High blood pressure is the most common treatable risk factor for heart attack, stroke or kidney damage. If a patient is suspected of having secondary hypertension – i.e. a form of hypertension in which there is a specific and potentially reversible reason why the blood pressure is elevated – further diagnostic clarification is recommended. A common cause of secondary hypertension is the presence of sleep apnea syndrome. And the most common endocrinological cause is primary hyperaldosteronism (also known as Conn’s syndrome).

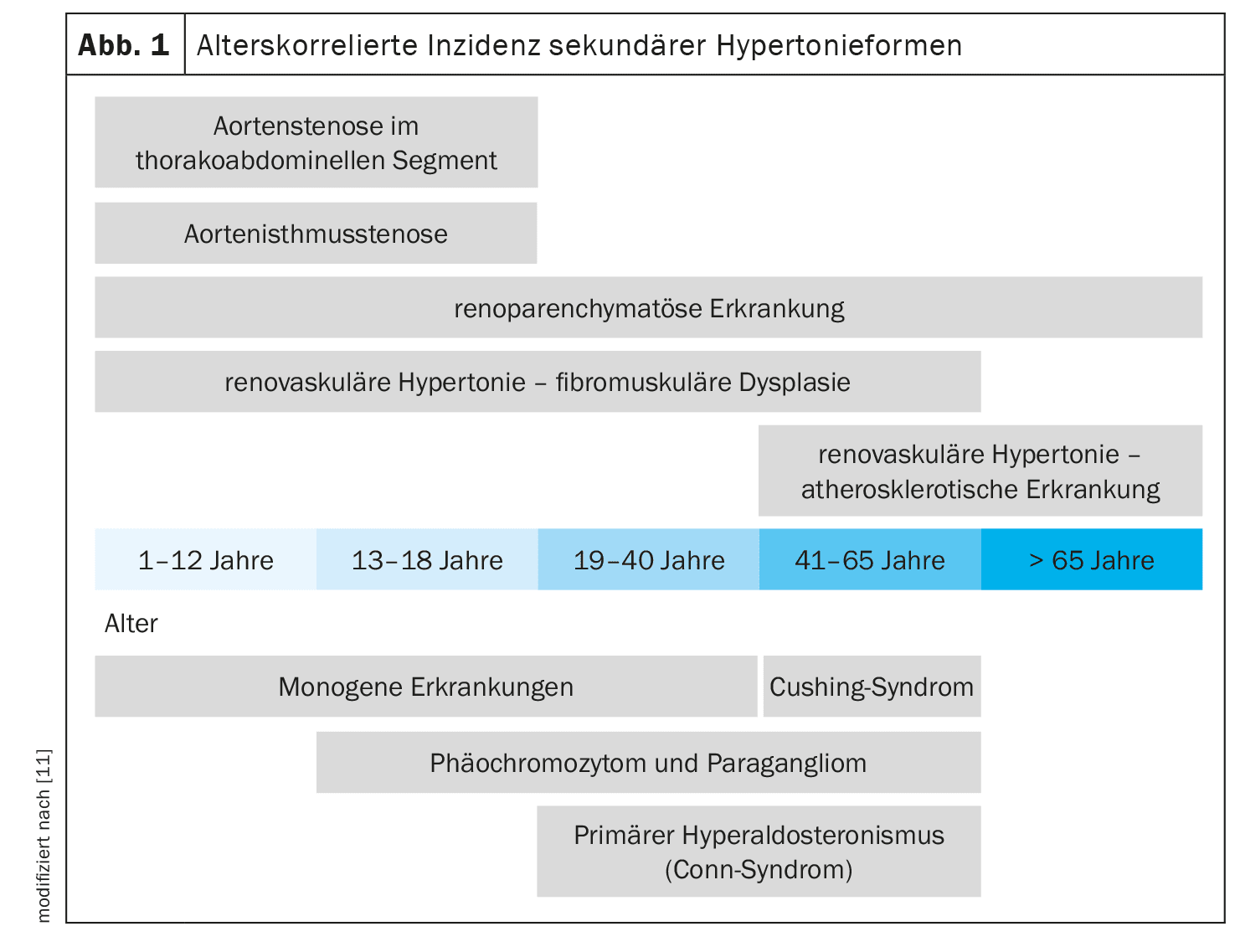

Hypertension is defined as treatment-resistant if the target blood pressure is not reached despite the use of three antihypertensive drugs in maximum tolerated doses (preferably RAS blocker, calcium channel blocker, thiazide-type diuretic) [1,2]. It can be assumed that around 1 in 10 hypertensive patients have a secondary form of hypertension [3]. Depending on the source or what is subsumed, the prevalence can be up to 20%. An age-correlated overview of the underlying diseases that can lead to secondary hypertension is shown in Figure 1. In addition to cases with, by definition, treatment-resistant hypertension or a rapid deterioration of a previously stable blood pressure, it is recommended that all patients with a first manifestation of hypertension at the age of <40 years should be investigated for possible underlying diseases. PD Dr. med. Thilo Burkard and PD Dr. med. Matthias Betz from the University Hospital Basel, presented two case examples from their clinical routine [3].

Case 1: OSAS

The first case study involved a 62-year-old patient who, despite taking an antihypertensive triple fixed combination** (amlodipine 5 mg, valsartan 80 mg, hydrochlorothiazide 12.5 mg) and a dual combination& of bisoprolol fumarate (5 mg) and hydrochlorothiazide (12.5 mg), repeatedly showed a blood pressure of 150/90 mm Hg during home measurements over a prolonged period [3]. The obese patient had a BMI of 42.5 kg/m2 and type 2 diabetes. The 24-hour blood pressure measurement revealed a lack of nocturnal dipping, which is an indication of possible sleep apnea. On the question of further diagnostic procedures, it was mentioned that the “Epworth Sleepiness Scale” questionnaire is often used in cases of suspected symptomatic sleep apnea, but that this is not very meaningful in patients with refractory hypertension [3]. A more suitable screening method in this context is nocturnal pulse oximetry. Put simply, a pulse oximeter measures the amount of oxygen in the blood. Oxygen saturation and breaths are measured via a sensor located in front of the nose. If more than 10 pauses in breathing lasting longer than 10 seconds are recorded per hour, an examination in a sleep laboratory is indicated [4]. Polysomnography is the “gold standard” for confirming or ruling out OSAS [5]. The sleep laboratory examination can be used to determine the number of breathing pauses per hour and night in relation to total sleep. If there are more than 10 breathing pauses per hour, treatment should be initiated [4]. In the present case, the sleep laboratory examination led to the diagnosis of severe complex sleep apnoea with a position-dependent obstructive or central component.

** 1-0-1

& 1-0-0

CPAP (Continuous Positive Airway Pressure) therapy was prescribed as a therapeutic measure; the patient was also referred to the obesity consultation with the aim of losing weight and was advised not to take sleeping pills [3]. A CPAP device consists of a basic device and a mask with a connecting tube for the air supply. Experience has shown that CPAP therapy usually works relatively well if the device is worn for at least 6 hours during the night [3]. This was also the case with this patient. In addition, he achieved a weight reduction from 126 kg to 96 kg and his BMI decreased from 42.5 kg/m2 to 32 kg/m2. In the course of the study, the 24-hour blood pressure measurement values improved significantly and a largely normal blood pressure profile with nocturnal dipping was observed.

| Hypertension and OSAS: evidence base There is a broad evidence base on the links between obstructive sleep apnea (OSAS) and arterial hypertension, particularly resistant hypertension [6]. In the Wisconsin Sleep Cohort Study, participants with severe OSAS (apnea-hypopnea index >15/h) had a 3.2-fold increased risk of developing hypertension [7]. The effects of CPAP therapy on arterial blood pressure were examined in a meta-analysis of 32 randomized studies in which “active hypertension therapy” (CPAP, protrusion splints, antihypertensives) was compared with a “passive group” (sham-CPAP, antihypertensives, weight loss). The results showed that CPAP therapy significantly reduced both systolic and diastolic blood pressure [8]. The fact that additional weight reduction is useful for sleep apnoea can be seen in a publication by Chirinos et al. [9]. |

Case 2: Conn’s syndrome

In a 46-year-old female patient (BMI 23.9 kg/m2) with known osteoporosis following primary hyperparathyroidism, a blood pressure of 160/100 mm Hg was measured in the doctor’s office [3]. Recently, similarly elevated values had also occurred several times during home measurements. According to the 24-hour blood pressure measurement, the patient had grade II hypertension with no nocturnal dipping. Hypokalemia was also detected. The suspected diagnosis was primary hyperaldosteronism (Conn syndrome).

| Conn’s syndrome: often overlooked In Conn’s syndrome, aldosterone has escaped the control of other hormones. Overproduction occurs and blood pressure rises. At the same time, the body loses potassium and the blood becomes alkaline. Alkalosis is a disorder of the acid-base balance in which the pH value of the blood rises to over 7.45. This is known as alkalosis. Together with a potassium deficiency and high blood pressure, it is part of the classic triad of Conn’s syndrome. In most cases, however, only the blood pressure is elevated. Conn’s syndrome is therefore often overlooked for a long time. On average, it takes around ten years from the first manifestation of high blood pressure to the confirmed diagnosis of Conn’s syndrome. |

| to [10] |

If patients have blood pressure values of >150/100 Hg in three independent measurements on different days of the week and an inadequate response to three antihypertensive drugs (including diuretics), it is recommended to test for the presence of primary hyperaldosteronism [3]. The first step is to determine the aldosterone/renin ratio. In primary hyperaldosteronism, aldosterone is high while renin is very low. It is best to measure in the morning, at least 2 hours after getting up (blood sample taken after 5-15 minutes of sitting). Spironolactone and eplenerone must be discontinued for four weeks before determining the aldosterone-renin ratio. Other interfering medications should also be discontinued if this is possible without major risks for the patient. After this “case finding”, a confirmatory test is required, except in patients with spontaneous hypokalemia, suppressed renin and aldosterone >550 pmol/l. The confirmatory test consists of an intravenous (i.v.) saline load test:

- Infusion of 1 l NaCl 0.9% over 4 h

- aldosterone, renin, cortisol and potassium are determined before and after the infusion

- Aldosterone <140 pmol/l: primary hyperaldosteronism is very unlikely

- Aldosterone >280 pmol/l: primary hyperaldosteronism is very likely

The third diagnostic step involves localization diagnostics.

In the present case, autonomous aldosterone secretion was confirmed in the NaCl load test [3]. Localization diagnostics with the NNV catheter revealed unilateral secretion. A unilateral adrenalectomy was performed. The patient’s blood pressure values normalized over the course of the procedure.

Congress: medArt Basel

Literature:

- “Hypertension”, national health care guideline, short version, version 1.0 AWMF register no. nvl-009, https://register.awmf.org,(last accessed 27.08.2024)

- Bakris GL: Hypertension, www.msdmanuals.com/de/profi/herz-kreislauf-krankheiten/hypertonie/hypertonie,(last accessed 27.08.2024).

- “Severe Hypertension”, Meet the Experts, MTE 103, PD Dr. med. Thilo Burkard, PD Dr. med. Matthias Betz, medArt, Basel, 17-21.06.24.

- “Schlafapnoe-Syndrom”, German Brain Foundation, https://hirnstiftung.org,(last accessed 27.08.2024).

- Swiss Respiratory Society: Diagnosis and care of patients with obstructive sleep apnea syndrome, www.pneumo.ch, (last accessed 27.08.2024)

- S3 guideline, Non-restorative sleep/sleep disorders, chapter “Sleep-related breathing disorders”, German Society for Sleep Research and Sleep Medicine (DGSM), https://register.awmf.org,(last accessed 27.08.2024).

- Peppard PE, et al: Prospective study of the association between sleep-disordered breathing and hypertension. NEJM 2000; 342: 1378-1384.

- Fava C, et al: Effect of CPAP on blood pressure in Patients with OSA/ Hypopnea – a systematic review and metaanalysis. Chest 2014; 145(4): 762-771.

- Chirinos JA, et al: CPAP, weight loss, or both for obstructive sleep apnea. N Engl J Med 2014; 370(24): 2265-2275.

- “Conn syndrome: Curable high blood pressure is often only recognized late”, German Society for Endocrinology (DGE), 29.09.2021.

- Mancia G, et al: 2023 ESH Guidelines for the management of arterial hypertension The Task Force for the management of arterial hypertension of the European Society of Hypertension: Endorsed by the International Society of Hypertension (ISH) and the European Renal Association (ERA). J Hypertens 2023; 41(12): 1874-2071.

HAUSARZT PRAXIS 2024; 19(9): 42-43 (published on 18.9.24, ahead of print)