The American Heart Association conference in Chicago drew attention primarily for two long-awaited study updates. At this point, the most important results from the IMPROVE-IT and DAPT studies will be examined again in more detail. How should the data be classified and what practical relevance do they have?

(ag) What is certain is that lowering LDL cholesterol is a mainstay of cardiovascular prevention. The evidence comes mainly from studies with statins. These showed a reduction in morbidity and mortality (high-dose statins reduced the rate of nonfatal cardiovascular events even more). To date, no other lipid-lowering therapy has been able to show clinical benefit as an adjunct to statins (fibrates, niacin, CETP inhibitors). The AHA/ACC guidelines, then, emphasize the relatively aggressive use of statins. IMPROVE-IT now aimed to show that the expected approximately 20% greater LDL reduction by ezetimibe (compared to statins) is also reflected in clinical outcomes. It is not only the largest study on lipid-lowering drugs, but also the longest. The key data: 18,144 patients with acute coronary syndrome (ACS) studied, recruited at 1158 centers in 39 countries, and followed up for an average of seven years. The question was to what extent high-risk ACS patients who already have low LDL cholesterol levels (50-125 mg/dl or 50-100 mg/dl if they were previously taking a statin) benefit from the addition of a non-statin to their standard statin treatment. The results can be considered positive.

Benefit confirmed – Safety good

Patients, who had to be at least 50 years old, were included in the study within 10 days of hospitalization (approximately 5000 due to STEMI, the remainder due to NSTEMI or unstable angina). They all had at least one feature that characterized them as high-risk patients for future cardiovascular events, such as a previous heart attack, diabetes, peripheral arterial occlusive disease or cerebrovascular disease, coronary artery disease in multiple arteries, or bypass surgery that had taken place. 9077 received the statin simvastatin (40 mg), and 9067 also took ezetimibe (10 mg), a so-called cholesterol resorption inhibitor.

Compared to the group receiving simvastatin and placebo alone, the study group receiving additional ezetimibe showed a 6.4% lower cardiovascular risk (primary endpoint composed of cardiovascular death, myocardial infarction, unstable angina with hospitalization, coronary revascularization, or stroke). The event rate was 34.7 vs. 32.7% in control and study groups, respectively (HR 0.936, CI 0.887-0.988, p=0.016). With regard to myocardial infarction and stroke, the probability was reduced by 14% each (significantly for the former, just not at all for the latter). Ezetimibe patients were also significantly less at risk for ischemic stroke (risk reduction of 21%, p=0.008). Regarding all-cause mortality, there was no difference between the groups.

The addition of ezetimibe did not lead to a relevant increase in side effects (e.g., muscle or gallbladder problems, cancer), and safety was consistently good.

The deeper, the better?

Thus, the addition of ezetimibe to simvastatin treatment reduces the likelihood of future cardiovascular problems such as myocardial infarction or stroke in high-risk ACS patients. Consequently, the additional LDL lowering provides a relevant benefit. Although the results are rather moderate in magnitude, given the good safety profile, some experts consider them sufficient to justify such therapy in clinical practice.

Dual therapy reduced LDL cholesterol to an average of approximately 54 mg/dl (compared with 69 mg/dl in the control group). It is noteworthy that patients who are already set low and have reached the clinically appropriate target LDL benefit from an even greater reduction. In everyday clinical practice, one would hardly think of treating such patients with an additional lipid-lowering drug. According to the authors, however, the principle “even lower is even better” applies here. This can be interpreted as confirmation of the results from the TIMI study, which showed better clinical results under a particularly potent statin that also lowered LDL levels more than regular-dose statins. It confirms the LDL hypothesis that lower LDL-C prevents cardiovascular events. Future guidelines could refer to this result.

Critics noted that a lot has changed since the start of the IMRPOVE-IT study and that simvastatin 40 mg is no longer widely used in practice (because US guidelines recommend higher-dose statins). According to this opinion, it would have been more interesting to test the ezetimibe addition with stronger statins.

DAPT – What came out?

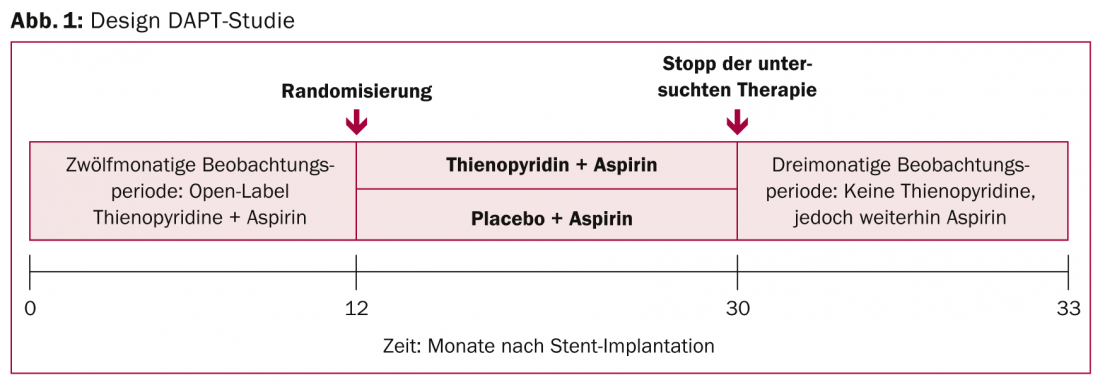

The second study that was eagerly awaited was the DAPT study (Fig. 1). It tested prolonged dual platelet inhibition in patients with coronary artery disease and deployed drug-eluting stent (DES). To be clear, the 30-month dual antiplatelet treatment (aspirin plus clopidogrel or prasugrel) produced significantly fewer blood clots in the stents and fewer myocardial infarctions than the corresponding shorter treatment (12 months plus 18 months of aspirin + placebo). These results go beyond current clinical practice: the US recommendations advise only 12 months of dual platelet inhibition after DES implantation, whereas the European recommendations even advise six to a maximum of 12 months of dual platelet inhibition.

9961 patients were randomized and followed for approximately three years (33 months). Specifically, with prolonged therapy (n=5020), the risk of so-called in-stent thrombosis was reduced by more than half after 30 months: In the study group, the rate of stent thrombosis, the primary endpoint, was 0.4% (vs. 1.4%, HR 0.29, CI 0.17-0.48, p<0.001). The co-primary endpoint consisting of relevant cardiovascular or cerebrovascular adverse events also showed a significant 29 percent difference in favor of the 30-month treatment variant. An important component of this, the rate of myocardial infarction, was 2.1% (vs. 4.1%, HR 0.47, CI 0.37-0.61, p<0.001) and was thus also reduced by half. The benefit in terms of in-stent thrombosis and myocardial infarction spanned all drug combinations, newer and older stents , and all risk groups. The benefit outweighed the risk of prolonged therapy, at least in the primary analysis: Although there was a significantly higher incidence of moderate to severe bleeding (primary safety endpoint: 2.5 vs. 1.6%), the rate of fatal outcomes was low in both groups and showed no significant differences.

Surprising mortality increase

The 30-month administration did not reduce all-cause mortality or stroke rates. On the contrary, a secondary analysis that included data after therapy cessation (after 33 months) showed a 0.8% increase in all-cause mortality for the study group (apparently due to trauma and cancer rather than cardiovascular causes). This difference is significant and was completely unexpected. Together with the increased bleeding rates, it clouded the otherwise good results. The study authors suggest that there were differences in recruitment among the study groups. Individuals with previously diagnosed cancer may have been distributed differently. Given the surprising result, they undertook a meta-analysis [1] of many large clinical trials that had also investigated dual platelet inhibition (with varying durations of therapy). No difference in all-cause or noncardiovascular mortality was found for the longer treatment duration compared with aspirin alone or shorter treatment. Therefore, they are currently assuming a single finding.

Important result with limitations

While it was previously clear that dual platelet inhibition was absolutely essential in prevention for all of these patients – after all, a blood clot, whether in the stent or in other blood vessels, is one of the most dangerous risks after DES placement. However, the fact that the benefits continue beyond the standard one-year duration has never been confirmed in such a large and well-powered study. On the one hand, dual platelet inhibition over a longer period of time may thus be considered in certain patients. The selection of eligible subjects is central (the study excluded patients with major bleeding before or one year after stenting/dual antiplatelet therapy). Interestingly, there seems to be a kind of rebound phenomenon: after discontinuation of dual antiplatelet therapy, the ischemic risk is increased for about three months [2], which is why the option of ongoing, even lifelong dual antiplatelet therapy for certain high-risk patients was discussed at the congress.

On the other hand, the increased bleeding rate must be considered in any case. The study also tested its hypothesis, as mentioned, only in patients in whom it was clear that they tolerated dual antiplatelet therapy well for more than one year. Moreover, the results cannot be generalized (only certain types of stents and antiplatelet agents were tested and not compared with each other).

The study was published in parallel in the New England Journal of Medicine [3].

Source: American Heart Association (AHA) 2014 Scientific Sessions, November 15-19, 2014, Chicago.

Literature:

- Elmariah S, et al: Extended duration dual antiplatelet therapy and mortality. The Lancet. Published Online: 16 November 2014.

- Garratt KN, et al: Circulation 2014 Nov 16. pii: CIRCULATIONAHA.114.013570 [Epub ahead of print].

- Mauri L, et al: N Engl J Med 2014; 371: 2155-2166.

CARDIOVASC 2015; 14(1): 36-38