In a broad overview of non-scarring alopecias, Prof. Ralph M. Trüeb, MD, Wallisellen, Switzerland, addressed the successes of previous therapies and discussed the current evidence base at the 96th Annual Meeting of the SGDV. Especially in alopecia areata, there are hardly any systematic data on the efficacy of the different types of treatment. In addition, the optimal patient management was also addressed and finally the speaker gave tips on how to deal with “difficult” hair patients.

(ag) Non-scarring alopecias account for over 95% of all alopecias, making them by far the most common form of hair loss. They are due to disturbances in the normal course of the hair growth cycle and are basically reversible and treatable (albeit with limitations related to the indication and effectiveness of therapy). In addition to knowledge of the biology of hair growth, the causes and their treatment, empathetic patient management is also crucial for the success of the therapy. The professional-technical level is thus decisively complemented and completed by the communicative level. “Communicative competence is not a talent, but can be learned. It requires an honest interest both in the problem of hair loss (content level) and in the patient himself (relationship level),” says Prof. Ralph M. Trüeb, MD, Wallisellen. “Communication also includes accurate information about the disease, the medication, its effects and side effects. This can decisively improve compliance. Anyway, it must be said that non-compliance is more often due to a failure of the physician than of the patient!”

Measures to promote compliance include information, simplification of drug therapy, minimization of the potential for side effects, and selection of drug (combinations) with which the best and fastest effect can be expected for the specific indication. Visible success in therapy significantly increases motivation. Monitoring with reproducible progress documentation is also crucial in this regard.

The professional-technical level involves a therapy that is oriented towards diagnosis and pathophysiology – a treatment, in other words, that not only remains open to potentially concurrent causes of hair loss or comorbidities, but also considers the possibilities of synergistic combination treatment. External evidence must be reconciled with the patient’s own clinical experience.

Pathophysiology of non-scarring alopecias

In the course of his lecture, Prof. Trüeb addressed alopecia areata (mitotic arrest), androgenetic alopecia (shortening of the anagen phase) and seasonal hair change (synchronization phenomenon).

According to evidence-based medicine, minoxidil (topical) and finasteride (oral) are the only two drugs with proven efficacy in androgenetic alopecia. In addition, there are various other treatments with low or no systematic evidence [1]. In combination, some of these can nevertheless additionally improve the results of evidence-based medicines; the decisive factor is always the individualized approach to the patient: “Studies with large samples are not readily applicable to the individual case. Although they provide a statistically accurate result, it is not known to whom this applies. For everyday clinical practice, it is therefore advisable to integrate individual clinical expertise with the best available external evidence from systematic research. This integration necessarily includes patient preference,” he said.

In an own study in patients with alopecia, Prof. Trüeb could recently show that with the combination treatment of minoxidil and Pantovigar® (nutrient combination for hair) a statistically significantly higher proportion of patients achieved a normalized telogen rate (≤15%) than with minoxidil monotherapy (p=0.03). Low-level laser therapies or anti-inflammatory combination treatments may also show good complementary efficacy.

“You have to stay open to the individual case and always reassess the patient. If, for example, hair loss suddenly increases again under therapy in summer, one should think of the seasonality of hair loss: Using the telogen rates of 823 otherwise healthy women who complained of hair regrowth, we were able to demonstrate in 2009 that the proportion of hair in the telogen stage was greatest in summer. A second but less pronounced peak appeared in spring and telogen rates were lowest in winter [2]. This seasonal variation can cause confusion and influence results not only in practice but also in large clinical trials,” Prof. Trüeb explained.

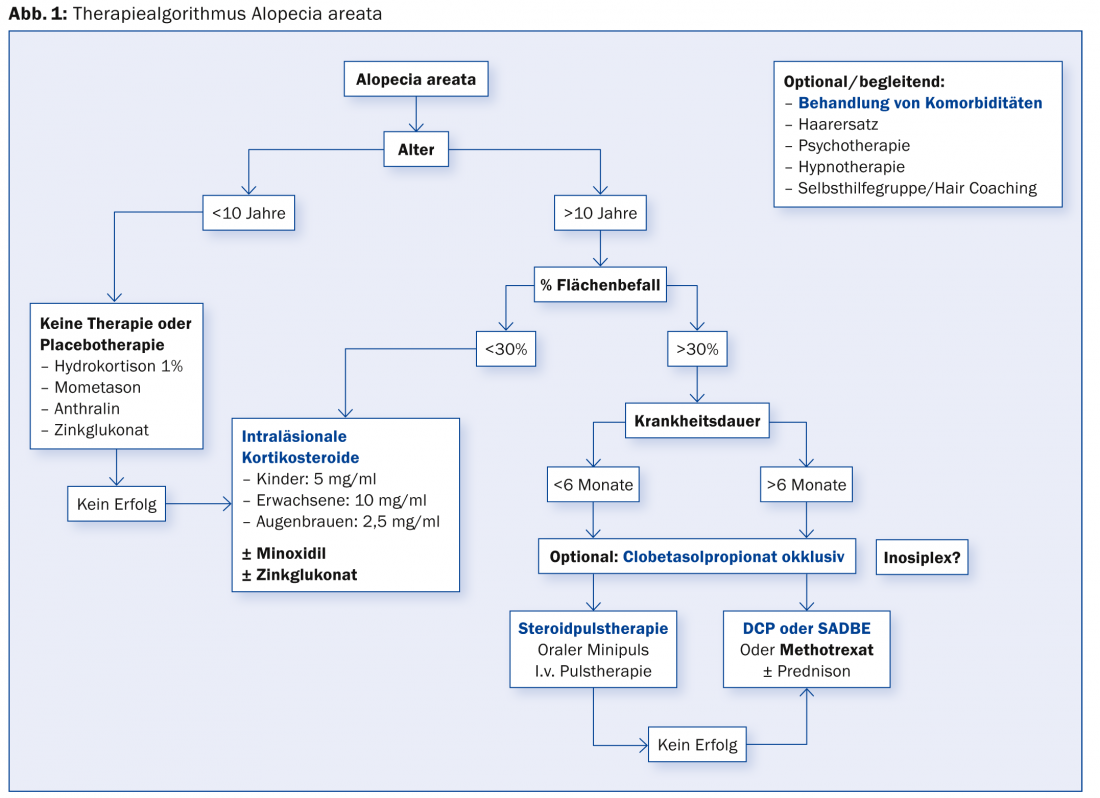

Alopecia areata

For this form of hair loss, a variety of intervention options are available, according to a Cochrane review, but none of them could show a statistically significant benefit over placebo. This is not least due to the fact that relatively few therapies against alopecia areata have been investigated in randomized controlled trials. In view of the poor data situation and the possibility of a spontaneous remission (especially in early stages), a therapy abandonment or the wearing of a wig should also be considered.

According to Prof. Trüeb, in the absence of evidence from good randomized controlled trials, therapeutic success in alopecia areata is measured by

- on the efficacy in the half-side test in alopecia totalis

- in a higher remission rate compared to the spontaneous course

- on a high safety profile with minimal toxicity

- on improving the quality of life.

The methods used include intralesional corticosteroids [3], clobetasol propionate occlusively [4], steroid powder therapy [5], diphenylcyclopropenone (DCP), or square acid dibutyl ester (SADBE) (Fig. 1). Intralesional corticosteroids are sometimes combined with minoxidil to improve the effect. Methotrexate alone or in combination with low-dose oral corticosteroids (with subsequent dose reduction) may also help certain patients [6].

“Difficult” hair patients

“So-called difficult hair patients are rather the exception and the causes are mostly due to previous negative experiences with physicians,” Prof. Trüeb explained. In addition, there are rare patients who actually show adjustment, hypochondriacal, body dysmorphic, and other personality disorders. The nocebo effect or noncompliance can also cause difficulties.

Adjustment disorders with depressive mood, anxious mood and behavioral impairment according to ICD-10 have certain consequences for treatment: In case of complaint about hair loss, the psychological distress of the affected person should be the indication for active therapy (regardless of the severity of hair loss and alopecia).

Personality disorders (anxious, negativistic, hysterical, paranoid) can lead to aggressive behavior on the part of the patient. In any case, this must be met with affirmation (any aggression on your part must be transformed into socially acceptable feelings). According to Prof. Trüeb, the solution is: compassion instead of aggressive impulses!

The nocebo effect is based on a certain expectation of the patient (unconsciously or consciously conditioned to it). An exciting study in this regard [7] was able to show that significantly more patients complained of sexual dysfunction when taking finasteride if they were informed about it beforehand than those who were not. The side effects complained of in the nocebo effect are highly psychosomatic in origin, occurring significantly more often in patients with specifically psychiatric disorders. “Overall, it can be said that the influence of the prescribing physician is of crucial importance, as the mediation of trust vs. doubt has a relevant impact on the success of therapy,” Prof. Trüeb said.

Psychogenic pseudoeffluvium

When women complain of hair loss that is perceived as pathological without showing objective signs, this is referred to as psychogenic pseudoeffluvium. “This patient represents the exception,” the speaker cautioned. The diagnosis proceeds via a process of exclusion:

- Clinical examination (no alopecia)

- Trichoscopy (no anisotrichosis)

- Hair calendar (normal number of hair fallen out)

- Trichogram (normal hair root pattern).

An underlying specific psychiatric disorder should be identified and possibly treated with psychotropic drugs. Otherwise, empathic patient management is especially important. “Basically, it’s important to remember: the stress that hair loss causes can be strong enough to increase hair loss,” Prof. Trüeb concluded his presentation.

Source: “Therapy of non-scarring alopecia,” lecture at the 96th Annual Meeting of the SGDV, September 4-6, 2014, Basel.

Literature:

- Blumeyer A, et al: Evidence-based (S3) guideline for the treatment of androgenetic alopecia in women and in men. J Dtsch Dermatol Ges 2011 Oct; 9 Suppl 6: S1-57.

- Kunz M, Seifert B, Trüeb RM: Seasonality of hair shedding in healthy women complaining of hair loss. Dermatology 2009; 219(2): 105-110.

- Abell E, Munro DD: Intralesional treatment of alopecia areata with triamcinolone acetonide by jet injector. Br J Dermatol 1973 Jan; 88(1): 55-59.

- Tosti A, et al: Clobetasol propionate 0.05% under occlusion in the treatment of alopecia totalis/universalis. J Am Acad Dermatol 2003 Jul; 49(1): 96-98.

- Nakajima T, Inui S, Itami S: Pulse corticosteroid therapy for alopecia areata: study of 139 patients. Dermatology 2007; 215(4): 320-324.

- Joly P: The use of methotrexate alone or in combination with low doses of oral corticosteroids in the treatment of alopecia totalis or universalis. J Am Acad Dermatol 2006 Oct; 55(4): 632-636.

- Mondaini N, et al: Finasteride 5 mg and sexual side effects: how many of these are related to a nocebo phenomenon? J Sex Med 2007 Nov; 4(6): 1708-1712.

DERMATOLOGIE PRAXIS 2014; 24(6): 46-48