If back pain becomes chronic, this results not only in direct costs (consultations, diagnostics, therapy) but also in high indirect costs (lost working hours, strain on the social system). According to current scientific knowledge, a multimodal approach based on the bio-psycho-social model is superior to a unidimensional treatment concept for chronic pain.

The term “non-specific back pain” describes a basically benign condition. In contrast to specific pain, where there is a diagnosable cause for the pain (e.g. tumor, infection, fracture, herniated disc, etc.), no clear evidence of a specific cause can be elicited for nonspecific pain. Nonspecific back pain should therefore not be considered as a local disturbance of one or more movement segments, but as a complex pain and discomfort syndrome [1].

Usually, back pain is self-limiting. The recovery rate of acute back pain is 90%. In about 5% of cases, there is a slightly longer course, and 2-7% of patients develop chronic pain [2].

In the context of back pain, the term “chronic” describes much more than the mere duration of the complaints. Rather, chronic back pain develops slowly and progressively in most cases, without a triggering cause being identifiable. In the course of time, the chronification leads to an independent clinical picture, which is characterized by psychological stress, depressive symptoms and a lack of processing mechanisms [3].

Epidemiology and socio-economic consequences

The epidemiology of back pain has been well studied in many international and national studies. Point prevalence ranges from 12 to 33%, and one-year prevalence ranges from 22 to 65% [4]. In addition to gender (women are more commonly affected than men), the level of education is an important risk factor for the occurrence of back pain [5].

Back pain causes considerable costs, it is one of the most expensive diseases in industrialized countries. The total cost incurred by chronic low back pain is reported to be 0.7-1.7% of gross domestic product [6, 7]. Of the costs incurred, 15% are direct costs to the health care system, and 85% of the costs are due to lost productivity due to work disability [8].

Management of chronic nonspecific back pain.

The optimal treatment of chronic nonspecific back pain consists of a thorough diagnosis as well as multimodal therapy. The goal of treatment, in addition to excluding specific diseases to be treated, is to promote understanding of the disease and prevent harmful disease behavior. In the best case, the prompt initiation of somatic, psychotherapeutic and movement therapy measures can maintain or restore the ability to work and prevent or reduce disability.

Diagnostics

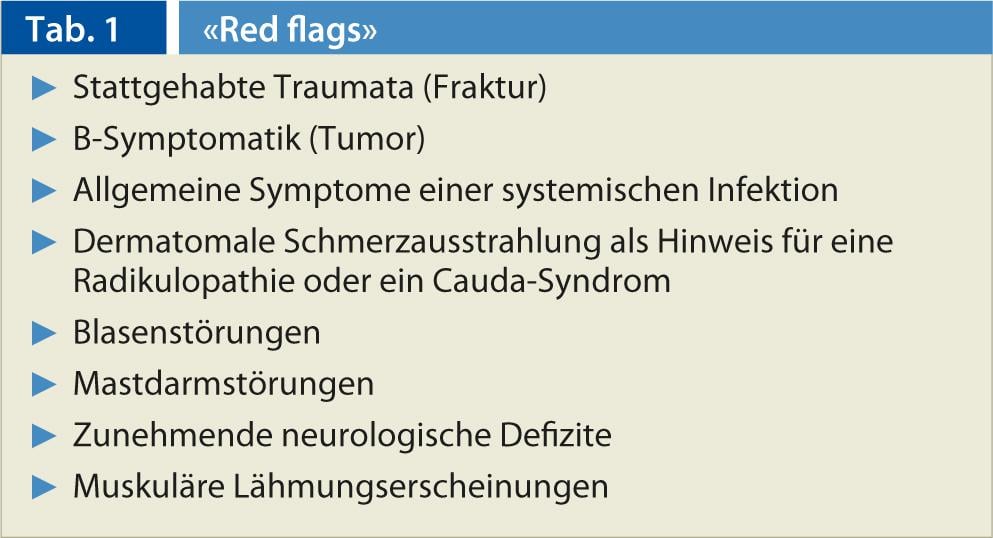

A detailed medical history and a comprehensive clinical examination are the cornerstones of diagnostics. The medical history should include information on the pain characteristics, such as localization and radiation of the pain, onset of the complaints, triggering, exacerbating or alleviating factors, the diurnal course, degree of impairment in the performance of everyday activities, and already indications of psychosocial risk factors. It is important to find warning signs for a treatable specific disease, so-called “red flags” (Tab. 1).

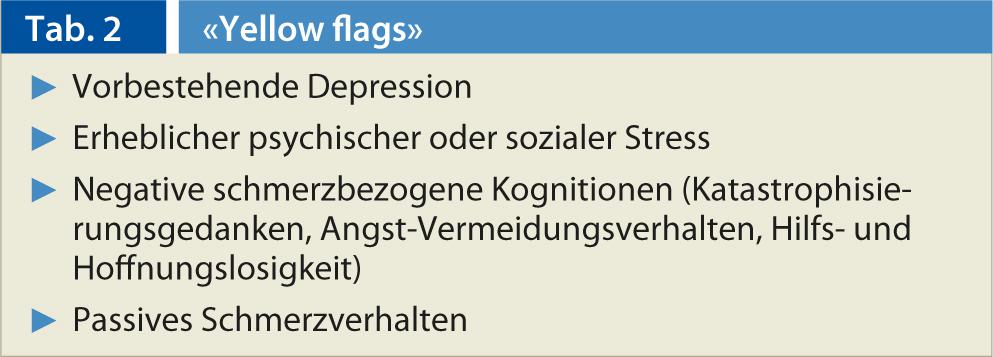

Diagnostics also serves to objectify the complaints and the resulting functional disorders as a basis for monitoring the course of the disease. The use of standardized questionnaires and/or documentation forms can be useful for this purpose. The third goal of diagnostics is to identify factors that pose a risk of chronicity of pain, the so-called “yellow flags” (Tab. 2).

If the careful history and clinical examination reveal no evidence of dangerous courses and other serious pathologies, no further diagnostic measures are initially necessary.

Therapy

The therapy of chronic non-specific back pain is based on the one hand on the pain and on the other hand on the functional limitation of the patient. The focus is on activating those affected. In particular, attention should be paid to the presence of risk factors for the chronification of acute low back pain (“yellow flags”). Multimodal and interdisciplinary treatment should be started as early as possible, as monomodal treatment concepts are only indicated for acute and subacute pain [9, 10].

At the somatic level, the best evidence exists for exercise therapy of any form. No specific type of exercise was found to have an advantage over any other type (aerobic exercise, muscle training, stretching exercises, etc.). For this reason, the type of exercise should depend on the patient’s preferences [11, 12]. Supportive to exercise therapy, manipulation/mobilization can be beneficial in individual cases [13]. Non-drug procedures such as prescription of bed rest, massage, interference therapy, laser therapy, magnetic therapy, or occupational therapy cannot be recommended. Notably, no invasive procedure, either percutaneous or surgical, has been able to show improvement in nonspecific back pain.

To support the treatment, it may be useful to use acupuncture as well as TENS therapy as additional non-drug methods.

The indication for drug therapy in chronic non-specific back pain is temporary use in the phase in which activating therapy measures are implemented. Here, analgesics (both non-opioids and opioids as well as muscle relaxants) should be taken according to a fixed schedule, and the need for therapy should be checked by interrupting administration after only a few days. Opioids should be considered only when patients fail to respond to non-opioids. In the case of muscle relaxants (especially benzodiazepines), particular attention should be paid to the considerable potential for dependence; chronic use of a benzodiazepine can also significantly complicate active multimodal therapy.

Similarly, antidepressants (especially tricyclic antidepressants) are used for pain management. However, the preparations of this substance class have been shown to be no more effective than placebo in terms of pain relief, improvement of functional impairment and depression [14].

At the psycho-social level, there is clear evidence that cognitive behavioral therapy, especially when combined with relaxation techniques, can achieve a reduction in pain intensity [10, 15]. No differences in effectiveness are found between the different types of behavioral therapy (based, for example, on the cognitive-behavioral, the respondent, or the operant model).

CONCLUSION FOR PRACTICE

In summary, the best evidence for the treatment of chronic nonspecific low back pain exists for multimodal therapy programs [16]. Here, on the one hand movement therapy and on the other hand behavioral therapy are carried out and combined with relaxation techniques (e.g. progressive muscle relaxation according to Jakobson) and patient education.

Literature list at the publisher

Tim Reck, MD