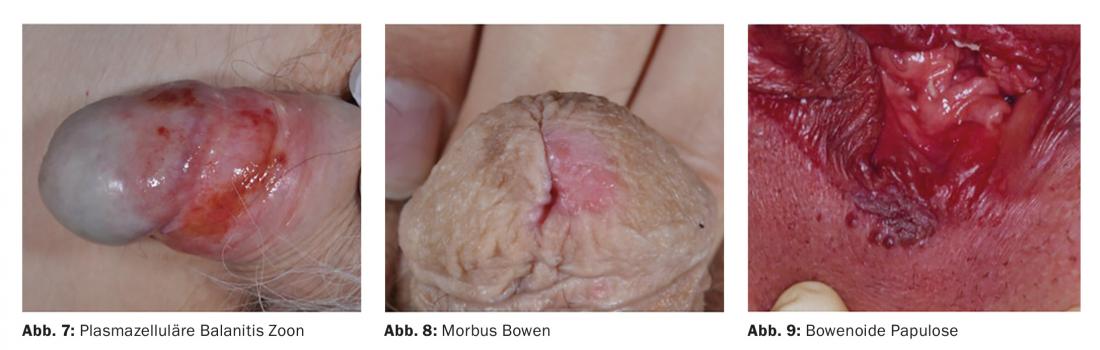

Balanitis/Vulvitis plasmacellularis Zoon

Balanitis chronica circumscripta plasmacellularis benigna was first described by Zoon in 1952. Clinically, mottled, orange-red (“cayenne pepper-like”) erythema is found (Fig. 7). The term “balanitis zoon” distracts from the fact that similar changes can also occur on the vulva, nasal and pharyngeal mucosa. The term idiopathic lymphoplasmacytic mucositis/dermatitis has also been proposed for these zoonotic changes.

Here, the plasma cell infiltrate fits the hypothesized irritative genesis. Therefore, the treatment is also primarily disinfecting and drying. Topical steroids and calcineurin inhibitors may be considered if persistent.

Malignant changes

Erythroplasia as a manifestation of Bowen’s disease (Fig. 8) on the glans penis may pose a diagnostic problem in differentiating it from inflammatory changes. In analogy to corresponding vulvar changes in women (vulvar intraepithelial neoplasia, VIN), this is also referred to as penile intraepithelial neoplasia (PIN). Persistent findings should therefore be biopsied to detect (pre)malignant processes. In erythroplasia queyrat, red, velvety, sharply demarcated areas are found. Whitish plaques, keratoses, and induration suggest possible transition to spinocellular carcinoma. Bowenoid papulosis (Fig. 9) is characterized by brownish papules, which should be distinguished from condylomata acuminata. Depending on the extent of the findings, treatment options for premalignant changes include 5-fluorouracil 5% cream, imiquimod 5% cream, cryotherapy, photodynamic therapy, LASER ablation, radiotherapy, and excision.

Acknowledgments: Christian Greis, MD, Dermatologisches Ambulatorium STZ, for assistance in illustrating the article.

Further reading:

- Andreassi L, Bilenchi R: Non-infectious inflammatory genital lesions. Clin Dermatol 2014; 32: 307-314.

- Edwards SK, et al: 2014 UK national guideline on the management of vulval conditions. Int J STD AIDS 2015; 26: 611-624.

- O’Connell TX, et al: Non-neoplastic epithelial disorders of the vulva. Am Fam Physician 2008; 77: 321-326.

- Borelli S, Lautenschlager S: Differential diagnosis and management of balanitis. Dermatologist 2015; 66: 6-11.

- Edwards S, et al: 2013 European guideline for the management of balanoposthitis.Int J STD AIDS 2014; 25: 615-626.

- Fistarol SK, Itin PH: Diagnosis and treatment of lichen sclerosus. An update. Am J Clin Dermatol 2013; 14: 27-47.

DERMATOLOGIE PRAXIS 2015; 25(4): 15-18