Intestinal metaplasia, a so-called Barrette epithelium, can develop from normal esophageal squamous epithelium due to various factors. This may develop into low-grade or high-grade dysplasia, which in turn may be associated with dangerous adenocarcinoma. The following article discusses the course, risk factors, and opportunities and necessities for surveillance. Therapy of “high-grade” dysplasias by mucosal resection or radiofrequency ablation shows very good results.

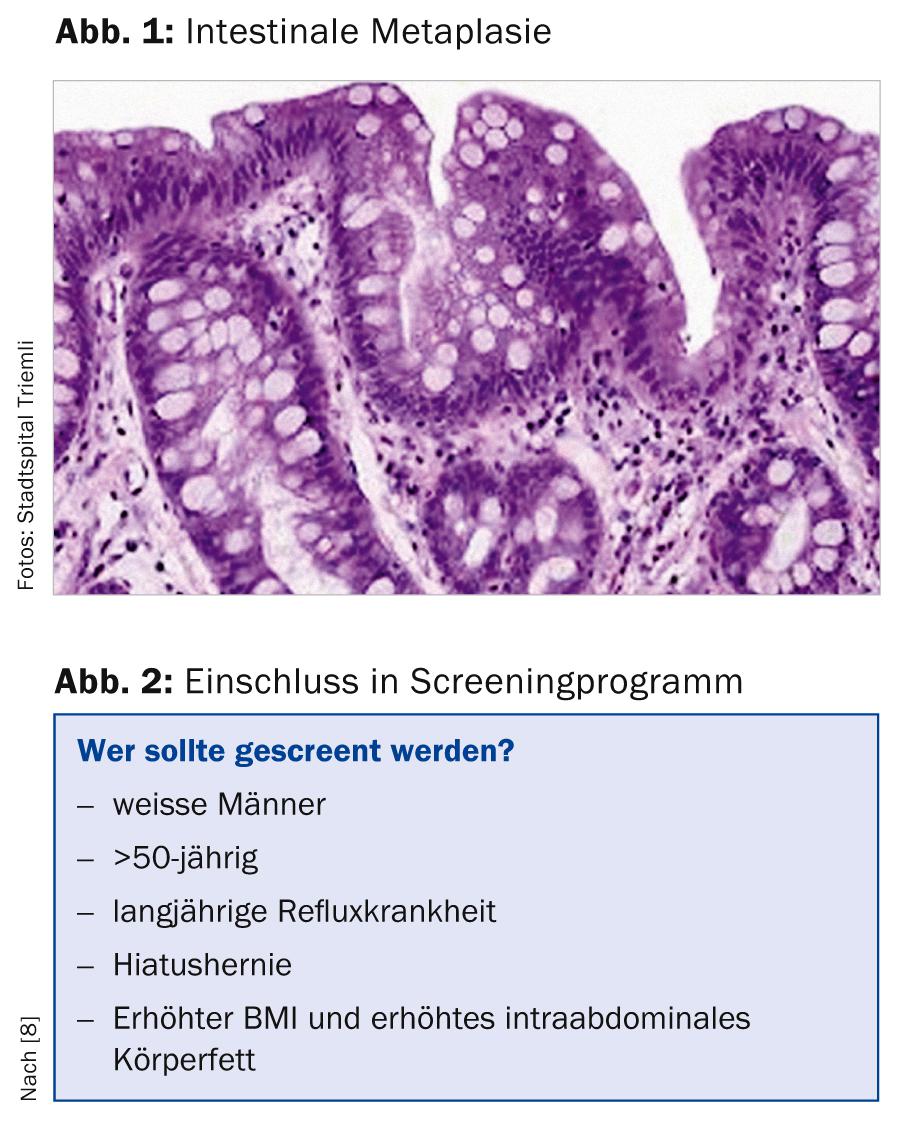

Barrett’s esophagus is defined (at least in our latitudes) as the presence of cylinder epithelium in the distal esophagus with additional specialized intestinal metaplasia (presence of goblet cells, Fig. 1). In other countries (e.g., England, France, or Japan), histologic evidence of cylinder epithelium alone is sufficient to diagnose Barrett’s esophagus [1, 2].

We distinguish long-segment Barrett’s esophagus (epithelial tongue at least 3 cm long) from short-segment Barrett’s esophagus (Barrett’s tongue shorter than 3 cm).

Course

Intestinal metaplasia can develop from normal esophageal squamous epithelium due to various factors and is found in approximately 5-20% of all upper panendoscopies. From this so-called Barrette epithelium, “low-grade” or “high-grade” dysplasias can develop, from which an adenocarcinoma can develop. Esophageal adenocarcinoma-especially when detected late-continues to have a very poor prognosis with a 5-year survival of just under 20% despite improved treatment options (neoadjuvant radiochemotherapy) [3, 4].

Known risk factors for the development of Barrett’s esophagus.

We know the following risk factors for the development of barrette epithelium [5, 6]:

- Age

- Male gender

- Reflux symptoms

- Caucasian descent

- Smoking

- Barrett’s esophagus length

- Central obesity

- Type 2 diabetes.

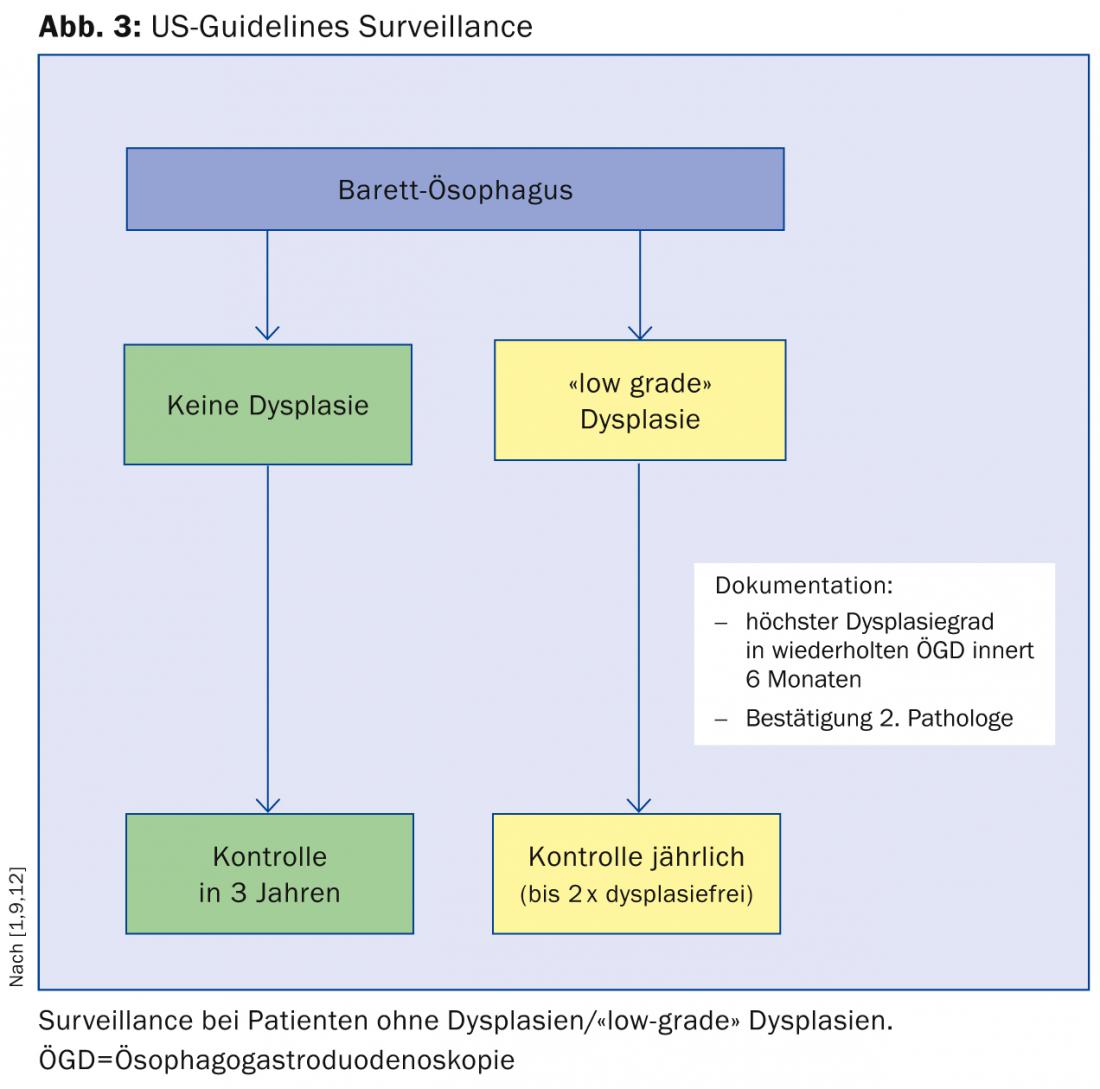

Screening and surveillance: general

The annual risk of esophageal adenocarcinoma was probably significantly overestimated in older studies and is at a low level of between 0.1 and 0.3% per year in patients with nondysplastic Barrett’s esophagus in more recent (and larger) studies. Patients with Barrett’s esophagus die in over 95% not from esophageal cancer but mainly from cardiovascular disease, pulmonary disease, or other tumor conditions, according to a cohort study from the United Kingdom [7]. For this reason, according to the American Gastroenterological Association (AGA), patients with multiple risk factors should be primarily screened (Fig. 2) [8]. The rationale for screening these patients is that Barrett’s esophagus is a precancerous condition that usually presents asymptomatically. In addition, as previously described, adenocarcinoma of the esophagus has a poor prognosis, which can be improved by early therapy.

The main argument against screening is that the natural progression from Barrett’s esophagus to carcinoma is small. In addition, endoscopies and biopsies carry certain (albeit small) risks and incur costs.

Surveillance, like screening, is about reducing mortality from esophageal adenocarcinoma. The inclusion in a surveillance program speaks for the fact that “high-grade” dysplasia or early carcinoma can be detected as early as possible and early interventions can lead to a reduction of follow-up costs and mortality. In addition, surveillance often gives both the patient and the physician a sense of security.

One argument against inclusion in a surveillance program is that endoscopic detection of dysplasia can be relatively difficult and randomized biopsy sampling can lead to “sampling errors.” In addition, histologic interpretation of the biopsies taken can also be difficult and, as mentioned previously, endoscopies carry potential risks and generate costs.

Screening and surveillance: guidelines

There are several international guidelines for the management of patients with Barrett’s esophagus. In the following, we would like to briefly discuss the guidelines of the American Society of Gastroenterology (ACG), to which we essentially adhere at Stadtspital Triemli (Fig. 3) [9]:

Patients with Barrett’s esophagus without dysplasia should undergo a second gastroscopy within one year and follow-up every three years if dysplasia remains undetected.

When “low-grade” dysplasia is detected, it is recommended that gastroscopy be repeated within six months and that dysplasia be confirmed by a second pathologist. Thereafter, annual checks are recommended until the mucosa is dysplasia-free twice.

When “high-grade” dysplasia is detected, confirmation by a second pathology institute is also required. The further procedure then depends on the age of the patient, the expertise of the respective center, and the comorbidities.

Therapies of Barrett’s esophagus and adenocarcinoma.

Proton pump inhibitor therapy: Therapy with a proton pump inhibitor (PPI, dosage 20-40 mg/d) as continuous therapy is recommended. This is despite the fact that there are no randomized placebo-controlled trials demonstrating that PPI therapy results in regression of metaplastic epithelium or a reduction in carcinoma development [8].

Therapies of “high-grade” dysplasias: Macroscopically visible, small-sized lesions are treated endoscopically by mucosal resection (mucosectomy) or radiofrequency ablation (RFA). Patients with large lesions should be discussed on an interdisciplinary basis between gastroenterologists and surgeons. However, according to the recommendations of an international multidisciplinary expert group, endoscopic resection is generally preferable to surgical therapy because it is associated with a higher complication rate [10].

During mucosectomy, larger mucosa areas are aspirated into a cap that is attached to the tip of the endoscope. Lesions can then be resected with a cutting unit. This method allows not only therapy of “high-grade” dysplasias and early carcinomas, but also definitive staging.

In radiofrequency ablation – the second widely used method for ablation of Barrett’s epithelium – Barrett’s mucosa is ablated through the use of radiofrequency energy released by a balloon.

The long-term result of these methods is very good.

For example, in a recent study, three years after radiofrequency ablation, 98% of patients remained dysplasia-free and 91% of patients were without evidence of Barrett’s mucosa [11].

CONCLUSION FOR PRACTICE

- The barrette epithelium may have “low-grade” or “high-grade” dysplasia and, at worst, dangerous adenocarcinoma.

- In patients with Barrett’s esophagus without dysplasia: a second gastroscopy (within one year) and follow-up (every three years) if dysplasia remains undetected.

- “low-grade” dysplasias: repeat gastroscopy within six months and confirmation by a second pathologist. Thereafter, annual checks until the mucosa is dysplasia-free twice.

- “high-grade” dysplasias: also a confirmation by a second pathological institute. The further procedure depends on the age of the patient, the expertise of the respective center and the comorbidities.

- Therapy with a PPI is recommended.

- Therapy of “high-grade” dysplasias by mucosal resection or radiofrequency ablation shows very good results.

- Sampliner RE, et al: Am J Gastroenterol 2002; 97: 1888-1895.

- Messmann H, et al: Z Gastroenterol 2005; 43: 184-190.

- Shaheen N, et al: Gastroenterology 2005; 128: 1554-1566.

- Siegel R, et al: Cancer statistics, 2012. Cancer J Clin 2012; 62: 10.

- Prasag G, et. al: Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol 2013; 11: 1108.

- Wani, et al: Clin Gastroent and hepatol 2011; 9: 220-227.

- Masoud S: Gastroenterology 2013: 144: 1375.

- AGA Institute Medical Position Panel: Gastroenterology 2011.

- Wang KK: AM J Gastroenterol 2008; 103: 788-797.

- Bennett, et al: Gastroenterology 2012; 143: 336.

- Shaheen NJ: Gastroenterol 2011; 141: 460-468.

- Sharma P: NEJM 2009; 361: 2548-2556.

HAUSARZT PRAXIS 2014; 9(1): 23-25