Acute loss of visual acuity is a leading symptom in ophthalmology, which can also be diagnostically groundbreaking in other areas of medicine. For the patient, acute vision impairment is always an event that is perceived as particularly threatening. It is important to quickly and reliably establish differential diagnoses and to start a therapeutic regime that both prevents further reductions in visual function (e.g., in the fellow eye) and, if necessary, helps avoid life-threatening consequences. This article is intended to provide an overview of possible aids in diagnosis and therapy for patients with acute visual loss.

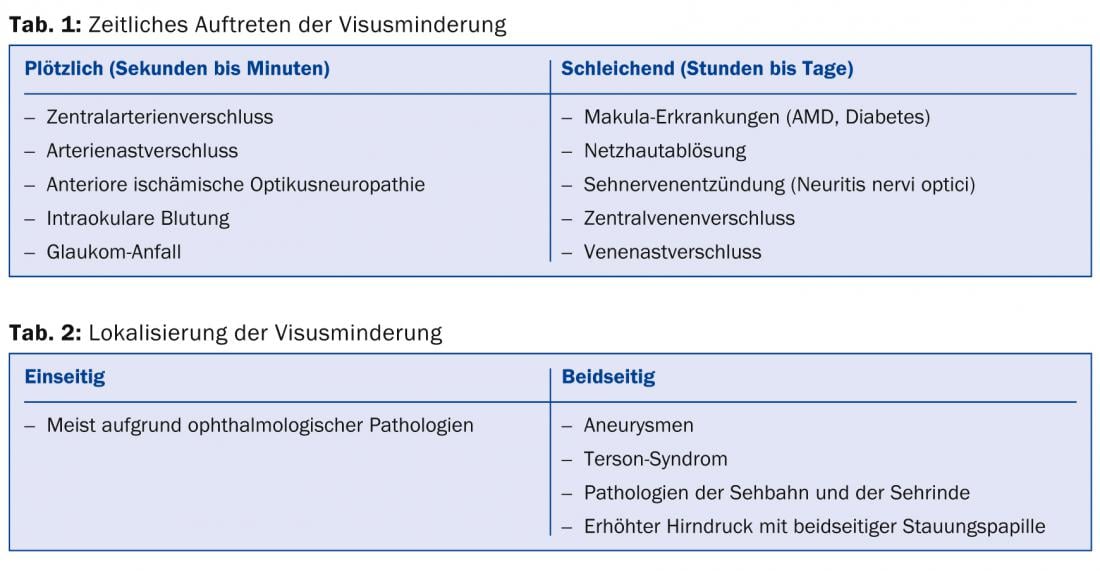

At the beginning of each examination is the extensive, but also targeted ophthalmological and general anamnesis. Duration and localization of visual deterioration as well as other limitations of visual function such as double vision, visual field loss and reduction of color vision help in diagnosis (Tables 1 and 2).

The assessment of the severity of vision loss is done by means of visual acuity testing: visual acuity with the best possible correction (i.e., with spectacle correction or with contact lenses, for example) for distance and near should be tested individually for each eye. Under certain circumstances, a banal incipient presbyopia (presbyopia) can already be detected here if the visual complaints are only indicated at close range. If, on the other hand, the patient squints his eyes, undercorrected myopia may be inferred.

Basic neuroophthalmologic examinations include the swinging-flashlight test to rule out unilateral optic nerve affection (relative afferent pupillary deficit). Visual field defects can be detected by finger perimetry. Strabologic pathologies are detected by the cover/uncover test, and ocular muscle paresis is detected by motility testing in the nine directions of gaze.

A (hand-held) slit lamp is required for examination of the anterior segment of the eye, and an ophthalmoscope for the posterior segment. This allows the detection of pathologies such as erosio corneae as well as papilledema.

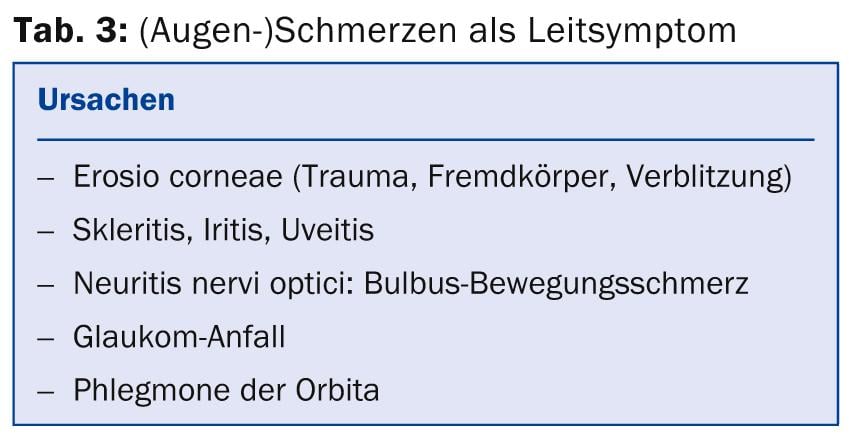

Concomitant ocular pain can further narrow down the diagnosis: it is indicative of organic damage to the eye, but headache can also be indicative, for example, of intracranial pressure problems or aneurysms (Tab. 3).

The following is a list of the typical conditions that can most commonly result in unilateral or bilateral visual acuity reduction.

Central Artery Occlusion (CAD)

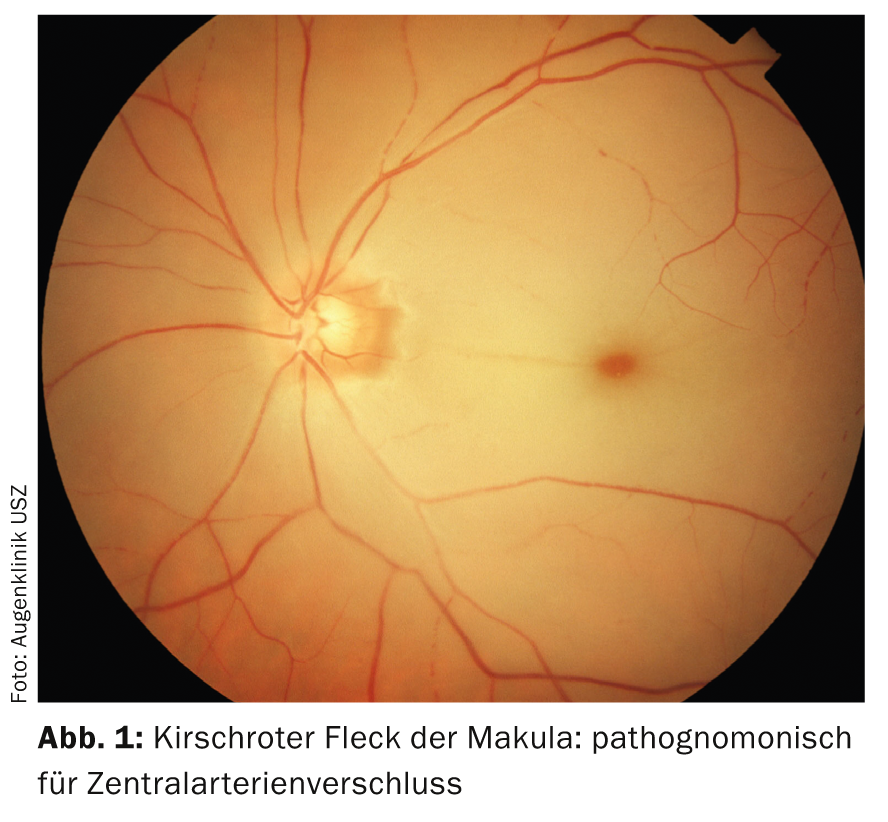

In central retinal artery occlusion (CAD), the visual loss is so acute that the patient can often give an exact time of the event. There are classically no other symptoms, so ZAV is also described as acute, painless, and unilateral blindness. Funduscopically, the pathognomonic “cherry-red spot” of the macula impresses: The retinal center with the clearly visible choriocapillaris demarcates itself from the surrounding edematous-white and inferiorly perfused retina (Fig. 1).

In case of incomplete occlusion, only one branch of the central artery (so-called branch artery occlusion) may develop with retinal edema in the respective stromal area. The extent of visual acuity reduction then depends on the involvement of the macula.

The cause is often embolism, e.g. from carotid stenosis. The value of a possible lysis therapy is very controversial and is now usually no longer performed, especially since the period of irreversible retinal damage (30 minutes to a maximum of a few hours) until the start of therapy is usually already exceeded. Initially, attempts can be made to deliver the central embolus further into the retinal periphery by lowering intraocular pressure; this can be achieved by anterior chamber puncture using paracentesis or by administration of systemic carbonic anhydrase inhibitors (acetazolamide, Diamox®).

Rapid clarification of possible causes is important: In addition to vascular and cardiac examinations (carotid Doppler, cardiac echo, etc.), this includes standard general medical examinations.

A special form of the clinical picture is the “amaurosis fugax” symptomatology: Here, the patient regains full visual function within a short time (seconds to minutes) due to spontaneous dissolution of the embolus. Since such an event may, of course, be followed by complete embolization, the same diagnostic as therapeutic considerations should be made.

Retinal vein occlusion

The loss of visual acuity in venous occlusions, unlike arterial occlusions, is of a less acute dynamic; often manifesting over hours to days. Funduscopically, congested and tortuous veins as well as patchy and striated hemorrhages over the entire posterior pole are apparent (Fig. 2).

Venous occlusions may also involve parts (branch retinal vein occlusion, VAV) or the entire retina (central retinal vein occlusion, ZVV).

Risk factors in younger patients include oral contraceptives, obesity, and nicotine abuse.

Visual prognosis also depends, among other factors, on whether an ischemic or non-ischemic form of CVC is present. The distinction can be made by fluorescence angiography, which is a standard diagnostic tool in the larger eye centers. In the prognostically worse, ischemic form, panretinal laser treatment is indicated.

Swelling in the area of the macula (macular edema) is amenable to therapy by intravitreal injections with anti-VEGF preparations or steroid implants, possibly in combination with focal laser coagulation.

Systemic therapies by hemodilution are usually not (no longer) performed.

Anterior ischemic optic neuropathy (AION)

As with ZAV, the visual loss in anterior ischemic optic neuropathy (AION) is painless, acute, and unilateral. The affected eye shows a relative afferent pupillary deficit (RAPD), and optic disc swelling can be detected by ophthalmoscope. It is crucial in this clinical picture to think of the differential diagnosis of giant cell arteritis (Horton’s disease). The typical complaints of the patient such as new headaches, chewing pain, fatigue, fever, weight loss, hypersensitivity of the scalp, and a hardened and pressure-dolent temporal artery (Fig. 3) are indicative.

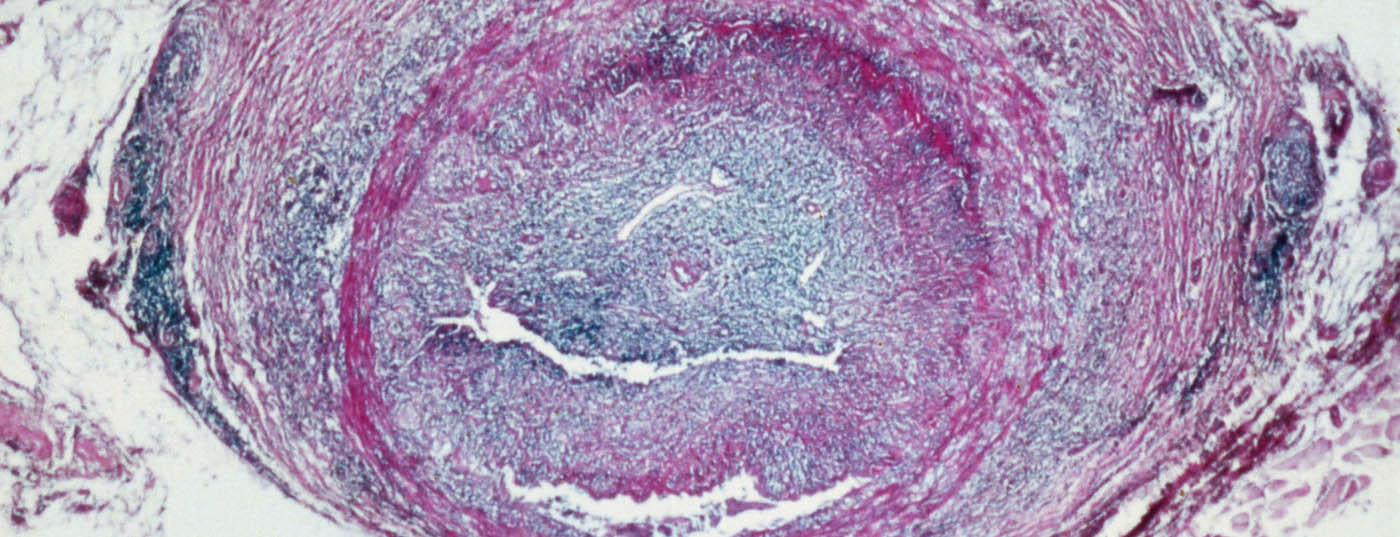

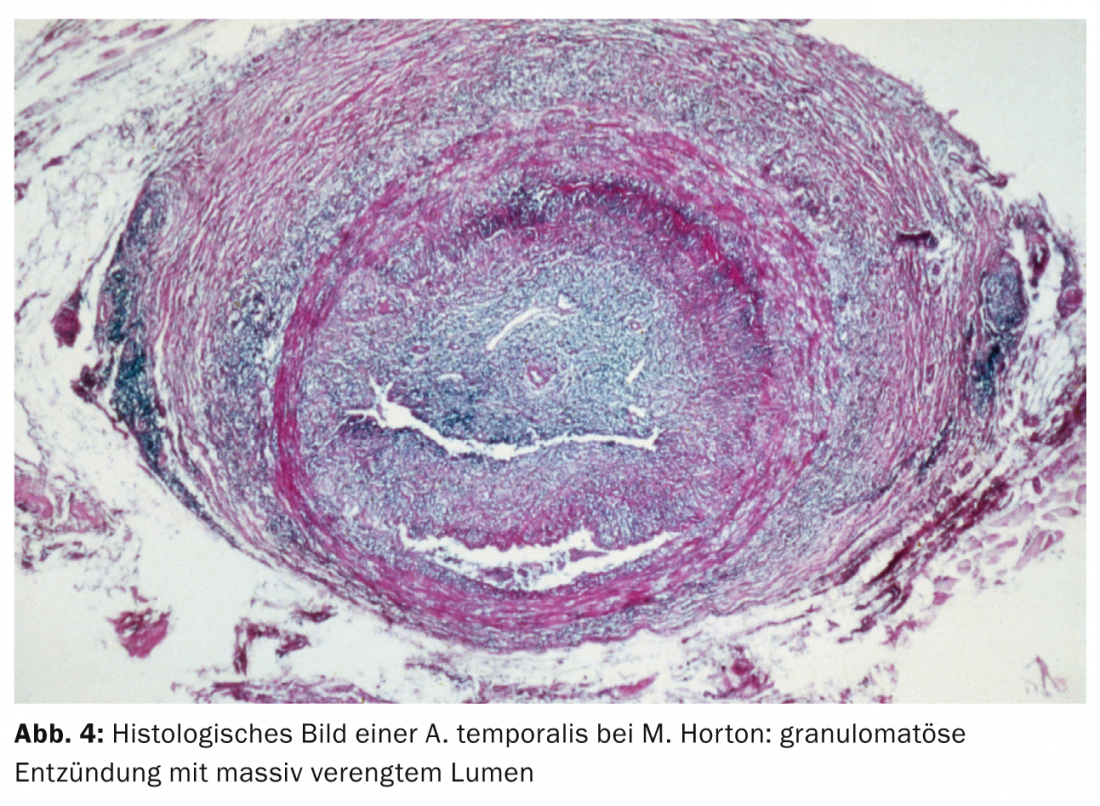

The mean age at onset is 75 years, and women are two to three times more likely to be affected. Laboratory chemistry reveals an increased erythrocyte sedimentation rate and elevated inflammatory parameters (CRP). To prevent visual acuity reduction in the fellow eye, immediate high-dose systemic cortisone therapy must be initiated (e.g., 4× 250 mg methylprednisolone [Solumedrol®] i.v. for three days, followed by 1.5-2 mg/kgKG prednisone p.o.). To confirm the diagnosis, a biopsy of the temporal artery should be performed within seven to ten days: Histology shows granulomatous inflammation of the tunica media with massive narrowing of the vascular lumen (Fig. 4).

After resolution of symptoms and normalization of inflammatory parameters, a cautious reduction in steroid treatment can be made, but usually not in the first four weeks after initiation of i.v. therapy; weekly reductions should not be greater than 10% of the initial dose. Attention should be paid to the development or worsening of osteoporosis. Regular ophthalmologic check-ups should be weekly initially and monthly thereafter. Overall, systemic therapy may be necessary for months to years, and the dose is strictly based on the inflammatory parameters and the patient’s symptoms.

Neuritis nervi optici (NNO)

In neuritis nervi optici (NNO), the period of visual loss is variable and can range from days to weeks. The typical movement pain of the affected eye and the RAPD are indicative. Typically, all ocular segments are unremarkable, and pathology in the optic disc region is rarely found; this has led to the adage “the patient sees nothing, the doctor sees nothing.” Mostly young women are affected, a neurological clarification with the question of MS-typical lesions (demyelinating foci in the white matter) in the MRI and if necessary a cerebrospinal fluid puncture should be performed promptly. Since many NNOs heal without further consequences as well as without any therapy, the suspected diagnosis of multiple sclerosis should only be made by the attending neurologist in justified cases, also for psychological considerations. High-dose systemic steroid therapy should be undertaken only when MRI demonstrates two or more plaques typical of MS and there are no contraindications.

Retinal detachment (Amotio retinae)

Typical symptoms of retinal detachment are sooty vision, seeing a curtain (from above) or a wall (from below), which first lead to a limitation of the peripheral visual field. The most common form is rhegmatogenous amotio, in which tears occur in the area of attachment sites of the vitreous with the retina.

Pain or external changes of the eye are not found. If the retinal detachment progresses towards the macula, there is an additional relative scotoma in the area of the detached retina and thus also a reduction in central visual acuity. Prognostically, involvement of the central retina is unfavorable.

Therapeutically, various surgical techniques can be used. The goal of all procedures, whether denting from the outside by means of a plug or from the inside by means of vitrectomy, is the reattachment of the retina to the retinal pigment epithelium.

Age-related macular degeneration (AMD)

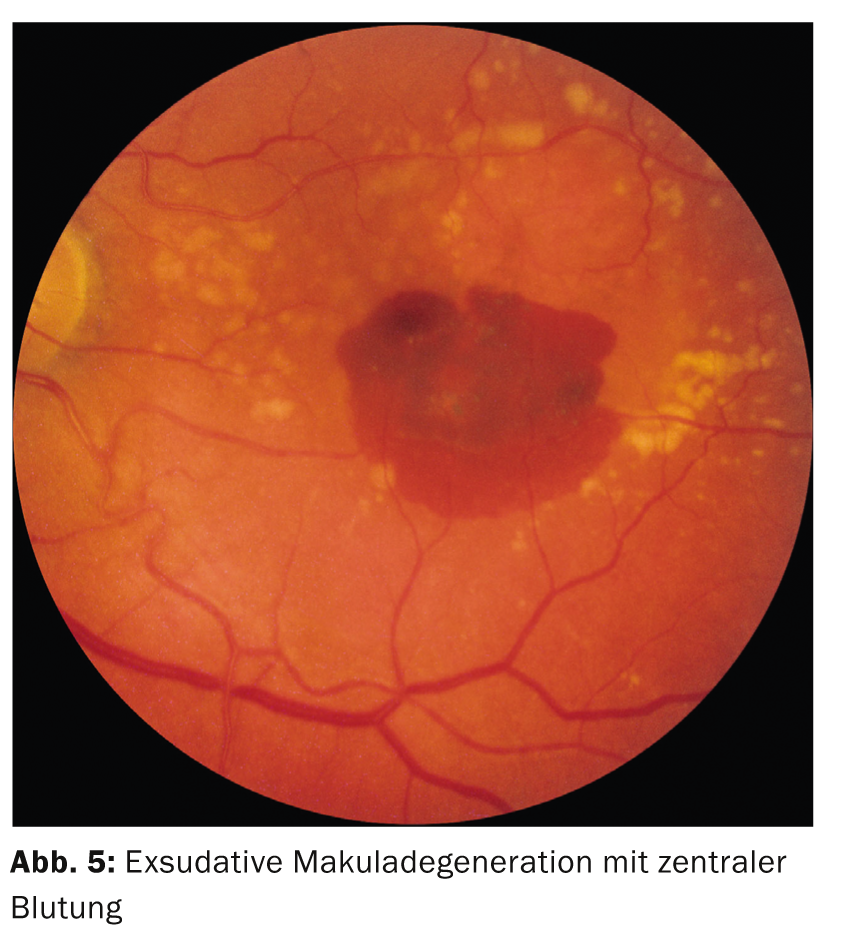

Age-related macular degeneration (AMD) is the most common cause of blindness in the Western world. The reduction in visual acuity is usually gradual, but it can also be acute if a hemorrhage occurs in the center of the retina as part of the disease (Fig. 5).

The visual loss of the exudative (“wet”) form is more marked and progresses more rapidly than that of the nonexudative (“dry”) form. As an additional symptom, the so-called “Amsler test” can be used: On a squared paper, the patient indicates the straight lines as crooked. This is caused by edema in the center of the retina.

The therapy of the dry form is difficult, here dietary supplements (“eye vitamins”; lutein preparations) are currently recommended. In the treatment of the wet form, anti-VEGF drugs have become established, which are injected into the vitreous (Lucentis® [Ranibizumab] and Eylea® [Aflibercept]).

Traumatic injuries of the cornea: Erosio, foreign body, keratitis.

Any disturbance in the integrity of the corneal epithelium leads to the typical symptoms such as pain, foreign body sensation, epiphora (trickling of tears) and, depending on the location of the lesion, also to acute visual loss. In most cases, minor injuries such as fingernail trauma, branches, paper edges, etc. lead to erosio corneae. The defect can be quickly demarcated by fluorescein staining and a blue light lamp. (Fig. 6).

To rule out a foreign body, both upper and lower eyelids should be ectropionated. Therapy consists of humidifying eye drops and/or ointments and local antibiotic shielding. If the cause of the accident is unclear or the redness or inflammation of the eye persists, referral to an ophthalmologist is advisable. To properly treat more serious inflammation caused by germs such as fungi or acanthamoebae, an ophthalmologic evaluation is mandatory for contact lens wearers.

Johannes P. Eisenack, MD

CONCLUSION FOR PRACTICE

- A thorough history of the type, duration, and location of visual loss provides clues to the etiology of the disease.

- Simple diagnostic tools can further narrow down the etiology.

- In the case of sudden painless blindness, the further focus for clarification lies in the internal or neurological area.

- In case of directly recognizable affection of the eyes, a rapid ophthalmological clarification should be performed.

HAUSARZT PRAXIS 2014; 9(7): 34-38