From a medical-scientific point of view, an expert opinion can be regarded as a measuring instrument that is intended to provide accurate, reproducible and comprehensible results. It is important to be aware that very few validated examination concepts are available in psychiatric assessment. The medical performance evaluation remains a medical evaluation, with all the associated disadvantages. The psychiatric expert should have a thorough understanding of the client’s legal framework and requirements. It would also be desirable for the client to have a better understanding of the medical-scientific contexts, especially with regard to the depth of the examination and the time required on the part of the expert, which is the only way to ensure the quality of the clarification and fair treatment of the insured.

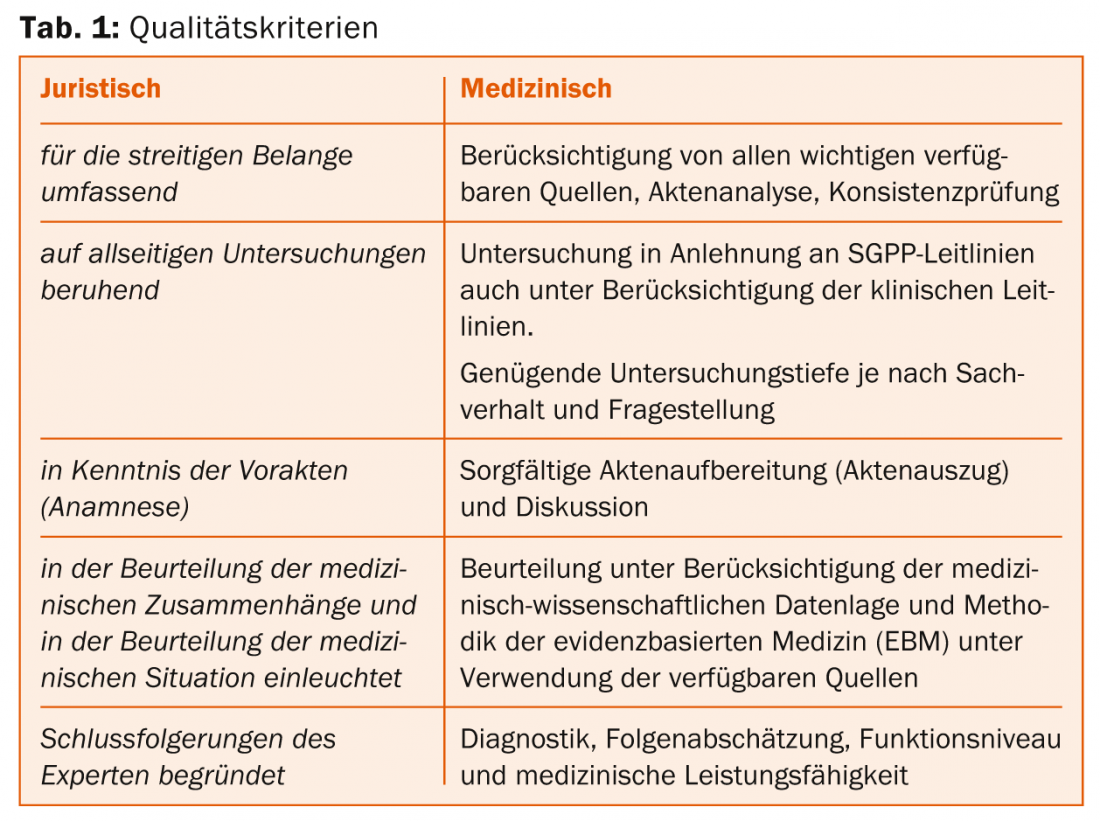

Medical opinions are often seen as bridging the gap between medicine on the one hand and the application of law on the other. Insurance medical reports are usually commissioned in unclear and/or at least partly complex and controversial cases in order to provide the legal practitioner with a usable basis for decision-making [1,2]. With regard to the evidentiary value of an expert opinion, from a lawyer’s point of view, it is decisive whether it is “is comprehensive for the matters at issue, is based on all-round investigation, also takes into account the complaints complained of, has been given with knowledge of the previous records (medical history), is plausible in its assessment of the medical context and in its evaluation of the medical situation, and whether the expert’s conclusions are well-founded” (Tab.1) [3].

The medical-scientific requirements for a psychiatric report, on the other hand, cannot be reduced solely to the criteria formulated by lawyers. Therefore, in order to evaluate the quality of the expert opinions, insurance carriers – in different constellations – involve their own medical experts (consulting physicians) [4]. Within the IV offices, these tasks are performed by regional medical services [5].

An appraisal can be viewed as a complex measurement tool [6] that ideally provides an accurate assessment, taking into account scientific evidence. Good measurement instruments are characterized by the fact that they provide the same results regardless of the investigator (objectivity) and that the results are reliable and replicable (reliability). Furthermore, a good scientific instrument should provide measurement data that actually represent the variable to be measured (validity, accuracy of content) [7]. It is worth mentioning in this context that with regard to the approach to the assessment (function of the measurement instrument), only a few validated criteria exist, mostly only in terms of expert opinion and clinical experience (level of evidence IV) [8,9].

Two studies on the quality of expert opinions in Switzerland are also worth mentioning: Ludwig found in 2006 that the structure of expert opinions was insufficient in 6%, the evidential value in 40%, the terminology in 5% and the technical content in 36% [10]. A detailed analysis of the Asim showed a result of 22.7% qualitatively insufficient, 48.4% qualitatively sufficient to good and 28.9% qualitatively very good expertises for 97 representative expertises regarding the overall evaluation. This clearly shows that there are major discrepancies in the quality of medical appraisals in Switzerland, and that with over 22% of inadequate appraisals, the deficiencies in the Swiss appraisal system identified in the preliminary studies and communicated in the media can be substantiated. The deficiencies of the expert opinions do not so much concern the formal structure, but are primarily based on superficial and incomplete findings and inadequate insurance medical discussion and substantiation of the conclusions [11].

In order to increase the quality (precision, reliability and reproducibility) of insurance psychiatric assessments, assessment guidelines were published by the SGPP in 2012 [12].

Understandably, the guidelines are only to be seen as decision-making and orientation aids in the sense of “action and decision corridors” as well as instructions for action [13]. Unlike guidelines, they are not binding and cannot answer all questions that arise in practice.

In the present paper, the authors would like to focus on some specific quality aspects, especially with regard to the depth of clarification and the associated time required to document the examination results.

Depth of examination and instruments from a medical and legal point of view

A psychiatric expert examination is usually the first time an explorand is seen by the psychiatric expert. In preparation, this often has some medical and administrative files available. In contrast to the therapeutic-clinical setting, where a clinical follow-up can provide essential information, only a cross-sectional survey is conducted in an assessment. The longitudinal section must then be extrapolated based on collected information and files.

In general, it is assumed that a psychiatric expert opinion includes a file analysis, an exploration incl. history taking as well as a clinical examination (combined with the use of additional procedures at the discretion of the reviewer) must be included. The clinical examination includes, in addition to behavioral observation incl. Description of the interactions with the explorant also the recording of the external appearance incl. the corresponding documentation of findings. Also relevant are the explorant’s language comprehension data [12]. It should also be taken into account that an exploration which has been carried out with the help of an interpreter may take longer due to the need for bidirectional translation [14].

In various federal court rulings it is stated that a “test-based assessment of psychopathology (e.g., according to the AMDP system) can generally only be regarded as supplementary, while the clinical examination with history taking, symptom recording and behavioral observation is decisive” [15,16]. In the respective judgement reasons the old evaluation guidelines were quoted [17], which mentioned a “schematic representation of the findings after certain scales” among other things after AMDP only in the sense of an auxiliary investigation. In contrast, current guidelines [12] recommend a status survey according to AMDP. The AMDP system is the most commonly used standardized examination procedure in German-speaking countries for recording psychopathological findings. Advantages lie in the uniform definition and in the possibility of documenting findings in a way that is comprehensible to others [18]. A “checklist”-like recording is not sufficient in this context. For the comparability and comprehensibility of the collected findings, a detailed descriptive documentation seems necessary. It must be recognizable what was examined, with what result, and in this sense, normal findings must also be recorded, if necessary. According to the AMDP manual, the time required for the standardized assessment of findings during the initial interview corresponds to 45 and 60 minutes, this without corresponding documentation [19].

It is also necessary to assess the personality, which is usually done in the sense of a longitudinal assessment, based on the collected medical history and information from others. The employment history can provide important clues (e.g., frequent job changes, training dropouts, job conflicts). If necessary, further psychometric tests, neuropsychological performance diagnostics [20] and, at the discretion of the experts, extended complaint validation procedures should also be used [21].

With regard to the expert assessment of functional capacity, the assessment of activities and abilities based on the mini-ICF APP has become widely accepted in recent years [22]. According to the test description (available at www.testzentrale.ch), the instrument takes about ten minutes to complete, which, however, contradicts the authors’ own clinical experience and is also viewed similarly by Ms. B. Muschalla, co-developer of the Mini-ICF APP (personal communication, August 21, 2014). It must be taken into account that in the course of the initial examination by an expert, the information regarding the social performance of the explorant must first be collected from various sources (self-report, external history, evaluation of files) and checked with regard to consistency. Mere marking of severity in each mini-ICF APP dimension-which may actually take less than ten minutes-seems insufficient. From the authors’ point of view, a “narrative explanation” of the individual dimensions against the background of the context and role requirements and taking into account the published anchor definitions is actually better suited to describe the resources or deficits than a pure “tick box” approach.

Duration of the examination varies

The case law in the field of social insurance assumes that the significance of a doctor’s report (and an expert opinion) does not depend on the duration of the examination, but on whether the examination report is complete in terms of content and conclusive in its results [23]. In the judgment I 1094/06 of November 14, 2007 [24], the Federal Supreme Court states that the time required for a psychiatric examination depends on the question and the psychopathology to be assessed and cannot generally be defined in a binding manner.

A disease with a clear manifestation of symptoms can often be diagnosed in a short period of time [25], while a high expenditure of time may be necessary in cases of suspected simulation, complex personality diagnosis, and suspected possible post-traumatic disorder. However, Foerster and Winckler clearly state that it may be necessary to examine the explorant on several days, depending on the research question. They also assume that a time commitment of less than two hours is not sufficient for a difficult personality diagnosis. In general, it is assumed that a short examination duration is associated with a risk of potential misjudgments. Traub [26] states that with regard to a forensic expert opinion (judgment 6P.40/2001 of September 14, 2001, E. 4d/dd), the Federal Supreme Court assumed that a careful expert assessment of a previously unknown person could hardly succeed within the framework of a one or two-hour examination, which – according to Traub – can also be applied mutatis mutandis to the insurance medical context. He holds that a twenty-minute examination is clearly insufficient for clinical analysis, history taking, symptom recording, and behavioral observation. Only if it is essentially a matter of assessing an established medical fact and new examinations would be superfluous, can a pure expert opinion on file also be of full probative value.

Depth of investigation in clinic and research

As an example, the examination procedures of the special consultation hours of the Psychiatric University Hospital Zurich (PUK) [27] and the University Hospital Zurich (USZ, Psychiatric Polyclinic) will be outlined here. A comparison between these clarifications and the assessment setting is appropriate, since these are initial contacts in each case and therapeutic measures are not initially in the foreground.

In the ADHD consultation of the PUK Zurich, an assessment is usually carried out in four appointments of 60 minutes each (240 minutes). In addition to taking a medical history and clinical examination, the specific test procedures (Wender Reimherr Interview [WRI], Symptom Check List 90-Revised, Wender Utah Rating Scale [WURS-k] and Attention Deficit/Hyperactivity Self-Report Scale [ADHS-SB]) are used. The administrative effort or the documentation of the findings and the reporting have not yet been taken into account (personal communication, Dr. med. A. Buadze, senior physician, 22.08.2014).

At the screening consultation for psychoses, the exploration takes about three to four hours (two appointments of 1.5-2 hours each); in addition, if indicated, a neuropsychological examination is performed, which takes about three hours (personal communication, Dr. med. C. Obermann, senior physician, 26.08.2014).

At the Trauma Consultation Center (PTSD) of the University Hospital Zurich [28], an assessment takes place at four appointments. There is an initial interview lasting approximately 1.5 hours and three additional sixty-minute interviews. This is a purely clinical assessment using test psychology instruments. No explicit assessment of performance is performed (personal communication, K. Hassanpour, MD, senior physician, 08/21/2014).

In the study by Suppiger et al. [29], which was conducted for the purpose of validating a diagnostic interview procedure in the clinical setting, the average interview duration was 106 minutes and a high interrater reliability of >89% was achieved.

The time required seems relatively high. It must also be taken into account that in the clinical setting, the special aspects typical of an expert opinion, such as a detailed occupational history, social history and a survey of the performance profile, were not collected, or only marginally.

Time required should not be underestimated

In summary, it can be assumed that detailed psychiatric diagnostic assessments in the clinical setting may well be in the range of three to four hours. It should be noted that special insurance medical aspects are not explicitly surveyed.

In the forensic psychiatric literature, it is assumed that the time required for an expert witness exploration can reach five to six hours or more [20]. Also in the already quoted Federal Court decision [30] it is mentioned that in general (in the area of criminal law) a time expenditure of about four to eight hours – in individual cases also longer – on at least two examination dates is to be expected.

Conclusions

Even though no absolute recommendation can be given with regard to the duration of the examination due to the available data, the authors assume, similar to Foerster and Winckler [25], that a higher probability of error must be expected if the examination is too superficial or too short. In the authors’ view, the obviously discrepant examination times in the field of criminal and social insurance assessments cannot be explained by medical science, but are due to the respective requirements of the client.

A comprehensive psychiatric examination lasting several hours, if possible spread over two or more appointments – which is common practice in the field of criminal law in Switzerland – is often a prerequisite for the preparation of a high-quality psychiatric report. However, this requires that the client provides the necessary (financial) resources. If the examination depth required from a medical point of view is not feasible due to the framework conditions defined by the client, this must be made transparent – including the possible implications for the reliability of the results.

The approach of the reviewer should follow the guidelines of the SGPP. In addition, the clinical guidelines of any professional societies should (at least) be taken into account with regard to the respective diseases or disorders. It is essential to provide detailed documentation that is comprehensible to other medical professionals and also to lawyers, using the terminology that is customary and precisely defined in the relevant specialist circles.

Characteristics for high time expenditure are among others multiple differential diagnoses of different ICD-10 categories documented in the files, diagnosis of a personality disorder as well as a neurotic, stress and somatoform disorder (especially in disputed cases), aggravation and simulation, the presence of observation materials, clarification of the connection between traumatic events and subsequent symptomatology, complex retrospective assessments and examinations with interpreters, as well as cases in which one or more preliminary reports already exist that need to be evaluated. These constellations can come into play completely independently of the status of the proceedings. From the authors’ point of view, it is not advisable to allow oneself to be forced into a corset due to the client’s time constraints, which no longer allows the required quality criteria to be met.

Michael Liebrenz, MD

Literature:

- Federal Act on the General Part of Social Insurance Law ATSG), Art. 43 and 44.

- Ordinance on Disability Insurance (IVV) Art. 69 para. 2.

- Federal Court decision 122 V 160 of 3.5.1996.

- Federal Court judgment 8C_400/2013 E. 5.1 of 31.7.2013.

- Federal Law on Disability Insurance (IVG) Art. 59.

- Deutsche Rentenversicherung Bund, Berlin (ed.): Sozialmedizinische Begutachtung für die gesetzliche Rentenversicherung – Inhaltsverzeichnis. Springer-Verlag Berlin, Heidelberg, New York 2011; 98-99.

- Linden M: Manual aspects of socio-medical assessment in mental disorders. The Rehabilitation 2014; 52(06): 412-422.

- Dittmann V, et al: Literature study as a basis for the development of evidence-based quality criteria for the assessment of mental disabilities. Bern: Federal Social Insurance Office BSV 2009.

- Ebner G, et al: Development of guidelines for the assessment of mental disabilities. Survey of the formal quality of psychiatric assessments. Bern: Federal Social Insurance Office BSV 2012.

- Ludwig CA: Expert opinion quality in accident insurance. Medical Communications 2006; 5-16.

- Stöhr S, et al: Expert opinion quality in Switzerland: results of a study. Staempfli Verlag Bern Social Law Days 2010; 218-238.

- Colomb E, et al: Quality guidelines for psychiatric assessments in the Federal Disability Insurance. Swiss Society of Psychiatry and Psychotherapy 2012. Available at: www.psychiatrie.ch.

- Develop a methodology for the development of best medical practice guidelines. Swiss Medical Journal 2003; 84(39): 2042-2044.

- Hadziabdic E: Working with interpreters: practical advice for use of an interpreter in healthcare. Int J Evid Based Healthc 2013; 11: 69-76.

- Federal Court decision 9C_391/2010 of 19.7.2010.

- Federal Court decision I 391/06 of 9. 08. 2006, E. 3.2.2.

- Guidelines of the Swiss Society for Insurance Psychiatry for the assessment of mental disorders. Swiss Medical Journal 2004; 85(20): 1048-1051.

- Rösler M, et al: 50 years of the AMDP system – A review. Journal of Psychiatry, Psychology and Psychotherapy 2012; 60(4): 269-280.

- AMDP: The AMDP system. Manual for the documentation of psychiatric findings. 8th revised ed. Hogrefe Göttingen 2006.

- Stevens A, Fabra M, Merten T: Guidance for the preparation of psychiatric reports. Med Sach 2009; 105: 100-106.

- Schleifer R, et al: (More) evidence from complaint validation procedures in IV procedures. SMF – Swiss Medical Forum 2014; 14(10): 214.

- Linden M, Baron S, Muschalla B: Mini-ICF-APP. Mini-ICF rating for activity and participation disorders in mental illness (manual and materials). Verlag Hans Huber, Hogrefe Bern 2009.

- Federal Court decision 9C_664/2009 of November 6, 2009.

- Federal Court decision I 1094/06 of November 14, 2007.

- Foerster K, Winckler P: Forensic psychiatric examination, in: Venzlaff U, Foerster K: Psychiatrische Begutachtung. 5th edition Urban & Fischer 2009.

- Traub A: On the evidential value of psychiatric reports under the aspect of the duration of the examination Judgment I 1094/06 of November 14, 2007 SZS 2008; 393.

- www.pukzh.ch/diagnose-behandlung/ambulantes-spezialangebot/spezialsprechstunden.

- www.psychiatrie.usz.ch/HEALTHPROFESSIONALS/ABKLAERUNGENUNDBEHANDLUNGEN/Seiten/PTDS.aspx.

- Suppiger A, et al: Reliability of the Diagnostic Interview in Mental Disorders (DIPS for DSM-IV-TR) under routine clinical conditions. Behavior Therapy 2008; 18(4): 237-244.

- Federal Court decision 6P.40/2001 of September 14, 2001, E. 4d/dd.

InFo NEUROLOGY & PSYCHIATRY 2014; 12(6): 30-34.