Available treatments for idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis (IPF) slow disease progression but do not improve symptoms or quality of life. Most patients with IPF report a cough associated with rapid disease progression. Evidence-based treatment options for cough in IPF are few and far between. A British study has now demonstrated for the first time a benefit of morphine in IPF-related cough.

There is a great unmet need for therapies that improve the quality of life of people with IPF and treat the very common and often disabling symptoms such as coughing. Research investigating the impact of cough burden on quality of life in IPF has shown the stability of this symptom over time. Lack of clarity about the pathogenic mechanisms causing cough in IPF limits therapeutic options for patients and physicians, write Dr. Zhe Wu of the National Heart and Lung Institute, Imperial College, London, and Royal Brompton and Harefield Hospitals, London, and his colleagues [1].

They conducted a prospective, multicenter, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled, two-way crossover study in three specialized centers in the United Kingdom. This study included patients aged 40 to 90 years with a diagnosis of IPF within the last five years and a self-reported persistent cough for at least eight weeks and a cough score on the visual analog scale (VAS, 0-100 mm) of 30 mm or more. Patients were randomly assigned (1:1) to twice-daily placebo or twice-daily oral controlled-release morphine at a dose of 5 mg for 14 days. This was followed by a seven-day washout phase before they were switched to the other treatment in a crossover. The order of morphine and placebo administration was randomized according to a computer-generated schedule. The primary endpoint was the frequency of coughing while awake, which was recorded on days 0 and 14.

The morphine was administered as an encapsulated tablet, and both morphine and the corresponding placebo capsule were colored the same to maintain masking. Patients, investigators, study nurses and pharmacy staff were masked prior to treatment allocation. In an emergency, masking could be lifted via the electronic database system (sealed envelope, EDC) if knowledge of the treatment was required for appropriate clinical management or participant welfare.

Morphine reduced cough frequency by at least 20%

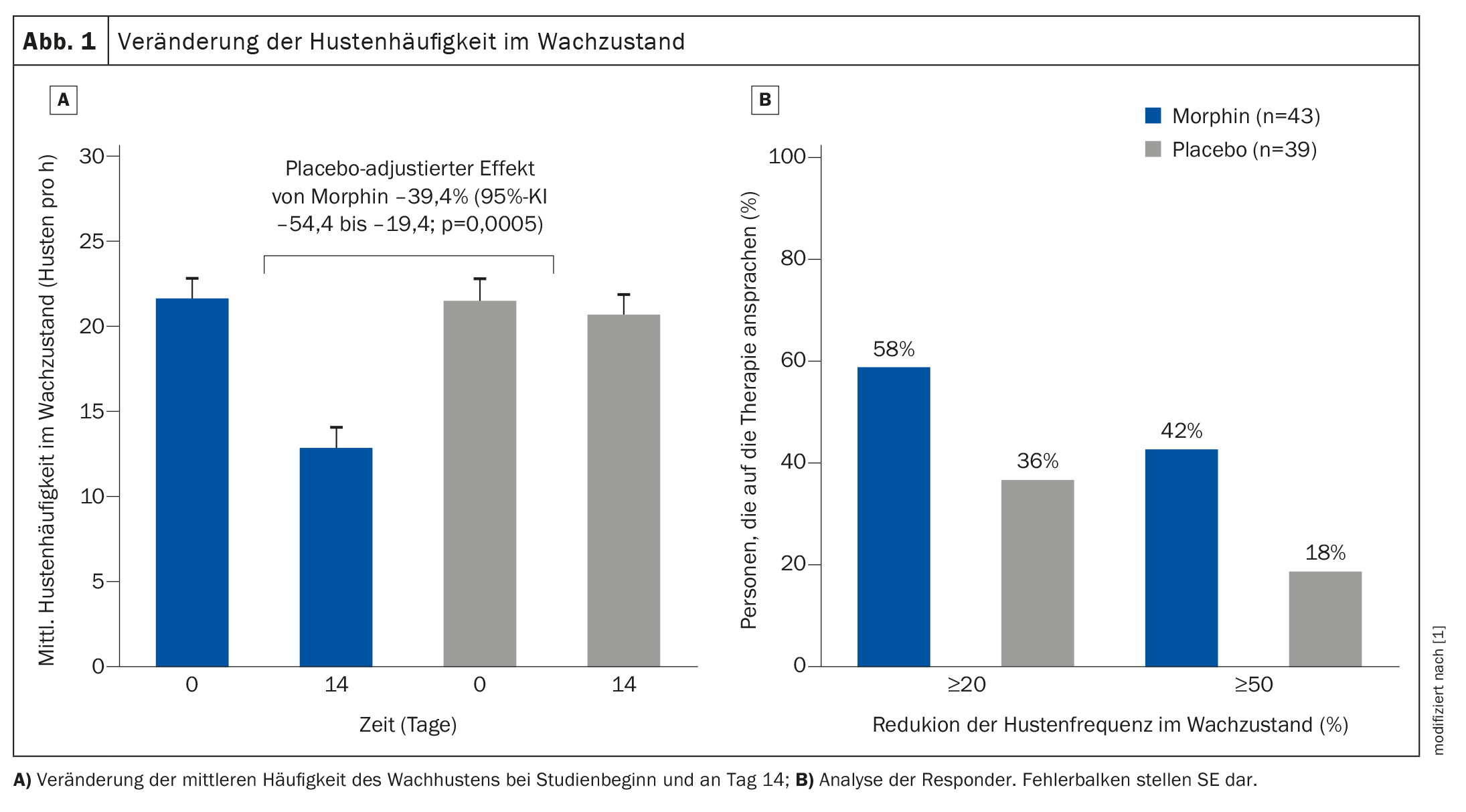

Of the 44 patients randomized, 43 completed the morphine treatment and 41 completed the placebo treatment. In the intention-to-treat analysis, morphine reduced the objective cough frequency during wakefulness by 39.4% (95% confidence interval (CI) –54.4 to –19.4; p=0.0005) compared to placebo (Fig. 1) . The average daily cough frequency decreased from 21.6 (SE 1.2) coughs per hour at baseline to 12.8 (SE 1.2) per hour with morphine, while cough rates per hour did not change with placebo (21.5; SE 1.2 vs. 20.6; SE 1.2). Quality of life (subjective assessment via questionnaire) and IPF symptoms also improved. Overall, treatment adherence was 98% in both the morphine and placebo groups. Adverse events were observed in 17 (40%) of 43 participants in the morphine group and in six (14%) of 42 patients in the placebo group. The main side effects of morphine were nausea (six [14%] out of 43 participants) and constipation (nine [21%] out of 43). One serious adverse event (death) occurred in the placebo group.

In summary, the researchers found that low-dose controlled-release morphine reduced daytime cough frequency by at least 20% in IPF patients with lung-related cough and improved the overall impression of cough change in more than half of the patients. The objective number of coughing attacks over a period of 14 days was also significantly reduced compared to placebo.

Concerns about side effects

The use of opioids in patients with chronic respiratory disease is often restricted due to concerns about side effects and the potential for addiction and abuse. In a recent study, extended-release nalbuphine, a dual-acting κ- or μ-opioid antagonist, reduced the incidence of chesty cough in people with IPF by 51.6%. However, almost a quarter of the participants discontinued treatment during the use of nalbuphine due to side effects. Further studies are required to determine a dose that maintains the clinical benefit with optimal tolerability.

In contrast, Dr. Zhe Wu and colleagues highlighted that in their study, only one participant discontinued treatment with low-dose controlled-release morphine and a lower proportion of participants experienced side effects than in the Nalbuphine study. The safety assessments carried out during the study visits were reassuring. In addition, the stability of scores on the Hospitality and Depression Scale and the L-IPF Symptom Energy Domain indicated that there were no morphine-induced mood changes or excessive fatigue, the authors write.

Treatment with low doses of controlled-release morphine significantly improved objective and subjective cough measurements in patients with IPF-related cough and showed promise as an effective antitussive drug in these patients. In view of the negative effects of coughing in IPF patients, these results support the short-term use of the drug in clinical practice, according to the authors. Future research should focus on long-term studies.

Literature:

- Wu Z, et al.: Morphine for treatment of cough in idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis (PACIFY COUGH): a prospective, multicentre, randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled, two-way crossover trial. Lancet Resp Med 2024; 12: 273–280; doi: 10.1016/S2213-2600(23)00432-0.

InFo PNEUMOLOGIE & ALLERGOLOGIE 2024; 6(2): 20–21