Studies suggest that Active Surveillance is a treatment option for tumors with low risk of progression (low-risk tumors). The treatment team should work with the patient to determine treatment strategies based on existing guidelines and current evidence. In Active Surveillance, patient follow-up and regular monitoring are critical factors in the treatment strategy. More and more prostate cancers are being diagnosed on the basis of PSA measurements. About 90% of these tumors are localized. A large proportion of diagnosed tumors do not pose a risk to the affected patients; the risk of morbidity from intervention is higher for these patients than the risk of morbidity from the tumor.

According to current guidelines (S3 Guideline DGU, EAU Guideline on Prostate Cancer), there are several alternative options for the treatment of localized low-risk prostate cancer: radical prostatectomy, local radiotherapy, active surveillance and, depending on age, the concept of watchful waiting. Active Surveillance (AS) means the close monitoring of individuals diagnosed with a disease during its course. AS must be distinguished from Watchful Waiting. This includes symptomatic treatment strategies of a disease in its course without the goal of transferring patients to curative therapy, for example because of advanced age and/or severe comorbidities. AS should also be distinguished from clinical/public health surveillance – in which the aim is to collect, analyze and interpret health-related data in relation to specific populations [1].

Active surveillance in low-risk cancers.

Recent analysis and interpretation of cancer treatments for selected oncologic conditions in men have pursued the goal of avoiding overtreatment with invasive treatment options. In particular, criteria have been developed for prostate and testicular cancers that result in no immediate or no treatment. For both entities, treatment guidelines specify that in addition to established treatment options (prostatectomy, radiotherapy, medical tumor therapy, hormone ablation, orchiectomy), AS is available for low-risk disease tumors as another primary treatment option [2,3]. The decision for or against AS as a treatment strategy is determined by the classification of the tumor as “low-risk”.

Using prostate carcinoma as an example, the practical difficulties in the choice of possible treatment will be demonstrated below. That cancer classification is still – despite many years of research – characterized by a very heterogeneous practice is shown in recent studies [4–11]. For example, the rate of patients with a low-risk tumor decreased from 60% in 2004 to 27% in 2013 – based on the revised definitions of low-risk tumors [12].

Epidemiology and etiology

Prostate cancer is the most common cancer in men in Switzerland [13]. There is a difference in incidence among different populations: in the USA, dark-skinned people are more frequently affected than whites, and the latter more frequently than Asians. This suggests a genetic predisposition to carcinoma development [9]. It is likely that genetic predisposition is also influenced and modified by sociodemographic factors [14–16]. For example, the incidence of prostate cancer increases among Asians who immigrate to the United States. The incidence of clinically nonsignificant prostate cancer is comparable throughout the world, but differences exist for clinically relevant prostate cancer. Men with a first-degree relative with prostate cancer have twice the risk of also developing prostate cancer. If several first-degree relatives have the disease, the risk increases to 5 to 11 times [10,17].

The majority of all prostate cancers probably arise due to multiple genetic polymorphisms [10]. Testosterone is not currently considered a precancerous agent, but likely plays a role as a tumor promoter in already progressive tumors. Dietary components affect prostate cancer in many ways [18]. Animal proteins appear to favor the risk of developing advanced prostate cancer. The trace element selenium has been discussed for some time with regard to a possible protective benefit. However, the SELECT trial was unable to demonstrate such a benefit and was therefore terminated prematurely in 2008. Tobacco smoking at the time of initial diagnosis increases the risk of advanced tumor, recurrence (38 vs. 26%), and death due to carcinoma (15.3 vs. 9.6/1000 person-years) [15]. Metabolic syndrome also increases the risk of prostate cancer. A correlation between prostate cancer risk and alcohol consumption could not be shown so far.

High percentage of overtreatments

For more than 30 years, radical prostatectomy has been considered the standard of care for the curative treatment of prostate cancer; approximately 70% of patients under the age of 70 undergo prostatectomy [8,12]. This strategy is followed under the assumption that the patient is cured after the intervention. These considerations must increasingly be put into perspective: In an estimated 30% of men who have undergone surgery, PSA progression occurs during the course of the operation. Some patients have tumors that do not necessarily require intervention; these patients would not die from the tumor even without surgery or radiation. However, the possibilities to estimate the individual tumor biology are still limited today. Therefore, the treatment team and patients often choose the path of intervention, often out of concern that the tumor may progress to a stage that can no longer be curatively treated due to rapid progression.

Regular active observation of patients with clinically unremarkable low-risk carcinomas suitable for AS may prevent therapy-related morbidities (erectile dysfunction, incontinence, surgery-related and radiation-related complications, etc.) and thus overtreatment and is considered safe in this setting. The psychological burden of the patient and partner under the guidance of an experienced urologist is also considered appropriate [6,18]. The ERSPC study showed a 54% rate of overtreatment. Sparing these men the morbidities of interventional therapy is the purpose of AS [5].

Criteria for Active Surveillance

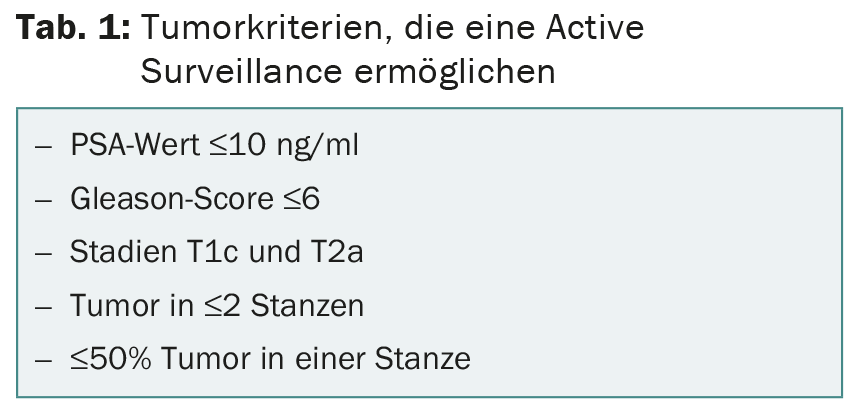

The current S3 guideline on early detection, diagnosis, and treatment of the various stages of prostate cancer includes AS as a treatment strategy for defined low-risk carcinomas that meet certain criteria (Table 1).

The guideline defines the following relevant decision criteria:

- Patients with localized prostate cancer who are candidates for local curative treatment should be informed not only about treatment procedures such as radical prostatectomy, radiotherapy, and brachytherapy, but also about AS.

- In patients with localized prostate cancer who are candidates for curative treatment, the adverse effects and treatment consequences of radical prostatectomy, percutaneous radiotherapy, and brachytherapy should be weighed against the risk of delayed treatment in the case of an AS strategy.

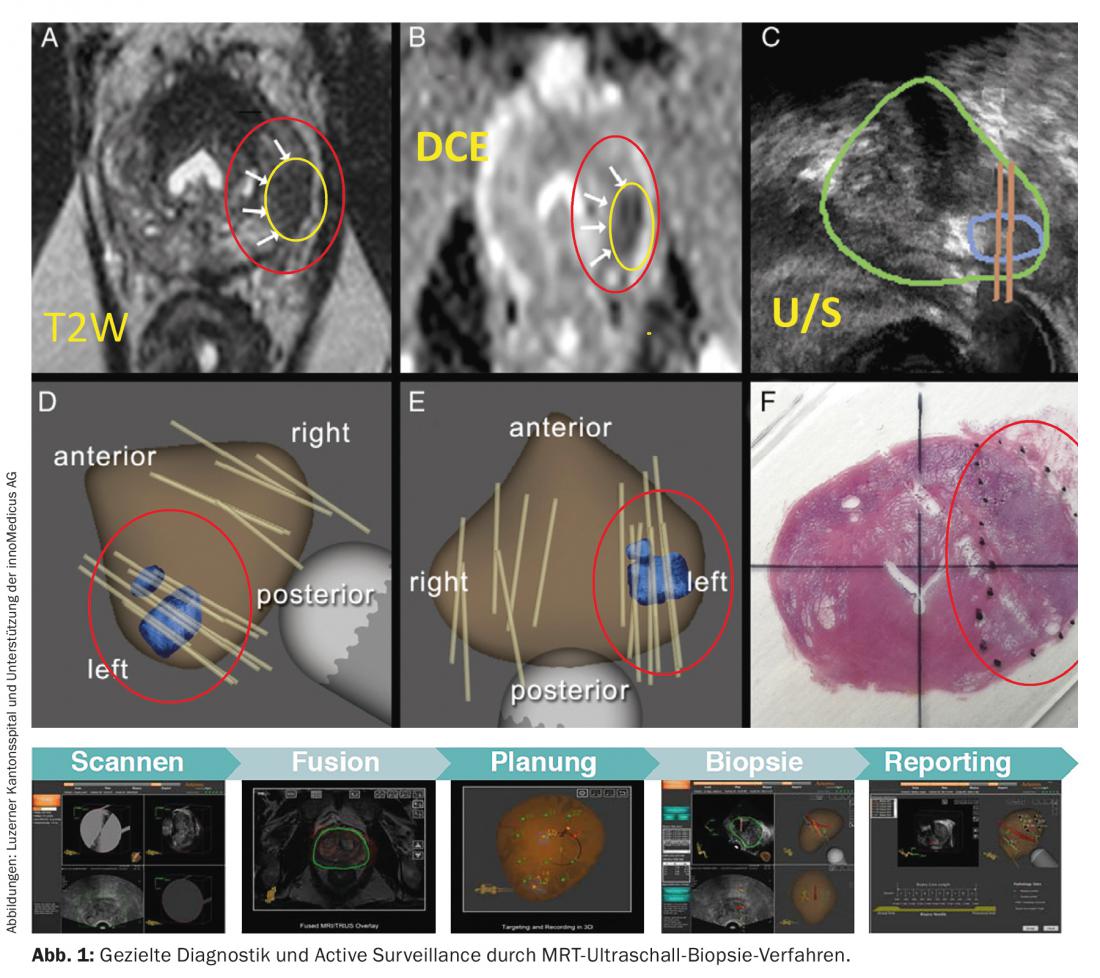

- The tumor should be monitored by PSA determination and digital rectal examination every three months for the first two years after diagnosis. If the PSA value remains stable, it should be checked every six months thereafter. Biopsies should be taken every 12-18 months. Currently, new methods are being investigated to increase the informative value of prostate biopsies (Fig. 1).

- The AS should be abandoned if the PSA doubling time is reduced to less than three years or the malignancy grade worsens to a Gleason score >6.

The extent to which treatment should be adapted in the individual course (e.g. radical prostatectomy or local radiation) depends directly on the individual dynamics of the cancer. Every patient is informed about all treatment options and is offered a procedure that enables him or her to live out the remaining years of his or her life without therapy-related impairments and with a high quality of life. Certified oncology centers demonstrably help ensure quality of care.

Conclusion for practice

- Currently, first-time baseline PSA testing is recommended in Switzerland between the ages of 40 and 45 years.

- If the PSA level is <1 ng/ml, PSA testing is recommended every three years, every two years for PSA ≥1 to <2 ng/ml, and annually for PSA ≥2 to <3 ng/ml . The patient must be informed in detail in advance.

- Excessive PSA measurements provoke the diagnosis of an increasing number of prostate carcinomas that would otherwise have remained undetected for a lifetime given age constellation, comorbidities, and/or favorable tumor biology for patients.

- Approximately 90% of patients diagnosed in recent years have localized prostate cancer.

- Studies suggest that AS is a therapeutic option for tumors with low risk of progression (low-risk tumors). Patients should be educated about all treatment options.

- Based on existing guidelines and current evidence, the treatment team (primary care physicians, urologists, radiation oncologists, oncologists) must work with the patient and family to determine and follow up on treatment strategies, especially in the case of possible AS.

- The Swiss Society of Urology has created an Active Surveillance database (SIP-CAS) to continuously secure and expand the evidence base.

Literature:

- WHO, Public health surveillance, 2015. www.who.int/topics/public_health_surveillance/en/.

- Kollmannsberger C, et al: Patterns of relapse in patients with clinical stage I testicular cancer managed with active surveillance. J Clin Oncol 2015; 33(1): 51-57.

- Coursey Moreno C, et al: Testicular tumors: what radiologists need to know-differential diagnosis, staging, and management. Radiographics 2015; 35(2): 400-415.

- Loeb S, et al: Active Surveillance for Prostate Cancer: A Systematic Review of Clinicopathologic Variables and Biomarkers for Risk Stratification. European Urology 2015; 67(4): 619-626.

- Klotz L: Active Surveillance for Prostate Cancer: Debate over the Application, Not the Concept. European Urology 2015 Jan 24. doi: 10.1016/j.eururo.2015.01.007. [Epub ahead of print]

- Bellardita L, et al: How Does Active Surveillance for Prostate Cancer Affect Quality of Life? A Systematic Review. European Urology 2015; 67(4): 637-645.

- Bangma CH, et al: Active Surveillance for Low-risk Prostate Cancer: Developments to Date. European Urology 2015; 67(4): 646-648.

- Saman DM, et al: A review of the current epidemiology and treatment options for prostate cancer. Dis Mon 2014; 60(4): 150-154.

- Helfand BT, Catalona WJ: The epidemiology and clinical implications of genetic variation in prostate cancer. Urol Clin North Am 2014; 41(2): 277-297.

- Eeles R, et al: The genetic epidemiology of prostate cancer and its clinical implications. Nat Rev Urol 2014; 11(1): 18-31.

- Berman DM, Epstein J: When is prostate cancer really cancer? Urol Clin North Am 2014; 41(2): 339-346.

- Huland H, Graefen M: Changing Trends in Surgical Management of Prostate Cancer: The End of Overtreatment? Eur Urol 2015 Feb 27. doi: 10.1016/j.eururo. 2015.02.020. [Epub ahead of print]

- Swiss Federal Statistical Office, 2015. www.bfs.admin.ch/bfs/portal/de/index/themen/14/02/05/key/01/02.html.

- Kasperzyk JL, et al: Watchful waiting and quality of life among prostate cancer survivors in the Physicians’ Health Study. J Urol 2011; 186(5): 1862-1867.

- Kenfield SA, et al: Smoking and prostate cancer survival and recurrence. JAMA 2011; 305(24): 2548-2555.

- Kenfield SA, et al: Physical activity and survival after prostate cancer diagnosis in the health professionals follow-up study. J Clin Oncol 2011; 29(6): 726-732.

- Bratt O: Hereditary prostate cancer: clinical aspects. J Urol 2002; 168(3): 906-913.

- Masko EM, et al: The relationship between nutrition and prostate cancer: is more always better? Eur Urol 2013; 63(5): 810-820.

InFo ONCOLOGY & HEMATOLOGY 2015; 3(5): 8-11.