Hepatic encephalopathy encompasses a wide spectrum of nonspecific symptoms. Most often, infectious diseases are responsible for an episode. Lactulose or lactitol is used for treatment. In severe cases, therapy is supplemented with rifaximin.

Hepatic encephalopathy (HE) often occurs as a complication of advanced chronic liver disease, less commonly in the setting of acute liver failure. Like the first appearance of ascites or a first variceal hemorrhage, it marks the transition to the phase of decompensated cirrhosis. In HE, decreased liver function and/or portosystemic shunts lead to impaired brain function by allowing neurotoxic degradation products, including ammonia, to enter the brain directly from the gut. Portosystemic shunts are bypass circuits (e.g., esophageal varices, splenorenal shunts, etc.) between the portal vein inflow area and the systemic venous circulation as a result of liver cirrhosis with portal hypertension or extrahepatic portal vein thrombosis in an otherwise healthy liver. Rarely, they already occur congenitally.

Clinical presentation and diagnosis of hepatic encephalopathy.

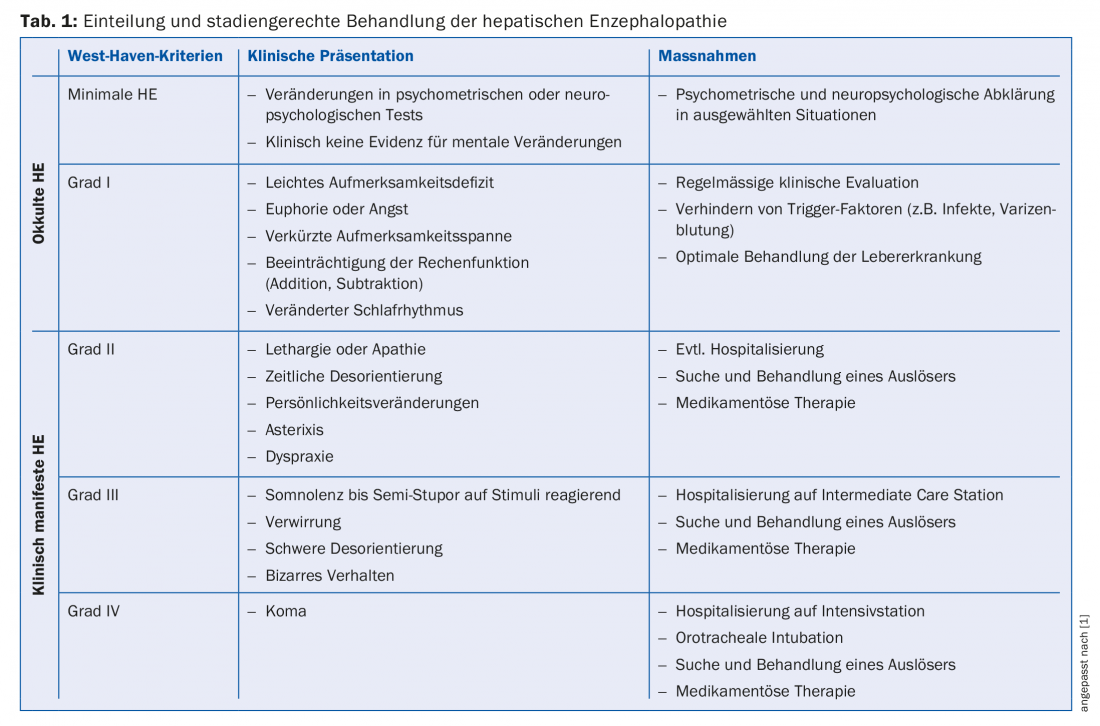

Clinically, HE presents with a wide spectrum of nonspecific neurological and psychiatric symptoms that can range from discrete behavioral abnormalities to coma. The severity of HE is classified according to the West Haven criteria (Tab.1). In contrast to early subtle neuropsychological changes, typical asterixis (“flapping tremor”), a coarse tremor of the hands, or an episode of disorientation are easily and reliably recognized as symptoms of HE in clinical practice and are taken as the first signs of clinically manifest HE [1].

10-14% of patients with (compensated) cirrhosis develop clinically manifest HE during the course of their disease, which is often very disabling for the patient – and especially for their relatives. For early detection, it makes sense to regularly look for indications of HE in the consultation with the patient (sleep, concentration or orientation disorders, emotional fluctuations), his relatives (personality changes, behavioral abnormalities or orientation disorder) and in the clinical examination (asterixis). Asterixis can best be tested by having the patient extend the arms and flex the hands dorsally with fingers spread. To diagnose minimal or occult HE, experienced investigators can perform a battery of neuropsychological or psychometric tests (e.g., Portosystemic Encephalopathy Syndrome Test, Critical Flicker Frequency Test, Inhibitory Control Test, Stroop Test) [2]. These examinations may be useful in selected situations – for example, in patients with severe fatigue without clinical signs of HE or in patients in whom minimal HE would already have a relevant impact on work activities or public safety.

Conversely, HE must be considered in any patient with known liver disease and new-onset neurologic or psychiatric changes. The diagnosis of HE is made clinically, in the absence of confirmatory ancillary investigations. According to the clinical presentation, the possible differential diagnoses (intracranial hemorrhage, cerebrovascular insult, cerebral infection, metabolic disorder, or drug-toxic causes) must be carefully excluded. The level of ammonia in the blood correlates insufficiently with the severity of the clinic and provides no diagnostic or prognostic benefit. On the other hand, if the ammonia level is normal, the diagnosis of HE must be doubted and a differential diagnosis must be searched for all the more intensively.

Management of hepatic encephalopathy.

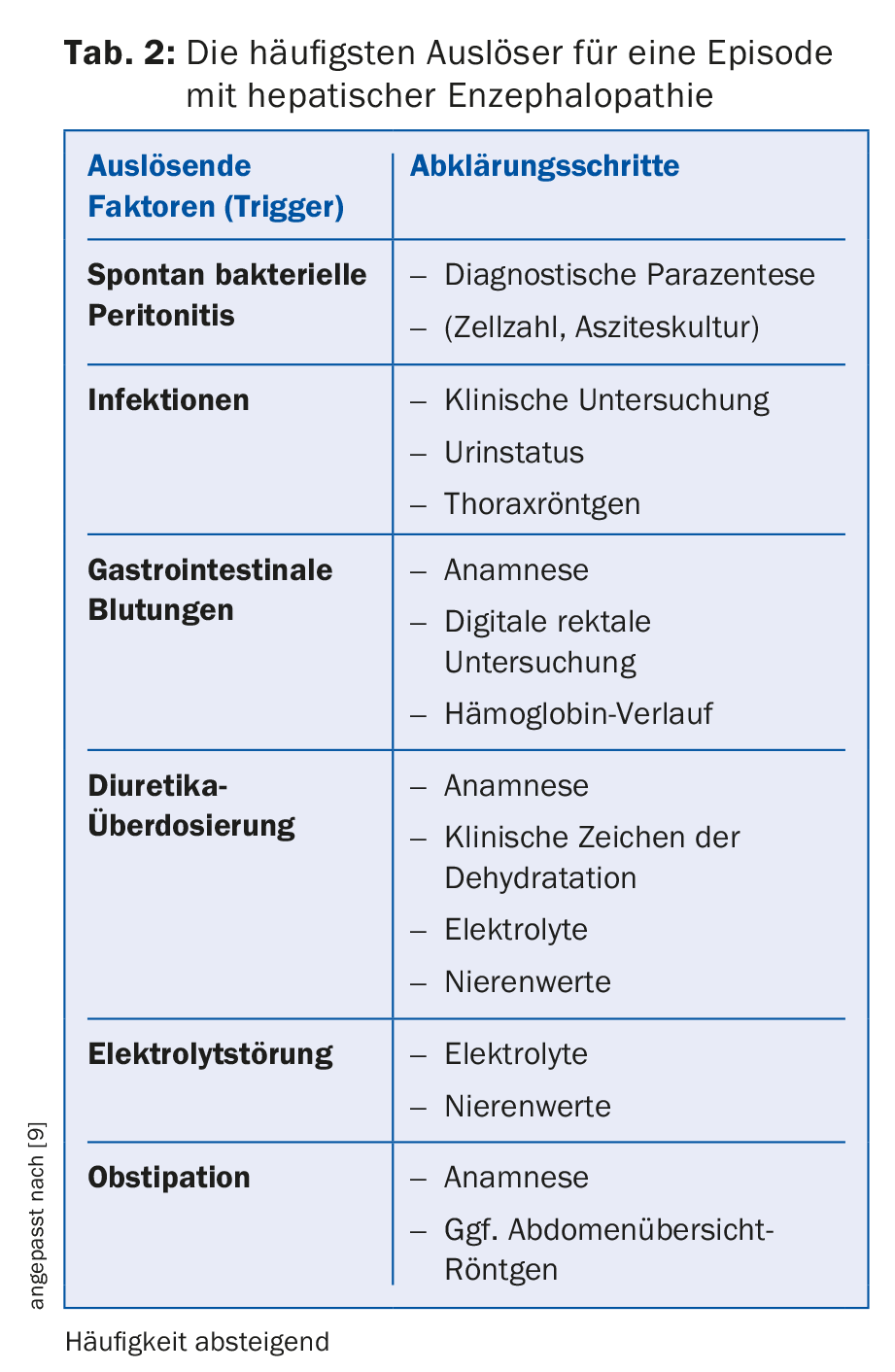

Triggering factors, first and foremost infections, are often responsible for deterioration of liver function and development of hepatic encephalopathy (Tab. 2) . Therefore, a detailed history, clinical examination, and laboratory tests are necessary to clarify an episode with clinically manifest HE. The most common focus of infection is spontaneous bacterial peritonitis; therefore, diagnostic paracentesis in the patient with ascites is an important part of the workup. It is probably more practical for the primary care physician to refer the patient with clinically manifest HE to the nearest emergency department or specialist for the elaborate work-up. The patient must be hospitalized at the latest in the event of quantitative disturbance of consciousness (somnolence, stupor, coma) or disorientation. During the initial evaluation, it is critical to quickly identify a potential trigger and target treatment (e.g., ceftriaxone for spontaneous bacterial peritonitis, endoscopic hemostasis, etc.). The sole treatment of a triggering factor usually already brings an improvement in HE.

Disaccharides (e.g., lactulose, lactitol) are primarily used for drug therapy of a first episode with HE [3]. In addition to the laxative effect, disaccharides, by acidifying the colonic environment, favor bacterial strains that produce less ammonia and reduce intestinal absorption of ammonia. The initial daily dose of three to four times 20 g of lactulose (e.g., 30 ml Duphalac®) or three to four times 10 g of lactitol (e.g., 10 ml Importal®) is continuously adjusted with the goal that the patient will settle two to three soft stools daily [4]. It should be noted that in addition to lack of treatment adherence, overdose with lactulose is a common reason for a recurrent episode with HE [5]. After an episode has passed, permanent therapy with lactulose is continued for prophylaxis.

For the treatment of severe episodes or for prophylaxis after episodes of HE that occurred during therapy with lactulose, lactulose therapy can be successfully combined with rifaximin (e.g., Xifaxan® 550 mg 2×/d), a nonabsorbable antibiotic [6]. In selected cases, the standard therapy described (lactulose and rifaximin) can be supplemented by branched-chain amino acids (e.g., Hepa-Merz® granules) [7].

Crucial for a good outcome after an episode with HE is – contrary to conventional wisdom – a sufficiently high calorie and protein diet with 35-40 kcal resp. 1.2-1.5 g protein per kg body weight daily [8]. For patients with recurrent episodes, the possibility of liver transplantation should be evaluated by the appropriate specialists at the transplant center.

Take-Home Messages

- Hepatic encephalopathy is a common complication of liver cirrhosis.

- The clinical presentation of hepatic encephalopathy includes a wide spectrum of nonspecific neurologic and psychiatric symptoms.

- In most cases, precipitating factors (most commonly spontaneous bacterial peritonitis or other infectious diseases) are responsible for an episode of hepatic encephalopathy. They need to be treated in a targeted manner.

- Lactulose or Lactitol is used to treat a first episode of hepatic encephalopathy and also a recurrent episode. In severe cases or episodes that have occurred despite therapy with lactulose, therapy with lactulose is supplemented with rifaximin.

Literature:

- Vilstrup H, et al: Hepatic encephalopathy in chronic liver disease: 2014 Practice Guideline by the American Association for the Study Of Liver Diseases and the European Association for the Study of the Liver. Hepatology 2014; 60(2): 715-735.

- Rahimi RS, et al: Hepatic encephalopathy: how to test and treat. Curr Opin Gastroenterol 2014; 30(3): 265-271.

- Als-Nielsen B, et al: Non-absorbable disaccharides for hepatic encephalopathy: systematic review of randomised trials. BMJ 2004; 328(7447): 1046.

- Schumann C: Medical, nutritional and technological properties of lactulose. An update. Eur J Nutr 2002; 41(Suppl 1): 17-25.

- Bajaj JS, et al: Predictors of the recurrence of hepatic encephalopathy in lactulose-treated patients. Aliment Pharmacol Ther 2010; 31(9): 1012-1017.

- Patidar KR, et al: Antibiotics for the treatment of hepatic encephalopathy. Metab Brain Dis 2013; 28(2): 307-312.

- Gluud LL, et al: Branched-chain amino acids for people with hepatic encephalopathy. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2015; (9): CD001939.

- Amodio P, et al: The nutritional management of hepatic encephalopathy in patients with cirrhosis: International society for hepatic encephalopathy and nitrogen metabolism consensus. Hepatology 2013; 58(1): 325-336.

- Brunner F, Dufour J, De Gottardi A: Therapy and prevention of hepatic encephalopathy. Switzerland Med Forum 2014; 14(27-28): 523-525.

HAUSARZT PRAXIS 2017; 12(12): 27-30