Treatments for chronic diseases, most of which are complex, account for a large share of primary care consultations and total health care costs. “Chronic disease management” poses complex challenges for everyone: practitioners, patients and their social environment. Chronically ill people often also suffer from serious, but sometimes hidden, psychological comorbidities.

Psychological comorbidities can put a strain on the doctor-patient relationship and affect the success of treatment. Consideration of psychological comorbidities, on the other hand, can fertilize the physician-patient relationship. Especially for psychologically stressed patients, a good rapport is central. It may have a decisive effect on treatment compliance/adherence and thus on the success of treatment.

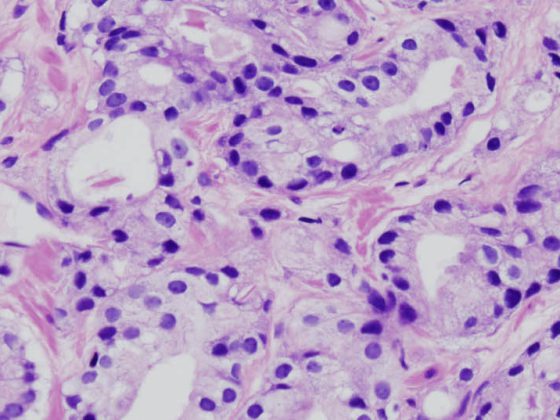

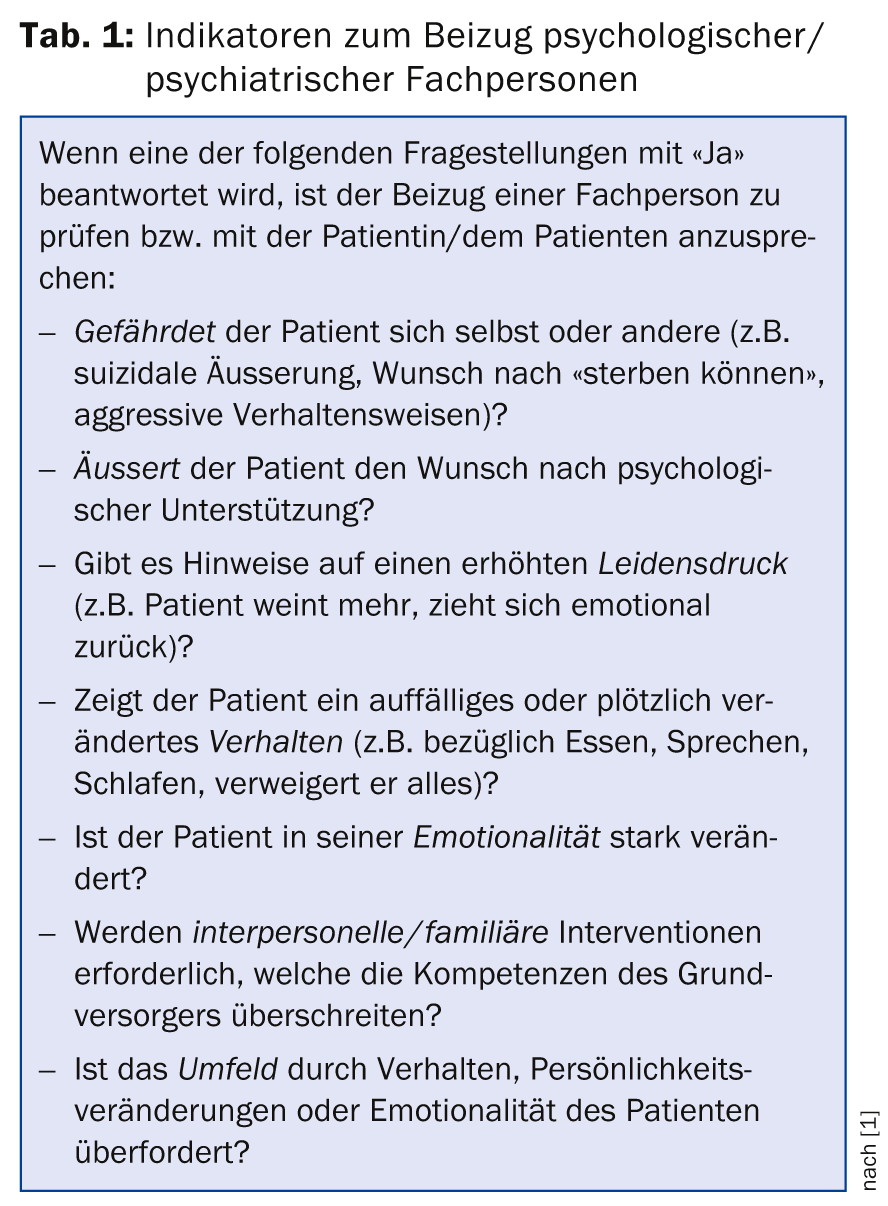

Mental illness is the most common cause of disability in new disability cases among 25- to 44-year-olds. Depression is seen as a leading cause of the global burden of disease and related to suicides and coronary heart disease. From an economic and social perspective, it is therefore important to identify mental (co)morbidities at an early stage and, if necessary, to provide qualified treatment (table 1).

Multiple psychosocial stresses

People with a chronic illness are often challenged on many levels. Physical impairments such as disability or pain are only the most obvious. It is not uncommon for only them to be presented to the primary care physician. In addition, however, there are almost always other stress factors. Restriction or loss of the ability to work, for example, can be a personal insult and a threat to self-esteem, bring about the loss of important social relationships and financial problems, and thus become a burden for the whole family. As a result, the affected person not infrequently suffers from additional feelings of guilt. The unfortunately still widespread stigmatization of mental health problems contributes in turn to the burden of disease. Overall, it must be assumed that one third of all patients in family practices have (comorbid) mental symptomatology.

Recognizing mental health problems

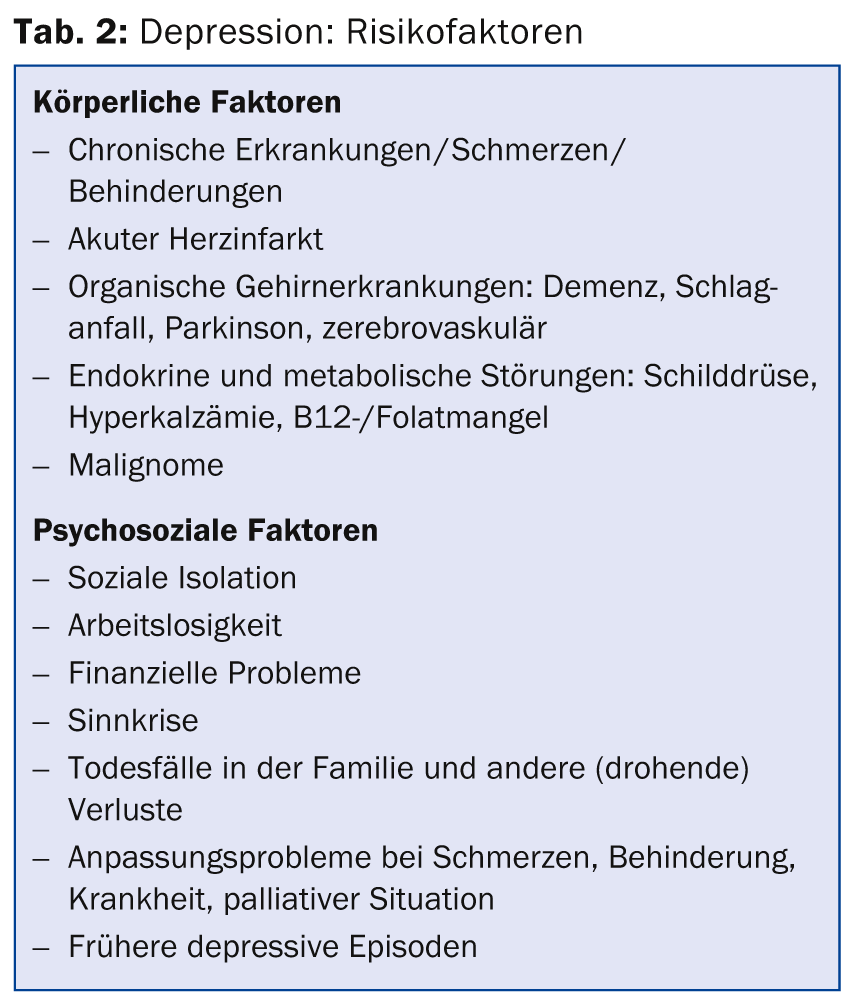

To identify a (comorbid) mental health problem, risk factors and symptoms can be considered and appropriate checklists can be used. For the very common depression, for example, risk factors are listed in Table 2 .

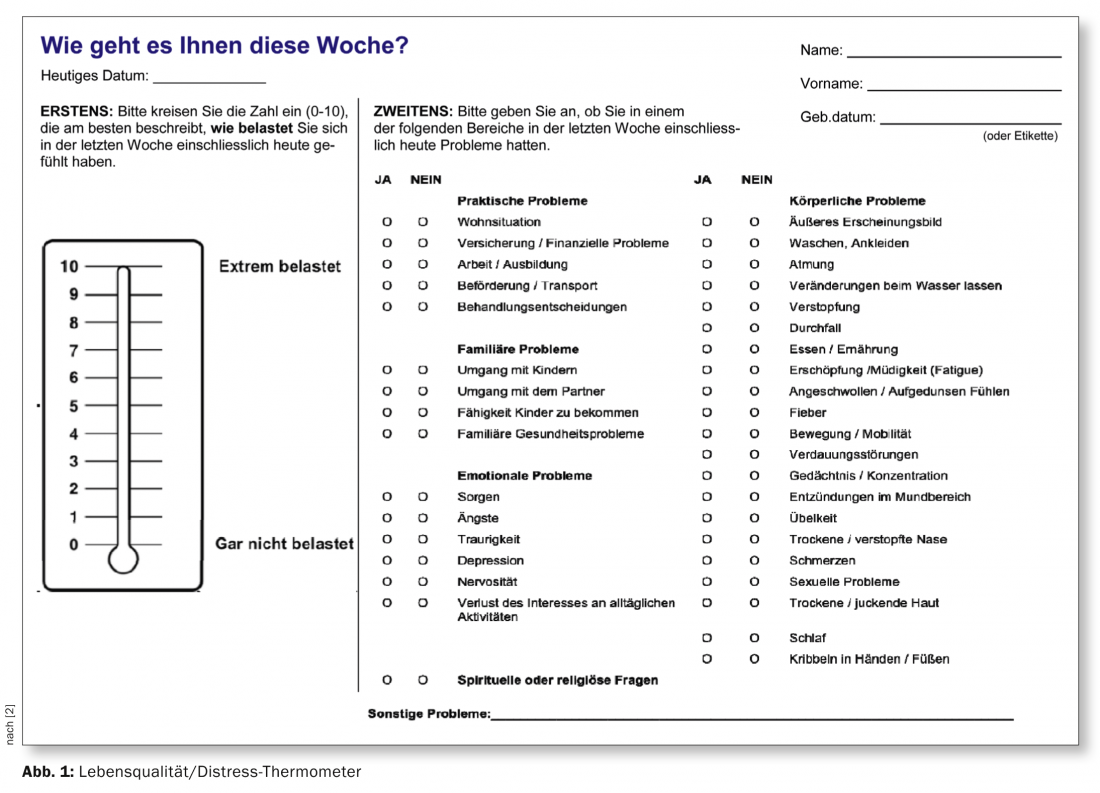

The “Distress Thermometer” was developed in the psycho-oncological field for the rapid assessment of the subjective severity of a problem (Fig. 1, download for free use [3]). This very efficient tool is also suitable for other stress situations and diseases. By means of a single cross on the visual-analog scale, the patient’s stress is reliably recorded. Often a value of five or higher is interpreted as an indication for a more in-depth evaluation by a specialist. If necessary, the second part can be used to break down the load. For example, having the patient fill out the sheet in the waiting room before the consultation gives the practitioner a quick overview of the person’s bio-psycho-social situation. The sheet is also suitable for relatives.

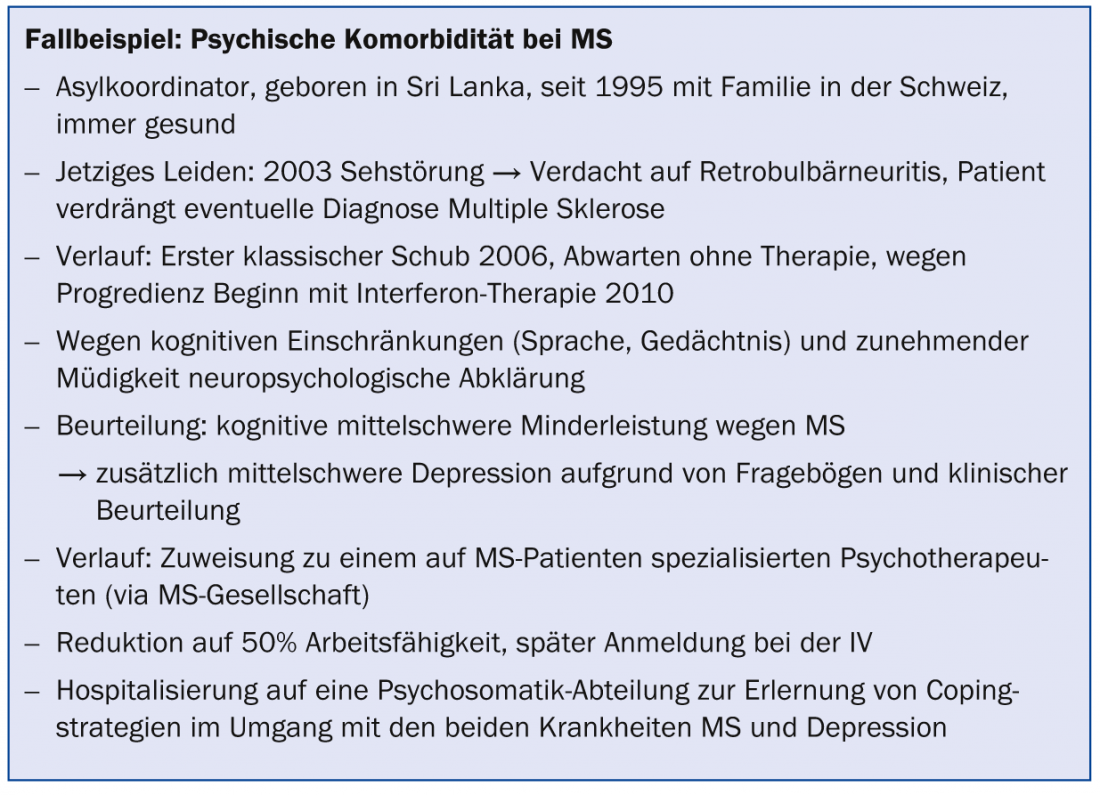

The case example in the box is intended to illustrate the problem of mental comorbidities once again using an everyday situation in practice.

Depression education

Finally, the clarification of a common misconception: A part of the population still believes that depression is not a “real” disease. Those affected, as well as those around them, think that you just have to try harder, that you are lazy, that it’s your own fault, etc. But it is true that depression can affect anyone, just like the flu. And depression is treatable, as are many other mental illnesses. Such clarification can already provide relief for those affected as well as their relatives and pave the way for further clarification.

Literature:

- BAG and GDK (eds.): Empfehlungen für die allgemeine Palliative Care zum Beizug von Fachpersonen aus der Psychiatrie/Psychotherapie 2014.

- Mehnert A, et al: The German version of the NCCN Distress Thermometer. Journal of Psychiatry, Psychology and Psychotherapy 2006; 54(3): 213-223.

- www.npg-rsp.ch/fileadmin/npg-rsp/DistressThermometer.docx.

- Alder J, et al: Position paper “Psychological work with the chronically physically ill”. Bern/Zurich: Verein chronischkrank.ch 2011. Available: www.chronischkrank.ch/files/Positionspapier-Psychologische-Arbeit-mit-chronisch-koerperlich-Kranken_01.pdf.

- Alder J, Künzler A, Strittmatter R: One disease rarely comes alone. In physical chronic diseases, the psyche must not be forgotten. Care Management 2011; 4(1): 12-14. Available: www.care-management.emh.ch/d/show_pdf.asp?art=2011-01-005.

- Baer N, et al: Depression in Switzerland. Data on epidemiology, treatment and socio-occupational integration (Obsan Report 56). Neuchâtel: Swiss Health Observatory 2013.

- Ferrari AJ, et al: Burden of Depressive Disorders by Country, Sex, Age, and Year: Findings from the Global Burden of Disease Study 2010. PLoS Med 2013; 10(11): e1001547. doi:10.1371/journal.pmed.1001547.

- Fröhlich S, Rousselot A, Künzler A: Psychosocial aspects of chronic diseases and their influence on treatment. Swiss Medical Forum 2013; 13: 206-209. Available: www.medicalforum.ch/docs/smf/2013/10/de/smf-01425.pdf.

- Jackson JC, et al: Depression, post-traumatic stress disorder, and functional disability in survivors of critical illness in the BRAIN-ICU study: a longitudinal cohort study. The Lancet Respiratory Medicine 2014; 2: 369-379.

- Künzler A, Mamié S, Schürer C: Diagnosis shock: cancer. Help for the soul – A guidebook for professionals, affected persons and relatives. Heidelberg: Springer 2012.

- Künzler A, Znoj H, Bargetzi M: Cancer patients are different – What is often noticeable and sometimes difficult. Swiss Medical Forum 2010; 10: 344-347. Available: www.medicalforum.ch/docs/smf/archiv/de/2010/2010-19/2010-19-154.pdf.

- Lorig K, et al: Healthy and active living with chronic disease. Haslbeck J, Kickbusch I (eds.). Zurich: Careum 2012.

- Steurer-Stey C: Prevention and health promotion for the chronically ill. Care Management 2009; 2: 13-15.

Dr. phil. hum. Alfred Künzler

CONCLUSION FOR PRACTICE

- Recognize: Watch for hints and changes in mood and engagement. Consider psychological backgrounds in the case of unclear pain, sleep disturbances, loss of appetite, fatigue or restlessness – because the prevalence of mental illness is high.

- If suspicious: ask empathetically.

- Act: Access a network, such as.

- Health leagues with div. Support services

- chronischkrank.ch (Links)

- outpatient psychotherapists (psychologists, psychiatrists)

- Inpatient psychosomatic departments

Because a chronic disease is always multi-faceted.

HAUSARZT PRAXIS 2014; 9(12): 33-35