Around 80% of ADHD persists into adulthood. However, only a small proportion of affected adults are diagnosed, as the symptoms change and comorbidities are often in the foreground. An effective treatment model is multimodal and includes psychoeducation, psychotherapy and pharmacotherapy.

A hyperactive child? It will grow! What used to be conventional wisdom has proven to be incorrect over time. It is now known that although attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) manifests itself in childhood, it remains symptomatic in the majority of those affected in adulthood due to a high tendency to become chronic, and some also require clinical treatment. In children and adolescents, the prevalence is between 3% and 5%, in adults it is assumed to be 1-4%. Accordingly, the persistence of the developmental disorder is around 80% [1–4].

No disturbance of modern times

Everyone associates ADHD with the story of the fidget spinner. The first behavioral abnormalities in childhood that correspond to ADHD or hyperkinetic disorder can be traced back to the middle of the 19th century. In a historical overview of ADHD in this context, reference is made to the work of Hoffmann, Maudsley, Bourneville, Clouston and Ireland, among others [5]. Kramer and Pollnow (1932) and Chess (1960), for example, went on to provide conceptually advanced specialist medical descriptions of hyperkinetic disorders in childhood [6,7]. The fact that the disorder can continue to manifest itself in adulthood is largely due to Paul Wender’s working group in the USA in the mid-1970s. It conducted the first systematic studies with adult ADHD patients, the results of which played a key role in shaping the new approach [8,9].

Disease often masked

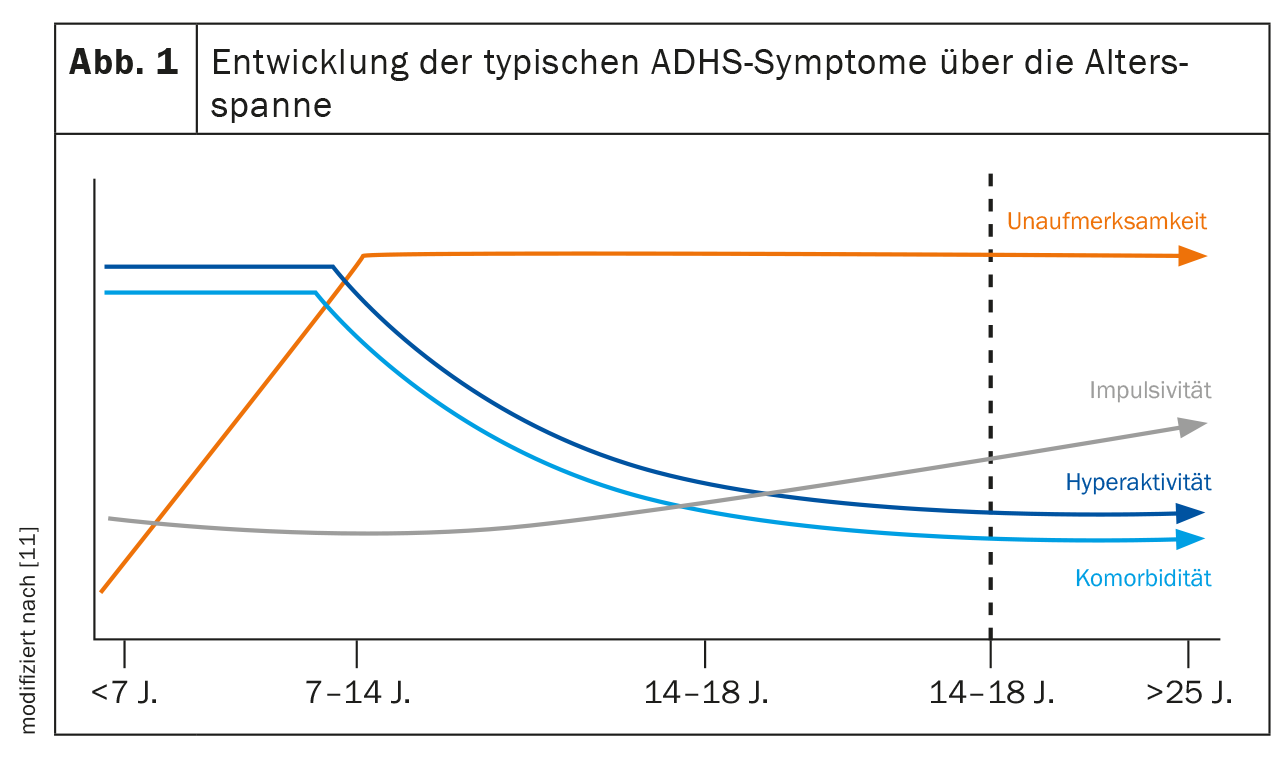

However, adult ADHD is often not recognized. Experts estimate that significantly fewer than 20% of patients are officially diagnosed [10]. This is due to two main factors. On the one hand, there is an age-dependent change in the main symptom triad of attention deficit disorder, hyperactivity and impulsivity (Fig. 1) [11]:

- While motor hyperactivity is the main focus of attention in childhood, this picture often shifts to inner restlessness as the child grows up.

- Attention deficit persists. It persists in 80% of those affected. Difficulties in this area then become apparent, for example, in the organization of work.

- Impulsivity decreases in 40% of patients, but is often still expressed in inappropriate comments or when participating in road traffic.

- Disorganization and emotional dysregulation often increase in severity as additional symptoms in early adulthood.

Thus, hyperactivity that is clinically conspicuous in childhood is usually more inconspicuous or modified in adults, for example, as nervous foot bobbing or finger drumming during periods of forced inactivity. Many sufferers experience situations such as long-haul flights and visits to the cinema/theater with a high level of inner tension due to their restricted mobility and therefore try to avoid them in everyday life. According to clinical observations, a strong urge to exercise is not infrequently lived out in extreme endurance sports or high-risk sports.

Increased risk of accidents in untreated patients

This fact is given significance by the fact that adult ADHD is associated with a 143% increased risk of accidents [12]. The probability of a car accident alone is three times higher [13]. Estimates lead to the conclusion that around 22% of all car accidents could have been prevented if those affected had received adequate treatment, including pharmacological treatment [14]. In addition to attention deficit and distractibility, accident-causing risk factors include slower reaction time and overestimation of driving skills due to impaired self-awareness [15]. One study examined the prevalence of adult ADHD in a population of accident victims at two trauma hospitals [16]. The results show that among accident victims, affected individuals with AHDS were significantly overrepresented. However, only 17% of those affected were already aware of the disease. Of these, only a third were treated pharmacologically.

When the attention is missing

Impairments of attention and concentration caused by disorders often become apparent when affected adults describe problems in their (professional) everyday life. Due to a high level of distractibility and openness to stimuli, there may be difficulties with the organization of processes and with the planning and structuring of the work to be done. Accordingly, the overall work behavior is not infrequently characterized by inefficiency and poor time management. Problems with concentration can provoke errors in the workplace and generally impair work performance. The lack of impulse control can also cause problems for those affected at work – but also in their relationship, family and social environment. Typical behavior here is unasked-for intrusion into conversations and a tendency to take unthought-out, spontaneous actions [17].

Comorbidities often dominate

The second reason why adult ADHD is often overlooked is the possible presence of comorbidities. ADHD rarely occurs as an isolated disorder in adult psychiatric practice. In about four out of five affected persons, the clinical picture is completely or partially overlaid by at least one other mental illness [18]. A multicenter observational study of adults showed that comorbidities are the rule rather than the exception in adult ADHD patients: At the time of ADHD diagnosis, psychiatric morbidity was found to be 66.2%, with more men affected [19]. The most common comorbidities of ADHD in adults include (Fig. 2) [18]:

- Addictive disorders

- Anxiety disorders

- Affective disorders such as depression, mania or bipolarity.

The exact etiologic relationship between ADHD and these comorbidities is unknown. However, ADHD as a pediatric disorder is usually thought to manifest temporally before the comorbid disorder. Psychological comorbidity could then develop secondarily, for example as a result of long-term negative experiences and frustrations co-induced by ADHD. Energy-consuming adaptation efforts could also play a role. In order to cover up deficits, those affected resort to compensation mechanisms which, however, cost a lot of energy in the long run. This is because the brains of people with ADHD filter information less automatically than those of healthy people. The excess of information can then lead to uncertainty and compensatory perfection. Accordingly, patients with ADHD are more often in stressful situations, which can trigger stress. The combination of increased vulnerability – as is the case with ADHD – and increased stress can then lead to a depressive illness. It is clinically relevant that these secondary disorders develop a dynamic over the course of the disease and can dominate the overall clinical picture and mask the AHDS [20]. The estimated prevalence of depression in adults with ADHD is more than nine times higher than in the healthy cohort [21]. In addition, ADHD symptoms are associated with more episodes, suicidality and a higher severity of depression [22].

Few patients with depression, bipolar disorder, or anxiety disorder also receive a concurrent ADHD diagnosis. One reason for this is that many symptoms overlap. The core symptom of depression, for example, is emotional disturbance, including sadness, self-esteem problems and sleep disorders. The progression can range from a depressive episode with complete remission of symptoms to recurring episodes to a long-lasting depressive mood. Dysthymia is often found in patients with ADHD and comorbid depression. A negative self-image, disturbed sleep or emotional dysregulation can be observed in both disorders. In most cases, patients are then treated for depression, and coexisting ADHD is often overlooked. This may have a negative impact on the therapeutic success of the aforementioned comorbidities. If the treatment of the depression does not respond, a more detailed examination should therefore be carried out in the direction of ADHD. This is because successful treatment of the underlying disease can also help to improve the comorbidities by improving the core symptoms [23–25]. Without a diagnosis, those affected are denied access to evidence-based treatment.

Multimodal treatment model

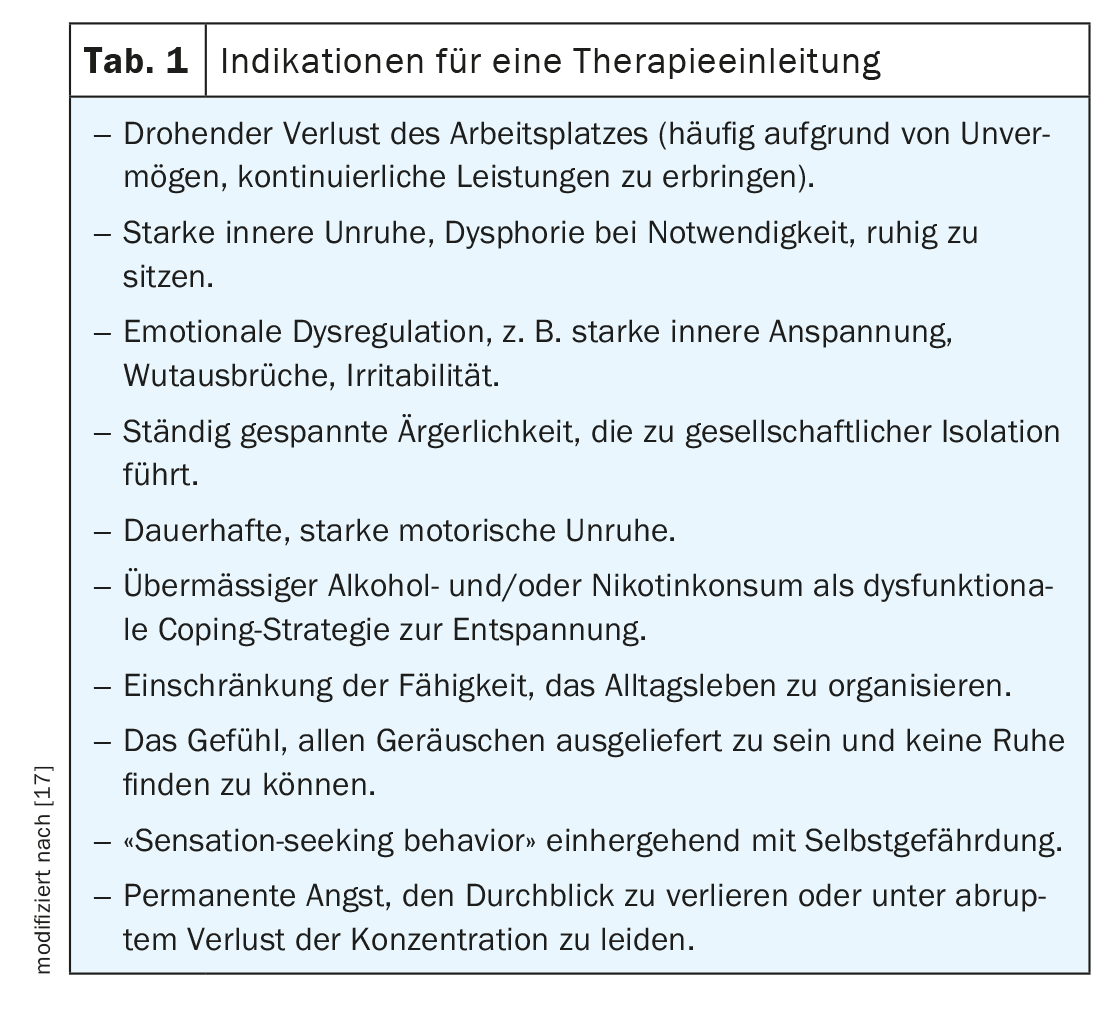

Treatment should take into account both the core ADHD symptoms and the presence of comorbid disorders and should therefore generally be multimodal. This includes the use of the available therapy modules of psychoeducation, psychotherapy and pharmacotherapy (Table 1). As part of the therapy concept, non-drug measures such as education and psychoeducation are suggested as a basis at the start of therapy. In addition, psychotherapeutic interventions are recommended, especially for the self-esteem problems often present in affected individuals or other concomitant diseases [26]. Drug treatment may be necessary in order to create a neurobiological basis that allows patients access to further therapeutic measures such as behavioral therapy. The goal of all therapeutic interventions is to achieve the most comprehensive symptom remission and restoration of psychosocial functioning.

Evidence-based pharmacotherapy

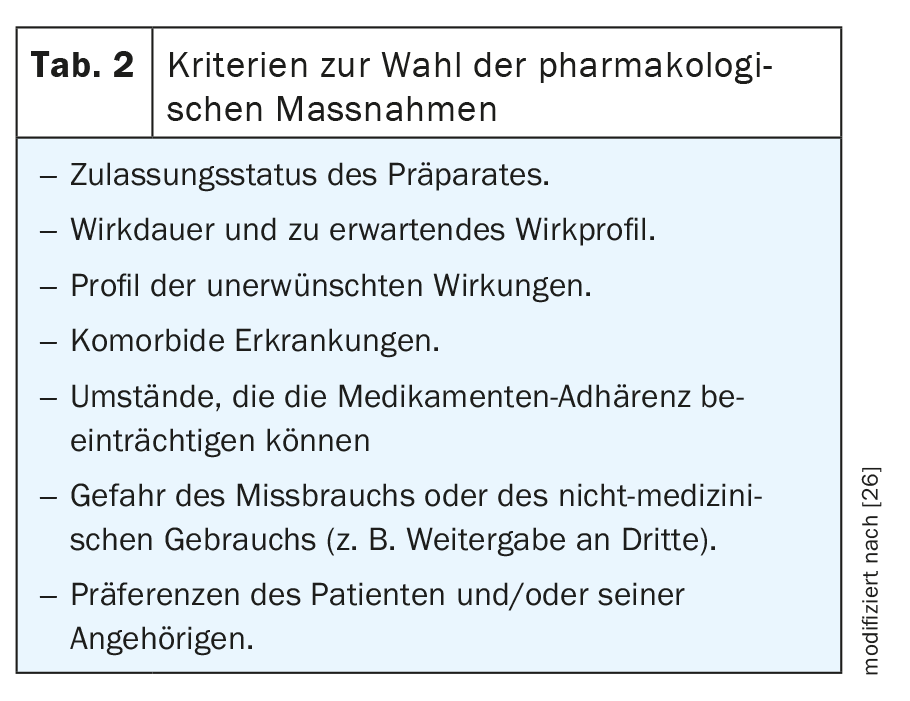

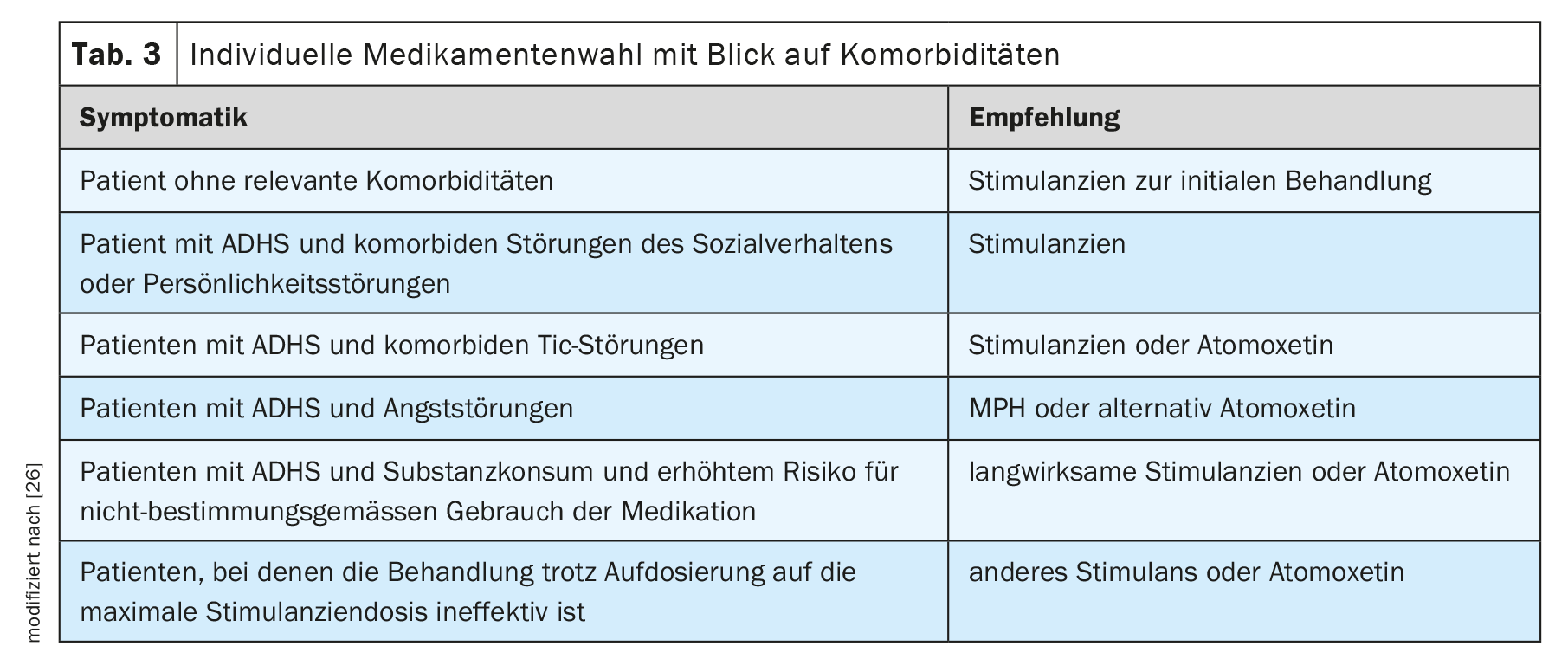

For a long time, there were no pharmacological treatment options approved for adults in many European countries. There are now at least three preparations available: the gold standard methylphenidate (MPH) and lisdexamphetamine (LDX) as stimulants and amotoxetine (ATX) as a non-stimulant. Which preparation is selected should be considered on an individual basis (Table 2, Table 3). According to the S3 guideline, in addition to the approval status and patient preferences, the desired duration of action and the expected efficacy profile also play a role [26].

According to studies, 75% of treated patients benefit from MPH therapy when a symptom reduction of at least 30% is used as a criterion for therapeutic success [27]. Several meta-analyses have demonstrated significant efficacy on core ADHD symptoms [28–31]. In addition, it leads to a reduction in emotional regulation disorder [31]. The stimulant inhibits the reuptake of dopamine and, to a lesser extent, noradrenaline from the synaptic cleft into the presynaptic neuron by inhibiting the corresponding monoamine transporters. This increases the transmitter concentration in the synaptic cleft and optimizes signal transmission.

The effect of LDX, on the other hand, is different. This prodrug is hydrolyzed into the active d-amphetamine in the cytosol of erythrocytes. D-amphetamine causes an increased release of dopamine and norepinephrine in the brain and inhibits their reuptake into the presynaptic neuron. In principle, the efficacy appears to be comparable to that of MPH with a slight tendency toward a higher effect size on core symptomatology .

The norepinephrine reuptake inhibitor atomoxetine inhibits the norepinephrine transporter. This increases the availability of norepinephrine in the synaptic cleft of the neuron. Its prescription is indicated primarily when stimulants are not effective or are not tolerated or rejected by the patient. However, the efficacy is lower than that of stimulants [34].

Long-term treatment necessary

In principle, the duration of drug treatment is based on the individual needs of the patient. Sometimes time-limited interventions may be appropriate, for example, when changes in life circumstances could lead to functional impairment. In general, however, the treatment should be set for the long term. Follow-up studies show that long-term therapy over several years leads to a greater reduction in symptoms and improvement in everyday functioning than short-term treatment [35]. Nevertheless, discontinuation attempts should always be planned in order to check the continued indication for pharmacotherapy.

Therapy management in the light of polypharmacy

Particularly in the treatment of adult ADHD in combination with other disorders, the question of potential interactions between the various active substances often arises due to polypharmacy. Since, as reported, depression is a particularly common comorbidity in ADHD, the parallel administration of stimulants and antidepressants is of great importance. However, the additional administration of antipsychotics or anticonvulsants is also common. In addition, internal medicines and self-medication preparations taken by patients can also play a role.

Treatment with uncoordinated medication can have serious consequences for those affected. In fact, 20-30% of all adverse drug reactions (ADRs) are caused by interactions. However, not all potential interactions are clinically relevant and most can be avoided. ADHD medications can also generally be combined well. Nevertheless, care should be taken to ensure that the drug used as a combination partner has a narrow therapeutic range. Clinically relevant mechanisms are the influence on bioavailability, changes in physiological structures, the inhibition or induction of CYP enzymes as well as transport mechanisms and pharmacodynamic interactions.

The CYP enzymes and transport proteins such as P-glycoprotein pumps are of particular importance, as together they form a barrier to protect the organism from foreign substances. An increase or loss of the effect can be caused by interactions with smoking, grapefruit juice or St. John’s wort, among other things. For this reason, strong inhibitors and inducers of the CYP enzymes and the P-glycoprotein, such as es-/citralopram, clarithomycin/erythromycin, metropolol, simvastatin or haloperidol should be avoided if possible [36–38].

Take-Home-Messages

- Around 80% of ADHD persists into adulthood.

- Only a small proportion of affected adults are diagnosed, as the symptoms change and comorbidities are often in the foreground.

- An effective treatment model is multimodal and includes psychoeducation, psychotherapy and pharmacotherapy.

- Psychostimulants are the first choice for pharmacological therapy.

- Treatment with MPH can improve both the core symptoms and the emotional dysregulation.

Literature:

- Nyberg E,et al: ADHD in adults. HOGREVE 2013.

- Fayyad J, et al: Br J Psychiatry 2007; 190: 402-409.

- Rösler M, et al: Nervenarzt 2008; 3: 320-327.

- Barbaresi WJ, et al: Pediatrics 2013; 131: 637-644.

- Rothenberger A and Neumärker KJ: Scientific history of ADHD. Steinkopff Verlag Darmstadt 2005.

- Kramer F, Pollnow H: About a hyperkinetic disorder in childhood. Monatsschr Psychiatr Neurol 1932; 82: 1-40.

- Chess S: Diagnosis and treatment of the hyperactive child. NY State J Med 1960; 60: 2379-2385.

- Wender PH: Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder in Adults Psychiatr Clin North Am. 1998; 21(4): 761-774.

- Wender PH, et al: Adults with ADHD. An overview. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2001; 931: 1-16.

- Polyzoi M, et al: Neuropsychiatr Dis Treat. 2018; 14: 1149-1161.

- Ströhlein B., et al: NeuroTransmitter 2016; 27.

- Chien WC et a. Res Dev Disabil 2017; 65: 57-73.

- Bron TI, et al: Accid Anal Prev 2018; 111: 338-344.

- Chang Z, et al: JAMA Psychiatry 2017; 74: 597-603.

- Barkely RA: Psychiatr Clin North Am 2004; 27(2): 233-260.

- Kittel-Schneider S, et al: J Clin Med 2019; 8(10): 1643.

- Krause J, Krause KH: ADHD in adulthood. Schattauer Publishers 2014.

- Rösler M, Retz W: Diagnosis, differential diagnosis and comorbid conditions of ADHD. Psychotherapy 2008; 13(2): 175-183.

- Pineiro-Dieguez B, et al: J Atten Disord 2016; 20: 1066-1075.

- Barkley RA: Attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder. A handbook for diagnosis and treatment, 3rd ed. Guilford, New York

- Chen Q, et al: PLoS one 2018; 13(9): e0204516.

- https://register.awmf.org/assets/guidelines/028-045k_S3_ADHS_

2018-06.pdf (last accessed on 16.01.2024). - Adler L, et al: Patterns of psychiatric comorbidity with attention deficit/hyperactivity disorder. Abstract 119.19th US Psychiatric & Mental Health Congress; November 2006; New Orleans, Louisiana.

- Rostain AL: Postgrad Med 2008, 120(3): 27-38.

- Torgersen T, et al: North J Psychiatry 2006; 60(1): 38-43.

- Association of the Scientific Medical Societies. S3 guideline: ADHD in childhood, adolescence and adulthood. Registration number 028-045. AWMF; 2017.

- Retz W, Rösler M. Therapy resistance in the treatment of ADHD in adulthood. In: Schmaus M, Messer T. Therapy resistance in mental illness. Munich: Elsevier; 2009: 175-188.

- Faraone SV, et al: J Clin Psychopharmacol 2004; 24: 24-29.

- Koesters M, et al: J Psychopharmacol 2009; 23: 733-744.

- Castells X, et al: CNS Drugs 2011; 25: 157-169.

- Retz W, et al: Exp Rev Neurother 2012; 12: 1241-1251.

- Mészáros A, et al: Int J Neuropsychopharmacol 2009; 12: 1137-1147.

- Stuhec M, Lukić P, Locatelli I. Ann Pharmacother 2018; 53: 121-133.

- Cortese S, et al: Lancet Psychiatry 2018; 5: 727-738.

- Fredriksen M, et al: Eur Neuropsychopharmacol 2013; 23: 508-527.

- Schoretsanitis G, et al: Clinically Significant Drug-Drug Interactions with Agents for Attention-Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder, CNS Drugs 2019; 33(12): 1201-1222.

- Ingelman-Sundberg M: Genetic polymorphisms of cytochrome P450 2D6 (CYP2D6): clinical consequences, evolutionary aspects and functional diversity. Pharmacogenomics J 2005; 5: 6-13.

- Müller F, Fromm MF: Transporter-mediated drug-drug interactions. Pharmacogenomics 2011; 12: 1017-1037.

InFo NEUROLOGY & PSYCHIATRY 2024; 22(1): 12-16