At the Swiss Family Docs conference at the Kongresshaus Zurich, the topic of diabetes was also addressed. In a comprehensive and detailed overview, Prof. Roger Lehmann, MD, Zurich, presented the study situation and the use of the new and old antidiabetic drugs in practice. Given the great dynamism in this field and the numerous developments and advances of recent years, such an inventory was necessary.

(ag) Type 2 diabetes is an interaction between chronic hyperglycemia, decreased beta cell function, and insulin resistance. The treatment strategy does not follow a rigid stepwise scheme – according to the new recommendations from the EASD/ADA/SGED position paper, the HbA1c target value is set (or calculated) flexibly according to various factors such as patient motivation, hypoglycemia risk, diabetes duration, life expectancy, important comorbidities, existing vascular complications, and resources.

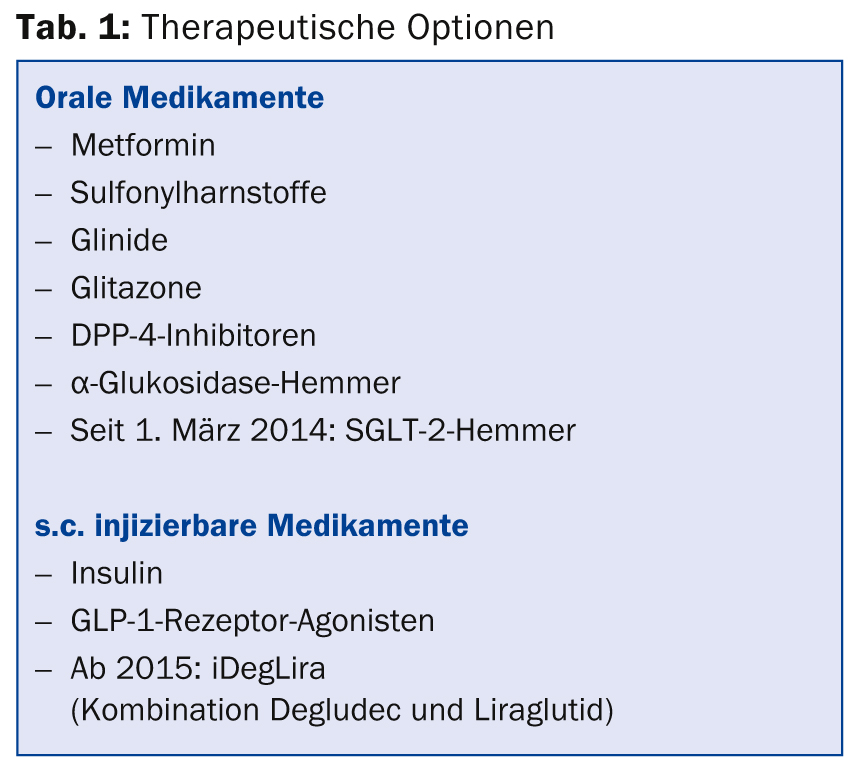

Anti-hyperglycemic therapy initially includes lifestyle measures (weight loss, healthy diet, increased physical activity). Furthermore, various drugs are used (Tab. 1) .

In principle, all drugs must be evaluated according to the following factors: Efficacy (HbA1c reduction), hypoglycemias, effect on weight, side effects, and cost. Metformin is the first-choice drug (combined with lifestyle), whose most relevant disadvantages are the size of the tablet and gastrointestinal side effects. After initial monotherapy, two-drug combinations of metformin and sulfonylureas, glitazones, DPP-4 inhibitors, GLP-1 receptor agonists, and insulin (usually basal insulin) are possible, as is the use of SGLT-2 inhibitors. The side effect profile is decisive for the choice here. “Regarding insulin, the incidence of hypoglycemia increases with increasing treatment duration in both type 1 and type 2 diabetes,” said Prof. Roger Lehmann, MD, UniversitySpital Zurich. Hypoglycemia is cardiovascularly significant as it has an association with increased mortality (e.g., after myocardial infarction) [1]. Drugs that do not cause hypoglycemia or weight gain are DPP-4 inhibitors, GLP-1 receptor agonists, and SGLT-2 inhibitors.

DPP-4 and GLP-1

Incretin-based therapies with DPP-4 inhibitors and GLP-1 receptor agonists have a growing role in diabetes therapy. Their use often follows metformin. The advantage of this treatment is the low to nonexistent hypoglycemia rate and weight neutrality (DPP-4) or weight loss (GLP-1). DPP-4 inhibitors also have no relevant side effects. Overall, HbA1c reduction of up to 1.5% is achieved with the agents. Possible disadvantages are partial nausea, high costs as well as the still low long-term experience.

Although head-to-head comparisons are not yet available, the HbA1c reduction of the available DPP-4 inhibitors (linagliptin, saxagliptin, sitagliptin, vildagliptin, alogliptin) appears to be of approximately the same magnitude.

A combination of DPP-4 inhibitors and GLP-1 agonists does not provide additional therapeutic benefit and therefore must not be used.

Comorbidity renal insufficiency

Renal insufficiency increases the risk of hypoglycemia. Metformin must be stopped in Switzerland at a GFR of <45 ml/min. When using sulfonylureas, caution should be exercised in the presence of comorbid renal insufficiency (especially glibenclamide and glimepiride). For DPP-4 inhibitors, dose adjustment is usually necessary (except for linagliptin [Trajenta®] [2]). GLP-1 receptor agonists should be avoided with a GFR <30 ml/min.

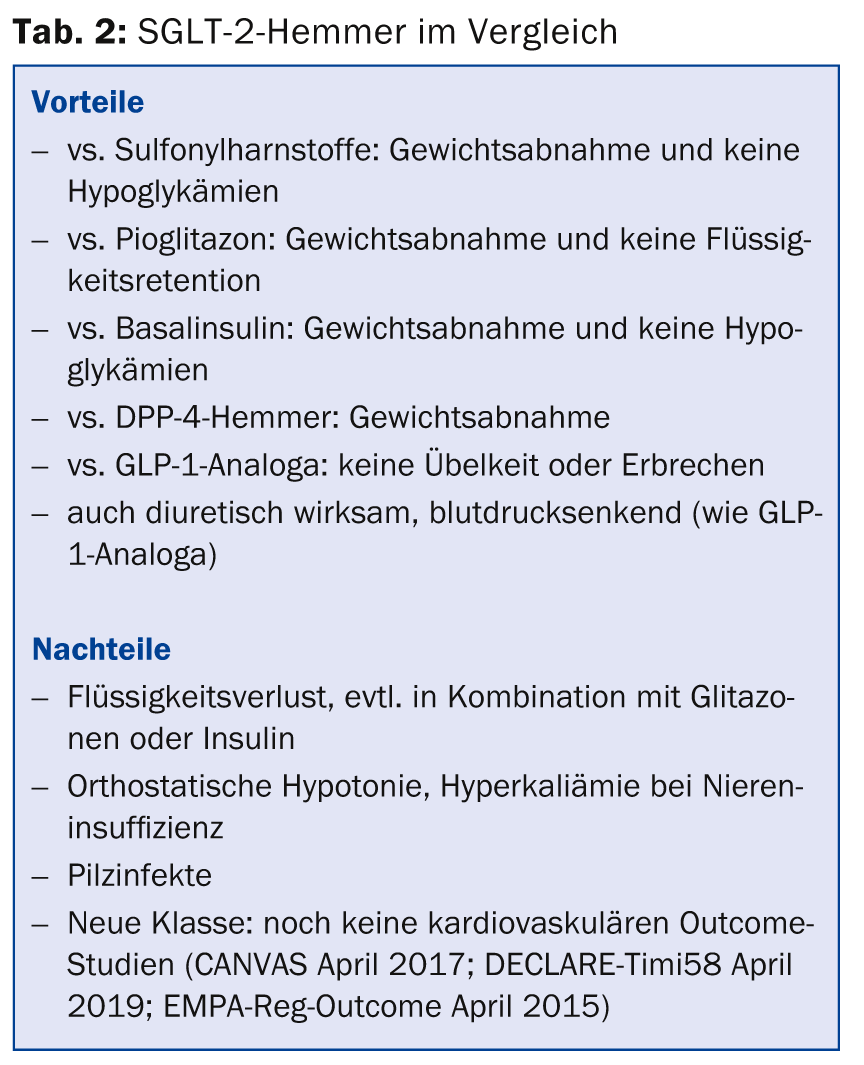

SGLT-2 inhibitors – insulin-independent effect

SGLT-2 inhibitors (canagliflozin since March 1, 2014) are also new on the market. They can be combined with all antidiabetic drugs. Their action is insulin-independent and they do not cause hypoglycemia, but tend to cause weight loss. What is the basis of their mechanism of action? While effective therapies are already available for several key organs involved in the regulation of plasma glucose, the kidney has been lacking until now. This shows increased glucose reabsorption in type 2 diabetes. SGLT-2 is responsible for a full 90% of total renal glucose reabsorption – if it is inhibited, such as with the newly approved SGLT-2 inhibitor canagliflozin, the excretion of glucose via the urine increases. Plasma glucose is reduced, hyperglycemia is addressed, and weight loss is supported. In a head-to-head comparison [3] with sitagliptin, canagliflozin at the 300-mg dose showed a greater reduction in HbA1c and weight loss that was significant by comparison. Side effects were comparable, but genital mycoses were more common with canagliflozin. The advantages and disadvantages of SGLT-2 inhibitors compared with other antidiabetic agents are summarized in Table 2.

Insulin

“Sooner or later, most patients with type 2 diabetes need insulin. Therapy usually starts with basal insulin, followed by the addition of prandial insulin,” says Prof. Lehmann.

Insulin degludec is a newly available basal insulin that reduces hypoglycemia with the same HbA1c reduction as insulin glargine [4].

From 2015, the combination of GLP-1 agonist (liraglutide) and new basal insulin (insulin degludec) will be available, called IDegLira. Expected properties of this combination are:

- All-day glycemic control

- Slow titration that minimizes hypoglycemia, weight gain, and nausea

- A single administration per day with only one pen.

Compared with insulin degludec [5], IDegLira in combination with metformin showed significantly greater HbA1c reduction and weight loss and 34% fewer hypoglycemias (despite 1.1% lower HbA1c). The incidence of nausea was comparably low in the two groups.

Security

According to current knowledge, cardiovascular safety (e.g., study on saxagliptin [6]) and safety with respect to cancer and pancreatitis [6,7] are given when using the new agents, i.e., there is no evidence of increased incidences under therapy. The only exception is SGLT-2 inhibitors, where data are currently lacking. Three cardiovascular outcome trials of GLP-1 agonists and the basal insulin degludec are currently ongoing (LEADER Oct 2015; EXSEL April 2018; DEVOTE Nov 2018).

Source: “State of the Art: Diabetes”, presentation at the Swiss Family Docs Conference, August 28-29, 2014, Zurich.

Literature:

- NICE-SUGAR Study Investigators: Intensive versus conventional glucose control in critically ill patients. N Engl J Med 2009 Mar 26; 360(13): 1283-1297.

- Graefe-Mody U, et al: Effect of renal impairment on the pharmacokinetics of the dipeptidyl peptidase-4 inhibitor linagliptin(*). Diabetes Obes Metab 2011 Oct; 13(10): 939-946.

- Schernthaner G, et al: Canagliflozin compared with sitagliptin for patients with type 2 diabetes who do not have adequate glycemic control with metformin plus sulfonylurea: a 52-week randomized trial. Diabetes Care 2013 Sep; 36(9): 2508-2515.

- Garber AJ, et al: Insulin degludec, an ultra-longacting basal insulin, versus insulin glargine in basal-bolus treatment with mealtime insulin aspart in type 2 diabetes (BEGIN Basal-Bolus Type 2): a phase 3, randomised, open-label, treat-to-target non-inferiority trial. Lancet 2012 Apr 21; 379(9825): 1498-1507.

- Buse JB, et al: Contribution of Liraglutide in the Fixed-Ratio Combination of Insulin Degludec and Liraglutide (IDegLira). Diabetes Care 2014 Aug 11. pii: DC_140785. [Epub ahead of print].

- Scirica BM, et al: Saxagliptin and cardiovascular outcomes in patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus. N Engl J Med 2013 Oct 3; 369(14): 1317-1326.

- Egan AG, et al: Pancreatic safety of incretin-based drugs – FDA and EMA assessment. N Engl J Med 2014 Feb 27; 370(9): 794-797.

HAUSARZT PRAXIS 2014; 9(10): 40-42