The course of an allergic reaction is not predictable. Our authors show what to look out for in anaphylaxis and why epinephrine should be used as the first drug.

Who doesn’t know this unannounced emergency? Shortly after a wasp sting, a patient is brought to the office with shortness of breath and general weakness. Eye-catching is a facial swelling, the “wheezing” is unmistakable, the face color changes from white to blue.

Rapid action is required here. Although anaphylaxis by definition reflects a severe life-threatening hypersensitivity reaction to an exogenous agent, in everyday practice milder general reactions such as urticaria or facial edema alone are also considered as such. Classically, the anaphylaxis term is limited to IgE-mediated immediate reactions, but clinically, immunologic mechanisms cannot be distinguished from nonimmunologic mechanisms [1].

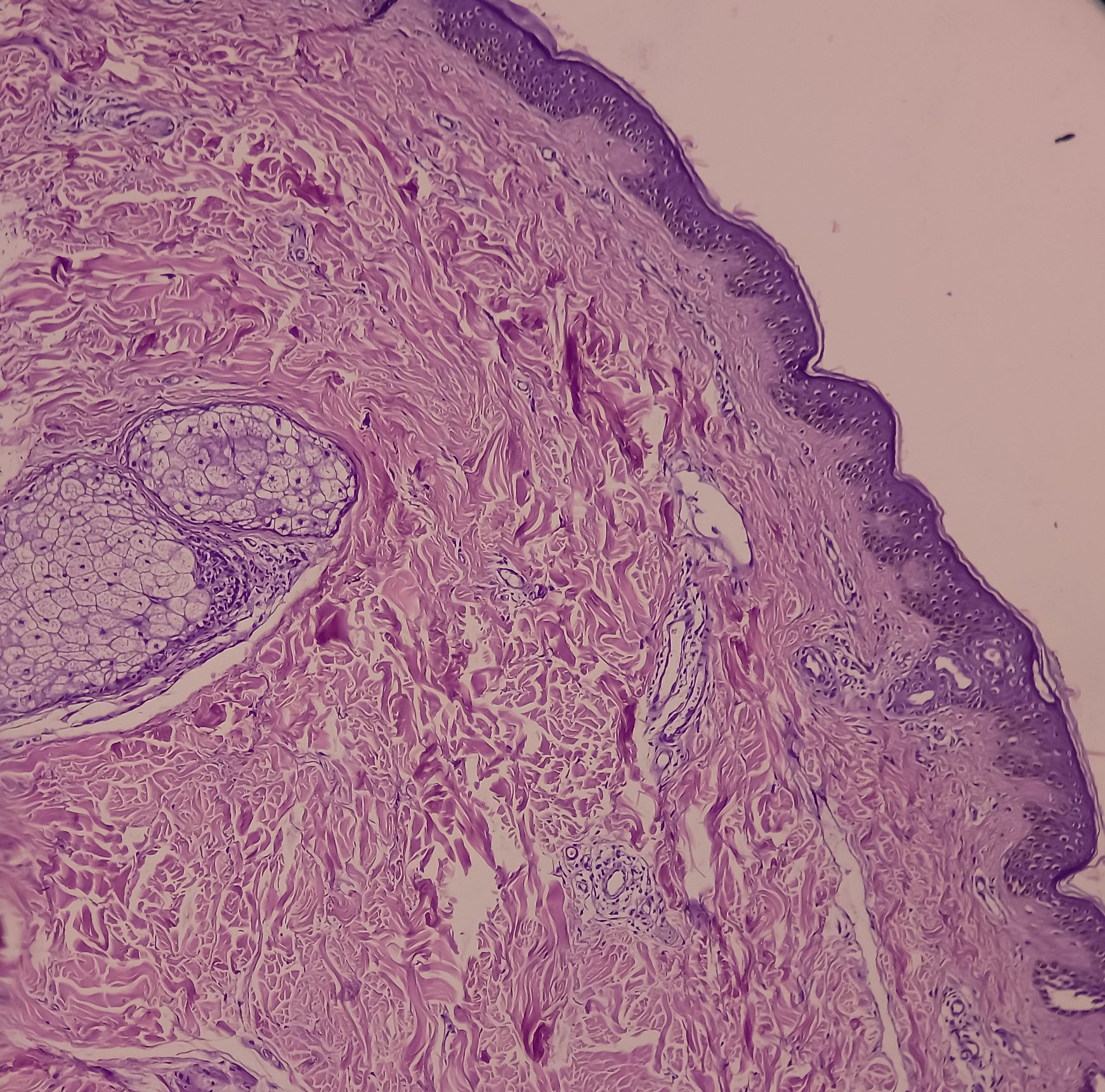

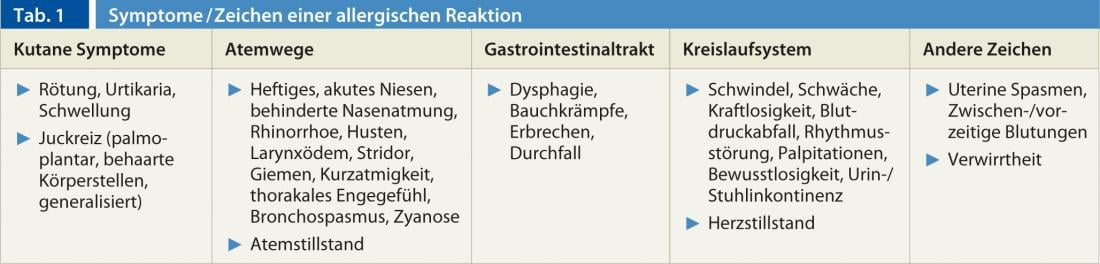

The diagnosis of anaphylaxis includes, in addition to the frequently manifest skin symptoms, symptoms of the respiratory and circulatory systems and, less frequently, of the gastrointestinal tract in direct connection with a suspected trigger (Table 1) . The most frequent causes of anaphylactic reactions are wasp and bee stings, medications (especially non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs and antibiotics) and food [1–3]. Anaphylaxis is based on degranulation of basophils and mast cells with consecutive release of histamine, leukotrienes, cytokines and other mediators [1, 2].

Symptoms and course

Usually anaphylaxis manifests itself a short time after a “contact”, e.g. after ingestion of a food or medication with a “funny” but unpleasant threatening feeling. Very often the affected person realizes a diffuse warmth in the body, a sudden violent itching in the palms of the hands and soles of the feet, or sometimes in the hairy regions of the body. The pruritus expands rapidly and is associated with exanthema or wheals. Respiratory symptoms (sneezing, blocked nasal breathing, asthma), nausea, nausea or a massive feeling of weakness can also develop rapidly (Tab. 1) . A few minutes may pass between the onset of the initial symptoms and the full-blown anaphylaxis, which may also end in death. Reactions often occur within 30 minutes, but anaphylactic shock can occur once after an hour [4]. The course of an allergic reaction is not predictable!

Therapy: The most important drug is adrenaline

Most patients who suffer anaphylaxis receive medical care with a delay of 30-60 minutes, so that the course of events may not infrequently impress as “stable” in the primary assessment. This may be an explanation why in many studies epinephrine has been used rather rarely in allergic emergency [4–7]. And this is quite contrary to the recommendation of the WAO and many national and international guidelines to use epinephrine as the first drug in anaphylaxis [8–11]. Every physician must be aware that antihistamines and corticosteroids are necessary to treat an allergic reaction, but that corticosteroids, even administered intravenously, are effective after one hour at the earliest [10, 11]. Even an antihistamine given orally shows a therapeutic effect after half an hour at the earliest. Although an antihistamine may be given first, followed by a corticosteroid, in cases of urticaria alone or mild facial swelling without respiratory or circulatory involvement. But in the presence or indication of dyspnea-whether or not bronchospasm is diagnosed-as well as circulatory involvement, epinephrine should be administered without delay.

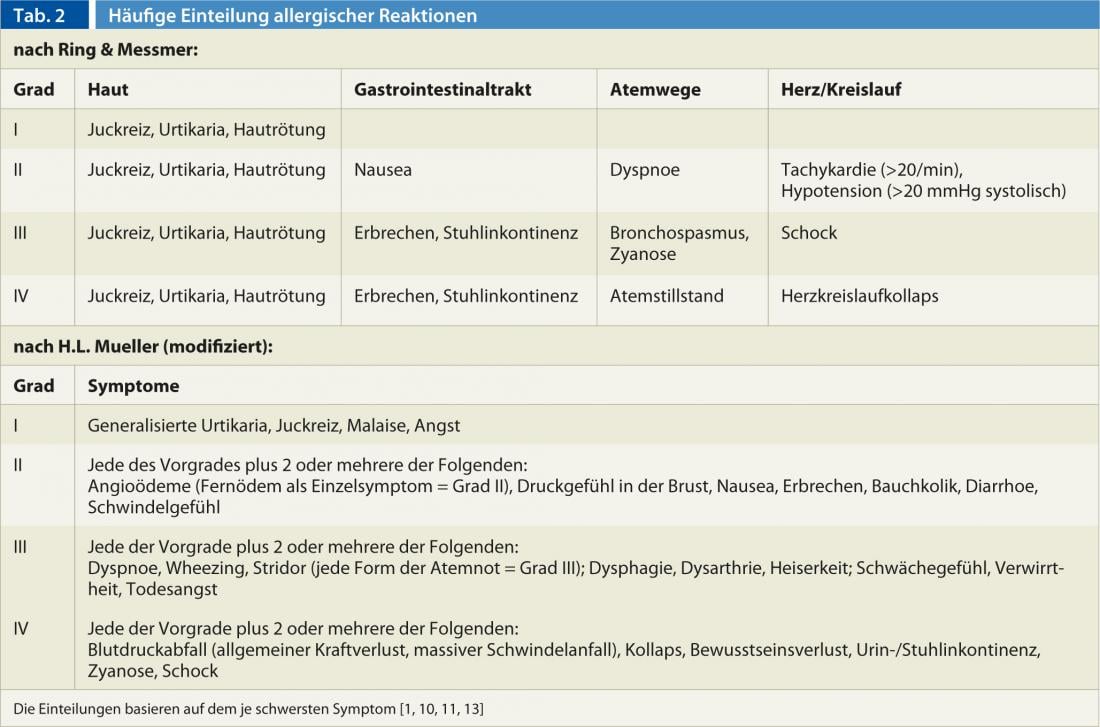

There is no absolute contraindication to using epinephrine in suspected anaphylaxis, regardless of initial symptoms [8, 10]. Since January 1, 2012, inhalable epinephrine preparations are no longer available worldwide, so that epinephrine is principally applied parenterally. Epinephrine should be administered intramuscularly rather than subcutaneously in emergencies because absorption takes less time intramuscularly and plasma levels rise more rapidly than with subcutaneous injection. The most ideal place to apply epinephrine i.m. is the anterolateral area of the thigh [11]. The dose in adults should be at least 0.3-0.5 mg (rule of thumb 0.1 ml per 10 kg body weight) (Table 2) [8, 10, 11]. If no therapeutic effect is apparent after three to five minutes, the administration of adrenaline should be repeated. The fear of many physicians that adrenaline triggers dangerous cardiovascular effects and that they therefore withhold adrenaline from a patient with an allergic reaction is generally unfounded. In fact, intravenous administration of epinephrine can be dangerous, so for intravenous administration, epinephrine should be diluted 1:9 with NaCl 0.9% and injected slowly in a controlled manner with ECG monitoring if possible. Adrenaline side effects such as chills, tremors, palpitations, anxiety, and dizziness are common but short-lived, but may cause uncertainty in the treating team. Severe or fatal side effects, mostly complex arrhythmias, have been reported sporadically, especially after i.v. and bolus administration of more than 2.5 mg epinephrine.

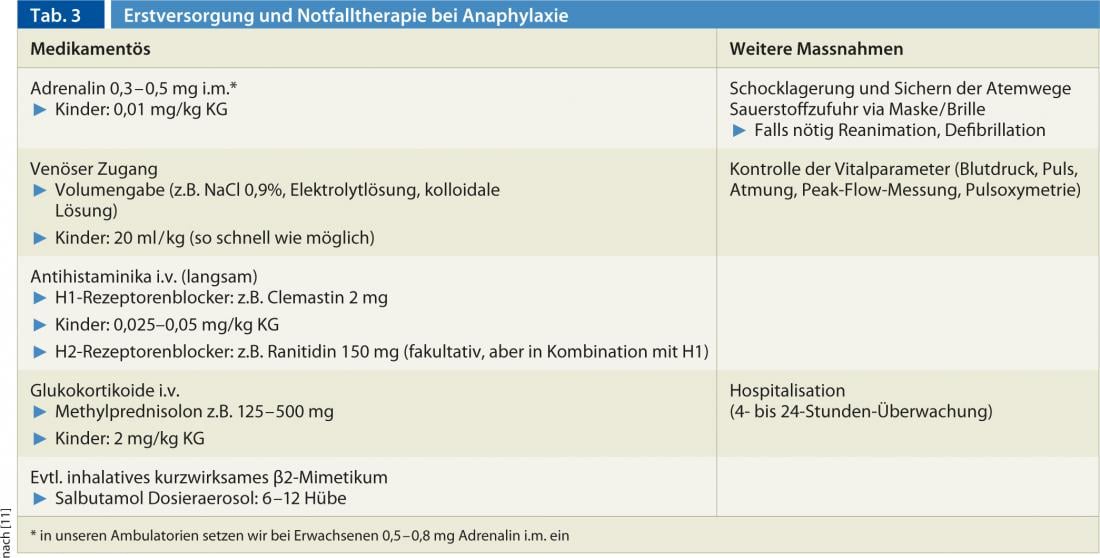

Additional therapeutic measures (Tab. 3)

Patients with low or unmeasurable blood pressure or shock should be positioned in a Trendelenburg position and, depending on the situation (if there is a risk of vomiting, loss of consciousness), in a lateral position [10, 11]. Since large volumes of fluid leave the central vascular compartment during a severe allergic reaction, venous access should be established as soon as possible to add volume. Volume loss to tissue can be as high as 35% within 10 minutes [12]. It does not matter whether crystalloids, HES (hydroxyethyl starch), or electrolyte solutions are used; HES has the advantage of staying intravascular longer than electrolyte solutions [10, 11].

An antihistamine should be administered after intramuscular epinephrine injection and after establishing venous access with ongoing infusion. The most common drug available intravenously is clemastine. It is important that clemastine be administered slowly intravenously, since a drop in blood pressure is virtually obligatory with rapid bolus administration. This is not an allergic effect, but a pharmacological one. Only then should corticosteroids be administered intravenously or later, when the patient has recovered, orally.

Corticosteroids, as mentioned above, are not first-line medications for a general allergic reaction. Corticosteroids have little effect on the immediate response i.e. mediators and cytokines released by mast and basophil activation, but they have an effect on the late responses (e.g. recruitment of eosinophils or lymphocytes). Corticosteroids, in combination with bronchodilators, are particularly effective in the treatment of bronchospasm or asthma. In acute therapy, 1-2 mg per kg body weight is sufficient.

H2 receptor blockers (e.g., ranitidine) should be administered only in combination with an antihistamine (H1 receptor blocker). The possibility that bradycardia or dyspnea may occur with the administration of H2 receptor blockers alone cannot be completely ruled out [10].

Inhalable epinephrine?

For asthmatic symptoms or bronchospasm, salbutamol can be administered nebulized or via an upstream chamber. It is important that the dose is chosen sufficiently high and that the inhalation is also repeated in case of non-success. In various emergency centers, epinephrine 1:1000 is used for inhalation in severe allergic reaction regardless of age and weight, with up to 5 ampoules of pure epinephrine administered for inhalation [11]. However, any inhalable epinephrine should only be used in the presence of a physician (→cardiac arrhythmias). Commercial inhalants containing epinephrine, which were available until recently, have not been available since January 1, 2012.

Procedure after acute therapy

Depending on the severity (Tab. 2) and course of the allergic reaction and response to treatment, the patient should be hospitalized and monitored after initial treatment. Comorbidities (e.g., COPD, cardiovascular disease) play a contributing role. Biphasic or protracted sequences are observed from time to time, especially in adults, but are less common in children [10, 11]. It is possible that some of these courses are the result of inadequate primary treatment. In patients on beta-blocker therapy – due to beta-receptor blockade with insufficient response to epinephrine – a protracted course with only slow recovery is to be expected. Although not every patient needs 24-hour monitoring, at a minimum, ensure that symptomatology is clearly regressed.

Dispensing and instructing emergency medications.

Every patient with a general reaction should be equipped with emergency medications regardless of severity and regardless of the triggering agent [10, 11]. The patient must be informed about the use of the emergency medication and instructed in the use of the epinephrine auto-injector when it is dispensed or even prescribed. In addition to the epinephrine auto-injector, the emergency kit is composed of an antihistamine (e.g., 2 tablets of cetirizine or levocetirizine) combined with a corticosteroid (e.g., prednisone 50 mg 2 tablets). In young children, antihistamines may be prescribed in drops (e.g., cetirizine 0.25 mg/kg bw) or as a syrup combined with water-soluble betnesol tablets.

Allergological clarification

More than 90% of anaphylaxis can be clarified by precise allergological clarification [11]. Various works have shown a not inconsiderable risk of recurrence of up to 40% in severe allergic adverse events, and especially in insect venom allergic patients the risk of recurrence is very often high [4, 7]. Therefore, every patient should be referred for an allergological evaluation after even a suspected general allergic reaction so that, in addition to identifying the cause, the affected person can also be instructed on essential behavioral measures (e.g., in the case of medication allergy, knowledge of alternative medications). In hymenoptera venom allergy, an excellent therapeutic effect can be achieved by means of specific immunotherapy [13]. The optimal time for an allergological workup has never been defined more precisely, but it is recommended that a workup be performed at the earliest three weeks after an acute and severe event, but if possible within six months. Depending on the cause, the patient is given an emergency ID card with necessary brief information.

CONCLUSION FOR PRACTICE

- Anaphylaxis is a rapid-onset, life-threatening general reaction and requires rapid therapeutic intervention.

- Regardless of whether the reaction is immunologic or nonimmunologic, epinephrine is the most important drug in suspected anaphylaxis and should be administered intramuscularly as soon as possible (adults 0.3-0.5 mg, children 0.01 mg per kg body weight).

- After an “allergic” general reaction, all patients should be equipped with emergency medication (including an epinephrine auto-injector and instruction in its use) and an emergency ID card, and should be referred for allergological evaluation within six months if possible.

Prof. Arthur Helbling, MD

Michael Fricker, MD

Literature:

- Scherer K, Helbling A, Bircher AJ: Curriculum: Anaphylaxis – Clinic, Triggers and Aggravating Factors. Switzerland Med Forum 2011; 11(25): 403-433.

- Lieberman P, Camargo Jr. CA, Bohlke K, Jick H, Miller RL, Sheikh A, Simons FER: Epidemiology of anaphylaxis: findings of the American College of Allergy, Asthma and Immunology Epidemiology of Anaphylaxis Working Group. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol 2006; 97: 596-602.

- Hompes S, Kirschbaum J, Scherer K, Treudler R, Przybilla B, Henzgen M, Worm M: First data of the pilot phase of the anaphylaxis registry in the German-speaking area. Allergo J 2008; 17: 550-555.

- Rohrer C, Pichler WJ, Helbling A: Anaphylaxis: clinic, etiology, and course in 118 patients. Schweiz Med Wschr 1998; 128: 53-63.

- Clark S, Bock SA, Gaeta TJ, Brenner BE, Cydulka RK, Camargo CA: Multicenter study of emergency department visits for food allergies. J Allergy Clin Immunol 2004; 113: 347-352.

- Clark S, Long AA, Gaeta TJ, Camargo CA: Multicenter study of emergency department visits for insect sting allergies. J Allergy Clin Immunol 2005; 116: 643-649.

- Helbling A, Müller U, Hausmann O: Anaphylaxis – Reality in acute therapy and preventive measures. Analysis of 54 patients from a specialized city hospital. Allergology 2009; 32: 358-364.

- Kemp SF, Lockey RD, Simons FER, et al: Epinephrine: the drug of choice for anaphylaxis. A statement of the World Allergy Organization. Allergy 2008; 63: 1061-1070.

- Alrasbi M, Sheikh A: Comparison of international guidelines forthe emergency medical management of anaphylaxis. Allergy 2007; 62: 838-841.

- Ring J, Brockow K, Duda D, Eschenhagen T, Fuchs T, Huttegger I, et al: Acute therapy of anaphylactic reactions. Guideline of the German Society of Allergology and Clinical Immunology (DGAKI), the Medical Association of German Allergists (ÄDA), the Society for Pediatric Allergology and Environmental Medicine (GPA), and the German Academy of Allergology and Environmental Medicine (DAAU). Allergo J 2007; 16: 420-434.

- Helbling A, Fricker M, Eigenmann P, Bircher A, Müllner G, Köhli-Wiesner A, Schmid-Grendelmeier P, Spertini F, Pichler W: Emergency treatment in allergic shock. Switzerland Med Forum 2011; 11(12): 206-212.

- Fisher MM: Clinical observations on the pathophysiology and treatment of anaphylactic cardiovascular collapse. Anaest Intensive Care 1986; 14: 17-21.

- Hausmann O, Jandus P, Haeberli G, Müller UR, Helbling A: Insect venom allergy-most important triggers are wasp and bee stings. Overview of the clinic, diagnosis, therapy and prognosis. Switzerland Med Forum 2010; 10(41): 698-704.