Arterial occlusive disease is a disease with multiple sites (coronary, cerebral, peripheral, and visceral). Cardiovascular risk factors must be treated aggressively even in the asymptomatic patient with PAOD. The pAVK is easy, fast and inexpensive to diagnose by ABI. When pAVD progresses in the symptomatic or asymptomatic patient, drug, interventional, or surgical therapies become necessary. Four modifiable risk factors are responsible for pAVD: smoking, diabetes, hypertension, and dyslipidemia.

Peripheral arterial disease (PAVD) affects 202 million people worldwide. That is almost five times as many as there are HIV-positive patients worldwide. There is no longer a difference in the prevalence of pAVD: borders, income, and standard of living no longer play a role in the incidence of disease. As one of the most common causes of morbidity and mortality, pAVD has thus assumed a pandemic character. This was the conclusion of a study published in the Lancet in October 2013 [1]. And there is a lot in there that confirms what we know so far, but also brings new insights that change the picture of PAOD.

A disease with multiple settings

My very esteemed former boss and teacher used to say, “In five years, medicine doubles its knowledge – and that’s a good thing, because it eliminates 50% of the errors.” Such a time seems to have come once again. Old knowledge is confirmed, but the previous picture of pAVK is shaken as some misconceptions are eliminated.

Atherosclerosis is a metastatic underlying disease with metastases to the brain, heart, and peripheral and visceral arteries. Unfortunately, the current terminology does not help to emphasize this clearly. Today, we speak of “coronary heart disease,” “cerebrovascular insufficiency,” “stroke,” “intermittent claudication,” “peripheral arterial circulatory disease,” etc. In a textbook published in 2002 [2], we have already proposed to stop this confusing and inaccurate terminology and instead to speak of a coronary arterial, a cerebral arterial, a peripheral arterial and a visceral arterial occlusive disease: a disease with multiple sites. Unfortunately, this did not catch on.

Secondary prophylaxis crucial

Today, many people still accept PAOD as a nuisance that should not be taken seriously. No wonder, because two thirds of the manifestly ill patients have no symptoms [3]! This also does not lead most people to the doctor, and the doctor will not become aware of it during a normal examination. One-third of patients have symptoms, but these are often superimposed on other causes of leg pain, usually arthritic or lumbar in nature.

Awareness of the need to aggressively treat cardiovascular risk factors even in the asymptomatic patient with PAOD does not take due precedence. Even in the manifest symptomatic patient, adequate secondary prophylaxis of atherosclerosis is less frequently performed than, for example, in the patient with a coronary manifestation: in pAVK patients, only 33% receive a beta-blocker, only 29% an ACE inhibitor, only 31% a statin, and in known diabetes, only 45% are in the recommended HbA1c-value of less than 7% [4]. The risk of critical ischemia or amputation is 1% per year, but the mortality risk is 5-15%, three to four times higher than in a comparison group of the same age [5].

What is the benefit of early diagnosis?

PAOD has emerged as an independent risk factor for cardiovascular morbidity and mortality. As a rule, it is easy, quick and inexpensive to diagnose: An ABI (ankle-brachial index) measurement as a fixed part of medical check-up examinations, similar to an ECG as a matter of course, would detect the majority of sufferers.

But what is the point of diagnosing pAVD early, when it is still asymptomatic? Exercise-induced leg pain reduces the productivity and overall health of sufferers. 50% of them have significant coronary involvement and 43% have significant cerebral involvement [6]. To not diagnose pAVD is to miss a preventive approach in these patients.

When pAVD progresses in the symptomatic or asymptomatic patient, drug, interventional, or surgical therapies become necessary to restore quality of life or prevent amputation. Earlier prevention can prevent this and is thus a contribution to saving health care costs.

But atherosclerosis does not metastasize only to the heart, brain, peripheral or visceral arteries. In addition, there is a risk of morbidity and mortality caused by the individual risk factors [7]: the risk of dilated angiopathy or the risk of developing tobacco-related neoplasms is increased. Patients with atherosclerosis also suffer

more frequently with chronic renal failure or dementia.

Modifiable risk factors

There are still essentially four modifiable risk factors responsible for PAOD:

- Smoking

- Diabetes

- Hypertension

- Dyslipidemia.

Old findings that have fortunately resulted in a few measures, but on the whole too few. The smoking ban or advertising ban for smoking products has not been enforced for long and not yet across the board, or is being undermined by clever campaigns.

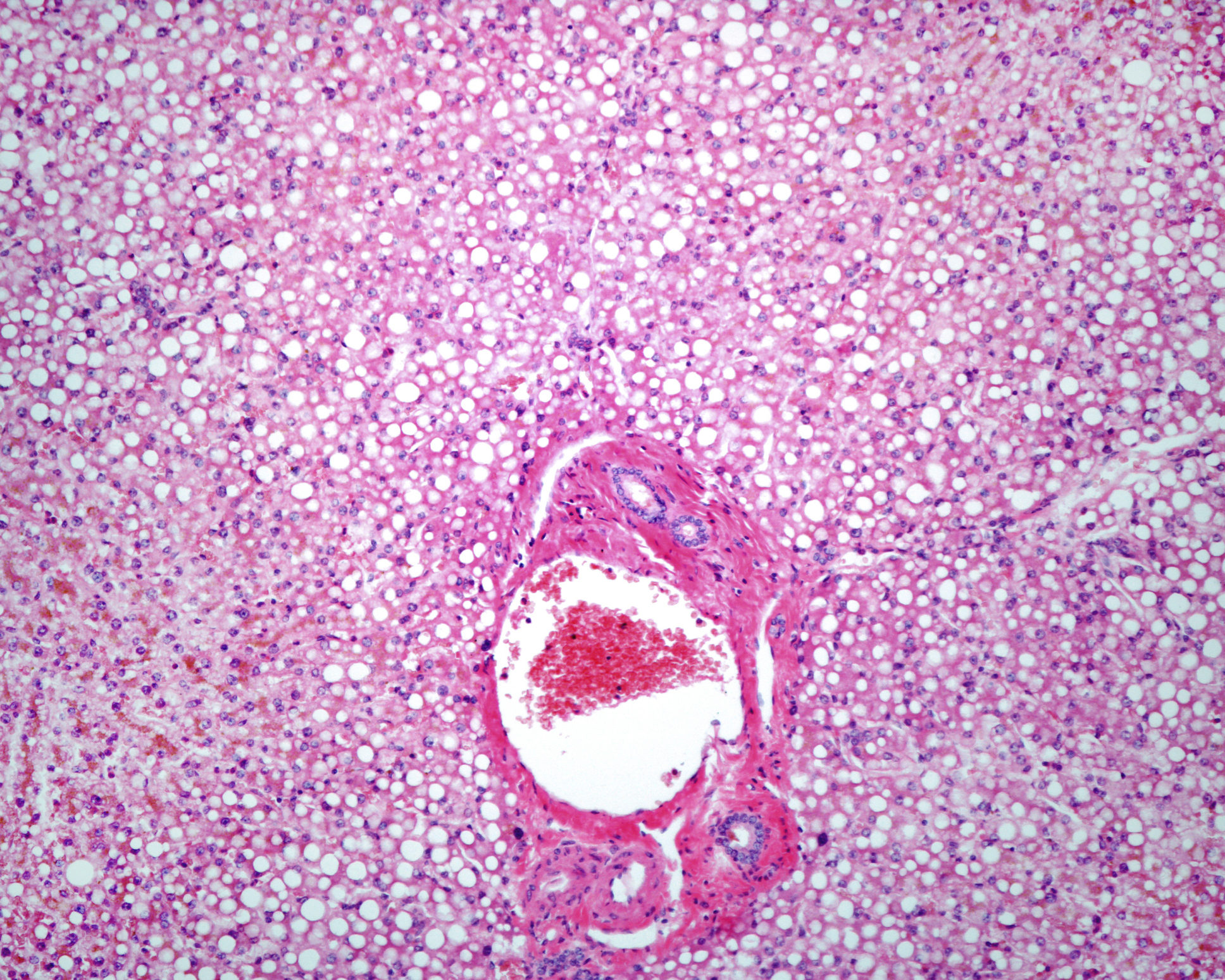

The incidence of diabetes mellitus will increase significantly in the coming years. Obesity caused by physical inactivity could be easily prevented by preventive measures such as sports and exercise programs [8]. In Germany alone, it is calculated that there will be 1.5 million more diabetics between the ages of 55 and 74 by 2030 compared to today [9]. 20% of diabetics over 40 years of age have manifest, usually asymptomatic, PAOD, which is an indicator of high amputation and cardiovascular risk. For the past ten years, the American Diabetes Association has recommended that all diabetics over the age of 50 be screened for possible PAOD [10].

Influence on incidence and prevalence

If it was previously assumed that men suffer from the disease more frequently than women, this must be counted among the errors that have just been eliminated: PAOD affects both sexes equally often in high-income countries, and in middle- and lower-income countries, women are even more frequently affected than men.

From 2000 to 2010, the incidence of pAVD increased by 23.5%. This increase will continue unless appropriate preventive measures are taken. High-income countries lack insight, low-income countries lack money.

However, a first approach must be to detect pAVD early and across the board. This will require raising awareness among all stakeholders, patients and physicians alike, as well as caregivers, relatives, health insurers, etc., that peripheral arterial disease is not a harmless evil, but a metastatic disease that has a significant, preventable cardiovascular morbidity and mortality risk even in asymptomatic patients.

Literature:

- Fowkes GR, et al: Comparison of global estimates of prevalence and risk factors for peripheral artery disease in 2000 and 2010: a systematic review and analysis. The Lancet 2013; 382: 1329-1340.

- Pilger E, et al: Arterielle Gefässerkrankungen, Standards in Klinik, Diagnostik und Therapie, Thieme Verlag 2002.

- Diehm C, et al: Prognostic value of a low post-exercise ankle brachial index as assessed by primary care physicians. Atherosclerosis 2011; 214: 364-372.

- Hirsch AT, et al: The PARTNERS Program. A national survey of peripheral arterial disease prevalence, awareness and ischemic risk. JAMA 2012; 286: 1317-1324.

- Criqui MH, et al: Mortality over a period of 10 years in patients with peripheral arterial disease. NEJM 1992; 326: 381-386.

- Marsico F, et al: Prevalence and severity of asymptomatic coronary and carotid artery disease in patients with lower limbs arterial disease. Atherosclerosis 2013; 228: 386-389.

- Paraskevas KI, et al: Patients with peripheral arterial disease, abdominal aortic aneurysms and carotid artery stenosis are at increased risk for developing lung and other cancers. Int Angiol 2012; 31: 404-405.

- Lindström J, et al: Sustained reduction in the incidence of type 2 diabetes by lifestyle intervention: follow-up of the Finnish Diabetes Prevention Study. Lancet 2006; 368: 1673-1679.

- Brinks R, et al: Prevalence of type 2 diabetes in Germany in 2040: estimates from an epidemiological model. European Journal of Epidemiology 2012; 27: 791-797.

- American Diabetes Association: Peripheral arterial disease in people with diabetes: Consensus statement. Diabetes Care 2003; 26: 3333-3341.

CARDIOVASC 2014; 13(1): 12-13