Itching is the most commonly complained of skin organ symptom and is often felt worse than pain. Especially eczematous skin lesions are not infrequently additionally scratched bloody. In the case of generalized pruritus in the absence of evidence of primary inflammatory skin changes or evidence of an inflammatory dermatosis, it is important to think of internal diseases or malignancies as the cause. At the ISA in Munich, there were updates on chronic pruritus, atopic dermatitis, and chronic hand eczema.

Pruritus is an unpleasant sensory perception that is responded to with scratching [1, 2]. Often so extensive that acute and chronic itching become the main topic of pediatricians and dermatologists. Pruritus, for example, can be the predominant and most distressing symptom in atopics, with scratch marks dominating the picture, as Prof. Thomas Luger, MD, of Munster, ISA, said.

Chronic pruritus

Generalized or localized pruritus that persists for more than six weeks is defined as chronic pruritus and may have dermatologic as well as internal, neurologic, and psychiatric causes. Dermatoses with severe itching include urticaria, scabies, atopic dermatitis and psoriasis. They account for about 57% of the causes of chronic itching, as Dr. med. Stephan Braun from Düsseldorf explained. However, chronic pruritus may also be a symptom of an underlying internal systemic disease. Chronic pruritus most commonly affects patients with cholestatic liver disease, chronic renal failure, and hemato-oncologic disease. In 8% of cases, an exact cause cannot be clearly identified.

Due to the wide variety of causes that can lead to chronic pruritus, it has proven helpful to establish working diagnoses in order to plan the necessary diagnostics. The guidelines of the European Dermatological Forum (EDF) and the European Academy of Dermatology and Venereology (EADV) propose a classification into three working diagnoses:

- Pruritus on skin with inflammatory changes

- Pruritus with secondary scratch lesions and

- Pruritus without inflammatory skin changes [1].

If primary inflammatory skin lesions are present, an underlying inflammatory dermatosis is likely. If there is only pruritus without inflammatory skin changes, the diagnosis should be directed towards systemic causes. Lists of possible systemic causes and diagnostic suggestions can be found in the European and German guidelines on chronic pruritus [1, 2].

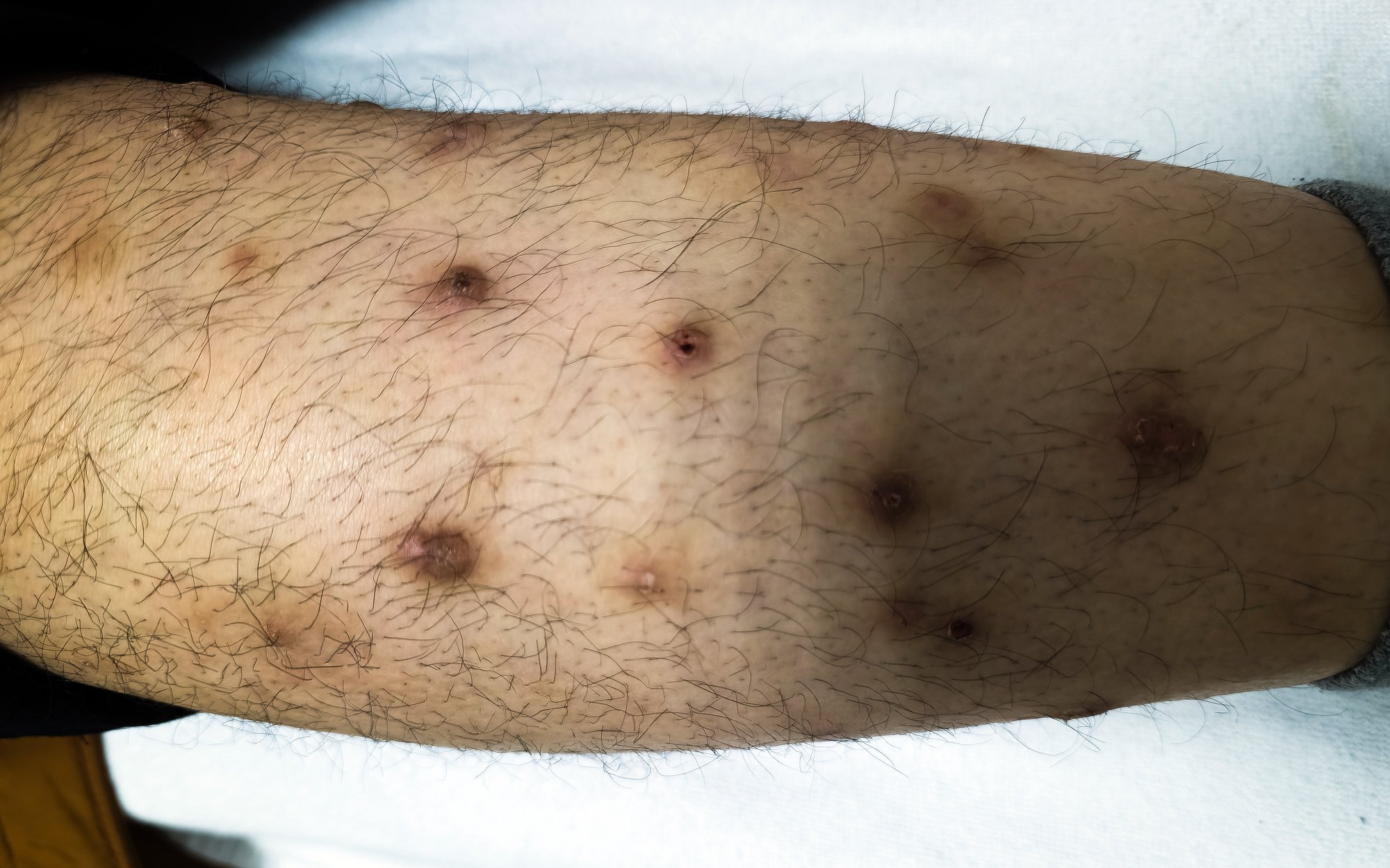

Secondary scratch lesions

Patients with secondary scratch lesions present a challenge. Chronic scratch lesions result from intense manipulation of the distressed patient’s skin and can be difficult to differentiate from classic inflammatory dermatoses, especially by nondermatologists. The so-called “butterfly sign” can help identify patients with secondary scratch lesions who do not primarily have inflammatory skin disease. This refers to the excision of inflammatory skin lesions in an area on the patient’s back that he cannot reach with his scratching fingers [2]. In the therapy section of the guidelines [1, 2], to which the expert further referred, numerous tables with further therapy options for chronic pruritus of various causes can be found in addition to general therapeutic measures (avoid trigger factors, intensive refatting of the skin to stabilize the skin barrier, anti-inflammatory and antiseptic measures for inflammatory/superinfected skin lesions). These include time-tested methods such as light therapy, capsaicin and the administration of immunosuppressants such as ciclosporin, Dr. Braun explained. However, in recent years, new antipruritic drugs have been identified thanks to advancing pruritus research [3]. For example, in a case series, the neurokinin1 receptor antagonist aprepitate showed a rapid significant antipruritic effect in patients with refractory chronic pruritus [4].

Other potential therapeutic options for the future include anti-interleukin-31 antibodies, histamine R4 antagonists, and autotaxin/lysophospholipid receptor inhibitors, which Dr. Braun concluded his presentation with.

Atopic dermatitis

Characteristics of atopic dermatitis (AD) include chronicity, eczema, and pruritus. 84% of patients with atopic dermatitis have sleep disturbances, and the average mean pruritus intensity on the visual analog scale (VAS) is 8 to 9, with peaks at night and in the morning. If a child suffers from AD, the quality of life of the entire family suffers. Prof. Thomas Luger, Muenster, MD, brought new insights into the prevalence and pathogenesis of AD to the ISA. For example, he pointed out that prevalence has increased over the past 30 years to as high as 25% in children and 3% in adults, a doubling. In addition, about 20% of pediatric cases are severe. The main diagnostic criteria include pruritus, chronic recurrent eczema, typical morphology and distribution of skin lesions, and a family history of the disease. The list of secondary criteria is long.

Prof. Luger explained that the distribution and characteristics of the lesions in relation to age groups are helpful in making the diagnosis. In children up to two years of age, erythematous papules and vesicles are found on the forehead, scalp, forearms; from approx. In adults, dry, scaly, erythematous papules and plaques predominate, usually on a few areas of the head, in the crook of the arm and/or back of the knee, on the palms of the hands with severe pruritus. Numerous special forms of AD are known, occurring at typical sites (scalp, eyelid, nipple, vulva, etc.) or with special manifestations (e.g., nummular type, prurigo type).

AD pathogenesis research has been able to identify both genetic factors (proteases, filaggrin) and the importance of the microbiome (each person harbors up to two kilograms of microbes!). “Central endogenous factors in the event seem to be the breakdown of the skin barrier and a shift in the colonization of the skin in AD,” Prof. Luger elaborated. Genetic defects affecting the skin barrier and certain shifts in the microbiome have already been associated with subtypes of AD [5, 6].

Since pronounced pruritus is one of the characteristic symptoms of AD and responds poorly to antihistamines, the investigation of neuroimmune interactions promises new, informative therapeutic approaches. However, Prof. Luger emphasized that it is of particular importance to prevent the vicious circle from starting up again once it has been broken by means of proactive therapy. Twice-weekly topical calcineurin inhibitors are an effective remedy here. In severe cases, the use of ciclosporin A is also an option once. The EDF guidelines already provide for this [7].

Chronic hand eczema

Chronic hand eczema (CHE) is a chronic and frustrating skin condition of the hands that occurs over a period of months and is associated with redness, scaling, skin thickening, blistering, edema, itching, and pain. Female gender, working with fluids, contact allergies, and AD are important risk factors.

CHE is a widespread problem, and the waiting time for an appointment at the specialist consultation with Sonja Molin, MD, at LMU in Munich is eight weeks. The one-year prevalence is high at 10%. Around 7% of those affected develop severe and chronic courses that can have far-reaching consequences. In a recent survey, 66.2% in the normal population said they would rather not take the hand of someone with the disease, and 45% felt repulsed [8]. However, it is not only patients who bear the burden of illness; the loss of work also affects colleagues. CHE may necessitate a change in occupation. Cost calculations show that severe cases with inpatient stay can incur up to 8400 euros per year in medical costs [9].

Alitretinoin (Toctino®), an anti-inflammatory and immunomodulatory vitamin A receptor agonist, has been available for severe CHE for several years and can produce amazing results in severe chronic hand eczema. Three approaches to action are postulated: Chemokine production, leukocyte activation and allergen presentation decrease measurably [10]. It is best to take the drug (caveat: contraception in women!) with the evening meal, Dr. Molin recommended, as patients then sleep through the most common side effect, an initial headache. Depending on tolerability, sometimes a dose reduction can help with other side effects. In the absence of a response to alitretinoin, it is also worthwhile to first question the diagnosis again.

Source: 3rd Munich International Summer Academy of Practical Dermatology (ISA), July 21-26, 2013.

Literature:

- Weisshaar E, et al: European guideline on chronic pruritus. Acta Derm Venereol 2012; 92(5): 563-581 at www.euroderm.org.

- Guideline of the German Dermatological Society “Chronic Pruritus” at www.awmf.org.

- Yosipovitch G, Bernhard JD: Clinical practice. Chronic pruritus. N Engl J Med 2013; 368(17): 1625-1634.

- Stand S: Targeting the neurokinin receptor 1 with aprepitant: a novel antipruritic strategy. PLoS One 2010; 5(6): e10968.

- Cork MJ: Epidermal barrier dysfunction in atopic dermatitis. J Invest Dermatol 2009; 129(8): 1892-1908.

- Kong HH, et al: Temporal shifts in the skin microbiome associated with disease flares and treatment in children with atopic dermatitis. Genome Res 2012; 22(5): 850-859.

- Ring J, et al: Guidelines of AD 1+2. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol 2012; 26(9): 1176-1193.

- Letulé V, et al: 2013 submitted

- Diepgen TL, et al: Cost-of-illness Analysis of Patients with Chronic Hand Eczema in Routine Care in Germany: Focus on the Impact of Occupational Disease. Acta Derm Venereol 2013 Mar 25.

- Homey B: Toctino (alitretinoin)- explaining the anti-inflammatory effect. JEADV 2010; 24: 1-20.