Insurance benefits must ultimately be decided by the legal practitioner in a binary fashion. Either such benefits are paid or they are denied. By comparison, medical thinking is less a matter of yes/no and more a matter of dimension. Difficulties between the two fields arise whenever the gap between scientific knowledge and legal concepts of disease is particularly wide. This article highlights this tension using three selected mental illnesses.

In this article, we highlight the tension between medicine and social security law using three selected mental illnesses.

Dependency disorders

From the medical point of view: The research results of the last 30 years with regard to the dependence syndrome of psychotropic substances have mainly shown that it is a chronic brain disease with detectable changes on the molecular, cellular, structural and functional level [1]. Basically, it is thus now considered a fundamental disorder of brain function with alterations in neurotransmitter metabolism, receptor availability, gene expression, and response to exogenous stimuli [1, 2]. Genetic-epidemiological studies have also shown that genetic factors have a significant influence on the long-term course of a dependence disease. In contrast, the influence of individual social environmental factors is most evident in the context of exposure to and initial use of psychotropic substances [3].

This neurobiological disorder is characterized, among other things, by a strong or compulsive craving for the substance, by the occurrence of withdrawal symptoms, by a development of tolerance (or dose increase), by the continuation of consumption despite negative social as well as health consequences, but also by its chronicity with frequent relapses after withdrawal treatments. Within addiction medicine, therefore, the viewpoint of drawing parallels to other chronic diseases such as diabetes mellitus or hypertension has become accepted today [4]. Accordingly, treatment approaches have also emerged that focus less on substance freedom (abstinence) and more on harm reduction [5–7]. To make matters worse, in more than half of cases there is another psychiatric comorbidity in addition to substance dependence, the treatment of which should be concurrent [8, 9]. Significant impairments in psychosocial functioning levels and, from a medical perspective, work ability are frequently observed and have been documented for decades [10–12].

From the point of view of social security law: dependency diseases, such as an alcohol dependency, do not in themselves constitute a disability within the meaning of the law (EVGE 1968 S. 278 Erw. 3 a). Also, according to case law, narcotic addiction alone cannot lead to disability. However, addiction may result in disabling health damage (e.g. cirrhosis of the liver, Korsakow’s syndrome) or may be a symptom of another disorder with disease value, e.g. schizophrenia or personality disorder (cf. BGE 99 V 28).

With regard to the legal evaluation of the so-called dual diagnoses (mental illness and addiction disease), the legal practitioner assumes that a medical distinction can be made between so-called induced mental disorders (caused by the addiction) and independent psychiatric disorders (associated with the addiction). It is also assumed that, as a rule, the psychological symptoms can be regarded as a consequence of the addiction (and thus not as a disease in their own right) and that these will improve of their own accord after withdrawal from the addictive substance.

Only if an independent mental illness exists can its effects contribute to the insured person’s disability (KSIH, para. 1013/1013.1). In the logic of the legal user, therefore, the insured person is often first required to undergo withdrawal treatment so that the person concerned can subsequently be assessed without the influence of addictive substances (Meyer T, 2004).

From a medical-scientific and also from a clinical point of view, an isolated consideration of the addictive disease and comorbid mental disorder is not tenable in many cases. With regard to the duty of cooperation required of the user of the law, it should also be borne in mind that substance withdrawal is a medical intervention that may well be accompanied by serious and, for example, in the case of alcohol, benzodiazepine and GHB withdrawal, lethal complications [13–16].

PTSD

From a medical perspective, the diagnosis of post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD), first listed in the DSM III, is a possible subsequent reaction to one or more traumatic events. A specific and known cause (trauma) is a necessary but not sufficient condition for the diagnosis [17]. About 10% of those who experience life-threatening trauma develop PTSD, depression, or both. Biological factors such as the genotype and neurobiological constitution of the affected interact with environmental factors (e.g., trauma severity, life experiences) to determine vulnerability or resilience in the aftermath of a traumatic event [18]. Twin studies have shown that more than 30% of the variance associated with the development of PTSD is due to a hereditary component [19]. Recent studies also suggest that interactions between polymorphisms of the FKBP5 gene (and the molecular chaperone Hsp90) and childhood environment predetermine the severity of later PTSD [19, 20]. Morphological changes in the brain have also been documented. Thus, it is now well established that trauma events (independent of an existing diagnosis) are associated with lower hippocampal volume [21].

Compared to DSM III (and ICD 10), which contained a narrow definition of trauma, DSM V expands the concept of trauma so that witnessing (as a witness, in mass media, etc.) is also recognized as a possible sufficient trauma situation [22].

The disorder is characterized by intrusive, distressing thoughts and memories of the trauma (intrusions), as well as images, nightmares, flashbacks, and partial amnesia. Furthermore, there are symptoms of overexcitement (sleep disturbances, jumpiness, increased irritability, concentration disorders, etc.), avoidance behavior and emotional numbness (general withdrawal, loss of interest, inner apathy) (cf. classifications according to DSM V and ICD 10).

Controversy surrounds the concept of “Late Onset Stress Symptomatology” (delayed-onset PTSD), particularly in the insurance medical context [23]. Delayed onset of PTSD symptomatology without initial symptoms is a rather rare phenomenon. More often, there is a delayed onset after initially present symptoms (reactivation) [24].

Consideration of mental comorbidity in diagnosis appears essential due to the high prevalence of comorbid disorders (including affective disorders, anxiety disorders, substance abuse, somatization disorders) and their clinical relevance [25, 26].

From the perspective of social security law: Although the PTSD criteria according to DSM are better operationalized and therefore have advantages over ICD 10 (Dreissig 2010), the highest court jurisprudence strictly follows the ICD 10 classification. Thus, in BGE 9C_228/2013 of 26. June 2013 that a less restrictive formulation of the trauma criterion (expansion of the trauma criterion in the sense of DSM IV and DSM V) and also a less restrictive formulation of the temporal latency (in the sense of delayed onset of the PTSD symptomatology) are therapeutically meaningful under certain circumstances and also described in the scientific literature, but must remain out of consideration when reviewing the eligibility for benefits of the disability insurance (see also BGE 9C_671/2012 of November 15, 2012).

Similar to somatoform disorders and some other clinical pictures, the ability to overcome PTSD and its effects is denied in the most recent supreme court rulings only exceptionally under narrow conditions. In this sense, the Federal Court assumes that PTSD does not necessarily have to be disabling. For the insurance medical assessment of the PTSD and its effects, therefore – in addition to the assessment of the concrete occupational and everyday functional limitations and existing resources – the medical and insurance medical evaluation of the possibly existing severe psychological and somatic comorbidity and previous treatment results, including the treatment of the PTSD, is also required. treatment motivation is required (cf. BGE 136 V 279 E. 3.2.1 p. 282).

Somatoform pain disorder

From the medical point of view: In clinical practice, there is a high lifetime prevalence (15-20%) of somatic symptoms without sufficient organic correlates, some of which can cause considerable suffering [27, 28]. Frequently, these symptoms are then classified as somatoform disorders after comprehensive clarification. They are now among the most common mental illnesses.

In practice, symptoms may relate to different organ systems (e.g., palpitations, dizziness, stomach pain, localized pain, paresthesias, etc.) or appear “generalized” (fatigue, generalized pain, feeling of weakness). Anxiety and depressive symptoms are also common [29].

A significant problem is often the exact diagnostic assignment, which is due to the heterogeneous nature of such disorders with regard to symptom type, duration, course and expression. The diagnostic categories are therefore highly controversial, which is why some authors argue for an adjustment of the diagnostic categories [28–32]. Such an adjustment has already been implemented in the new DSM V classification system [33].

Various neurobiological and psychodynamic explanations exist. Moreover, the current literature also emphasizes the proximity of anxiety, depression, and pain [34, 35]. Scientifically controversial is the classical view of psychosomatics, according to which “somatization” is caused by a diminished perception of emotions [36, 37].

Therapy for somatoform disorders is complex [38] and often characterized by significant losses in functional performance [28].

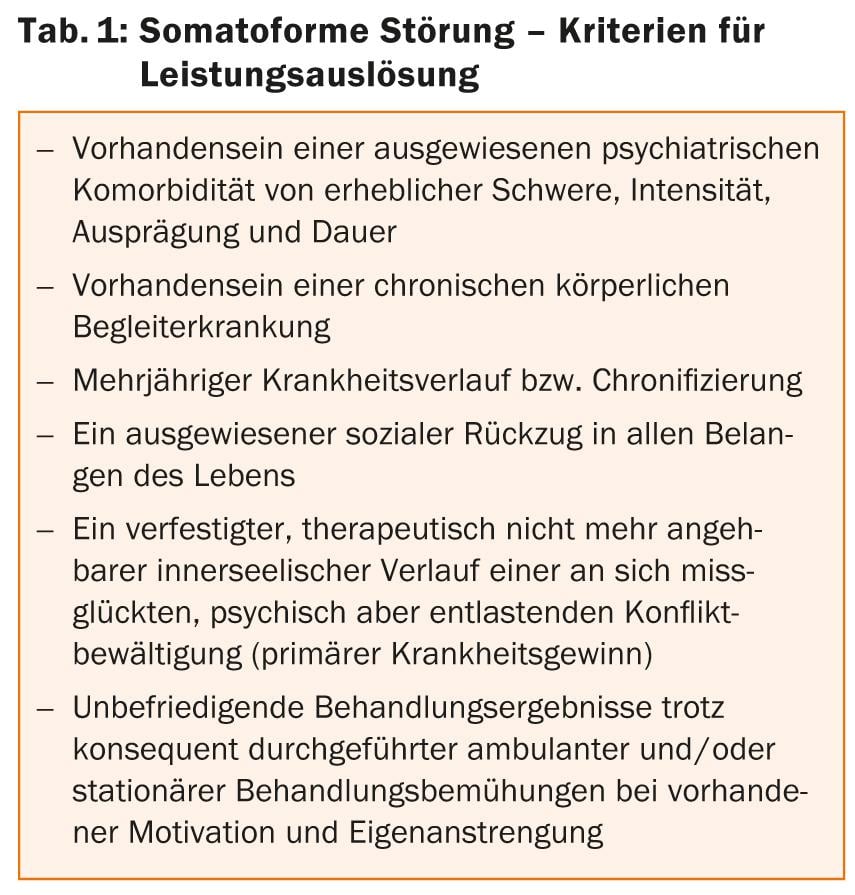

From the perspective of social insurance law: In view of the evidentiary difficulties that naturally arise with regard to pain, the subjective pain statements of the insured person are not sufficient on their own according to the standards of case law for the justification of (partial) disability (cf. BGE 130 V 352). Only in exceptional cases is a somatoform disorder considered by case law to be so severe that it could trigger benefits. In order to identify such exceptional cases, case law makes use of various auxiliary criteria following Foerster (cf. BGE I 224/06 of July 03, 2006). If these criteria are met (by a majority), the somatoform disorder becomes exceptionally performance-triggering (Table 1).

In particular, the assessment of the psychiatric comorbidity criterion is particularly challenging [1, 11-13]. This is because the existing anxiety and depression symptoms can occur in the context of the somatoform disorder and, from the point of view of case law, do not necessarily have to be regarded as an independent (significant) mental illness (cf. ICD 10 chapter F45). In recent years, mild to moderate depressive episodes have therefore generally been regarded by the courts as “concomitant symptoms” of the pain disorder (see BGE I 224/06 of July 3, 2006). In this context, it should be noted that the original Foerster criteria developed for prognostic course assessment have been made independent by case law into a legal-normative standard (oral communication lic. iur. A. Traub, presentation of September 13, 2013).

Discussion

The selected case studies of dependency disorder, PTSD, and somatoform pain disorder underline that there is a clear discrepancy between the current state of scientific research, especially on the etiology and functional effects of individual clinical pictures, and their evaluation by the courts. At the formal level, this is particularly evident in the adherence of case law to terminology that is not ICD-10-compliant from a medical point of view (primary and secondary addiction, päusbonog); at the substantive level, for example, in the use of moral-normative concepts rather than evidence-based ones (e.g., in the sense of ignoring psychosocial factors) and the demand for objectifiability and comparability of naturally subjective, intraindividual disease phenomena.

However, it must be stated that medicine is precisely unable to offer incontrovertible concepts and disease models on which jurisprudence, however, depends in order to make decisions that are predictable for the person subject to the law.

Thus, against the background of the application of different accepted scientific paradigms (e.g., psychodynamic vs. neurobiological explanatory models) by medical experts, divergent clinical and insurance medical assessments often occur in everyday life. From the medical side, therefore, the medical facts must be described as precisely and comprehensively as possible so that the legal concepts can then be applied on a clear factual basis.

This raises the question of the delineation of responsibilities between law and medicine. In this context, the task of the medical expert is not necessarily to bridge the gap between the medical research situation and case law described above, but to first make a very specific medical determination of the insured/patient’s limitation of benefits.

Following lic. iur. A. Traub (writer of the BG) the following procedure is recommended:

- The determination and description of the damage to health

- Impact assessment:

- Inventory of the basic functions that are limited due to the health damage.

Derived from this:

- In qualitative terms, a requirements profile for referral activities: What types of referrals are still possible?

And in this framework:

- the quantitative determination of the chargeable functional limitation: work (in)ability.

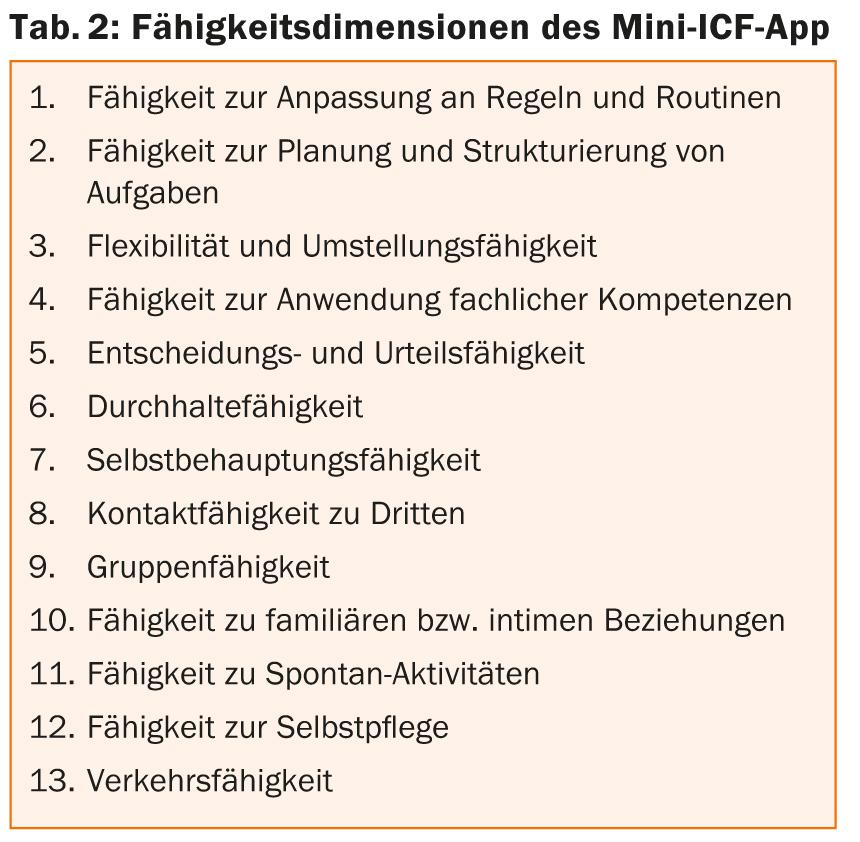

For implementation, the SGPP recommends in its current guideline for psychiatric assessments in the Federal Disability Insurance (2012) that the activity and participation disorders of the insured/patient be assessed following the mini-ICF app [39]. This is a third-party assessment tool to differentiate between disease symptoms and disease-related ability deficits [40]. The aim would be to derive the qualitative and quantitative work and performance capacity taking into account the resource situation of the insured/patient (Tab. 2). The results of the mini-ICF app should not be considered in absolute terms on the basis of the total score, but rather according to Linden et al. with the requirement profile of the insured person in the traditional occupational environment or in an activity adapted to the condition [40].

Both medical and legal issues play into the assessment of the “surmountability” of the complaints. In terms of delineation of responsibilities, the expert should comment on the medical basis for the legal decision [41]. The final assessment is then up to the legal practitioner.

Conclusion

Overall, the observed gap between current medical research and clinical experience on the one hand, and case law on the other, provides an explanation for why medical (or therapeutic) assessment of functional capacity (e.g., in somatoform pain disorders and dependency disorders) is in many cases incongruent with that of legal practitioners. In the authors’ view, knowledge of the different concepts in medicine and law would help to avoid misunderstandings on both sides.

Michael Liebrenz, MD

Acknowledgments: The authors would like to thank Br. Dr. med. A. Buadze (lecturer at the University of Zurich) and Hr. RA Frank Bremer, LL.M. (Lecturer at the University of St. Gallen HSG) for the critical review of the manuscript. Michael Liebrenz was supported by the Prof. Dr. Max Cloëtta Foundation, Zurich and the Uniscientia Foundation, Vaduz.

Literature:

- Leshner AI: Addiction is a brain disease, and it matters. Science 1997; 278 (5335): 45-47.

- Koob GF, Simon EJ: The Neurobiology of Addiction: Where We Have Been and Where We Are Going. J Drug Issues 2009; 39(1): 115-132.

- Merikangas KR, McClair VL: Epidemiology of substance use disorders. Hum Genet 2012; 131(6): 779-789. doi: 10.1007/s00439-012-1168-0.

- McLellan AT: Have we evaluated addiction treatment correctly? Implications from a chronic care perspective. Addiction 2002; 97(3): 249-252.

- Amato L, et al: An overview of systematic reviews of the effectiveness of opiate maintenance therapies: available evidence to inform clinical practice and research. Journal of substance abuse treatment 2005; 28 (4): 321-329.

- Marlatt GA: Harm reduction: Come as you are. Addictive behaviors 1996; 21(6): 779-788.

- Marlatt GA, Witkiewitz K: Harm reduction approaches to alcohol use: health promotion, prevention, and treatment. Addictive behaviors 2002; 27 (6): 867-886.

- Kessler RC: The epidemiology of dual diagnosis. Biological psychiatry 2004; 56 (10): 730-737.

- Minkoff K: Best practices: developing standards of care for individuals with co-occurring psychiatric and substance use disorders. Psychiatric services 2001; 52(5): 597-599.

- Uchtenhagen A: Health and social sequelae of substance abuse. Social and Preventive Medicine 1987; 32(3): 122-126.

- Uchtenhagen A: Long-term courses in adult toxicomaniacs. In: Long-term trajectories in addiction. Springer 1987: 137-148.

- McLellan AT, et al: Drug dependence, a chronic medical illness. JAMA: the journal of the American Medical Association 2000; 284(13): 1689-1695.

- Trevisan LA, et al: Complications of alcohol withdrawal: pathophysiological insights. Alcohol health and research world 1998; 22(1): 61.

- McDonough M, et al: Clinical features and management of gamma-hydroxybutyrate (GHB) withdrawal: a review. Drug and Alcohol Dependence 2004; 75(1): 3-9.

- Kanemoto K, Miyamoto T, Abe R: Ictal catatonia as a manifestation of de novo absence status epilepticus following benzodiazepine withdrawal. Seizure 1999; 8(6): 364-366.

- Ashton H: Benzodiazepine withdrawal: an unfinished story. Br Med J (Clin Res Ed) 1984; 288(6424): 1135-1140.

- Breslau N: The epidemiology of trauma, PTSD, and other posttrauma disorders. Trauma, Violence, & Abuse 2009; 10(3): 198-210.

- Jovanovic T, Ressler KJ: How the neurocircuitry and genetics of fear inhibition may inform our understanding of PTSD. The American journal of psychiatry 2010; 167(6): 648.

- Skelton K, et al: PTSD and gene variants: new pathways and new thinking. Neuropharmacology 2012; 62(2): 628-637.

- Hubler TR, Scammell JG: Intronic hormone response elements mediate regulation of FKBP5 by progestins and glucocorticoids. Cell stress & chaperones 2004; 9(3): 243.

- Karl A, et al: A meta-analysis of structural brain abnormalities in PTSD. Neuroscience & Biobehavioral Reviews 206; 30(7): 1004-1031.

- Friedman MJ, et al: Considering PTSD for DSM 5. Depression and anxiety 2005; 28(9): 750-769.

- Davison EH, et al: Late-Life Emergence of Early-Life Trauma The Phenomenon of Late-Onset Stress Symptomatology Among Aging Combat Veterans. Research on Aging 2006; 28(1): 84-114.

- Andrews B, et al: Delayed-onset posttraumatic stress disorder: a systematic review of the evidence. American Journal of Psychiatry 2007; 164(9): 1319-1326.

- Kessler RC, et al: Posttraumatic stress disorder in the National Comorbidity Survey. Archives of general psychiatry 1995; 52(12): 1048.

- Kessler RC, et al: Prevalence, severity, and comorbidity of 12-month DSM-IV disorders in the National Comorbidity Survey Replication. Archives of general psychiatry 2005; 62(6): 617.

- Jacobi F, et al: Prevalence, co-morbidity and correlates of mental disorders in the general population: results from the German Health Interview and Examination Survey (GHS). Psychological medicine 2004; 34(4): 597-612.

- De Waal MW, et al: Somatoform disorders in general practice: prevalence, functional impairment and comorbidity with anxiety and depressive disorders. Br J Psychiatry 2004; 184: 470-476.

- Mayou R, et al: Somatoform disorders: time for a new approach in DSM-V. The American journal of psychiatry 2005; 162(5): 847-855. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.162.5.847.

- Rief W, Sharpe M: Somatoform disorders-new approaches to classification, conceptualization, and treatment. Journal of psychosomatic research 2004; 56(4): 387-390. doi:10.1016/S0022-3999(03)00621-4.

- Sharpe M, Mayou R, Walker J: Bodily symptoms: new approaches to classification. Journal of psychosomatic research 2006; 60(4): 353-356. doi:10.1016/j.jpsychores.2006.01.020.

- Wessely S, Nimnuan C, Sharpe M: Functional somatic syndromes: one or many? Lancet 1999; 354(9182): 936-939. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(98)08320-2.

- American Psychiatric Association, DSM-5 Task Force: Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders: DSM-5. 5th edn. American Psychiatric Association, Washington DC 2013.

- Bennett RM: Emerging concepts in the neurobiology of chronic pain: evidence of abnormal sensory processing in fibromyalgia. In: Mayo Clinic Proceedings 1999. Elsevier, 385-398.

- Raison VMCL: Neurobiology of depression, fibromyalgia and neuropathic pain. Frontiers in Bioscience 2009; 14: 5291-5338.

- Henningsen P, et al: Somatization revisited: diagnosis and perceived causes of common mental disorders. The Journal of nervous and mental disease 2005; 193(2): 85-92.

- Hiller W, et al: Causal symptom attributions in somatoform disorder and chronic pain. Journal of psychosomatic research 2010; 68(1): 9-19.

- Kroenke K: Efficacy of treatment for somatoform disorders: a review of randomized controlled trials. Psychosomatic medicine 2007; 69(9): 881-888.

- Colomb E, et al: Quality guidelines for psychiatric assessments in federal disability insurance.

- Linden M, Baron S, Muschalla B: Mini-ICF rating for activity and participation disorders in mental illness: Mini-ICF-APP; a brief instrument for third-party assessment of activity and participation disorders in mental illness based on the World Health Organization’s International Classification of Functioning, Disability and Health (ICF). Huber 2009.

- Oliveri M, et al: Principles of medical assessment of reasonableness and work ability. Part 1. in: Swiss Medical Forum 2006; 420-431.

InFo Neurology & Psychiatry 2013; 11(6): 27-31.